Tōku Tinana, Ōku Tikanga: My Body, My Rules

Me aroha ki te hā o Hine-ahu-one: Pay heed to the mana of women.

Content warning: this essay contains themes that some may find harmful, including sexual assault. Please use discretion when reading it.

I trust you to wash away the white stains, they are so hard to get out. I have been trying for years but that shit is potent. It stains us wāhine and when we walk past each other there's a sombre nod of recognition. I see you sister, we have seen the same shit that we have seen since Hine-nui-te-Pō left for the underworld. Then Māui became a white man with a white god. Then he became Ethan, Jack, and Eric for me. Who is he for you?”

Excerpt from ‘Matua’, by Anna McAllister

It was my 16th birthday when someone first used my body without my permission. Unfortunately, that would not be the last time. It happened again at a house party on the night of my final hand-in for my Bachelor of Fine Arts. This isn’t counting the hundreds of times I have been grabbed or touched without my permission. As a young art student, I would often use my art to unpack the traumas I had collected over the years. To try to heal from them. Naturally, art school became my safe place. Or rather, I created for myself a safe space within the white walls of an art school. I was always hyper-aware of the racism I, and others, faced within the institution, and even though it was my space of self-discovery, it still presented many challenges. My ability to make space for myself came through during my Master of Fine Arts – after I had regained some confidence in my ability to take up space.

As a survivor of sexual assault, I took up space by using my body, by taking back my autonomy. My body is intersectional. I am a fat, Indigenous wahine. I am aware of the fetishisation that is often put over my body, and yet I believe that embracing my body, whether through art, or social media, is a political act. An act of decolonisation. I show my nude body regularly. Instagram, in particular, has become an outlet for me to take up space and take back autonomy. Though anyone can see my Instagram, I know that it’s normally a certain type of person who engages with it – and they are on the body-sovereignty waka. Engari, every so often I will have people who are not on the waka, but because I have control over my Instagram, I can just block them.

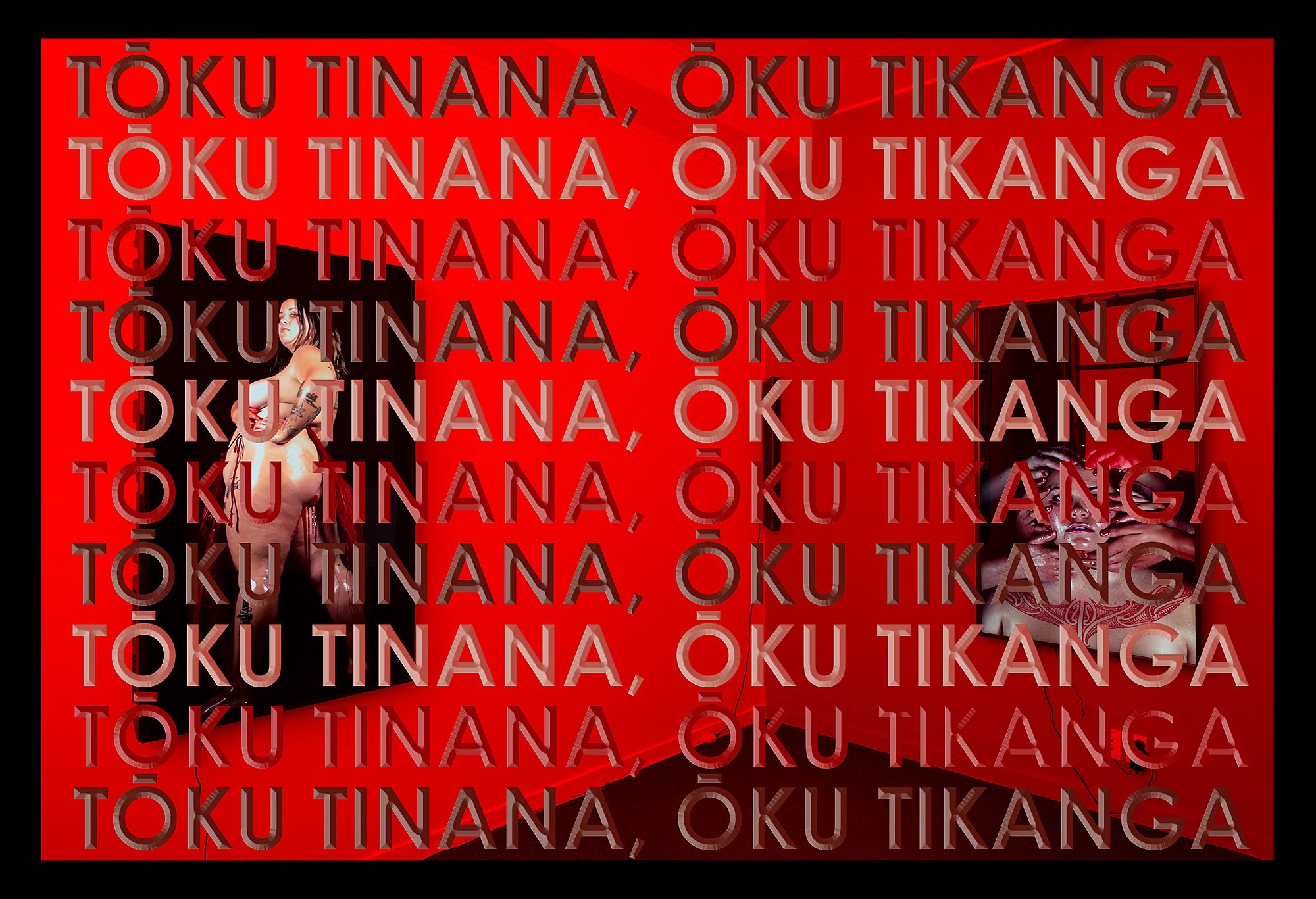

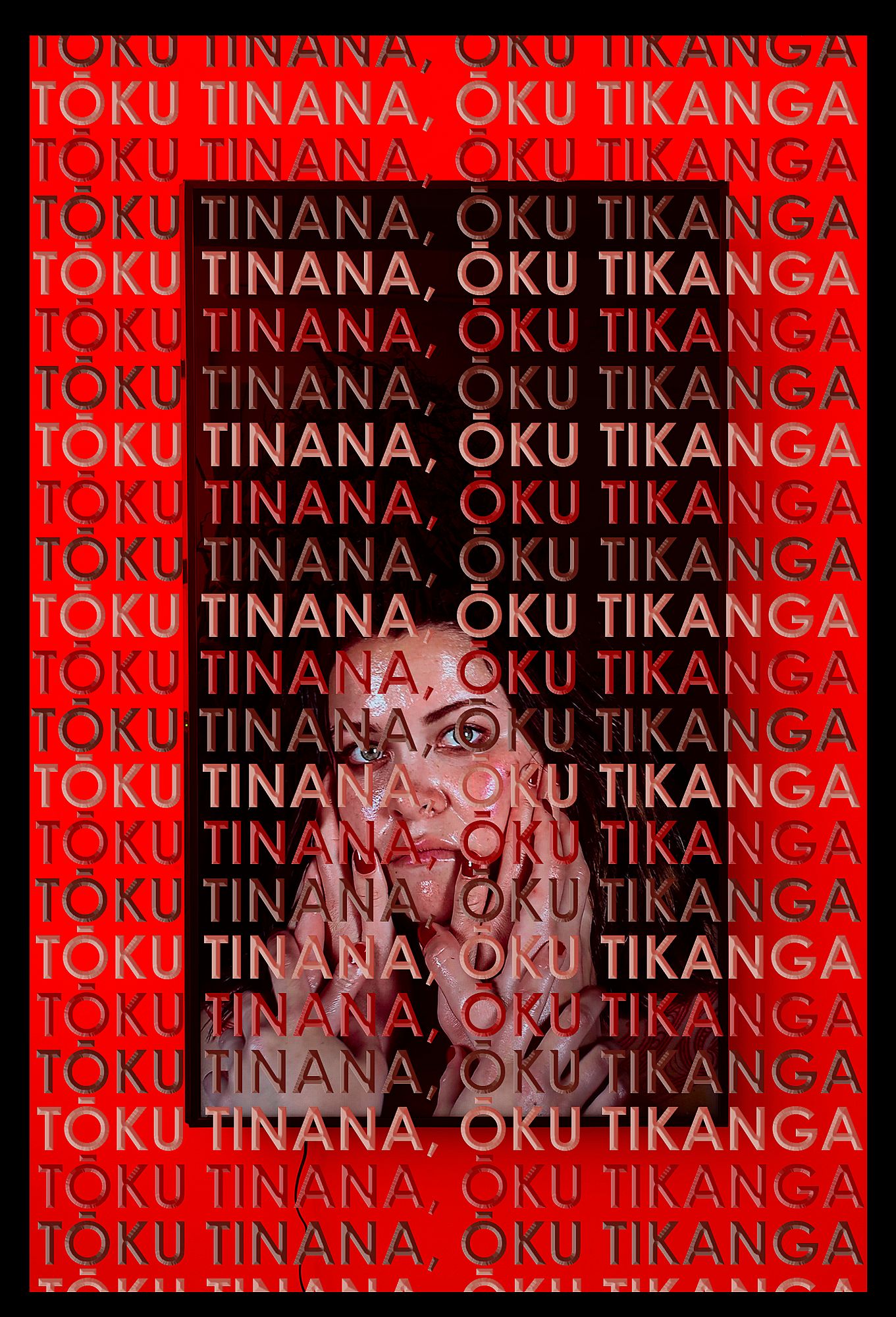

Images via @nope.thank.u.very.much (Instagram)

At the end of my master’s programme, my final work was an installation called Te Awa Atua, which consisted of a warm red room and three videos representative of Te Whare Tangata. One of these showed me full-length nude with blood dripping down my legs. The installation was in a separate room to the rest of the exhibition, which I shared with another incredible Māori artist, Maddi Walker. Both Maddi and I felt it was essential our work be in a safe and unmistakably Māori space. So that is what we created, using tikanga, tapu and noa to ensure that the mauri of our art was protected. When finished, this work represented the power of menstruation and the power of wāhine. It was an incredibly fulfilling work to produce. It was a culmination of eight years of learning, decolonising and reclaiming. And although I left art school very much exhausted, I was always in love with this work.

There are a few images of Te Awa Atua, one of which I used for an article called ‘The Angry Brown Woman: My Issue With Art Schools’. This article was a critique of the ‘liberal’ art school – a description of my time at university and the nature of the colonial institution. It was published both here on The Pantograph Punch, and on The Spinoff. I felt good sharing my image on these platforms, as I knew how it was being used and I trusted both these publishers to look after it and me, the same way I had done with the physical work.

Fast forward seven months, and I am on a popular art networking website, The Big Idea, and to my shock, I see my naked body front and centre. Confused, I click on the article to find that my body has been used in a PR piece about my former university. More specifically, to promote the very master’s programme I had completed. At first I laugh, thinking how ironic it is that they have used my image after I wrote an article calling out their racist behaviours. Then I cry. I cry because my body, my beautiful, fat, Māori body, has been taken from me, and used by the very people who knew that it had been used before. Due to the nature of my practice, the course coordinators quoted in the article are aware of my history as a sexual assault survivor and the intracate relationship I have with my work. The article says that “The programme honours obligations under Te Tiriti; the teaching is culturally aware.” The irony of this statement seemed lost on the university when they wrote this while colonising my body. I can’t help but wonder if this act is a power play, something to remind me that, even though I could write an article about my time there, they still own my mahi, my mauri, my tinana.

.

I vaguely remember signing a document a lecturer handed me, saying that the university reserves the right to use anything produced by students during their time at the institution. Though they do not own the Intellectual Property, they have unlimited rights to use it. This means that the university has the right to use anything created by students during their time at the university and this is by no means limited to the university where I studied; many have assumed ownership over IP that is unethical. I know of amazing Māori artists who have made hand-carved and amazing taonga that are, technically, owned by the university.

How can universities possibly claim to be Te Tiriti leaders, or even Te Tiriti aligned, when they are taking ownership of Māori IP, and in my case, Māori bodies? Surely their efforts to be woke are nothing more than a tokenistic façade. This IP issue is yet another layer that perhaps reveals true intentions.

Somewhat separate from the institutional discussion is the personal one. Those who allowed this picture to be used performed an act of ownership over my body – and they should have known better. I have kind of come to terms with the fact that my body, and my mahi, will likely continue to be used without my permission. That this is just a part of my life that I have to deal with. But what if I didn’t have to? What if universities honoured their students by seeking active consent throughout their interactions with them? If lecturers actually put their duty of care ahead of everything else, if they and the institution saw my art, and my body, with the mana and mauri it has? Then they wouldn't have used it in this way.

Tōku tinana, ōku tikanga.

My body, my rules.

.

Feature images: Ana McAllister, Te Awa Atua, 2019.