Our Top Reads of 2014

Our team's picks for our best features of 2014.

Towards the end, Boy C asked to read a statement had prepared. It was probably the longest and most controlled speech he’d ever given, even as he trembled and focused on his handwritten refill. He was sorry for everything he’d done. He’d never had a girlfriend, or a friend, and he just wanted to keep being talked to and keep being included. He said he could try to explain how as the medication wore off he stopped thinking of consequences and just acted on impulse, but that he knew it wasn’t an excuse. He said he just wanted to stay, that he would even do some days at home to avoid trouble. He wanted to finish NCEA Level 1 and then find a course somewhere. He just wanted one last chance.

Three Boys looks at how schools fail many of our neediest students through expulsion processes weighted in favour of the smart, rich or able. It does so in a way that’s both powerful, and profoundly sad. In giving voice to the boys that broke the rules, Joe adds heartbreaking colour and depth to decisions often dismissed as black and white. The boys’ stories show the tragic outcomes that result when tightly-drawn lines of authority can’t deal properly with the tangled mess of human behaviour.

It’s easy to write colour without adding anything. The phrase I hate the most is ‘as she sips a cup of tea’ or something - that just drives me nuts. When people are interviewed in cafés, they always describe the coffee like it says something about the character. They have to be telling details and they have to say something about the person.

Gavin Bertram's interview series with the feature writers shaping the future of print journalism was rigorous and illuminating, covering everything from their process ("I need an opening scene to know where I'm going") to the hazards of the job ("I'm banned from ever being on air or on the premises at bFM") to the act of writing itself ("torturous"). Read them here: Duncan Greive, Naomi Arnold, Ben Stanley, Beck Eleven and Charles Anderson.

Start Your Own Fucking Band: An Oral History of The Mint Chicks

We were never trying to piss anyone off. We were just making music for people to enjoy.

They say it’s better to burn out than fade away. The Mint Chicks blazed a little while before exploding in a fist fight and a semi-famous screamed sentence: “Start your own fucking band”. Kieran’s oral history, and Louis and Frances’ accompanying video, tracks the band’s journey from early days to final cataclysm, investigating the creativity, combustibility and youthful confidence that made them great.

A Brief History of Silo Theatre

It was a January morning and he was standing in the carpark of what is now the Basement – what was then the Silo – with a member of its trust board, Frances McCahon. She handed him the keys, looked at the venue, and gave him a single piece of advice: “Don’t fuck it up.”

Shane Bosher took over a down-and-out theatre company in its so-called “dark ages” and turned it into one of the most important creative outlets in Auckland. He did so while refusing to shy away from the edgy, the difficult, the dark and the complicated. Rosabel's brief history of Silo is an insight into the method of a man who managed to not only not fuck it up, but flourish.

“I don’t believe in God,” Western Barbie said, and I always had a lot of respect for her point of view. Barbie was made in a factory. The small of her back was embossed with a copyright logo and the message: “Mattel Inc.” Barbie had met her maker, and she told me there had been nothing religious about it.

The towering stacks of the Huntly coal station, a bypassed and deserted Main Street, transubstantiation, and a young girl’s false plastic idol that won’t have a bar of it. Megan Dunn’s account of the six months of childhood where she retreated to the Waikato under her mother’s wing. The diorama she sets these figurines in is alternately vivid, stark, warm, haunting; what seals the deal is their return, 25 years later, for portraits and tearooms.

Eschatology and the Perpetual Music Apocalypse

So classical music’s prestige is everything: if it suffers the slightest chink in its reputation as valuable and necessary cultural capital upon which civilization depends, it loses its privilege to demand vast sums of public, private and corporate money. Cultural saviour rhetoric is a sales pitch in disguise. Brilliant youth orchestras out of the slums of Caracas and Soweto are held up as shining beacons illuminating exactly how classical music is ‘for’ everyone: it’s ‘good for’ everyone. This young boy has been saved from poverty and destitution because he now can play a Mozart concerto breathtakingly well! [Sure, he still doesn’t have clean drinking water, but through our music he can transcend this hardship.]

‘Classical music died when the first maestro said, “classics not dead”.’ Defined continually by its existential threats, classical music has become defined in the language of saviours and degeneration, reincarnations and doomed ends of the family line. But what music wasn’t having to act as a load-bearing shorthand for centuries of influence – what would we make and appreciate if Beethoven was erased from history tomorrow? Here, Celeste Oram dismantles her chosen target with clinical precision, but also no shortage of imagination and love.

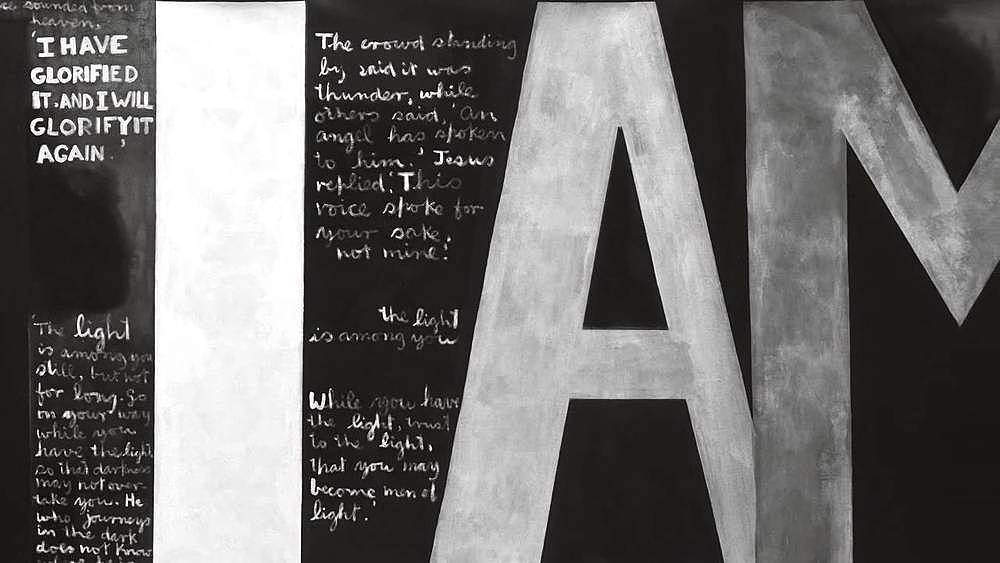

The Walters Prize: This Year, Art is the Winner on the Day

All the works have in part been enabled by non-artists: families and professionals are allowing public invasion of home, or suffering the artist’s absence from home, or suffering art wank invasion of their beloved newspaper. I like that the works are in the real world, that they comment on real-world stuff: poverty, privilege, power. Money. I like their politics. I like that they challenge the art world. I am suspicious that the Walters Prize, accurately described as a bourgeois phenomenon, has come up with a host of strong, radical works. Is it allowed because art doesn’t actually change anything? Are our galleries full of pet paper tigers?

Self-hailed as the country's toughest contemporary art competition, last year's Walters Prize show was its strongest one yet, but it was also its least visible one since only one of the finalists had a physical presence (in the traditional sense) at the Gallery. Janet McAllister's incisive rundown of the four finalists is insightful, witty and utterly essential.

Hanging Onto the Edge of the World

When people move to the coast, they are actively seeking isolation. There are hundreds of people along this stretch of coast that we haven't spoken to, and some of them speak with nobody at all. This is a community that lives without the compulsion to document, a physical existence that functions so directly in response to the elements that it resists reflection. But in its little hollow in the hills, Barrytown has a unique sense of togetherness fostered or forced through geographic constraints, played out often (though not exclusively) between the four salmon pink walls of the Barrytown Settler's Hall.

Nestled between the stark and sheer mountainside and the chopping, churning sea is the small settlement of Barrytown, a blip on the South Island's West Coast. Only a few hundred people live here, yet over the years, their iconic community hall has seen performances by Fugazi, The White Stripes, Busta Rhymes and Townes van Zandt. Last year, Claire Duncan and Jenna Todd travelled down to the town to meet the locals, and Claire's resulting story is one of the most elegant and poetic pieces of writing we've published on the site.

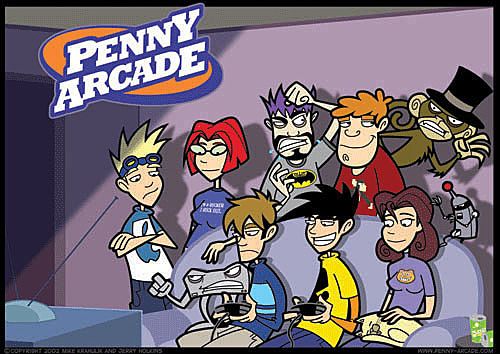

Bringing Up Bully: Penny Arcade and Growing Up On The Internet

I was enough of an idiot kid at the time to find this kind of daring high-concept stuff hilarious, despite growing up the only male in a house full of women. These were hardly unique sentiments - you can find similar punchlines today in the cesspools of 4chan, Reddit and Something Awful - but Holkins’ expansive vocabulary lent the whole thing a veneer of wit that proved fatal to sixteen-year-old boys with literary pretensions: the more obscene and vulgar something was, the funnier you were for saying it.

In April, Rory MacKinnon’s interrogation of webcomic Penny Arcade’s responses to accusations of perpetuating rape culture came well ahead of the #Gamergate furore that beset the tail end of 2014, but his article anticipated many of the issues subsequently raised. At heart though, his meditation on the way internet culture’s moved past ‘revenge of the nerds’-era payback politics and into a new phase of mainstream accessibility and sensibility (and the failure of certain artists to adapt) spoke to a lot of us whose formative years were spent online.

The Father Land: States of Becoming in the Writings of Martin Edmond

I still wanted to do the interview, but no longer for me - for my father. And I knew what I would ask him first. It would be that same first question that Martin Edmond had asked his own father, recorded on to a tape reel, and then transcribed into his first book of prose. A question that seemed straight forward enough when I first read it. What is the earliest thing that you remember?

Martin Edmond remains the most famous contemporary NZ writer to remain a virtual unknown. He’s received a Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement, plenty of nominations besides, but his association with the slippery genre of creative non-fiction and tangles with the palimpsest ghosts of psychogeography somehow place him before, outside, and ahead of his audience’s time. Simon Comber’s mammoth close reading of his work is commendable in itself, but the parallel journey he takes with his own father is this essay’s bloodflow.

The Vision Does Not Stop Here: The Factory’s International Dream

Kila Kokonut Krew, whose motto is “From the Pacific we Rise” was founded in a “garage in Manurewa” by Vela, Anapela Polataivo, Stacey Leilua, Aleni Tufuga and Glen Jackson, all of whom are involved in The Factory project. If the company’s initials seem provocative, it is no accident; KKK was founded in frustration and anger. Vela had auditioned four times before finally being accepted into Toi Whakaari, the NZ Drama School. But after graduating he found there were few opportunities for a Polynesian actor. The indignation in his voice is apparent, as he explains how he felt: “You’re telling me I’ve paid my fees in the National School of Drama and now I’m on my own? If I knew that I’d be a lawyer, I’d have changed to something else, instead of this creative dream.”

James Wenley’s feature on Vela Manusaute, Kila Kokonut Krew, and the first Pasifika musical observes and studies The Factory’s process as much as the end product, making it a valuable supp text to anyone who saw it in Manukau, Australia or Edinburgh last year. He traces the show’s profoundly public workshopping, the sacrifices cast and crew make on the expansive project, and the journey to carve out a new space in NZ’s once lily-white theatre scene.

Do Newspaper Columnists Dream of Electric Sheep?

I got postcards from train museums saying, ‘Thank you for taking us somewhere interesting every fortnight.’ People called reception at the Ministry of Education and asked to talk to me about economics. I got recognised on the Interislander as, ‘The bloke in the paper.’ My fans liked Michael Bublé and parsnips. They had holiday homes and let their fingers do the walking. They were nice people, but I was not one of them.

In describing the tension between his livelihood as a print columnist and his interests as a human being, Craig Cliff’s article on his two-year stint writing forYour Weekend is eminently relatable. It served as a timely reminder that like people, writing comes in an overabundance of forms and figures – and just because we’ve got some experience in one type doesn’t mean we’re going to enjoy doing all the rest.

If you're angry, depressed or dejected: join a political party. Get involved in the grass roots. Agitate for what you want it to stand for and how you think it should be run.

Election 2014 was brimming with outrage and anxiety; hopped up on a heady brew of WhaleOil, Kim Dotcom, hackers and venal politicians. When nearly half of all voters responded to its unbelievable drama with a collective ‘meh’ and a vote for more of the same, the left could easily have imploded in a paroxysm of righteous indignation. Hayden’s short feature is notable as a reaction that’s not reactionary. Written in the immediate aftermath of what was for him an extremely disappointing result, its call for cooler heads and tangible action is clear, realistic and surprisingly hopeful.