This Is Sheffield: Florian Habicht and 'Pulp: A Movie About Life, Death And Supermarkets'

Florian Habicht's documentary about Pulp and their home city, Sheffield, isn't just the best music documentary this year - it points a way out of biography and historicising into a better way of understanding acts we love. Joe Nunweek chats to him about brutalist housing projects, doing his subjects justice, and Pulp's last show.

Sheffield’s Park Hill is one of the great and solemn monuments to post-war Britain’s ambitious, dogged determination to house its most needy. All surfaces of cast concrete and level lines of sight snaking across the landscape, its 3000 people traversed its blacks on open sky paths big enough to drive a milk float from door to door on, wide enough for neighbours to meet each other and socialise. It included a shopping precinct, a primary school.

Over time, its huge unadorned surfaces became a magnet to graffiti, the most iconic of which is a great white scrawl its author leant over one of the great bridges to write: “CLAIRE MIDDLETON I LOVE YOU WILL U MARRY ME”. It was a damp and lonely Thursday, years ago.They never did it, although he often thought of it.

As we sit in one of the Civic Theatre’s antechambers, Pulp: A Film About Life, Death And Supermarkets director Florian Habicht is explaining to me what happened next. The story goes that Claire found the gesture embarrassing and over-imposing. They’d only been dating a year. They broke up three months later, and she died too young. In the meantime, Park Hill was partly privatised, its road-facing edifice converted into a bunch of geometric, boxy squares of millennial iPod colour.

A quote from one of Sheffield’s two great pop acts now invites in upmarket penthouse renters and social media companies: Don’t you want me, baby? The “I LOVE YOU WILL U MARRY ME” has been illuminated in neon tubing. Claire Middleton’s name has been left to fade. The pillows in the expansive new pre-furnished units are monogrammed with the partial phrase, a year of okay sex and bad decisions immortalised in thread.

There was a Sheffield Florian Habicht had in his mind, but this was the one he arrived in one grey autumn day. He had a fortnight to make a documentary about the other great pop band that Sheffield threw up. To know the city would be to know Pulp, but he needed to do it before both vanished.

*

Tall, wiry and eccentrically dressed, it’s easy to start drawing comparisons between Habicht and Jarvis Cocker. He shares the Pulp frontman’s tendency to look up expectantly and grin after an anecdote, and he’s inherited a similar polite patience when faced with the same questions again and again. More importantly, they shared a very similar idea of what a documentary about the best band of the 1990s should look like.

“I first heard Pulp when I was living in Ponsonby, on Tole Street, with Jacqueline Wilson (the dancer/choreographer)”, he recalls. “She was doing a solo performance thing at the Watershed and she showed it to me and she gave me this private rendition of this dance – to “Bar Italia” from Different Class. I liked her dance a lot and I liked the music, so she lent me the whole album.” It’s the closer on the band’s most famous album, a chorus with a Broadway number heft that conceals the desperation of people getting kicked out of the last bar as people go to work. He was hooked.

Though some might expect – nay, demand – that someone who was going to do a documentary on a band double as their scholar, Habicht’s attitude is refreshingly straightforward. He’d heard three of their albums before the documentary, worn the CD’s at the edges, didn’t need context or biography to give the songs a new (or 'correct') meaning. Some of the band’s own wonderful video projects, like the “Do You Remember The First Time” short feature that overlaid interviews with people about their first fumbling sexual experiences over shots of the same locations years later, feel like they anticipate his documentary work. But it’s coincidence, a classic case of parallel development.

“I didn’t actually see the videos, I just saw the music, and I just my own music videos going on in my head. It wasn’t until much later, when I was making the film, that I checked out their videos and I realised there were quite a few I hadn’t seen. “

In late 2011, when his film Love Story was set to secure a London premiere and he was invited to request guests, the choice seemed obvious. “I was thinking about my friends in London, and there were maybe two handfuls of those, and then Pulp came to my mind – I can’t exactly remember the details, it just came to me.

“I didn’t even know how to get hold of him. A friend of mine in London gave me a contact to get hold of his publicist, and then I had other mutual friends that actually knew Jarvis – so I put out the invite, but I didn’t hear back and so I simply shrugged it off and thought ‘long shot’.”

Which could have been a fitting end to the story, since missed connections are the stuff of pop music. But then Florian got the call – Cocker had seen the trailer, and he wanted to meet for a chat. “So I hired a cinema and put a private screening on for him one morning.” And if you think that sounds a little like the overture of a Pulp song, you’re not alone.

“We had really similar ideas of what film we want to make, “ he recalls. “Originally he wanted Pulp to play in front of Park Hill, but the Council didn’t allow it so then he had this idea to make a film just following the lives of people that live there before they come along to the concert. Whereas my idea was to make a film about the people of Sheffield, rather than one focused on the band. “

It might seem counterintuitive – docos like End of the Century and We Jam Econo have geared us for a platonic ideal of well-made, straightforward band biographies – but it’s what everyone involved wanted. “I think that’s why they hadn’t made a film in the past. They all want to hear about controversies and drugs and Michael Jackson at the Brit Awards. “

“The morning after My Legendary Girlfriend. Trying to get things done but ending up on a tour round the fleshpots of Sheffield in a T-reg Chevette. Wybourn, Brincliffe, Intake - All these places really exist and maybe these adventures still happen there - I wouldn't know; I don't live there anymore.”

- Jarvis Cocker on “Sheffield: Sex City”, from the sleeve notes of Intro: The Gift Recordings, 1993

Cocker left Sheffield in 1988 or so to study film at St Martin’s in London, and the rest of the band drifted inexorably south from there. His own memories, as related to Habicht in the film, were a set of locations where he passed his late teens and early twenties – his Saturday fishmonger’s job, parks where he might have copped a feel, pubs he might have been thrown out of. “I imagined it as “Sheffield: Sex City”, or in “Babies” - young girls hiding in closets. When I got there it was bleak, dark, cold and wet - like arriving in Hamilton late in the afternoon. There is quite a bit of magic there, but you have to find it. I think most things I stumbled across - but he gave me the number of his sister, and a good friend of his, and he gave me a tour, and I had his book, Mother, Brother, Lover. “

Habicht’s ended up capturing moments of a Sheffield that’s receding: there’s an elderly knifemaker who would have started his trade when the city was still an industrial power and remembers making blades for Elvis’s band; meanwhile, the unrestored back end of Park Hill houses pensioners who each raised seven kids solo and can evaluate the merits of Blur vs Pulp (“Pulp have got lyrics that make you think, and I like music that makes you think. “)“Half of it’s new, it’s been done up and is modern living,” Habicht tells me. “The other half, they’re slowly kicking people out and just doing it up – but it’s not working. They’re not selling as many apartments as they thought they would.”

That might have been because of nearby Castle Market, the sprawling centrepiece of the Sheffield nervous system Habicht documents. A labyrinthine indoor affair, it’s not quite like anything else: think a version of K Road’s Mercury Lane that took up a whole block, or a more pragmatically lit shantytown from Blade Runner. Though Habicht filmed in a church at one point, he found that the Market was where a number of his favourite characters preferred to congregate. Cocker himself remembers a hard day’s filleting followed by an hour soaking his hands in bleach (“To go to a teenage party smelling of fish isn’t going to help your chances of getting off with someone”).

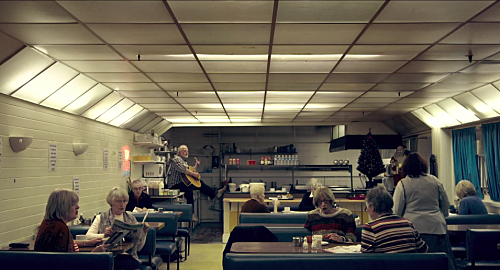

Best of all is the Victoria Live At Home Choir, a set of nice old ladies and gents performing “Help The Aged” virtually a-cappella in a windowless tearoom. “They really did not want to sing the ‘sniffing glue’ line in ‘Help The Aged’”, Habicht recalls, “and if you watch the film we sort of skip over that.” All the way through, they stare intently at campy old horror mags and DIY catalogues, and it’s a little like they’ve all been stirred out of their elevenses as one and launched into a musical number. It turns out they were reading the lyrics, carefully glued into the pages. “I really like it when you have problems and then you have to solve them, and you come up with good ideas out of it – if they’d learnt the words to the song that scene wouldn’t have been as interesting." It was good timing – despised by new developers and the upwardly mobile as an eyesore, Castle Market was closed for good late last year.

“Jarvis didn’t even know if that Sheffield still existed – some of those markets, some of those characters,” Habicht remembers. “He’s been splitting his time between London and Paris. It was such a big thing for them, that concert – they felt so nervous, so I do think he’s got something to prove.” So did Habicht – Kaikohe Demolition (2004)and Love Story (2011) found him bowling up to the garrulous locals of Northland and New York City, and they’d bowl right back. Northern England is different.

“They’re camera-shy in Sheffield. Whereas New Yorkers, and people in Kaikohe – it’s like they’re trained or something, whereas people in Sheffield, I don’t know if it’s technology or what, they’re not that they’re not welcoming people – not all dour – but they did not like to be filmed.” You can still hear him in the film, blundering into the occasional profound and unexpected question like an affectionate Great Dane, but there’s patient reconnaissance too.

“People took me on tours, but I didn’t do any filming on those. It was actually just when I grabbed the camera – the three of us, me, Ines (Maria Ines Manchego, the DOP) and Mark Ball, our sound recordist – we would have learnt of a place we wanted to check out and we’d just kind of rock up and I’d start talking to them. I’ve used that approach for all my docos, or most of them – so it’s kind of my way of working rather than doing lots of research beforehand - but in this case we didn’t really have time. “

There were a number of very long days. “If you want an example, in the morning we’d be at a church filming musicians performing beautiful folk music and interviewing them, and then we met up with this swinging couple, because Sheffield has got the biggest swinging club in the whole of England, this place called ‘La Chambre’.

“So we went to this swinging couple’s house and it was big fluffy white shag-rag carpet, alcohol bottles, glass jars of lollies, kitsch. The cameraperson and I were having some drinks, getting to know them and just gauge whether we’d be able to use them for the film, and they asked me if I’d like anything else, and I said “a snake” - I meant one of the lollies from the jars – so the guy comes down from upstairs and drops this python in my lap. I’ve never held a snake before. I got teary-eyed. This incredible creature out of nowhere. You think you’re getting some Haribo lolly and then it comes to this. You got to experience quite a lot – I think what we got was quite concentrated.

"But none of that even got into the film. It was a little too tangential to the band. You have to be kind of disciplined when it comes to the edit, you need to stay quite focused.”

Late at night, he would get back to where he was staying and try to secure funding for a movie that hadn’t been paid for yet. Three nights before the concert, he was up Skyping the NZ Film Commission making a case for Pulp: A Movie About Life, Death and Supermarkets as a local project.

“Most of the people that made it – all the creative team – are Kiwi. So it’s quite a NZ production. My rationale was the money the Film Commission would invest in one short film that might play at a few festivals – they could put the same amount of money into this film and they would have a feature film with a guaranteed audience, with guaranteed distribution, they’d have a co-production with the UK, they’d be investing in talent. Maria Ines Manchego, the DOP, she’s a Kiwi; Peter O’Donahue, editor and cowriter – he’s a Kiwi – I’m a Kiwi and part of the concert crew filming – we had New Zealanders filming in that. So I personally thought there was a case to be made, but I totally get it – it’s not a New Zealand thing.”

He forged on, and some of the best moments that make it into the film are the pure serendipity in doing so. An ill-fated trip to see a Sheffield pub band play produced the wonderful Bomar, a young Pulp acolyte who bonded with his girlfriend over serial killers; a abandoned shoot involving an ice cream van discovered Liberty, a 10-year-old who threatens to steal virtually every scene she’s in. “It was pure chance. I was interviewing this couple who were getting their ice cream van ready – the woman had been unemployed and so her husband gave her this ice cream truck as a present so that they would have something to do during summer. I was filming them getting the truck set up when these kids walked past and were like “Hey, whatchu doing?” When kids see cameras, it’s like a magnet. I got a bit distracted for about an hour.”

Quieter but equally rewarding is the time Habicht gets with the group’s four other members, who always did more to make Pulp feel like a set of beautifully ordinary people. Other 90s British groups seemed like a row of identikit haircuts behind a charismatic frontman – Pulp had Candida Doyle, tiny and stoic; Steve Mackey, angular and art-school; Nick Banks, who looked like a stocky bouncer.

“Candida was very happy about it – I think they all really felt like Jarvis did get a lot of the limelight, originally, and so the whole process was quite novel. They were definitely all really into being in the film. Even Mark Webber, who people told me - you’re going to have a hard time filming him, he’s not very outgoing – but he was amazing.”

Banks, who comes across like someone who doesn’t care for chit-chat, actually warmed to Habicht fast. “When I met him backstage, Pulp had just done a gig in Paris – one of the first things he did was he pulled out his phone and he showed me photos of the soccer team that he coaches.” The film starts off with Banks’ daughter’s squad, resplendent in the group's logo the same way other teams might get sponsored by someone’s electrician uncle. “The other girls ask, what’s that?”, Banks quips. “Oh you know – just me Dad’s crap band. “

The good news for most New Zealanders (and anyone else who didn’t see Pulp on their reunion tour) is that the documentary isn’t too churlish to celebrate the final hometown show itself. With no dress rehearsal and no margin for error, it ends up being one of the best-shot live performances I’ve seen. Most big concerts feel like they have camera operators; this feels like a film crew. Habicht reveals to me that the DVD will come with a fuller edit of the night itself, though he indicates it’s customarily low on fanfare.

“The band themselves didn’t want to make a big deal of it. They didn’t consider it world news or anything. It was just a really long show. Three and a half hours long, to the point that the people at the venue actually put out the “Kick Pulp off the stage, now” call. They’d decided it was getting a bit annoying, and so some of their best songs got cut. My favourite song, ‘Dishes’ got cut from the setlist. They had an ice hockey demonstration tournament in there the next day.”

Habicht cops to feeling a little apprehensive about how the town would take the documentary ahead of its premiere. In the best possible sense, it’s a celebration of the mis-shapes and the misfits the group sang and stood for, but inevitably, another refrain rang in his mind. “Everybody hates a tourist”.

Instead, the film received a standing ovation in its subject city. “There were soccer teams and choirs, and just this teeming audience. From the choir who perform “Common People”, Sheffield Harmony. I had so many hugs from those ladies you wouldn’t believe it. Just a queue. I got a lot of love from the people who were in it.”

Jarvis warned him he’d be sick of their music by the end. And though Habicht freely admits he doesn’t get home and put on some Pulp as his first choice right now, the same band that gave him solace has ended up being a gateway to him. It’s hard to not to see how the film will raise his profile in the way his previous (very good) films couldn’t, and it marks a long road getting there.

“They formed in 1978,” he reflects. “They didn’t put out an album until 1983, then they didn’t take off until 1994. I always found that inspiring, because I’ve quite a few moments in my filmmaking career where I was a bit disappointed that I hadn’t made it to where I was hoping to when I’d started out and then I thought – “Oh, it took Pulp 15 years to get somewhere.””

Florian Habicht's Pulp: A Movie About Life, Death and Supermarkets is screening across the country now as part of the New Zealand International Film Festival.