If you can fake it, you’ve got it made.

Why wait for an exhibition invitation when you can make it happen yourself.

Why wait for an exhibition invitation when you can make it happen yourself.

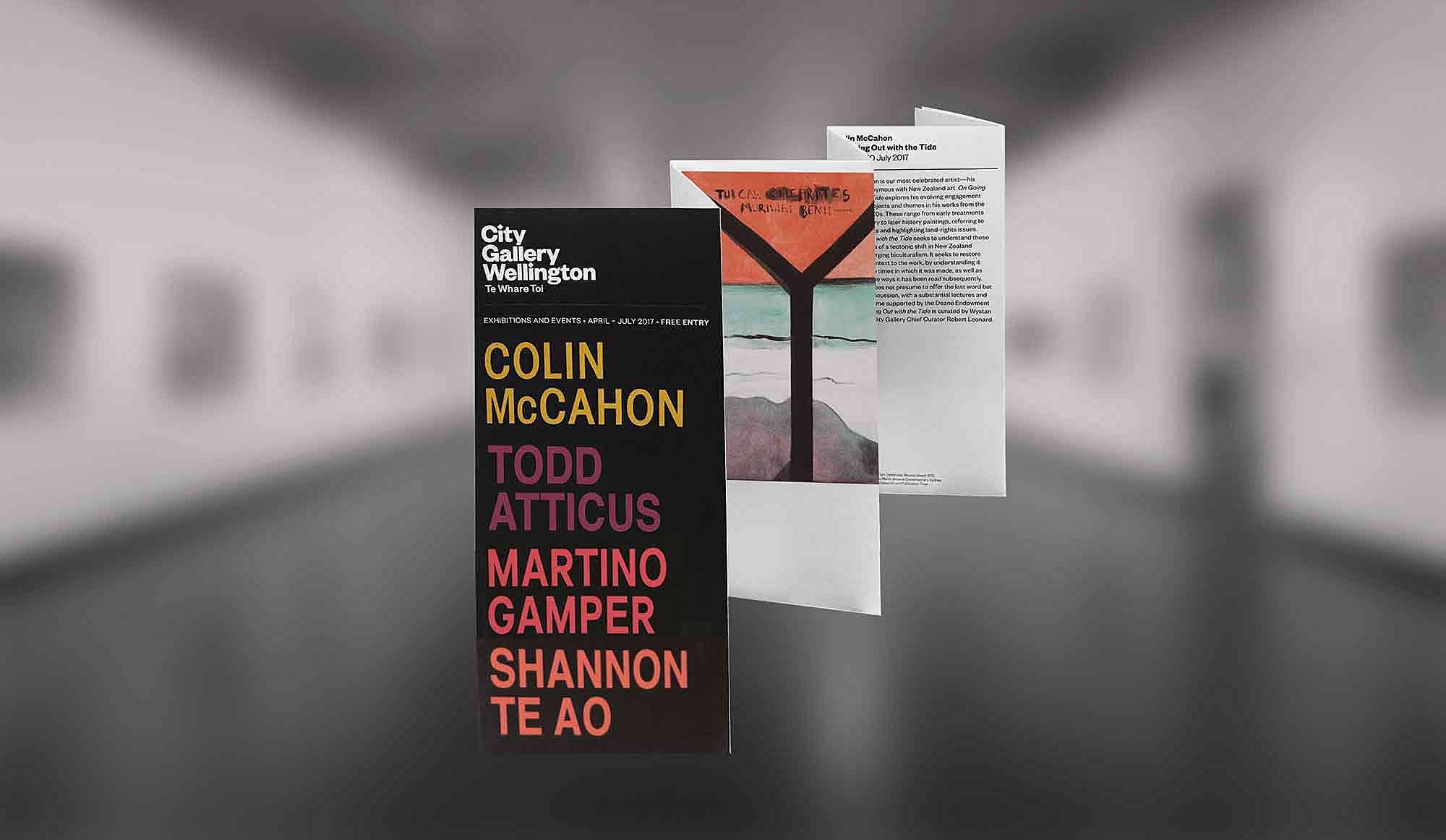

A clever stunt was pulled at the City Gallery last month. You may have noticed it immediately, you may have been duped and been completely unaware. It may even be lying on your very own kitchen bench. The trick advertised an individual as part of the gallery’s April-July season of exhibitions completely to the oblivion of the institution itself. This individual had in fact never exhibited an artwork in New Zealand before. 1000 forged City Gallery season brochure smuggled into the gallery with his name on it, ‘Todd Atticus’.

Throughout any given year, the City Gallery prints a flyer for each season of exhibitions. The flyer details the works on display and any associated events. Scattered throughout the gallery, as a visitor you are intended to take one with you, stay informed, and hopefully come back.

The brochure for April – July 2017 boldly displayed the names of four prominent New Zealand artists – Colin McCahon (we all know who he is), Petra Cortright (L.A based digital artist), Martino Gamper (creator of 100 chairs in 100 days), and Shannon Te Ao (installation and video artist and 2016 Walters Art Prize winner). Each of these individuals has their own Wikipedia page. Each is a familiar name to someone well-acquainted with the art world.

Yet by July, the gallery was unknowingly and unwittingly including a brand new artist in this star-studded line-up. Over a number of months, artist Todd Atticus, painstakingly recreated the brochures described above entirely from scratch. Every tiny detail from the original is accounted for. The City Gallery’s favoured typeface was even pinpointed by breaking down its websites source code. All of the icons were recreated. And the name ‘TODD ATTICUS’ proudly replaced either Petra or Martino’s names on the front.

Displaying your work in one of the nation’s most highly respected exhibition spaces is surely a career long dream for many artists.

Displaying your work in one of the nation’s most highly respected exhibition spaces is surely a career long dream for many artists. It is a space reserved for those who have influence and have ‘made-it’. To have your name printed on a gallery’s brochure, with a glowing write-up of your work inside, is a further affirmation. It would be, as Todd describes, like seeing your name in Hollywood lights; all those hours of painstaking creative work legitimised and valued.

Todd sought to question this curatorial process of selecting the lucky few by literally sandwiching himself next to the artistic heavyweights - and what better a chance to do this than by inserting your name alongside Colin McCahon’s? Without any curatorial assistance (or consent) he elevated his own status to be on par with that of one of New Zealand’s most revered artistic figures. This exercise reveals the extraordinary power of association, sought not only by individual artists like Todd, but by galleries themselves.

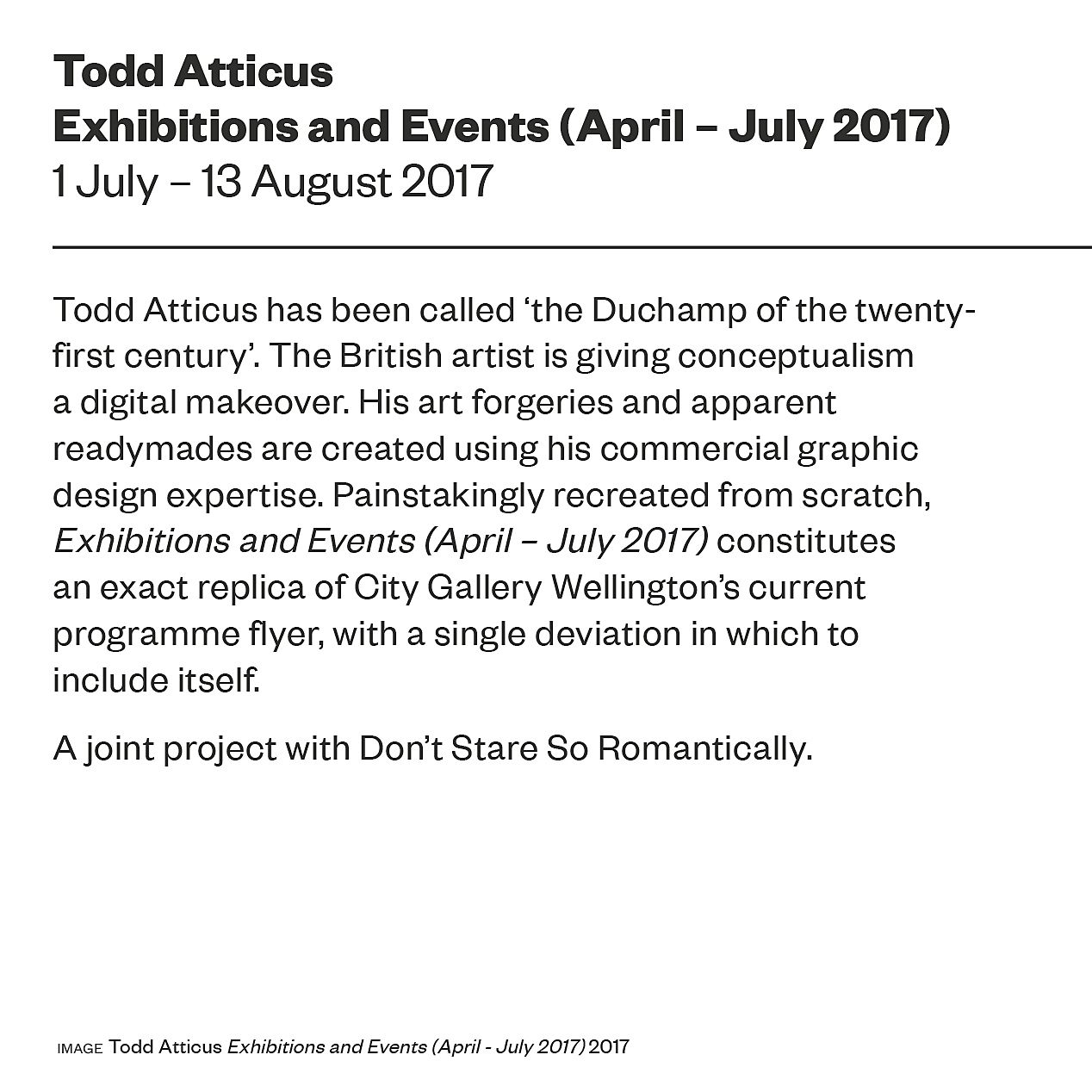

Todd trained in Fine Art in the United Kingdom however currently works as a graphic designer. Graphic design can tend to be dismissed in the art world as being merely a commercial practice. The associations with advertising being too strong. Yet Todd’s careful recreation of the gallery’s own commercial product, using his skills as a graphic designer, has challenged this dichotomy. The only personal gain for Todd from this endeavour was purely artistic, distributed without any commodity exchange (think of Felix Gonzales Torres and his piles of sweets and give-away posters).

With such a large volume of these fake brochures slipped in over a number of weeks, many must have spread their way around Wellington, or even the country. Slipped into bags, left on the coffee table, stored in the centre console of your car, put in the recycling; these bits of paper are intended to be temporary, disposable, and a purely informative part of your gallery experience.

With such a large volume of these fake brochures slipped in over a number of weeks, many must have spread their way around Wellington, or even the country.

But inside these fake brochures, a photograph of the brochure itself is featured as the visual of Todd’s ‘art’. Displayed proudly in the top panel, this meta composition transforms the brochure from a seemingly disposable piece of paper to an artwork in and of itself. The viewer’s experience of the gallery, probably on a Saturday morning, is disrupted by extending it far beyond the confines of the gallery’s walls.

Subversion and sabotage of the gallery space is however nothing new. This practice has been prevalent for a long time, taking off particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s. Todd Atticus describes himself in his forged brochure as ‘the Duchamp of the twenty-first century’. Similar to Duchamp, Todd challenges the institutional ability to legitimise and dictate what constitutes art. But there are many layers to Todd’s subversion that sets him apart from a Duchamp comparison.

A brochure is not a ready-made. Rather than placing a ‘Found’ and everyday object in an environment that elevates it into an artwork, Todd has manipulated a commercial product. This product also has too many ties to the gallery itself – a carefully pieced together and aesthetically pleasing brochure that is intended to catch your eye. Unlike Duchamp, Todd seeks to elevate the artist themselves rather than an object.

Reinvention is also not a new idea to the art world. The anonymous group of feminist artists called the Guerilla Girls have for a long time embarked on an activist mission to expose sexism and racism within the art world. Like Todd, they use humour and public displays to reveal the institutional hierarchies of power and challenge embedded forms of discrimination. Like Todd, they question a galleries ability to decide who are the insiders and who are the outsiders.

There are however facets of Todd’s reinvention that reflect trends in our 21st century modern lives. We have access to digital tools that enable an individual to legitimise themselves on their own volition (granted they have the traits that are valued by society as a whole). By digitally recreating the brochure from scratch Todd points out a fundamental challenge in our digital worlds – what and who grants legitimacy? What is in fact real and what is fake?

After weeks of letting the brochures sit in the gallery and be taken home by unsuspecting visitors, Todd eventually came clean. Pulling this kind of stunt is not devoid of some risks – is it illegal? Is it deeply offensive to the artists whose names were removed? What impact could a negative response have on Todd’s personal career?

Confessing that at first he thought the brochures had a ‘bizarre typo’, he deems the stunt “too clever, too funny, too well done, and ultimately too flattering” to be offended and call the lawyers.

The City Gallery responded in humour. Chief curator Robert Leonard posted about Todd’s ‘work’ on his personal blog ‘Rogue One’. Confessing that at first he thought the brochures had a ‘bizarre typo’, he deems the stunt “too clever, too funny, too well done, and ultimately too flattering” to be offended and call the lawyers.

Yet the gallery really had no other choice. To claim breach of copyright would put the gallery on shaky grounds. Perhaps not legally, but appropriation is a longstanding and contemporaneously respected art form. Sure enough, on it’s Facebook page the gallery itself described the stunt as a ‘crafty appropriation’.

Todd’s work exposes and demonstrates the two-way relationship between curators and galleries and artists. While the artists seek to have their names proudly displayed on a gallery brochure, the gallery itself is also reliant on attracting the influence and crowd-drawing appeal of the artists.

After realising that Todd’s name featured on the brochures, a friend of his (who has a highly developed knowledge of New Zealand’s art scene) genuinely believed that he had an exhibition there and asked to see it. A sure sign of the ‘artist’s’ success.