Toi moko in Toi Art: A Harbinger for a Conversation

Repatriation researcher, Amber Aranui, considers the inclusion of Toi moko in the exhibitions in Te Papa's Toi Art gallery.

Repatriation researcher, Amber Aranui, considers the inclusion of Toi moko in the exhibitions in Te Papa's Toi Art gallery.

Toi moko have been located on every continent in the world, and in the most unlikely of places, such as the islands of Guernsey and Mauritius. Walking through Te Papa’s Toi Art gallery, I was struck by the number of Toi moko (Māori preserved tattooed heads) present throughout the gallery space and, initially, I was taken aback. From previous internal discussions, I knew they would be there but I was unaware of how many, and in what form, these people from the past would confront me. I have since decided that their presence is a tohu, a harbinger, for myself and others to talk about them, their history, their trade, and their more recent travels home.

This is the first time, at least in the last 10 years that I have worked at Te Papa, that an exhibition has provided a platform for this type of discussion to take place. In my time here I have researched and experienced various aspects of the lives and deaths of people like those represented in Toi Art. My role, as the Researcher for the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme, has placed me in a unique position, one which enables me to share what I have learned, help right the wrongs of the past, and most importantly, participate in returning hundreds of ancestral remains back to their whenua and their people.

My role...enables me to...participate in returning hundreds of ancestral remains back to their whenua and their people.

Within Toi Art there are many stories and experiences to take in but for me, three separate, yet connected, exhibitions made an impact: Détour by Michael Parekowhai, situated in the Threshold Gallery on Level Four; Francis Upritchard’s untitled Pākēha head; the works of Shane Cotton, accompanied by Gordon Horatio Robley’s works on paper, both related to moko, which are located in the Retake gallery within the Tūrangawaewae: Art and New Zealand exhibition on Level Five.

My first time in Toi Art was as one of five taonga pūoro players, our role being to initiate the blessing of the space and to support the tohunga as they moved through the galleries reciting karakia, preparing the space and taonga for the public. This is standard practice here at Te Papa and on this instance was carried out with mana whenua from Te Ātiawa and Ngāti Toarangatira, as well as representatives from Whanganui, and the iwi-in-residence Rongowhakaata. It was here that I came face to face with the work of Francis Upritchard.

This strange, human-like head, perched on a stand in a case against the wall, recalled images I had seen of the heads of tūpuna displayed in museums throughout the world, including here in Aotearoa. I read the label with interest as it noted that it was part of a series of “so-called Pākehā shrunken heads.” Not again with this description of heads being “shrunken.” This is a common, but incorrect, description. The misconception conflates Toi moko with heads from South America made by the Jivaroan peoples of the Amazon regions, such as the Shuar. The practice of shrinking heads, known as tsantsa by the Shuar, is unique to that part of this part of the world. Essentially, the process involves the flesh being removed from the skull and placed over a small round object, such as a wooden ball or the skull of a monkey, before being boiled in a herbal infusion. This is not a process that Māori used. Toi moko are dried and preserved in a variety of ways – processes which have been recorded in detail and can be found in literature elsewhere.

The presence of Upritchard’s ‘Pākehā’ head and its accompanying, yet incorrect, interpretation acts as a prompt for dialogue on the trade of Toi moko, and I appreciate this. Its inclusion suggests that the trade of human remains is not an issue that should only be discussed among Māori, all New Zealanders should be educated about it, specifically as Pākēha heads were known to have been traded during the first half of the 19th century. The most well-known example of a traded Pākehā head is John (Joe) Rowe, who was said to be Te Rauparaha’s Pākēha.1 Rowe ran a store on Kāpiti Island where, among other things, he sold the preserved heads of Māori.2 The story goes that one day a group from Ngāti Tūwharetoa were visiting the island from Taupō, saw heads in Rowe’s shop and recognised two Toi moko as their whanaunga.3 Mourning their loss, the men requested the return of the two rangatira. Rowe is said to have laughed at their tears, refusing to return their whanaunga. From that moment, revenge was set. During a trading expedition to Whanganui in 1831, Rowe was killed and his head “cut off, dried and retained.”4 In a twist of fate, Rowe went from a trader of heads to a traded head. This was not the only story relating to the trade or creation of Pākehā preserved heads.

Pākēha heads were known to have been traded during the first half of the 19th century

In 2000, the late musician, Dalvanius Prime, travelled to Tasmania to repatriate the preserved head of a Pākehā steamship operator (who was apparently related to Prime) from the Whanganui River, who had been killed and traded. The head was eventually reinterred in a private ceremony up the Whanganui River.5 Prime was also involved in the return of Toi moko, work that was begun by Sir Graham Latimer in 1988 when he prevented the sale of a Toi moko from the Bonhams Auction House in London. This was followed closely by the work of Māui Pomare in his capacity as Chair of the New Zealand Museum Council in the 1990s.

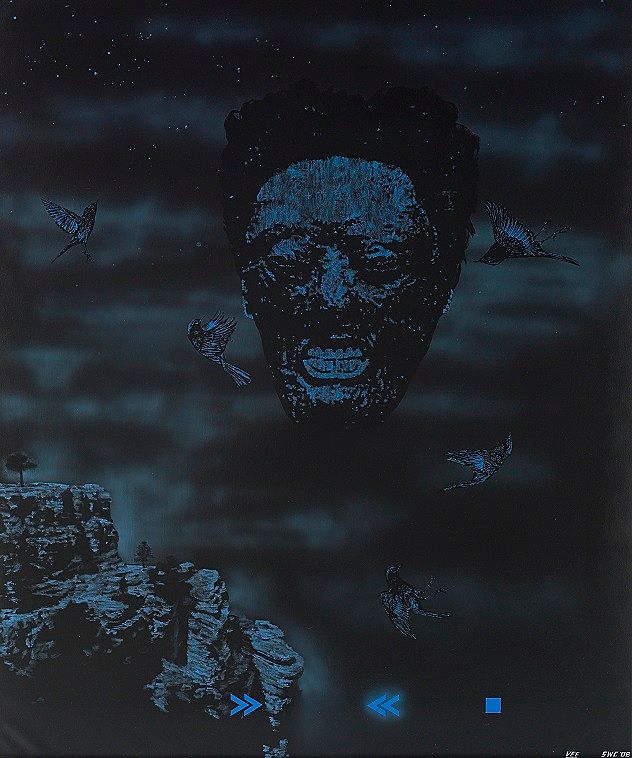

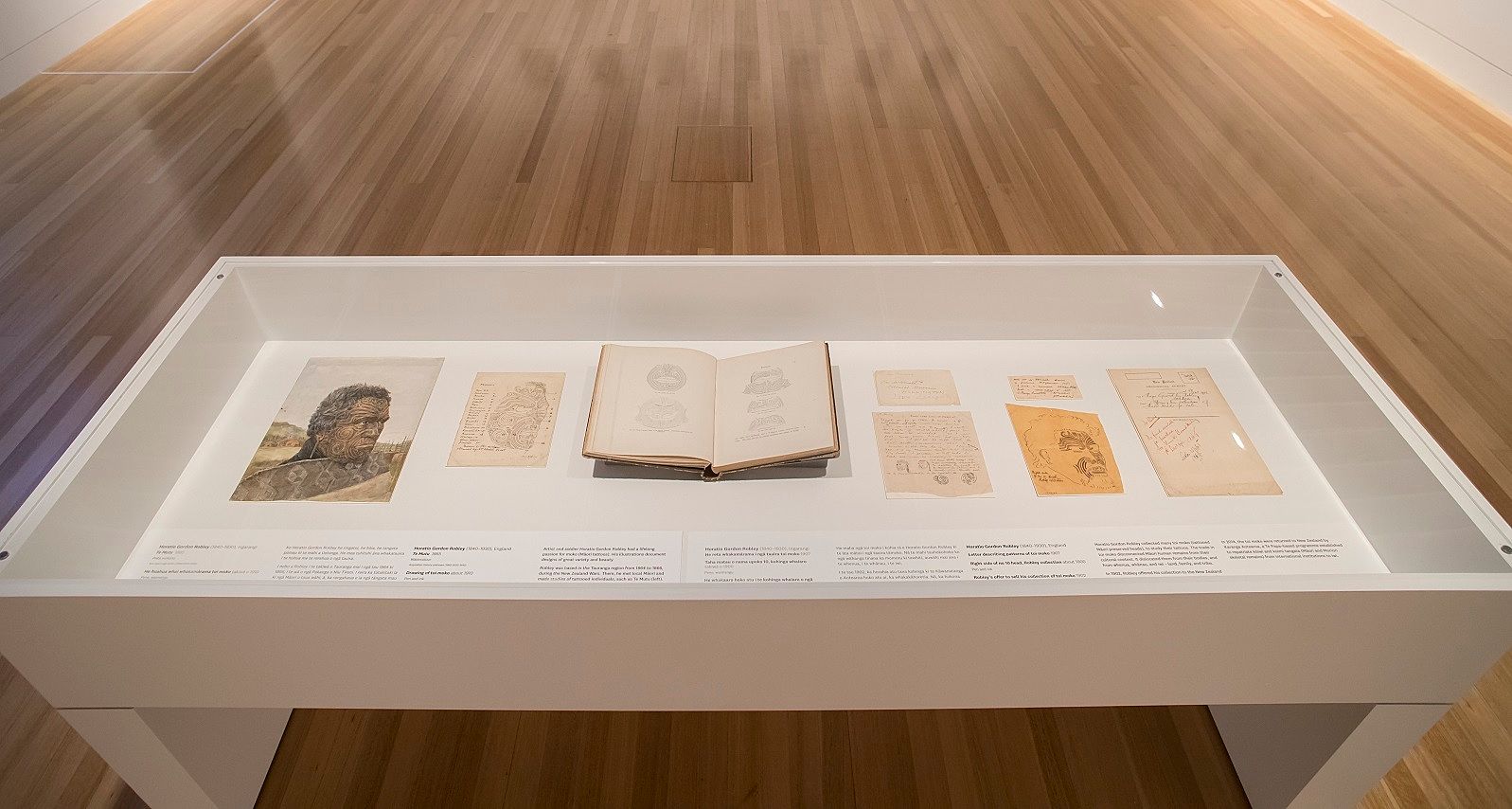

Upritchard’s Pākēhā head appears to be looking towards something out of sight, hidden behind a wall. I followed its gaze, and discovered what this head was straining to see. Shane Cotton’s Vee was the first piece which caught my eye; it depicts a Toi moko suspended within a dark backdrop, and was inspired by a Toi moko which was formerly held in the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris, and has since been repatriated to Aotearoa. The image was taken from Major General Horatio Robley’s book Moko: or Maori Tattooing, and the label explains Cotton’s intention for this artwork was to reclaim Toi moko into te ao Māori. No longer just a museum object, Cotton enables the Toi moko to be transformed back to a tupuna.

Alongside Vee is a set of seven untitled works, also inspired by the works of Robley. According to the exhibition label, each Toi moko has been obscured, enabling their tapu nature to be protected, while simultaneously invoking noa to allow them to be accessed. Slightly obscured and protected from curious eyes, these images are displayed as the heads would have been 100 years ago: in plain sight.

As I wrote this article, I asked a member of the front of house team if any visitors had commented on the presence of Toi moko in the galleries, and was told that it was Cotton’s works which most elicited emotions that were hard to explain. This was just the type of reaction I was hoping Cotton’s work would evoke, to create conversation about what was being seen, and its link to the practice and trade.

The researcher in me, determined to identify each of the tūpuna depicted in Toi Art, spent time in the gallery, Robley’s book in hand, carefully identifying the tūpuna. All seven of the tūpuna in Cotton’s works were part of Robley’s private Toi moko collection, which he attempted to sell to the New Zealand Government in the early 1900s, without success. In 1907, the Toi moko became part of the American Museum of Natural History collection, and in 2014 were repatriated to Te Papa. They now reside in the Te Papa waahi tapu where they are being cared for while research continues into their history and iwi connections. Robley’s collection was, prior to its return to Aotearoa, the largest single collection of Toi moko in the world.

The presence of Toi moko in Michael Parekowhai’s Détour are not so conspicuous; they are hidden amongst a forest of plastic trees, monkeys and Colin McCahon paintings. These four Toi moko were inspired by Robley’s drawings and the work of Theo Schoon. Visitors may be initially unaware of their existence, and for me this reflects their largely unknown presence in New Zealand society. Détour includes the display of a giant elephant, and the metaphor in this instance causes me to think that if we don’t talk about the history of their trade, they will remain unknown. It is when we have pōwhiri, following the repatriation of tūpuna from overseas, that this history is prominently revealed. These pōwhiri draw the attention of domestic and international media, who recognise that they are events of immense significance. It is in this concentration of attention that the reality of the work we do is most visible, it is where uri share their pain at the centuries of separation and elation of reunion.

Generally seen as a gory and gruesome aspect of Māori culture, the inclusion of Toi moko in the gallery space enables discussion around the meaning, creation, and representation of these tūpuna.

According to anthropologist and doctor Te Rangi Hīroa, the preserving of heads was dictated by two emotions: love and hate.

It is important to note that Toi moko have been part of Māori culture since before the arrival of Europeans. The process, known as pakipaki mahunga, was most likely developed in Aotearoa as it does not appear anywhere else in Polynesia. According to anthropologist and doctor Te Rangi Hīroa,6 the preserving of heads was dictated by two emotions: love and hate. In the first example, Toi moko were prepared to preserve the head of a rangatira or loved one so the family could mourn over them. When this happened, they would be brought out on special occasions, such as tangihanga, and were seen as “objects of esteemed beauty.”7

The second reason was to preserve the head of an enemy, to revile and to ridicule. Examples of this are present in some early drawings and paintings that depict heads atop the palisades of pā. With the arrival of Europeans came a third reason: trade. This particular trade began with the first voyage of the Endeavour and, given upcoming commemorations of Captain James Cook’s first meeting with Māori, it is fitting that this conversation be had now. Indeed, the first record of trade was made during this voyage – between Joseph Banks, the naturalist on board the Endeavour, and a man from Queen Charlotte Sounds. The height of the trade was between the 1820s and 1830s, coinciding with the period known as the Musket Wars (1818 to 1830). The wars were essentially an inter-tribal arms race, and one of the ways that muskets were obtained was through the trade of Toi moko, as they had become extremely sought after by explorers and traders. A market was created, and the rest is history.

An issue for me is the idea that Māori sold their own, and the related assumption being that Māori of the time saw themselves as one unified people. Though we might identify as Māori today, we are more likely to identify as being affiliated to a particular iwi or hapū. Generally, Māori identify as Māori to differentiate ourselves from those who are not. Before the arrival of Pākehā, we identified primarily through our whānau and hapū affiliations; there was not the same sense of a homogenous identity among tāngata whenua as there might appear today. In times of war, our tūpuna did what they could for the survival of their people, and engaging in the trade of their enemy was an extension of that; there was not the same feeling of kinship – they were the enemy.

In today’s society, from my personal and professional perspective, I see all Toi moko who come home to Aotearoa as our collective tūpuna, belonging to all Māori. However, I do acknowledge that this may not be a view held by all Māori, particularly with respect to the involvement of specific iwi in the trade of Toi moko. This view is further complicated by the fact that Māori are made up of many iwi, hapū, and whānau groups with their own history, their own whakapapa, and their own views on the past. Much has evolved over the last 250 years from collectors and explorers seeing peoples from other lands as non-human, savage, mere curiosities to be obtained, studied and displayed. It remains true that the trade of Toi moko was a dark period in our history, but there lingers a need to demystify the events and motivations of the past. We know past actions can never be undone, but in order to move forward we must talk about these histories and literally lay the past to rest.

[1] R. Richards, Pakehas Around Porirua Before 1840: Sealers, Whalers, Flax Traders and Pakeha Visitors Before the Arrival of the New Zealand Company Settlers at Port Nicholson in 1840 (Paremata: Paremata Press, 2002).

[2] W. W. Carkeek, The Kapiti Coast: Māori History and Place Names of the Paekakariki-Otaki District. (Wellington: Reed, 2004), 70.

[3] R. Taylor, The Past and Present of New Zealand with its Prospects for the Future (London: William Macintosh, 1868).

[4] D. Young, Histories from the Whanganui River: Woven by Water (Wellington: Huia Publishers, 1998); H. G. Robley, Moko; or Māori Tattooing (Papakura: Southern Reprints, 1987).

[5] The Trade in Preserved Maori Heads, Sunday Star Times, February 18, 2009.

[6] T. R. Hiroa, The Coming of the Maori (Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, 1958), 299.

[7] N. Te Awekotuku, Mau Moko: The World of Māori Tattoo (Auckland: Penguin Books, 2007), 46.