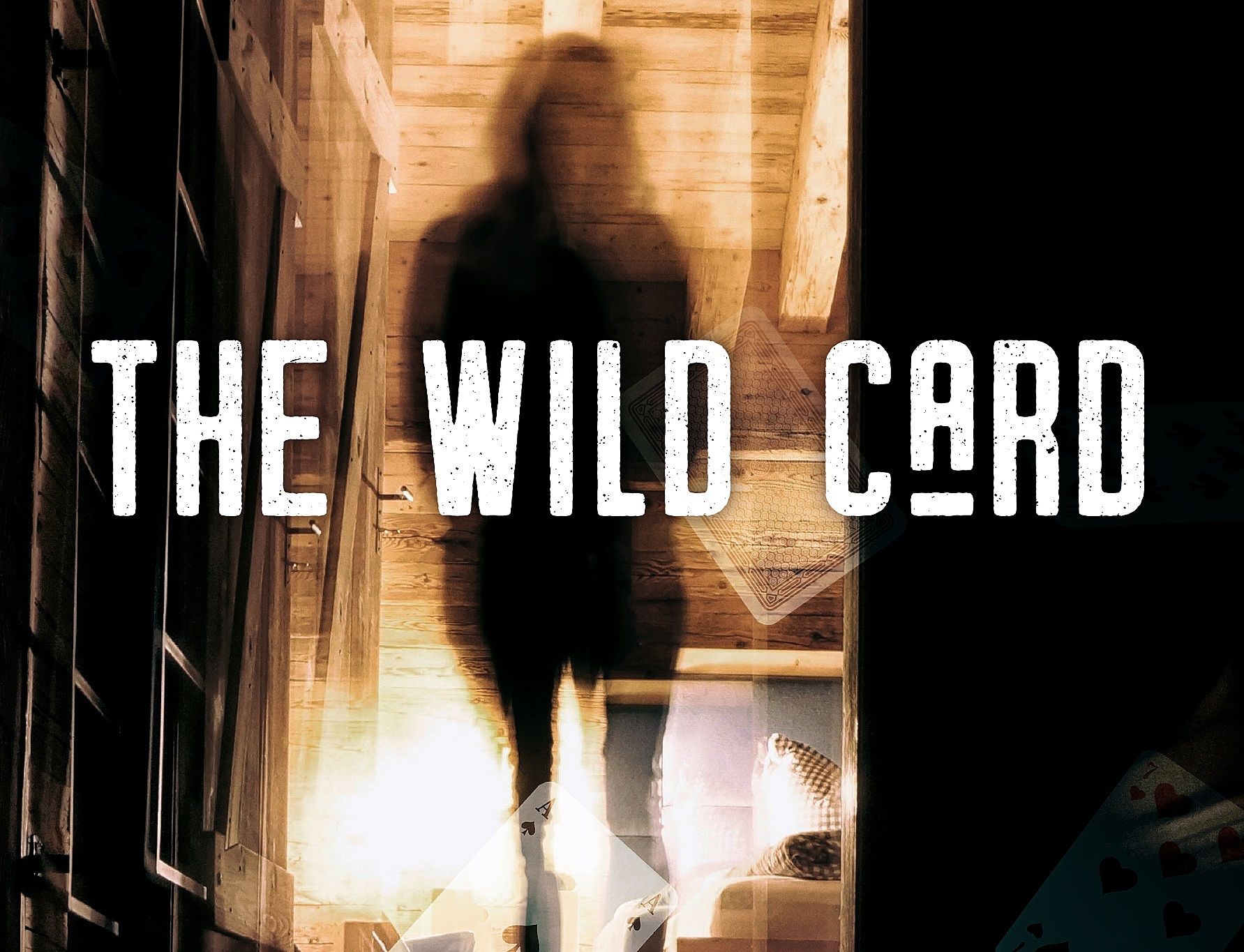

Wild Ride: A Review of the Wild Card by Renée

Kaupapa Māori Editor Ataria Sharman reviews Renée’s latest novel about child abuse in state care, The Wild Card

Kaupapa Māori Editor Ataria Sharman reviews Renée’s latest novel about child abuse in state care, The Wild Card.

The main character in crime novel The Wild Card by Renée (Ngāti Kahungungu) is no damsel-in-distress. She’s a theatre-stealing, boss ass wahine toa determined to solve the mystery of her friend’s death, even at risk to her own life. In a literary landscape often devoid of strong female characters, 30-something Ruby Palmer, from the imagined town of Porohiwi is tough, courageous and endearing to the reader.

In search of answers to the death of her friend, The Wild Card opens with Ruby’s exploration of the children’s home she grew up in and ends with a vicious attack by a balaclava-clad man. Throughout the novel, the decisions that Ruby makes demonstrate her mettle and strength, a strength that is personified in the women who support her.

Setting and storyline allude to the heart of Renée’s novel, that is “the story of Māori children put into state care and abused in the institutions that were supposed to care for them”. Through character dialogue we are told that Ruby was abandoned as a baby and found cocooned in a kete on the doorstep of the The Porohiwi Home for Children. Overt institutional racism is highlighted in Ruby’s recollection of the Matron giving all arrivals to the Home a new name, because their Māori ones were not palatable for her to pronounce. Then as she delves further into her childhood, it becomes clear to Ruby that her teenage friend Betty was the only one standing between being sexually abused in the home and her seven-year-old self. That was, until Betty’s dead and sodden body was found by the lake.

The Wild Card is set in the bicultural climate of many of New Zealand’s small towns, and yet the characters aren't introduced as Pākehā or Māori, or given brown or pale skin. Instead, cultural differences are made evident through the way the characters act and how they hold themselves.

Betty’s notebook is bequeathed to Ruby, containing only a series of symbols from a pack of cards; the diamond, spade, heart and clubs. Cards and their symbols continue to reappear, in Oscar and Ruby’s relationship, a card-themed party, and the mysterious card-games that took place in the now-abandoned Children’s Home. Now in her thirties, Ruby begins to piece together the puzzle of her friend’s death. Thus, the mystery begins.

The Wild Card is set in the bicultural climate of many of New Zealand’s small towns, and yet the characters aren’t introduced as Pākehā or Māori, or given brown or pale skin. Instead, cultural differences are made evident through the way the characters act and how they hold themselves. For example when Polly, “Auntie Polly” storms unannounced to Ruby’s office with her niece and a cake in tow. The assertion she is “Auntie Polly”, even though Ruby has never called her that before and the act of bringing along whānau and kai to share suggests to me that she is Māori. Then there is Auntie Polly’s no-nonsense manner that leaves “every possibility that Polly could have taken on the entire Māori Battalion and made them back off”, reminding the reader of many a wahine toa who cannot be tamed.

Bicultural nuance in this novel is made accessible because the author is Māori and Pākehā. For example, the depth of the relationship shown between Kate and her best friend Kristina is shown when Kristina calls her “fucking hori”, in a way that is neither derogatory nor racist. It reads rather as an inside joke between the two women.

The small-town of Porohiwi is located somewhere between Palmerston North and Wellington and provides the setting for the characters and storyline to unfold. It has a local theatre called The Swan that is “home of the Porohiwi Players”, the Segar family home, Children's Home and Meg’s (Ruby's grandmother’s) house with an overgrown garden that is full of surprises.

Character building is strong, and there are a lot of them too. Small-town communities and their creativity are highlighted, with lengthy dialogue in theatre troupe meetings, and a spotlight shone on the struggles of locally owned newspaper The Star.

Another clue to the novel’s commentary on biculturalism is Ruby’s relationship with love interest Oscar, a Dutch person. Comparisons are made between his privileged and comfortable life, and Ruby’s. Oscar is a sometimes-clueless Pākehā man with an adorable dog Karl, who, 14-years-ago listened to his mother instead of Ruby and ruined their fledgling marriage. As someone who has experienced her fair share of mother-in-law issues, this relationship had me tearing at my hair. Through the page, I could feel the love between the two, but also the cultural and racial tensions keeping them apart.

Oscar supports Ruby, but he doesn’t dominate the story. He’s present, but really, it’s all about Ruby and the women around her: Betty, her adopted mother Kate, best friend Kristina and grandmother Meg.

There is a reference to the acceptance of takatāpui before the imported teachings of the missionaries and a dramatic and soap-worthy range of relationships that challenge heteronormative conventions and establish a new-normal in fiction novels.

Feminism is a strong and overt theme throughout the novel, with a teenage Ruby exclaiming to Oscar at the school dance that she’s reading The Female Eunuch and “I’m a feminist”. You won't find stereotyped and overdone female caricatures like the housewife, gold digger or angry feminist in this novel. I would argue that there are no stereotypes at all, just real people and real characters.

There is a reference to the acceptance of takatāpui before the imported teachings of the missionaries and a dramatic and soap-worthy range of relationships that challenge heteronormative conventions and establish a new-normal in fiction novels. Ruby’s mother Kate is in a lesbian relationship with her partner, Daisy. Then there’s Marlon, the man used to trick the narrow-minded adoption agencies – “you’d have more chance of getting permission to adopt her if you’re a married woman” – into allowing Kate adopt the wild Ruby.

There were a couple of things I would’ve liked to see in this novel. More of Oscar grovelling when he finally apologises (this feels like it would’ve been really satisfying, though maybe Ruby is a better woman than I am), and a greater depth of backstory on the antagonists and their balaclava-wearing decrepit and wrong ways.

Having the opportunity to review this book by 90-year-old literary legend Renée, is a privilege so take everything that's been said here as a grain of salt and make up your own mind as you delve into the mysteries of Porohiwi and its energetic and varied inhabitants.

The Wild Card is published by The Cuba Press (October 2019)