Spec-Fic Month: A Conversation with Karen Healey & Rhydian Thomas

During June 2017, we're celebrating the fantastical, futuristic, and magical with excerpts, interviews, and poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand spec-fic authors. Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett talks to Karen Healey and Rhydian Thomas.

During June 2017, we're celebrating the fantastical, futuristic, and magical with excerpts, interviews, and poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand spec-fic authors.

Karen Healey is the author of four books, most recently the futuristic adventures, When We Wake and When We Run. Rhydian Thomas is a writer and musician from South Wales who lives in Wellington. His debut novel, the dystopian satire Milk Island, came out in 2017. Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett talked to them about spec-fic, escapism, and why literary fiction can be so fucking boring.

Sarah Jane Barnett: Tell us about how you started writing and the path that led you to write speculative fiction?

Karen Healey: I started writing because I made up stories for my siblings to act out, and they inevitably got bored with my petty tyranny. They also forgot lines, or didn't do the actions exactly as my tiny controlling brain had conceived them, and the special effects were frankly dismal. So I wrote them down instead.

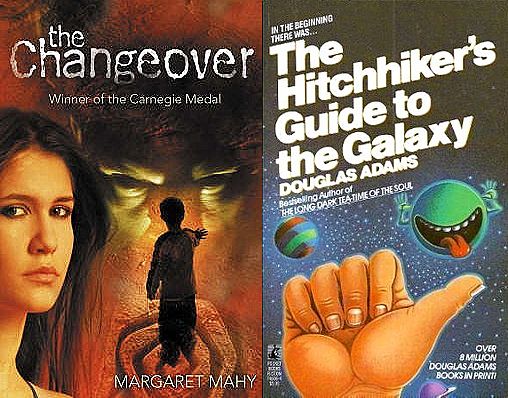

My most formative influence is probably the work of Margaret Mahy, from The Lion in the Meadow to The Changeover. Her imaginative flair and sense of play with language were infectious. As a teenager, I wrote fanfic in speculative worlds, and never stopped. For me, ‘writing speculative fiction’ is synonymous with ‘writing’ – I read literary fiction rarely, and detective and romance fiction voraciously, but I haven't written any. Yet.

I remember making my own Famous Five style 'books' in primary school, but they had no moral teaching and always included laser guns.

Rhydian Thomas: I have to admit that I'm still pretty unfamiliar with the genre of 'speculative fiction' as its own distinct style, so I'm not sure how I've ended up writing that specifically. I really do think that every kind of human story – even an autobiography or a water-cooler yarn in the workplace – is necessarily speculative in one way or another.

As a child, I read a lot of Enid Blyton, Steven King, Douglas Adams, Sue Townsend, and Welsh-language books. Somewhere formative along the way, I decided I was a writer and that's been stuck with me since, like a secret illness. I remember making my own Famous Five style 'books' in primary school, but they had no moral teaching and always included laser guns and football. As a teen, writing lyrics for imaginary heavy metal bands got me going again, and I've just carried on from there, for better or worse.

Sarah: A common theme is that you both wrote stories from an early age. I remember doing the same, and many of my ideas were drawn from the fantasy novels I loved as a teenager. Those books still hold a big place in my heart. What do you think is it about speculative fiction that attracts readers, and beyond that, hard-core fandom?

Rhydian: For me, it was about escape. The town I grew up in was fairly grim for young kids, so those alternate worlds with their lore and unique universes offered a chance to escape reality while reading, and then incorporate that into how we played. And my friends and I took our characters very seriously, whether it was Tolkien's cast of Middle Earth or the Power Rangers or even the made-for-TV Sharpe series about Napoleonic riflemen, which we dutifully acted out within the bounds of that particular battleground (though I suppose that's not truly speculative, just a semi-fictionalised history).

In a bigger sense, I'd guess that people love speculative fiction and otherworldly landscapes because we as humans crave anything that can disembody us from the painful reality of living in a finite, often predictable and brutal world that offers very little magic and engages even less of our imaginations.

What if gender equity was totally normalised? I've never seen that in the real world, but I've found it in speculative fiction.

Karen: To me, and I think to a lot of other readers, the appeal of speculative fiction is the what-ifs. What if you really could go to sleep for a hundred years and wake up in a world that had changed without you? What if your small town really was a magical place? What if all the stories were real? Speculative fiction is all about speculating, about the past, present and future – here's the world as it is, but what if it were different?

As Rhydian notes, that can have escapist appeal, and escapism is hugely valuable, especially if we're escaping from a grim brutality. But what-ifs can also be transformative. I've encountered ideas in speculative fiction that promoted not escapism from my own circumstances, but engagement with them. What if gender equity was totally normalised? I've never seen that in the real world, but I've found it in speculative fiction. That we can imagine it, that we can dream in that direction, is something that's both encouraging and motivating for me.

I think readers love entertaining those ideas, and following characters through them. In my experience, hard-core fandom comes from engaging with worlds and characters – and in many cases, fans seek to fill in perceived gaps or writing against the preconceptions of the established world, producing what-ifs of their own. Tolkien's Eowyn, one of my first favourites, reportedly came from Tolkien engaging in a what-if of his own. What if the witches' prophecy about Macbeth, that he could be slain by 'no man of woman born,' meant that he could be slain by no man but a woman?

Sarah: That nicely segues to my next question. Rhydian, the dystopia of Milk Island could be read as a warning. Karen, in When We Wake the world is suffering from climate change and discrimination. When creating a speculative world you can remove sexism, racism, and class issues, or explore those issues in heightened ways – and Karen, your books have been praised for the diversity of their characters. As world-builders, do you feel a responsibility to address social issues?

Karen: I don't think that writers in general have a responsibility to address social issues, nor do I think art must have a moral purpose. That said, I think any writer whose world is devoid of diversity isn't paying attention to human history or reality, and thus isn't engaging in solid world-building. I'm completely uninterested in speculative worlds where everyone's white and straight, and this is considered totally unremarkable.

I do feel a personal responsibility, and my own work is often didactic. I don't think all writers are obliged to have their readers engage with ethical issues or think critically about society, present or future, but I also don't apologise for that aspect of my own writing. I write specifically for young people, who are inheriting a thoroughly messed up world, and my science fiction explores some likely consequences and proposes some solutions. Some readers see preachiness. Others see affirmation of their own ideals.

The town I grew up in was fairly grim for young kids, so those alternate worlds... offered a chance to escape reality.

Rhydian: I'm a little torn on this. On the one hand, I'm deeply naive and idealistic, and I can't help but express sincere political frustration in my writing. On the other, I feel no personal responsibility at all to propose my own solutions to New Zealand's problems or try to mobilise hope for a better future. That's partially because I often doubt my ability to universalise 'the good' for everyone else (especially as another generic white Wellington guy), and partially because I'm still figuring out what I believe through my writing.

In Milk Island, I've fixated on some of New Zealand's major social and political problems in a sort of 'reductio ad absurdum' kinda way, and I'm not sure that's particularly helpful or prescriptive. But I do believe humour can occasionally transcend ideology and other social boundaries, so I've tried to focus on taking the piss and taking power away from the powerful in the novel. For me, a big part of rejecting that old order – the one that has landed us where we are, politically and socially – is making it look ridiculous and nostalgic in its contemporary context. So if the book is a warning about the future of New Zealand, it's something silly like a navy blue dildo taped to a lamppost somewhere along State Highway One rather than a 'Caution: Landmines Ahead' sign.

Sarah: Much has been written about the ‘genre’ versus ‘literature’ divide. One of the issues is the value judgement that comes with it – that ‘literary’ fiction is more worthy than ‘genre’ fiction. In reality, genre writing is a subset of the diverse work that makes up ‘literature.’

As an author, there’s sense in simply ignoring the issue and letting readers decide the ‘worth’ of your work, but as some commentators have suggested, New Zealand genre writers receive little public funding. While the distinction between literature/genre seems to be lessening – the Man Booker long listing of Anna Smaill’s The Chimes is a recent example – a 2012 sci-fi issue of the New Yorker was criticised for not including sci-fi by writers from the genre. How do you feel about the ‘genre’ versus ‘literature’ divide?

Risks, weirdos and niches are a lot less tolerable when the return on investment is all that counts.

Rhydian: I don't have much personal experience of this, especially as a first-time novelist. I don't think about genre vs literary fiction; I don't care what my work is called, and I haven't tried to get public funding for anything yet. I'm inclined to agree that there's some degree of snobbery within the New Zealand publishing industry about what 'real writing' is, and I can agree with Peter King's article that there's an ongoing project to build moats around the castle, but I'm used to that way of thinking because I've been making and releasing punk and hardcore music here for the last decade or so.

There are definitely many problems with arts funding, and too many to unpack here properly. Most of my qualms are political: an overall philosophy trickles down from a Government that's mainly interested in the potential financial and PR benefits of any given project, and that influences decisions made by funding bodies on some level, whether conscious or not. Risks, weirdos and niches are a lot less tolerable when the return on investment is all that counts in evaluating what's worthwhile and what isn't. Especially given that underlying pressure to consider arts funding as a kind of roundabout R&D grant for New Zealand's tourism industry, and the broader underfunding of arts organisations like Creative New Zealand in inflation-adjusted terms since National took office – the sector is at least $200m behind an 08/09 baseline, and Creative New Zealand's appropriation was still frozen in last month's Budget.

My problem with literary fiction is that so much of it is so fucking boring.

Karen: My problem with literary fiction isn't that it's more elevated or gets more awards, although I agree with Rhydian that Government support of the arts is ludicrously low. I should add, though, that I'm going to be one of the Ursula Bethell Writers in Residence at the University of Canterbury this year, which has also supported other YA and spec-fic writers. I appreciate the University of Canterbury's commitment to quality, whatever the genre.

So, yeah, my problem with literary fiction is that so much of it is so fucking boring. There's certainly plenty of crap in other genres, but I can usually tell from the first few pages of spec-fic or romance whether I want to keep going. So much lit-fic starts off well and then wanders up its own ass. If I put it down, I never pick it up again. I studied English literature for four years, and that was probably my limit for enjoying skillfully-written, largely-plotless character meanderings on the ostensibly universally human condition.

Which is not to say I don't read and love some lit-fic, because I do. A couple of months ago, I read Rachael King's Magpie Hall, which is the gothic story of a young woman that a university professor cheats on in order to feel young again, and it's great! She has a story of her own, and a history of her own, and a life that has nothing to do with that guy, who is a character who has had way too many stories written about him. Every single one of those novels would have been better with werewolves.

Sarah: World-building is considered the bedrock of good spec-fic. Writer Brandon Sanderson has been quoted as saying that it’s the ‘limitations’ placed on a world’s systems that make them interesting. How do you go about building a world that feels real but fantastical at the same time? Do you agree with Sanderson?

Karen: I love world-building so much, and I think Sanderson's totally right: a world in which anything at all can happen isn't much fun, but a world which operates under certain rules and restrictions provides tension and drama, as characters work within those rules (and occasionally break them).

I also love world-building which doesn't fall into simplistic stereotyping, but takes into account the interesting ways people construct and reconstruct societies. One of my favourite world-building writers is N. K. Jemisin, who creates multiple complex cultures in each individual series, and then has her characters operate within (and sometimes against) cultural expectations. As a result, her work feels vibrant and real, even though it's taking place in fantastic worlds.

Rhydian: World-building is the best part for me too, and it was the part that took the longest in preparing to write Milk Island. Strange that, because its world is almost pre-built in reality, but that's where moral and legal issues arrived in terms of how to represent real-life figures and organisations, and where the fun of near-future speculation began. So in many ways, it was more like world-stretching, or world-skewing for me.

Character names are something I spent a lot of time on in Milk Island, and rebranding the South Island's various tourist attractions and correctional facilities in believably dystopian Kiwi rhetoric was a challenge.

The limitations of that world were balanced with how far I could distort real-life expectations of New Zealand's future while suspending disbelief in the premise. I'm a big believer in that balance, and it's as important to me in my enjoyment of writing it as it may be to keep someone reading. I found world-building to be a process of turning those silly one-liners and irresponsible what-ifs into a coherent political system. That world needed to respect and disrespect the reality of life in New Zealand enough to (hopefully) get a laugh while keeping the plot logical and the reader invested. I really didn't want to write a long-form version of a satirical newspaper article, and world-building was crucial to go beyond that one joke, one issue, one perspective. I found Will Self's The Book of Dave or The Butt to be good models for this – their conceits are jokes you could tell in a sentence, but they still have an emotional weight and drive to their narratives.

Sarah: How important is language in world building – from the names of characters to the vocabulary of a particular society?

Karen: Language is vital. Obviously, it's the only way an author can communicate anything at all to the reader, but it's also essential in conveying the sense of a place, or the concerns of a character. I'm co-writing a second world fantasy at the moment, with cultures that aren't Aotearoa New Zealand, and characters who don't speak or think in English – although I am writing them in English, using the Latin alphabet.

My co-writer and I spend a lot of time just discussing language – would this character use farming or fishing metaphors? Is this one going to compare another character's beauty to that of wooden or metallic jewellery? What syllables would appear in the names of characters from this insular, mono-cultural nation, as opposed to the characters from this more multi-cultural, trading city? Should we use 'magnet' or 'lodestone'? What proverbs are appropriate?

Language in world-building can even alter symbology – pink to us, in 2017 Western society, is a colour signifying femininity, but that's purely arbitrary. It used to be a very masculine colour that no good woman would dream of wearing. In one of our cultures, pink signifies those who are sworn to the god of merchants, travellers, traders and borders, because sunrise and sunset are pink, and they are the borders of the day. They're a people in a land of harsh winters, so white is the colour of death. And so on!

Rhydian: It's crucial, especially in terms of the suspension of disbelief I was talking about in the last answer, and especially when a future setting is a real place like New Zealand. Character names are something I spent a lot of time on in Milk Island, and rebranding the South Island's various tourist attractions and correctional facilities in believably dystopian Kiwi rhetoric was a challenge.

Luckily there's a rich linguistic folklore available in contemporary times to jump off: Landcorp... Peach Teats... The Sensible Sentencing Trust... The Mad Butcher... Fonterra... The All Blacks... Crosby/Textor... dah-dah-dah/boom-boom, etc.

Sarah: To finish, who are the authors that inspire you?

Rhydian: I'm still stuck in the early twentieth century, to the annoyance of every proper reader around me. I don't care if it's as much of a cliché as suggesting someone watch The Wire, but Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Céline is the central text of flighty, uncommitted nihilism, and I still can't shake it. I'm enjoying Suicide by Édouard Levé at the moment. In terms of influences on Milk Island: Will Self, Sue Townsend, Michel Houellebecq, André Gide, and George Oppen.

Karen: Dear reader: I think you should stop reading this article right now and Google the name 'Sofia Samatar.' She is an extraordinarily good writer of short stories and novel-length works (and literary criticism too, should that be your bag). She considers language and the way it works with insight and care. She creates incredible, but totally credible, worlds. Her sense of character and metaphor are brilliant. She's amazing. Your life will be enriched by her work. I'm not kidding. Google her. Do it. Now.

BUT WAIT – READ THEIR WORK!

Read an excerpt from Milk Islandby Rhydian Thomas.

Read an excerpt from When We Wake by Karen Healey.