The Wellington Boys’ Institute: A Charitable Instrument of War

Paul Gallagher trawls through the archives to bring us small slices of New Zealand history. This month, The Wellington Boys' Institute: charitable institution, instrument of war.

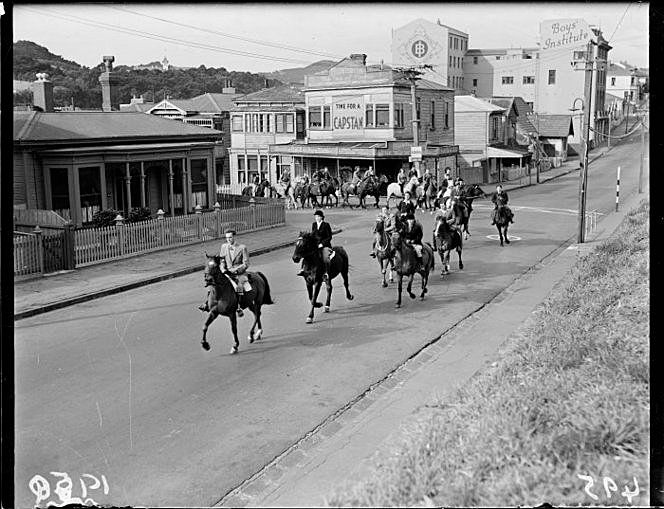

For the five years I've lived in Wellington there's been a large, bare section along Tasman Street, near the Massey University campus – an expanse of gravel, grass and clay ready in a primed state for development and fenced off to prevent intrusion. In the south-west corner of the earthworks stands the remnants of what was once the Wellington Boys’ Institute and S.A. Rhodes Home for Boys. It’s a site that heralds no great reaction from anyone – Tasman Street is largely a student thoroughfare for those walking between the central city and Newtown, and a main pedestrian route for those wanting McDonald’s from Adelaide Road.

What remains of the building is miserable in its dereliction. It once was a major complex, a charitable establishment that contained a pool facility, a gymnasium, workshops, a hall and a boarding home. It now stands boarded up, paint peeling, flashing warped, windows broken in places. It is a broken building, a shell of its former self. Its locks show the wear of would-be thieves or trespassers, and its walls are adorned with mouthy graffiti and obscenity.

When the Boys’ Institute was founded in 1883 it was associated with St John’s Church and had a fairly ambiguous brief: to benefit young people in the community. It took three decades for the Boys’ Institute and S.A. Rhodes Home for Boys facility to be built along Tasman Street. The foundation stone was laid by the Earl of Liverpool - Arthur William de Brito Savile Foljambe - who was at the time His Majesty’s Governor of New Zealand and who later would become the first Governor General of New Zealand in 1917. He performed his duty as a public figure (according to the scribed text of the plaque still on the front of the building) ‘to the glory of god’ on November 18th 1914. His speech on the occasion foreshadowed the ominous connection the Boys’ Institute would have with the military. He told the crowd that ‘at this time the Empire is in need of all of its young men’ and that ‘for the education of this country the Institute was prepared to lend a hand in this time of stress.’

A graduate of Sandhurst, the Earl of Liverpool didn't always sit well with politicians of the colony. Some regarded him as having an exalted sense of self importance. But his opening of the Boy’s Institute stands in importance for a number of reasons. First, his visit was akin to having the Prime Minister open a new school or hospital today. It served to provide higher profile and PR for the organisation, and to give them exposure in the public eye. Second, he had status. He was a uniformed officer and serving veteran of the Second Boer War: New Zealand’s first major foray into foreign affairs.

The rising tensions in Europe were such that by 1914 there were already indications of the hell that would be unleashed. The First World War had been underway since July and in the same month that the Boys’ Institute foundation stone was laid, the term ‘First World War’ was used. New Zealand troops had already taken German Samoa in their first hostile acts of the confrontation, and the spectre of a world conflict - on a scale never seen before - had taken a massive place in the public consciousness.

The Earl was the King’s man, a military man, the Empire’s greatest servant in New Zealand at the outset of the First World War – and his presence at the opening of the Boys’ Institute served a purpose, certainly suggestive if not explicit, in delivering a resolution. His was a righteous agenda, as the war was upheld – just as the opening of the Boys’ Institute was - in the glory of god.

Only a few months after opening the Boys’ Institute, the Earl of Liverpool’s name would be given to one of the country’s largest military units – the New Zealand Rifle Brigade (Earl of Liverpool's Own). This unit would later fight in Egypt and on the Western Front under the motto Soyes Ferme (Be Firm), with its battle honours including the Somme, Passchendaele, Messines and Le Quesnoy. But what of this man’s influence on the youth of the Boys’ Institute?

What makes the Institute unique is its location: its proximity to the grand residence of the Governor General. Sitting on sprawling luxurious grounds, it was completed in 1910 – four years before the charitable organisation opened its doors to the needy on nearby Tasman Street. The two buildings sit within a few hundred metres from each other. Government House occupies a substantial part of the view from the pavement outside the Boys’ Institute, and – presumably – the Earl of Liverpool, standing in the lavish upstairs bedrooms of Government House, would have been able to see the comings and goings of the boys from their facility.

The Institute also sits just two hundred metres from the National War Memorial – a site of remembrance and mourning dedicated in 1932 when the boys’ home was in full flight. It’s where the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior lies representing so many New Zealand soldiers who left to fight and find adventure in so many foreign battlefields, but who never made it home. Its construction also served as continuity between both world wars for the boys to observe, little more than a stone’s throw from where they were.

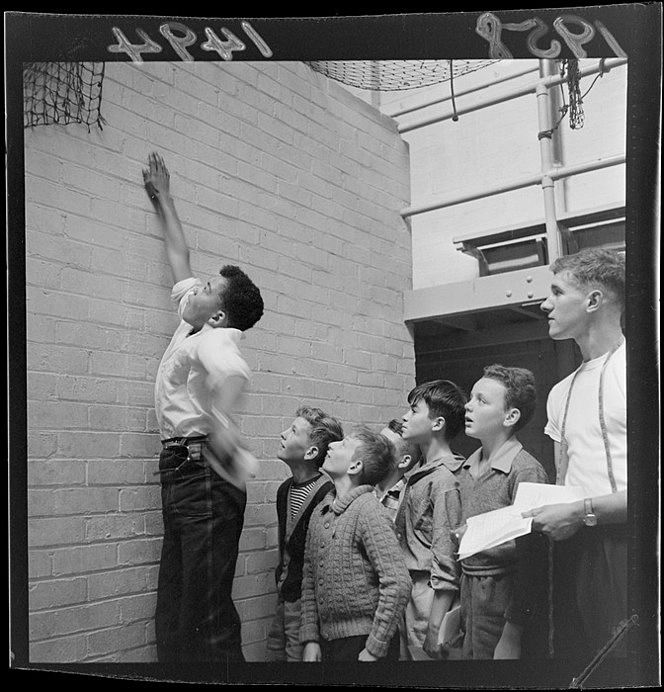

But what about the impact of living at the Boys Institute? The regimentation of youth is nothing new to anyone aware of the Boy Scouts or Girl Guides. But New Zealand’s boarding homes, set up mainly by charitable religious organisations, are often overlooked as forces through which ideals and dominant beliefs were instilled on parts of society where such influences were seen as lacking – orphans, the poor, and the disadvantaged.

There have long been connections and criticisms of other social youth groups for acting as gateway training organisations for the military. The Boy Scouts – set up by Lord Baden Powell – were long criticized as being too militaristic, with its military-style uniforms, badges of rank, flag ceremonies, and brass bands. But the Boys’ Institute was something else. Not everyone had access to resources or money to participate in the same sort of activities. But just as charity and welfare acts as a safety net to ensure that no one is ignored, the Boys’ Institute acted as a hand up or a drag net to ensure that indoctrination and militarisation reached all corners of society. No one was left behind.

It was something blatantly reflected in the speech of Hon. A. L. Herdman – then Minister of Justice in William Massey’s Cabinet – on the day of the Boys’ Institute’s opening. He spoke in glowing terms of what he called the magnificent display of manliness which our race was witnessing on the Continent of Europe. It was his opinion that the soldier fought not because he anticipated some personal reward, but because centuries of great deeds and centuries of great struggle had taught him that it was manly to fight for the traditions of his country and for an opinion that stands for what is best in the world. Certainly it was an obliquely misanthropic message to deliver to the boys – that essentially their godliness, their duty and honour would come through matching the sacrifices of those in the Great War. Indeed, Wellington’s Mayor of the time Mr J. P. Luke used his moment in front of the cheering throng to assure them he could see the Boys’ Institute bringing all sorts of good ‘not only to the city of Wellington but to the British Empire.’

It was a level of profile that continued for decades to come. The Boys’ Institute was visited by a revolving troupe of public figures and politicians. Sir Bernard Freyberg’s visit in 1950 was typical of such occasions. He was a rumoured participant of the Mexican Revolution under Pancho Villa and a veteran of the First and Second World Wars. A Victoria Cross recipient, he fought at such revered places of New Zealand’s military history as Gallipoli, Crete, and El Alamein. He became New Zealand’s seventh Governor General in 1946, and it was in this capacity that he visited the Boys’ Institute: a glowingly revered war hero and a long distance swimmer set as an example for all.

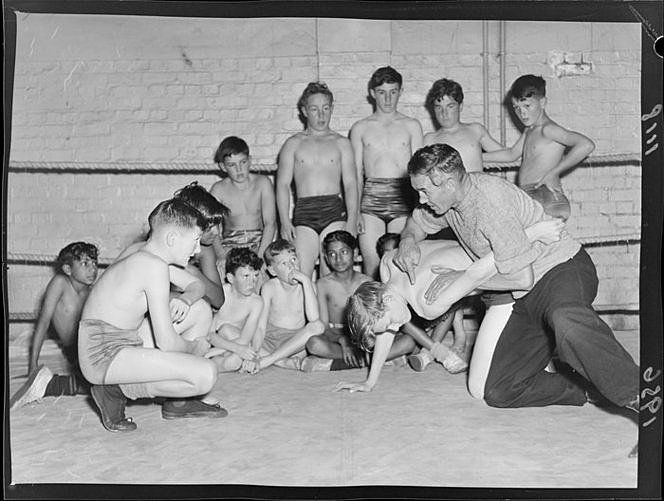

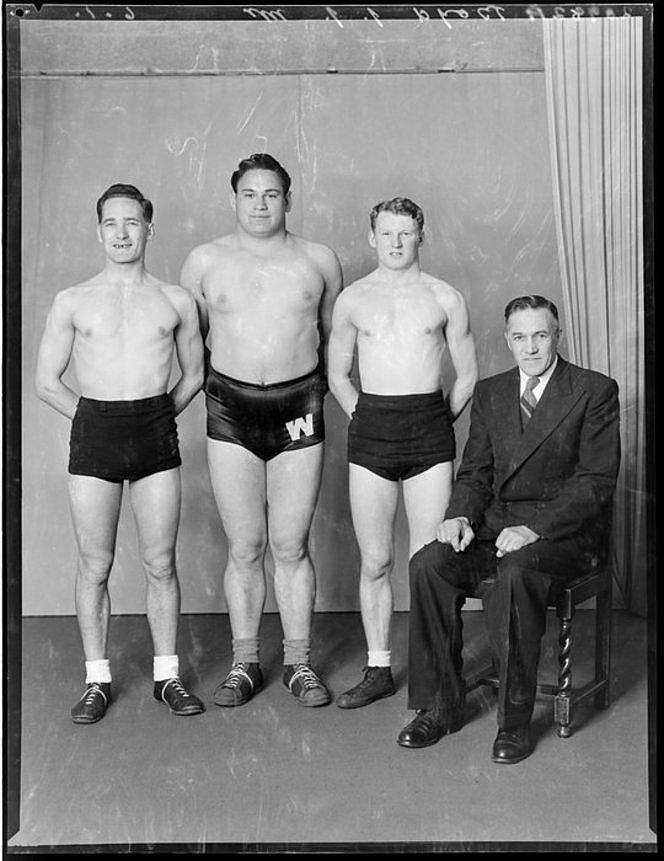

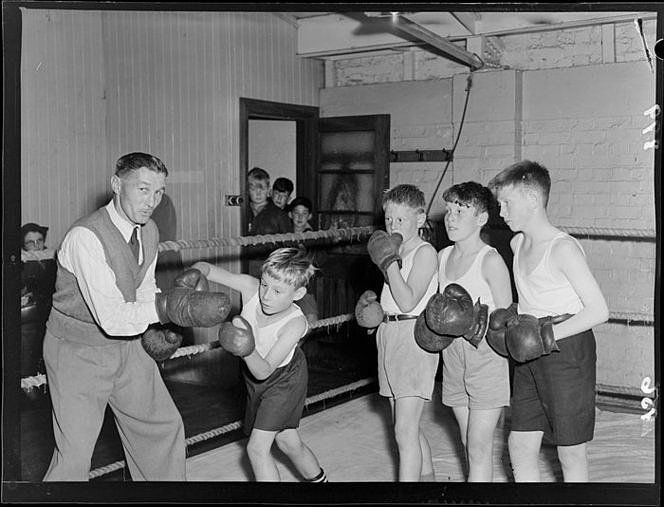

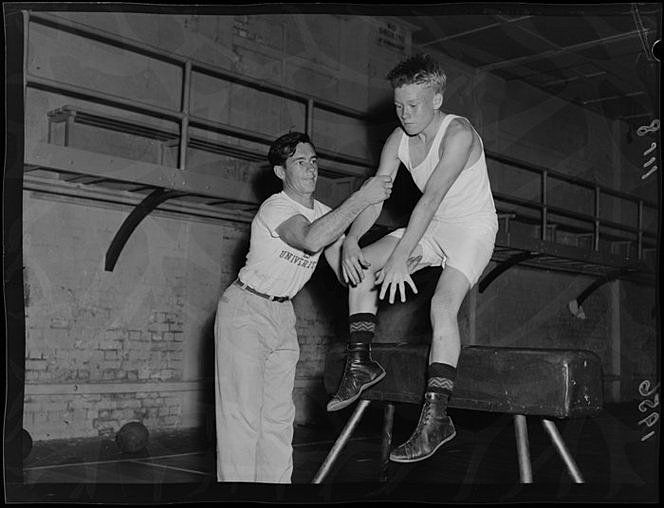

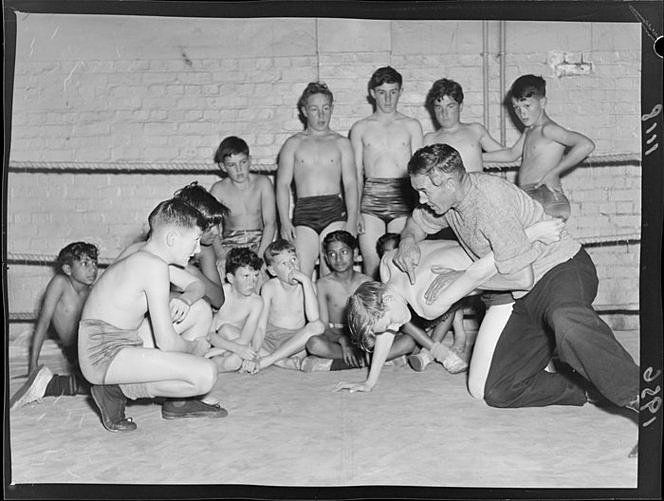

The Boys’ Institute sat squarely in the public eye. The Evening Post ran regular updates on the progress of fundraising for various expansions of the facilities, and the performances of the centre’s band at public events and sports scores of the various teams that competed in local competitions. The newspaper’s photographers were on site to record the progress and competition. The boys themselves were subject to visits from notable athletes who arrived with fanfare to the Tasman Street gymnasium. Johnny Leckie, the great force of New Zealand boxing during the 1930s, was one who arrived to offer his skills to the Boys’ Institute. His reputation was used as a model for the boys, and an inspiration to continue striving for more. Upon coming of age, many of them joined the military for service in both the First and Second World Wars – and those that didn’t served to support the war effort, both practically in terms of their service and ideologically for what they represented and what they were seen to represent.

Members of the Boys’ Institute were essentially made uniformed men at the outbreak of war. The resident band was co-opted into the Home Army to perform at war drives and parades. That worked to give the boys a taste of service, a sense of self-importance, and an active part in the wider militarisation of the community. How could society ignore the service, the military, the war, the duty to one’s country, if the community’s most disadvantaged were doing their bit for the cause – both at home and abroad?

The Boys’ Institute acted as a billboard of sorts, showing the community that through honest virtue and good living people could overcome disadvantage and find honour, service and even distinction. It served as a reminder to everyone else that service was not something avoidable, or to turn a blind eye towards. But the problem was that it may not have served to create little princes in the vein of Machiavelli’s virtu and fortuna, but instead worked to provide the Pied Piper’s tune to follow - and influence others to follow - into the dark cave of continental destruction.

It was a charitable organisation, yes, and one with good intentions, but the Boys’ Institute was also a subsumed ideological tool that highlighted the church hierarchy in civil society and its connection with the authorities within political and military constructs. There is no better example of this than the Evening Post in December 20 1939, where the speech of the chairman of the management committee, Mr J.D. Howitt, at the Boys’ Institute Christmas dinner function was recorded. He reminded the boys that the debt they owed the institute could be repaid by putting into practice throughout their lives the lessons of unselfishness and clean living which were instilled onto them while living at the building. The address of the Boys’ Institute director, Mr B.A. Mabin, informed the boys that their boyhoods were fast coming to an end and they needed to take advantage of the opportunity because from the outset of their manhood they would be expected to shoulder responsibilities in a world changing out of all recognition. The old order was passing, and the boys had to equip themselves for the new. Following the dinner (provided by the ladies auxiliary) the evening ended with the singing of the national anthem. In later newspaper articles, there would be discussion of how best to memorialise the service of those members of the Boys’ Institute who had fought and died on the battlefields of the Second World War.

It is a way of life not exactly depicted in the nation-building historical narratives of New Zealand’s academic account. The Boys’ Institute was turned into something more than private, not quite public, but a shared space of social exchange not entirely concealed from the community’s general view. It was, in essence, an assumed debt and an engineered social contract for the inhabitants: the obligation of allegiance and honour through charity. These lives were lived subject to a cause, at an institution in the public gaze. The Boys’ Institute acted to uphold the standards of society at the time, to instil the expected virtues of honour, and to encourage self-sacrifice and healthy competition. But considering the quasi-militarisation of the home and the World Wars that many of them undoubtedly went on to fight – and die – through, we might pause to consider the cost of engineering such lives.

Government House and the National War Memorial are obviously considered historically important and both enjoy heritage listings which mean their facilities aren’t left to fall into disrepair. The Governor General’s home underwent extensive renovations recently worth some $44-million.

The carillon of the National War Memorial is undergoing major structural work at the moment, sheathed in scaffolding, as work is undertaken to preserve the structural integrity of the symbol of our nation’s military sacrifices. It’s considered a sacred site, and is visited by around twenty thousand visitors each year – including the dignitaries that once would have attended the Boys’ Institute.

Such a memorial is certainly not the reality for the Boys’ Institute. The ground it once occupied is awaiting development of yet another major apartment building. It stands abandoned, mostly destroyed and ruined beyond use. It’s an anti-memorial, ignored by all and considered a blemish in modern terms. It seems easy to disregard, considering the politicians, community leaders and the Empire of old got what they needed.

NOTE: All of the photographs come from the archives of the Evening Post Newspaper, found at the National Archives in Wellington.