The World’s First Lovers

Something new is brewing in Ōtepoti and Kāi Tahu theatre. Mya Morrison-Middleton responds to the ill-fated journey of a Māori wahine in 80's smoke-filled Ōtepoti, intersected with Tānemahuta and Hineahuone's love story.

Kāi Tahu, Waitaha writer and director Jessica Latton’s show The World’s First Lovers follows a Māori wahine in 1980s Ōtepoti as she is pulled from the destruction of racism, disconnection, addiction and ill-fated love through refinding her whakapapa origins within Hineahuone. This work has the potential to become a defining piece of Ōtepoti and Kāi Tahu theatre.

To tell a story so particular to the south, it’s important to unpack the place in which this work is set and shown. Ōtepoti Dunedin is within Kāi Tahu’s large takiwā and is a port and university city, with visiting rural populations from nearby. Kāi Tahu have a long and complex history with tākata pora, who arrived early in the settlement process as whalers and sealers. Scottish settlers prided it as the Edinburgh of the south, and overlaid the town plans for the capital of Scotland on the distinctly hilly and swampy whenua. As this work uncovers, Ōtepoti has struggled through its own Trainspotting era.

Ōtepoti has struggled through its own Trainspotting era

The show is presented as a “homage to Hineahuone, the world’s first woman crafted by Tānemahuta.” The poster shows Tānemahuta and Hineahuone in embrace, and the title, The World’s First Lovers, gave me the impression that I was walking into their love story. I quickly realised that was not what I had stepped into. Tānemahuta and Hineahuone are spliced in (along with a bigger creation story) as a dramatic device. The pair share one affectionate scene with almost no dialogue. Instead, the work focuses around a central protagonist, Fortune, moving through the trials and awakenings of being both a woman and Māori in Ōtepoti during the 1980s.

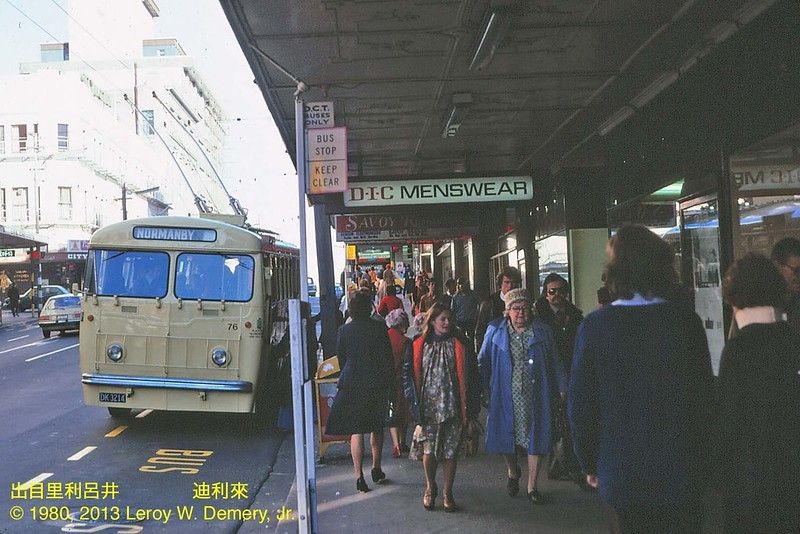

Princes St at Moray Pl, Dunedin, 1980 (Photo credits: Leroy W. Demery, Jr/Flickr)

Atua pūrākau and creation frameworks are used as a dramatic device to explore transformation. The punctuating moments with atua cleverly and gently mirror the journey of Fortune’s life. Celestial Aoraki and Tānemahuta share a moment of unifying brotherhood – “we’re brothers. There are no half brothers” – a contradiction of Fortune’s description of her fractured family unit. The creation of Hineahuone by Tānemahuta, and their meeting, parallels Fortune’s destructive relationship and deteriorating mental health. The show opens with a message, “You are all gods”, setting up the central idea that to live well we must remember we descend from atua – because disconnecting from whakapapa, recent and metaphysical, has severe effects. After she is created, Hineahuone implores: “If you forget me, you will forget who you are. Remember my name.” Using pūrākau as a narrative device, or framework for performance, is becoming common in Māori theatre. These works could form a genre in their own right, characterised by atua appearing as characters within a work, pūrākau framing the piece, or atua as an allegory.

Using pūrākau as a narrative device, or framework for performance, is becoming common in Māori theatre

This work offers a cathartic process for Māori raised in Te Waipounamu, which I assume could resonate more for generations who lived through the 1980s. I tread carefully into storytelling about trauma as it can overwhelm me. I need to laugh, and to hear all the other experiences beyond trauma that make us three-dimensional people. But the reality is that all of these stories can, and should, be told simultaneously to describe a holistic world of being Māori. The atua in this work allow it to tell a difficult and familiar Māori story without further scarring the audience. Pūrākau are growing in usage across many disciplines, even as a treatment method in mental-health care, by people such as Dr Diana and Mark Kopua. There are confronting moments of violence, racism and mental distress within the work, but these aren’t dwelled upon. During a haunting mental breakdown, a narrator calls out, “Psychosis or matakite. A blessing or a curse.” Taoka pūoro, waiata and characters changing into atua provide relief and bring us out of the heaviness, reaffirming that live performance is a potent and transformational medium. By using sensory processes like ihi, wehi and wana, and the unity and release of waiata, we are able to feel all of these experiences. Rather than keeping them to rot within us, we exhale them out in our next breath.

Photo credits: Kassandra Lynne

By using sensory processes like ihi, wehi and wana, and the unity and release of waiata, we are able to feel all of these experiences. Rather than keeping them to rot within us, we exhale them out in our next breath.

There was great theatre craft within this production. The lighting design by Martyn Roberts sublimely recreated the pink-lit 80s clubs. Ben Whitaker supported with a responsive taoka pūoro score. Manu Syme-Hepi, the youngest cast member, performed an impressive rotation of roles with presence and ease. Syme-Hepi and Nick Tipa gave energetic performances of cataclysmic creation moments, with Dragon Ball Z-style kāmehameha attacks, but with a twist of tīhei mauri ora! The cast worked well with quick scene-changes, a bare set and a runway-like performance space had them constantly walking forwards and backwards – ka mua, ka muri. At times it was hard to follow where in time a scene had jumped to, especially with cast members playing multiple people, deities and narrators. This lack of clarity didn’t overshadow the quality of the work, and I anticipate these finer delivery details will get sharper in the play’s premiere season.

...energetic performances of cataclysmic creation moments, with Dragon Ball Z-style kāmehameha attacks, but with a twist of tīhei mauri ora!

The script is a consistent merit of the work. As Latton’s debut full-length written play, the story has been developed extensively through programmes, festivals and residencies. This development and research time is clear in the detail of the script. One example is the extensive descriptions of Hineahuone’s creation, impressively the many atua who gifted the intricate parts of her genitals are named. The dialogue is poetic, including lines revealing that Fortune’s marae is at Rāpaki, on Te Pātaka-o-Rākaihautū Banks Peninsula:

“Rāpaki is as real as a mountain."

“There are taniwha in the harbour. Takaroa take us home.”

Latton’s poetic and descriptive language elevates the script and creates an immersive, distinctively Ōtepoti wairua within the theatre. The script cuts between vignettes of cruel kids who sell possum skins at school, skinheads in Caversham and punks in cold mansions. A disturbing favourite was the description of living in exile in a haunted house surrounded by paddocks, swamps and dog shit, where a kaumātua is paid $5 and a packet of cigarettes to clear out a ghost.

a haunted house surrounded by paddocks, swamps and dog shit, where a kaumātua is paid $5 and a packet of cigarettes to clear out a ghost

The layers of ahurea Kāi Tahu in this work add a complexity I want to see live performance keep moving into. The Kāi Tahu creation whakapapa shared covered the web of relationships between Pokoharuatepō and Rakinui (which birthed Aoraki), and the love triangle between Takaroa, Papatūānuku and Rakinui (the latter two who birthed Tānemahuta). I was absorbed, wondering how and which whakapapa would be recited. The only other time I’ve felt a similar Kāi Tahu-specific creation excitement in a performance was Rua McCallum’s Wairua (2021). The script is supported by seamless use of Kāi Tahu mita, replacing ‘ng’ with ‘k’. Another highlight was fellow Kāi Tahu designer Amber Bridgman’s costuming. I spied a kākahu, potentially made from neinei, on Hineahuone and admired the understated details of mahi toi Māori in the costuming for the rest of the cast. The piece closed with the uplifting waiata ‘Ka haea te ata’, with the final lines declaring that as mokopuna of Tahupōtiki we settle here. This work represents a direction in which theatre should be moving, towards Māori-led and performed works, telling iwi stories, within our rohe.

the piece closed with the uplifting waiata ‘Ka haea te ata’, with the final lines declaring that as mokopuna of Tahupōtiki we settle here

My lasting sentiment is that, for Māori living in Ōtepoti, and wider Te Waipounamu, works like The World’s First Lovers are essential. A core part of tikanga Māori is acknowledgement. We mihi to the whare, to the dead, and we chant whakapapa to keep focus through karakia. Have all Māori wāhine in Te Waipounamu lived versions of the same life? In a rural schoolyard-scene a young boy mocks Fortune crudely about blood quantum: “Are you a half? Or a quarter? An eighth? Or what are you, a 32th?” (pronounced as “thirty two-th”). This moment, among others within the work, has been lived by many in Te Waipounamu but, until recently, has not been a big part of our local cultural conversations. As the play ended, I wanted to crawl back into smoke-hazed 80s Ōtepoti, into the family kitchen where Fortune’s mother is urging her to forget Māoritaka including “the old gods” and back into the velvet embrace of Hinenuitepō. I understand this desire as the same reason I poke bruises or pick scabs. To examine injuries and to witness them. This timely work witnesses the experiences of Māori wāhine, and calls for our restoration as the descendants of atua in Ōtepoti and beyond.

I washed my hands to whakanoa as I left the show, and thought of all the other people who need to witness this Ōtepoti, and Kāi Tahu, story.

Photo credits: Kassandra Lynne

The World’s First Lovers Development Season

7–10 December 2022

Allen Hall Theatre, Ōtepoti

SECOND SEASON ANNOUNCED:

The World's First Lovers

13 – 17 June 2023

BATS Theatre, Te Whanganui-a-Tara

Programmed as part of Kia Mau Festival