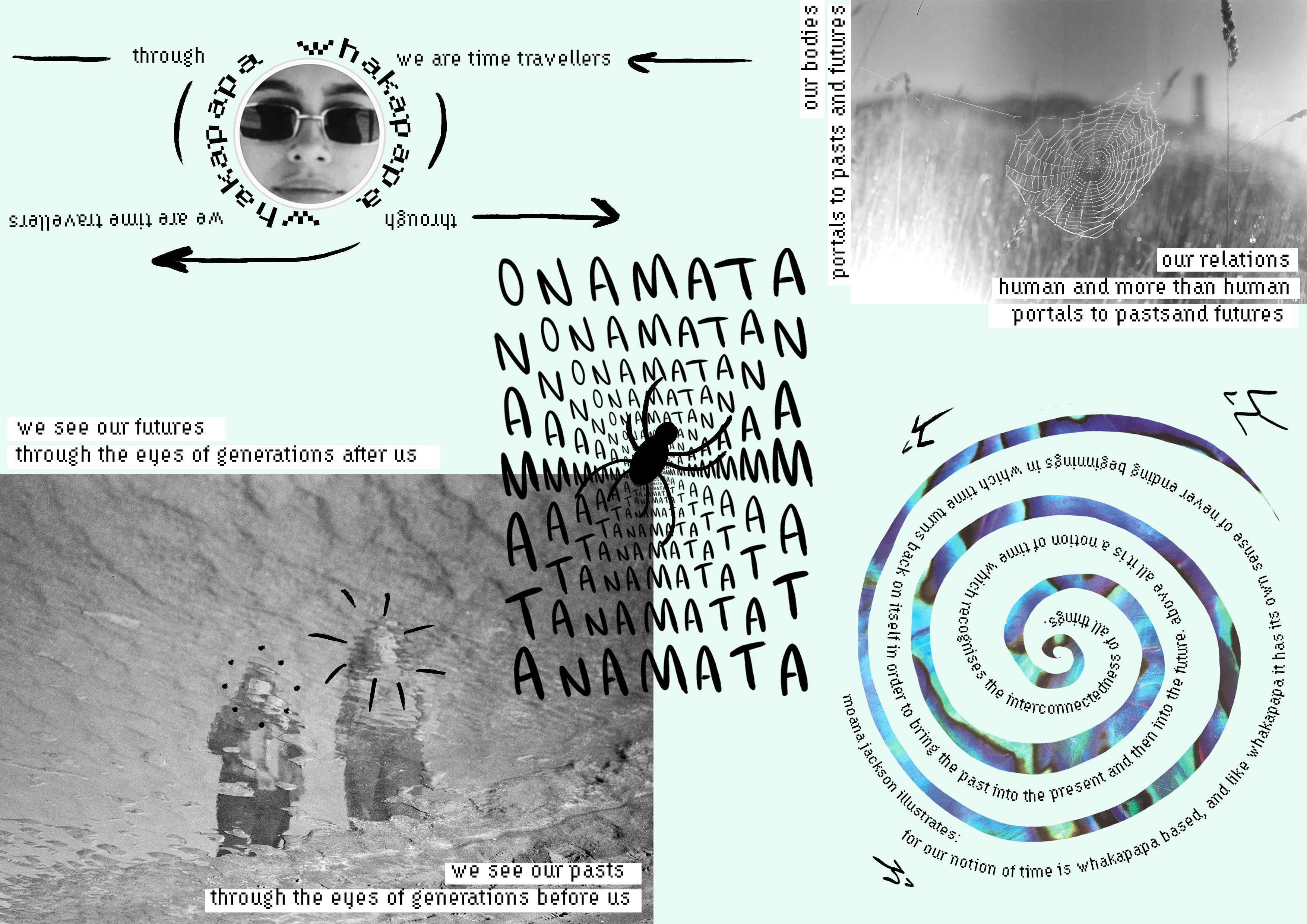

through whakapapa we are time travellers | we are time travellers through whakapapa

A guide to time travel by Ngaumutane Jones (Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu, Tainui, Tūhoe) & Hana Burgess (Ngāpuhi, Te Roroa, Te Ātihaunui a Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa).

through whakapapa we are time travellers

we are time travellers through whakapapa

words by Hana Burgess

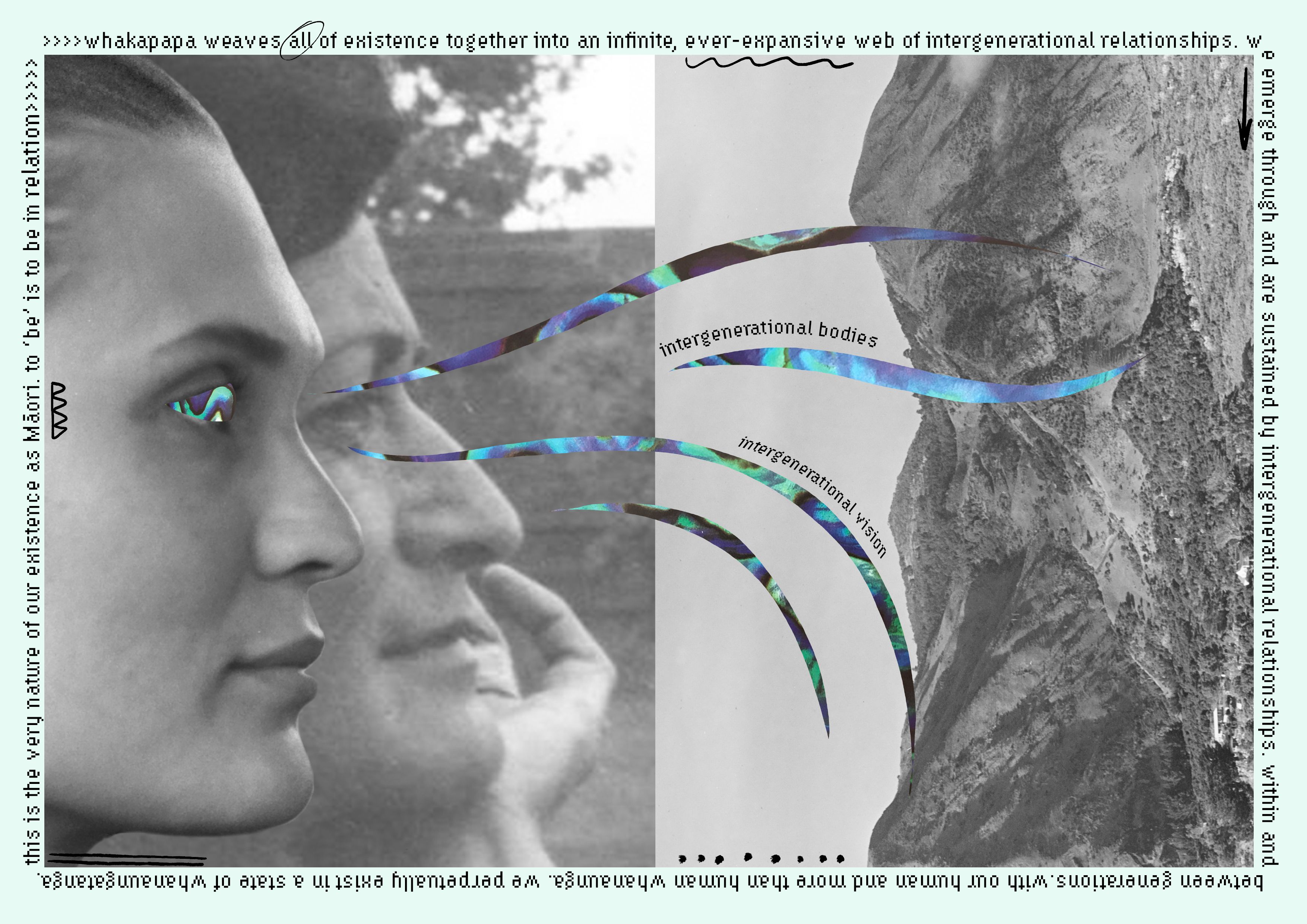

Whakapapa weaves all of existence together into an infinite, ever expansive web of intergenerational relationships.

Whakapapa is often translated as the Western concept of ‘genealogy’, which confines it to the past, to our human relationships of direct biological descent. However Ani Mikaere, in her thesis ‘Like Moths to the Flame? A History of Ngāti Raukawa Resistance and Recovery’, powerfully reminds us that whakapapa is much more expansive.

Perpetually rooted in creation, everything has a whakapapa, all phenomena, through time and space, seen and unseen, physical and spiritual. As humans, we emerge through and are sustained by our intergenerational relationships. With each other, and with the landscapes that constitute who we are, we exist in a state of whanaungatanga. This is the very nature of our existence as Māori. To be is to be in relation. This forms the basis of Māori conceptualisations of time. Moana Jackson (2013) notes in ‘He Manawa Whenua’:

For our notion of time is whakapapa based, and like whakapapa it has its own sense of never ending beginnings in which time turns back on itself in order to bring the past into the present and then into the future. Above all it is a notion of time which recognises the interconnectedness of all things.

Through whakapapa, generations collapse into each other. We are at once the past and future, our mokopuna and tūpuna, existing in the present. This is how we understand, and travel through, time.

The Western concepts of ‘past’ and ‘future’ occurring along a linear trajectory of time do not have a direct translation in te reo Māori. But we do have the concepts onamata and anamata. In short:

mata – eyes

onamata – the eyes of those who have come before us

anamata – the eyes of those who have come after us

In essence, this tells us that we see and understand the time that comes before us, through the eyes of our tūpuna, and we see and understand the time that comes after us, through the eyes of our mokopuna. Time is whakapapa based, and onamata, anamata is how we can see, and move, through it.

Here, the notion of ‘the present’ is not central to our reality. Indeed, there is no direct translation of the present in te reo Māori. We comprehend the present as a fleeting moment where pasts and futures meet. Each and every thing in existence is a fleeting embodiment of the meeting of past and future generations, in what Moana Jackson describes above as a “series of never ending beginnings”.

Each of us is intimately connected to innumerable past and future generations, our tūpuna and our mokopuna. Multiple generations unfold from us, like infinitely cascading intergenerational currents. The physical plane of our existence is but a thin layer of who we are. Like us, time is expansive.

We are timeless. Time collapses in us.

Our bodies, our vision, intergenerational.

As points in our whakapapa, the fleeting meetings of pasts and futures, we are portals through time. So, too, are our more than human whanaunga - awa, maunga, moana, and creatures that inhabit throughout.

We can activate these portals through whanaungatanga, by being in good relation through whakapapa.

By being in good relation through whakapapa, we can know how something came to be, how it relates to wider existence, and how it will come to be. We can see and travel through the pasts and futures that endlessly cascade from each of us, and we can let this tell us how to live well in the world – how to move in this fleeting present in a way that nurtures us intergenerationally. In a way that nurtures our tūpuna and mokopuna. It is through time travel that we can really see the present. We can see ourselves.

We can swim in the moana, and feel the love between Tangaroa and Hinemoana. We can see our tūpuna arriving by way of the stars. We can see them surrounded by an abundance of kaimoana. Fat kina, pāua and kōura. We can see luscious māra surrounding our whare. We can smell the vegetables grown from the earth. We can hear a cacophony of native birdsong. We can see more clearly the impacts of settler colonialism, and envision futures beyond, where our mokopuna once again have stomachs full of kaimoana, and flourishing māra. We can see what we need to do today to make this happen.

We can be in relation with our loved ones, with pasts and futures that collectively make us who we are today. We can be our expansive intergenerational selves. We can listen to music, dance, sing, and be transported through time as we do so. We can laugh, and hear generations of aunties and uncles cackling alongside us. We can make art that reflects our pasts, and calls forth the futures we desire. We can rest, we can wonder, we can dream through time, to pasts where our tūpuna could look up at the sky and see a wealth of knowledge, and to futures where our mokopuna can do the same. We can see, at once, multiple generations unfold in endless cascades. We can guide and be guided by the infinitely cascading intergenerational currents that make us who we are.

We can be in good relation.

We can time travel.

References and further reading

This piece was based on theorising by Hana Burgess and Te Kahuratai Painting, ‘Onamata, Anamata: A Whakapapa Perspective of Māori Futurisms,’ in Whose Futures? ed. Shannon Walsh and Anna-Maria Murtola (Auckland: ESRA, 2020), 205–233. (This paper has a comprehensive list of references for this work. You can contact Hana if you would like a copy.)

Jackson, Moana. ‘He Manawa Whenua.’ In He Manawa Whenua, edited by Leonie Pihama, Herearoha Skipper and Jillian Tipene, 59–63. Hamilton: Waikato University, 2013. https://www.waikato.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/321904/HMW-Conference-Proceedings-Inaugural-Issue_FINAL.pdf. Recording of his kōrero available here.

Jackson, Moana. ‘Where to Next? Decolonisation and Stories in the Land.’ In Bianca Elkington, Moana Jackson, Rebecca Kiddle, Ocean Ripeka Mercier, Mike Ross, Jennie Smeaton and Amanda Thomas, Imagining Decolonisation, 133–155. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2020.

Koroi, Haylee. ‘In Right Relationship – Whanangatanga.’ In Climate Aotearoa: What’s Happening and What We Can Do About It, edited by Helen Clark, 15–41. Auckland: Allen & Unwin, 2021.

Mikaere, Ani. ‘Like Moths to the Flame? A History of Ngāti Raukawa Resistance and Recovery’ (Te Kāurutanga thesis, Te Wananga o Raukawa, 2016). https://tetakupu.wananga.com/products/like-moths-to-the-flame

In addition we acknowledge the futurists in our lives, alongside whom we think and time travel; our kaumātua, tuākana and tēina, our whānau, friends and communities. We would especially like to acknowledge the artists, musicians and DJs in our lives, alongside whom we do our best time travelling. Kei te mihi, kei te mihi, kei te mihi.

Hana and Ngaumu collaborated on this zine over summer 2020/2021, as they yarned about the nature of time and space in between lockdowns. This zine was all a bit of fun really, it is a combination of Ngaumu’s mahi as a multidisciplinary artist, and Hana’s mahi as a kaupapa Māori researcher/creative. ‘through whakapapa we are time travellers’ is a visual exploration of the fact that as Māori, we are (and always have been) time travellers.