Empires Unspooled and Rewound

On half-forgotten histories, kinship and the paradoxes of homeland. Divyaa Kumar on the strikingly impactful works in There Is No Other Home But This at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery telling stories of resilience and triumph.

There Is No Other Home But This is an exhibition primarily of textiles, rich and vibrant and full of tender love, and of artworks that draw from a textile history, concerned with a common origin born of migration, occupation, displacement and craft in the Indian subcontinent. Situated between the tiered levels throughout the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, it includes various textiles, embroideries, animations and mixed-media works. The two artists are Khadim Ali and Areez Katki, whose works are scaffolded by a dense and rich history – both ancestral and canonical – of textile practices, and they form a type of harmony, pulling from different strands of the historical cloth from which they’re both cut.

The two artists are Khadim Ali and Areez Katki, whose works are scaffolded by a dense and rich history

Stepping into the gallery feels a bit like entering a place of worship. There is the immediate sense of weightiness, of importance, of slowing down to listen carefully to what is being said. The spaces are slightly dim, the lights lowered just a touch, and you can hear a voice singing. There is a small plinth set up for Hijri, the Islamic New Year. The energy is more in line with homely worship, an altar on the mantel. It’s intimate and uplifting – joy as a form of reclamation, tenderness and defiance.

*******************

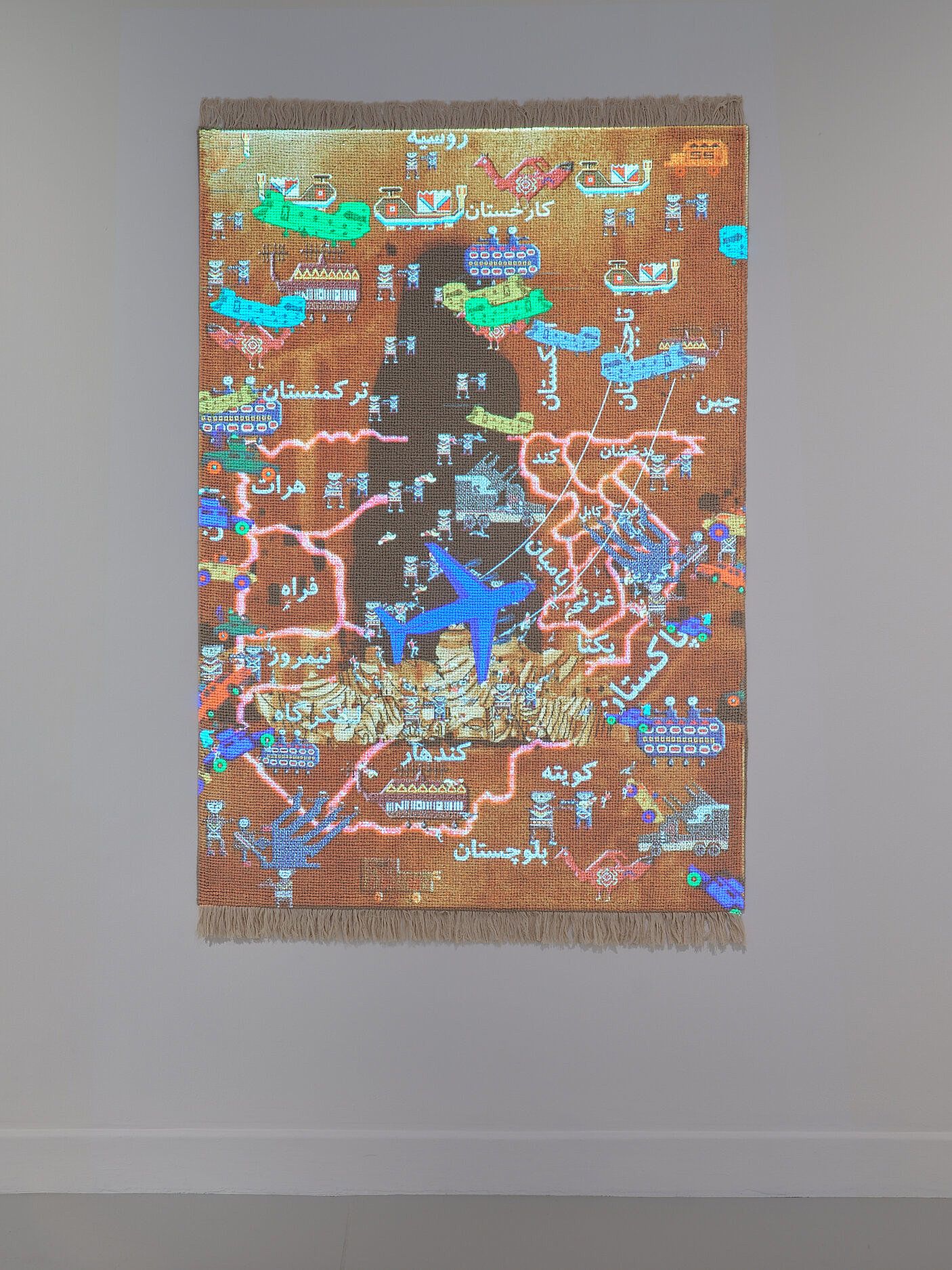

The first works you see are Ali’s rugs, hung up on the walls of the ground floor. Drawing from a complex tradition of Afghan war rugs, Ali’s works are grand in scale and abundantly rich in iconography, lifting shapes and symbols from his own lived experiences and modern news imagery, and pulling motifs from stories associated with Persian culture and history, most notably the epic poem Shahnameh (pronounced shaah-naah-meh) which translates to The Book of Kings (c.977–1010 CE), and the text The Conference of Birds (12th century). They are foundational texts that scaffold almost all of Ali’s works on display – it is his voice you hear singing as you come in, reciting the epic in the manner of his grandfather, who was a traditional performer of the poem.

Afghan war rugs, which serve as a launching pad for these works, rose to prominence as a souvenir item aimed at military personnel during the American and United Kingdom armed forces’ presence in the region

The rugs are strikingly impactful, showcasing drones, tanks, car bombs and wounded civilians, bordered in Farsi script and bandoliers of ammo. The colours are bold – deep bloody red and vibrant blues. Stylistically, they are confronting. These works point out a Western preoccupation with the so-called ‘trauma market’ – an aesthetic appeal that reflects a vicarious desire to consume the emotional landscape and experiences of refugees like souvenirs. Afghan war rugs, which serve as a launching pad for these works, rose to prominence as a souvenir item aimed at military personnel during the American and United Kingdom armed forces’ presence in the region, under the Bush and Blair administrations. Typically, those rugs express a commercialisation of trauma, Afghan artisans presenting a saleable version of the imagery of war, 9/11 towers and hand grenades, events and objects that represent the realities of the war in the imagination of the West. What Ali’s rugs show are the actual layered, lived experiences of these refugees (a collective of which Ali is a member) and the unpleasantness that comes with those unfolding histories, rather than our own ideas on victimhood. These works unpack notions of whose stories are being told, and by whom, and seizes ownership of those stories back for those they represent.

*******************

Anyone familiar with Katki’s practice will know of his embroideries, but we are occasionally forgetful of his resonant beadwork. On the ground floor and laid out on a narrow taupe table is a tableau of Katki’s bead weavings. They depict a visual inventory of stolen and reclaimed cultural ephemera from Persian society – fragments of pottery, a woman playing a stringed instrument, a jewelled necklace – from the perspective of a post-colonial observer. The ongoing series – titled Thieves' Market –is handwoven using a Zoroastrian beadwork technique called tōran, and presents a domestic sensibility through the framework of tapestry weaving against a gridded format. The technique was taught to Katki by his grandmother Thrity’s late best friend and neighbour, affectionately referred to as Aunt Dolly, and the Czech beads were inherited from Thrity, imbuing the work with a personal and intergenerational resonance.

The ongoing series – titled Thieves' Market –is handwoven using a Zoroastrian beadwork technique called tōran

Areez Katki, Thieves’ Market, 2020, Govett Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Deceptively simple, this project reveals complexities that reside in the objects represented in the limited scale and structure. Cropped and pixelated, they are a fractured representation of a culture that has been subject to rupture and theft from its Indigenous dominions across Persia, Turkey and India. As stated in the wall text (delightfully in Katki’s own words), these bead tapestries are “sentinels of memory, and like cloth, are holders of cultural richness and its loss”, putting into question the nature of ownership of cultural artefacts, and how dominant cultures and their institutions can produce systems of violence.

On the next level up, on display with Katki’s vibrant embroidered works that line the wall is a small collection of objects that informed his research. Another taupe table displays a series of watercolour drawings on paper, an arrangement intended to supplement our depth of understanding of Katki’s processes. Katki’s cloth embroideries are hung beside this tableau, and what is refreshing here is you can track the journey he made from these drawings to the final works. The shape of a hand, a particular curve or line, can be transposed in cotton thread within a corresponding composition, a colour combination or a particular pattern can be remixed before being studiously stitched in places. It’s illuminating and charming, being invited into the artist’s process.

Having his matrilineal family so clearly involved, front and centre, is so incredibly generous for us

Also on show is a silk tunic from the 19th century, decorated with traditional Parsi embroidery, and an aged notebook belonging to Katki’s mother, Yasmin, inviting us further into the depths of the histories that Katki is pulling from. As a stenographer, Yasmin had her own linguistic shorthand, and the notebook is full of her careful pencil marks. We can only see the first page, but it isn’t hard to make the connection between this meticulous lettering and Katki's own non-linear storytelling techniques, the bending of the shapes of letters and words into something else. Having his matrilineal family so clearly involved, front and centre, is so incredibly generous for us, and speaks of the kind of quiet worship we have for our loved ones.

The Zoroastrian faith is notoriously guarded, practised discreetly in the private homes of its followers, informed by a long history of persecution and forced migration

The emphasis placed upon this matriarchal weight is also a point of deliberate inversion. Katki hails from a family with deep roots in the Zoroastrian faith, which holds significance as one of the oldest monotheistic religions around today, predating Abrahamic religions. The Zoroastrian faith is notoriously guarded, practised discreetly in the private homes of its followers, informed by a long history of persecution and forced migration. It is also an intensely patriarchal faith, which makes Katki’s decisions to work in typically feminine crafts a vector of interest. The importance placed upon his maternal family in no way impedes the respect he has for his faith and origins, rather these investigations into textiles serve as a vehicle for a mediation of domestic relationships as well as the more domineering concepts he tackles.

*******************

Khadim Ali, Sermon on the Mount III, 2020, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Scale and its associated importance can often be a Western preoccupation; that the larger a work is, the more important it is. Katki’s textiles interact with that canon, as do Ali’s rug works, but are separate branches stemming from the same tree.

Prior to 2011, Ali worked in paintings, in the classical Mughal miniature style, which he studied at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan. Miniatures have a more practical justification for their size, being that they were used in domestic settings as vehicles for storytelling and memory keeping. Ali’s paintings hold the incredible level of detail, patience and dexterity that one would find in a miniature. You can clearly see each brush stroke, each fine layer, and understand that these works are laboured over with an immaculately sharp eye, a genuine love of the craft, and a level of ultimate dedication.

Ali’s scenes intertwine figures from historical Persian literature with contemporary geopolitical power players and the ordinary folk who suffer the consequences of bureaucratic machinations. Delicately pressed gold leaf illuminates the faces of American politicians, Persian-style goat-headed men and the mythical phoenix, graceful curving calligraphy and military drones. Each brush stroke is precise and carefully considered.

The transition from the intimate detail of these miniature paintings to imposingly large tapestries came in the terrifying form of a suicide bomber

The transition from the intimate detail of these miniature paintings to imposingly large tapestries came in the terrifying form of a suicide bomber, who in 2011 triggered an explosion outside Ali’s childhood home in Quetta, Pakistan, brutally injuring his parents and demolishing a majority of the residence. When he eventually reunited with his parents in Australia, Ali learnt the only things to have survived the vicious destruction were a few rugs, given to his mother by her mother, and likely her mother before her. It sparked a realisation in Ali of the resilience of the medium, to survive an act of terror, thus developing a new chapter in his artistic practice.

Ali learnt the only things to have survived the vicious destruction were a few rugs, given to his mother by her mother, and likely her mother before her. It sparked a realisation in Ali of the resilience of the medium, to survive an act of terror

The expanding of Ali’s practice in this manner provides avenues to interrogate scale even more deeply. On the top floor, standing in the shadows of these three grand new works, you become uniquely attuned to the great distances and trials these textiles have navigated, the histories they’ve witnessed, and the psychic threads that seem to pool around them. They resonate with an invisible aura that puts you on edge, vibrating in space, tugging you between abject sadness and determined joy. They are monumental in size – one of the tapestries is nine metres long – and are loaded with precise details we’ve come to expect. Bursting with colour and pattern, there is so much to look at you can’t get a handle on it all at one. An angel flies by holding a domestic fire extinguisher. A clown riding a lion brandishes an RPG gun on a velvet mountain-side. Children fly kites that look like attack drones and cargo planes. It's almost overwhelming, giving you little time to process, which is likely intentional. In the fog of war zones, there is little time to second guess or ponder the meaning of events taking place around you.

*******************

Ali’s rugs and tapestries are made collaboratively, hand woven and assembled in his studio in Dasht-e-Barchi, a settlement in western Kabul, and in the homes of Hazara men and women, each thread and patch of fabric touched by the hands of artisans who have since been violently dislocated. These three large tapestries have had a more tumultuous journey to Ngāmotu than they ought to have.

Ali was forced to organise two very high-stakes deals with a people trafficker, to leave the relative safety of Pakistan and cross into now Taliban-controlled Afghan territory, to rescue these artworks from the bus depot, and smuggle them back into Pakistan

When the United States officially left Afghanistan at the end of August 2021, they abandoned the country to the Taliban. This uprooted and cut the delicate fabric of Afghani society, displaced and made refugees of thousands of people. As the Taliban ripped through villages and cities, the artisans Ali had been working with had to abandon the tapestries to ensure their own survival, leaving the completed works in a Kandahar bus depot, disguised as cushions. Ali was forced to organise two very high-stakes deals with a people trafficker, to leave the relative safety of Pakistan and cross into now Taliban-controlled Afghan territory, to rescue these artworks from the bus depot, and smuggle them back into Pakistan to the artisans, and subsequently to Ali’s Australian studio. When they did arrive in the hands of the Hazari artisans, some 240 kilometres away, two of the three tapestries were damaged, cut into with knives and bayonets, the kind one might find strapped to the end of an AK-47. Artwork of all kinds is illegal under Taliban rule.

When they did arrive in the hands of the Hazari artisans, some 240 kilometres away, two of the three tapestries were damaged, cut into with knives and bayonets, the kind one might find strapped to the end of an AK-47. Artwork of all kinds is illegal under Taliban rule

The tapestries were repaired by Ali’s original assistants in Quetta, for whom he had secured safe passage, and were returned to their original imposing grandeur. If you look closely enough, you can feel the tender care gone into these works, the careful handling and rehandling that, even with the best intentions, leaves a sort of psychic wound on these rugs. Ali didn’t instruct these artisans to repair the works – this was done of their own volition. In taking agency over the material damages done to them, they have taken ownership over the violence that happened to them, and any potential viewership of that violence away from us. Even Ali didn’t get to see the works in their damaged state, as they were shipped from Pakistan to his Brisbane studio fully repaired and patched. Even unintentionally, these artisans point out our preoccupations with foreign traumas.

Khadim Ali, Feral Clowns, 2021, Those who were killed in the caves, 2021, Sermon on the Mount III, 2020. Installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

*******************

On the top floor of the gallery, Katki presents an impressive installation of new works, an exciting venture into sculptural installation that immediately makes the viewer feel they have stumbled upon the ruins of a razed archeological site. Persepolitan is a series of stacked adobe bricks – a centuries-old Persian technique of mixing clay and straw – along the centre of the room, five of which are wrapped in embroidered cotton-duck fabric and placed perpendicular to the rest, with a selection of Katki’s elegant embroidery works floating in the space above, suspended from the ceilings and walls in the gallery, hovering like startled birds frozen mid-flight. Katki notes in his ArtZone interview that “the ways in which the textiles are swooping and flying are akin to the murmuration of starlings across the sky, done – in one theory – to protect themselves and disorient a predatory gaze”.1

Here, Katki represents a Persian ruin through the experience of Persian heritage, and in his words, attempts “a repositioning away from colonial impositions

This predator is in fact us, the viewer, who cannot help but look at these works through our Western eyes, the lens we have been provided by our colonial education and societal fascination with foreign traumas. Our perspectives stem from Western interpretations of a Persian history, one that struggles to be shown authentically given that its archives were largely demolished by Alexander of Macedon in his destruction of the Persian capital of Persepolis (the namesake of this installation). Subsequently, any archival and archeological materials kept or discovered have been viewed through a Western colonial discourse. Here, Katki represents a Persian ruin through the experience of Persian heritage, and in his words, attempts “a repositioning away from colonial impositions … to speak of sovereignty and relationships to land that might occur by a gentle act of delineation of one’s heritage”.2

This arrangement of objects in space is directly informed and worked upon with the foundations built in Katki’s Persian heritage. The experience of the migration of the body and the religion to India, and subsequently Aotearoa, is present here as well. The adobe bricks were made in Whakatū, and are made of clay, mud and straw using the traditional Persian techniques. Here, stacked reminiscent of a ziggurat (a stepped pyramid structure often found across Persia) they become clean metaphorical objects conveying complex diasporic notions of belonging to a land, of whenua here and whenua gone, and whenua far away.

The embroidered markings on each parcel feature abstracted representations of women in Achaemenid art

The five wrapped bricks along the top of the arrangement are reminiscent of gifts, parcels of land one might offer to someone who is bereft of it. This notion of gifting land, of sharing and providing, has a clearly weightier value to someone of a migratory background who has experienced such devastating loss as being landless. The embroidered markings on each parcel feature abstracted representations of women in Achaemenid art – the Achaemenid dynasty ruled Persia from 553 to 330 BC – and are addressed to specific individuals: Aunty Dolly, grandmother Thrity, mother Yasmin, sister Delzin and himself. As Katki cleanly puts it: “Five individuals are now connected to a small block of earth, if only to hold, amid the disillusionment of migration, one’s own plot of portable terrain”.

Areez Katki, Persepolitan, 2021, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Areez Katki, Persepolitan, 2021, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

*******************

Touching on the concepts of the normalisation of war and the fragility of refugee migrant stories, there is another new work by Ali that blends again these ideas. Breaking into a new medium drawn from experiences in Covid-19 lockdowns in Australia, a digital animation is projected onto a carpet mounted on the gallery wall, depicting the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan by the Taliban in 2001, condensing weeks’ worth of burning, mining and dynamiting undertaken in the name of an iconoclastic campaign against an anti-Islamic Western influence. The Buddhas were located in the Valley of Bamiyan, an area in Central Afghanistan where the distinct ethnic group the Hazara resided – a culture Ali is a part of.

A digital animation is projected onto a carpet mounted on the gallery wall, depicting the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan by the Taliban

The animation is in the style of an 8-bit video game from the 80s, pulling clear stylistic motifs and sounds from the Atari console game WarGames. The mimicked pixelation of the game remarkably resembles the texture of a woven rug. The fake computer sounds of laser beams being fired are overlaid with Ali’s voice singing from the Shahnameh. Animated olive-coloured tanks and flat electric-blue drones fly over the crumbling Buddha and the void left behind; we eventually see CH-47 helicopters flying from the rubble, blocky figures of fleeing citizens, and a thick blue motif of a plane, like an in-flight map, with figures tumbling out mid-flight to the ground. As in the rugs and paintings that make up the majority of Ali’s past works, we don’t get to see the actual source of trauma, but rather impressions of it. Many of the motifs and shapes are pulled from the drawings of children, filtered through their gaze, and everything is filtered again through the animation style. It’s painfully raw, like an open wound left unattended, and witnessing this builds a deep ache in your chest.

Animated olive-coloured tanks and flat electric-blue drones fly over the crumbling Buddha and the void left behind

Khadim Ali, The War Rug, 2022, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Khadim Ali, The War Rug, 2022, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

*******************

There is No Other Home But This is a poignant exhibition with remarkable depth, a wellspring from which a reservoir of experiences is drawn. Despite the complex source materials – be that matrilineal worship or ethnic persecution – there is a palpable sense of celebration and joy in this show. It's in the carefully handled stenography notebook of Katki’s mother, in the pride of the delicately restored patches in Ali’s mammoth tapestries. It's in the carefully controlled ways you might look at these works that are so deeply considered, turned and mulled over. So much so that even with the ravaged subjects from which they stem, the solid foundations of joy in Persian history are present. There is no room for war porn here, either historical or current, and we don’t get to take it away and consume it like a souvenir – rather we join in on the celebration and pride in these histories and these people, and their hard-fought survival. And we do it on their terms.

1Dan Poynton, “Man of the Cloth: Interview with Areez Katki,” ArtZone 90,2022, 35.

2 Wall text, Persepolitan, in There Is No Other Home But This,Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Ngāmotu New Plymouth.

*

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Govett-Brewster. They cover the costs of paying our writers, while we retain all editorial control.

Feature image: Khadim Ali, Feral Clowns, 2021, Those who were killed in the caves, 2021, Sermon on the Mount III, 2020. Installation view, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Samuel Hartnett