The Vision Does Not Stop Here: The Factory’s International Dream

For a musical that seems certain to meet international success, The Factory was born out of discontent, frustration, and a twenty-something year dream. Ahead of their Edinburgh season, James Wenley examines their long evolution.

At the Vodafone Events Centre in South Auckland earlier this month, it felt like a movement and a moment had arrived. Kila Kokonut Krew’s The Factory, the world’s first Pasifika musical, was performing their last New Zealand season before heading to Australia and then on to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The show was triumphant, and its development forms a feel-good story about Pasifika and New Zealand theatre, but creator Vela Manusaute takes pains to point out that they didn’t just arrive on the international scene. For a show that seems certain to meet international success, it was born out of discontent, frustration, and a twenty-something year dream.

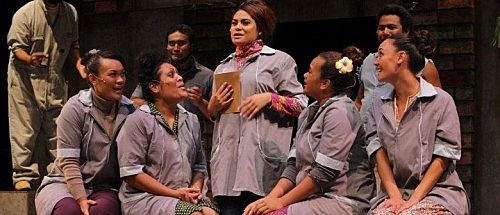

For those who have followed The Factory’s seasons over the last four years, you get the impression of a very fraught creative birth, with radical dramaturgical changes made in each version. I’ll never forget my very first Factory experience: travelling to the Mangere Arts Centre in 2011 to see the final week of a show that had been packing in houses for a month. I was excited and astounded: here was musical theatre of the Pacific; catchy songs and tight harmonies, and it had something very meaningful to say. The core of The Factory is cross-cultural immigration story: a Samoan father and his daughter come to work in New Zealand – land of milk and honey – to support their family back home. They’re accepted by their fellow workers from the Pacific diaspora, but they’re oppressed by the system and factory owner. It is a story of coming to a new land and the struggle to retain your roots. It is a story of rights and equality. The Factory ends with a message of hope and better lives; as the next generation step forward to make a change, as they sing: “The Vision does not stop here… this place is just a stop on our way home.”

I’ve never managed to shake that song from the playlist in my head. The 2011 show might have been rough around the edges, but its big songs were already hits, and the show’s soul, which can’t be faked, made a big impression. The cast made an appearance with a medley at that year’s Hackman Theatre Awards, and I was overjoyed when I randomly flicked one late night to TV-One to find a highlights package screening of the show. Other than this, The Factory remained a happy Mangere memory, until 2013 when the big announcement came that Auckland’s theatre community were hoping for: The Factory was headlining the 2013 Auckland Arts Festival with a new cast, new songs, new period-setting, and a new story. Would it hit or misfire?

The 2011 season had been set in the present day, with the workers opposed by a Polynesian boss and his daughter. There was a sub-plot involving the show’s heroine, Losa, and a fellow factory worker, but it was the community of workers that dominated the narrative. Dramaturg Jonathan Alver, former NZ Opera Director and West End Producer, came on board and encouraged big changes. The 2013 season was set in the 1970s during the first wave of Pacific migration to New Zealand. There was new racial and cultural tension by making the boss a Palagi, and turning his daughter into a son, Edward, meant a new romantic plot between Edward and Losa was what now dominated the drama. Favourites from the musical score remained, others were dropped, and five new songs were added with a new disco vibe. Critics raced to compare it to musical theatre greats: NZ Herald called it: the “Pacific Les Mis”. I described it as “West Side Story meets Saturday Night Fever with a Pasifika flavour”. It sold out and played to a mostly white middle class audience, many of whom had lived through that period. The show was slick, funky, and entertaining.

But something was missing. The focus on a conventional cookie-cutter love narrative, which we’d seen in so many musicals before, took away from the lives of the workers at the edges of the story. Composer and musician Poulima Salima acknowledges this criticism of the Arts Festival season. Well-known artists he spoke to had said that “the heart was sort of missing last year, a bit of a soul was sort of missing.” Vela Manusaute, who originally conceived The Factory, calls the 2014 show a “better version” that marries the best of the original 2010 workshop, the Mangere season, and the Arts Festival season. “It’s much more powerful, and the singing, it just gets better every time.” Poulima, whose focus this year is making sure that the cast are vocally tight, says “we’ve tweaked the lyrics, we’ve tweaked the script, we’ve tweaked the score.” They’ve bought back a few songs from 2011, and last week’s South Auckland season was one more chance to get it right before they meet the world.

Kila Kokonut Krew, whose motto is “From the Pacific we Rise” was founded in a “garage in Manuwera” by Vela, Anapela Polataivo, Stacey Leilua, Aleni Tufuga and Glen Jackson, all of whom are involved in The Factory project. If the company’s initials seem provocative, it is no accident; KKK was founded in frustration and anger. Vela had auditioned four times before finally being accepted into Toi Whakaari, the NZ Drama School. But after graduating he found there were few opportunities for a Polynesian actor. The indignation in his voice is apparent, as he explains how he felt: “You’re telling me I’ve paid my fees in the National School of Drama and now I’m on my own? If I knew that I’d be a lawyer, I’d have changed to something else, instead of this creative dream.” Vela says that for years he auditioned for Director Raymond Hawthorne without success. “Raymond came to The Factory, and I acknowledged him for not hiring me in any production.” Vela and the team recognised they had to make their own opportunity and tell their own stories. “Now we’re knocking on the international door.” Could The Factory be the first musical to come out of New Zealand to be a success on the international stage?

FATHERS AND MOTHERS

The Factory came out of a conversation between Vela and his mother, who said he should do a play about his deceased Dad; “My mum said do something serious, do something.” Growing up, all Vela remembered of his Dad was someone “working at the factory, drinking, getting into trouble, and when he died, he died.” Vela’s Father arrived in New Zealand from Niue in the 1970s, when New Zealand opened its gate to Pacific people. “I’m a product of them doing that at that time,” says Vela, “parents, aunties, uncles, left the plantations in a hurry to search for the milk and dreams, the promise.” It’s only now that Vela says he truly understands his parents, and their sacrifice. “My Dad’s passed away, my Mum’s older, my uncle’s older, and I ask myself, what happened to those people who came?” Vela’s father worked the factory floor at a bed factory. Vela says it was “hard” and that he’d sleep on the floor. Vela himself worked in a factory when he was 14 for a year. He thought at the time, “they’d better be a better life out there somewhere.”

Aleni Tufuga has played Kavana, Losa’s father from the beginning, and Kavana is the show’s rock, deeply committed to his family and hopeful for a better way. The opposing father is Richard Wilkinson, now played by Paul Glover, a difficult role that’s most prone to caricature, who takes a Bumble-like attitude whenever his workers ask for more. It is absent mothers that haunt The Factory’s narrative. While good-hearted Fa’afafine Misilei (Paul Fagamalo) takes Losa (Milly Grant) under her wing, Losa feels the heavy loss of her mother, killed in a cyclone back home. It is a loss that Edward (Ryan Bennett) bears too, missing his deceaced mother and watching his father retreat further into himself and against his workers; Edward is pulled between following his father’s wishes, and the spirit of his mother. There’s another absent mother too: the loss of the mother-tongue and culture. Mr Wilkinson thrusts English names on his workers, and in Money and English the chorus form an expressionist marching machine as they are drilled by Mr Wilkinson in these two priorities of his Factory. Samoana, Losa’s tribute to the islands, is a moving show-stopper; Milly Grant starts soft to evoke the land she left behind, the cast entering in traditional dress, before unleashing her full passion in a vocal powerhouse that sends chills up the spine.

THE SERMON

Vela sees The Factory as a celebration of his people who worked at factories, but in doing so it’s a deeply political work: “For an hour and ten minutes you’re going to hear a sermon of the Factory, a political statement of what the Factory represents.” The Factory is a first as a musical theatre work, but it’s also something of a first in terms of its politics. KKK have produced both drama and comedy in their history, from their debut play Taro King to their 2006 Comedy Festival outing Once Were Samoans, but generally Vela describes Pacific Theatre as light-hearted, too shy for politics or emotions. “That’s the way we are, that’s the nature of Pacific Islanders. We don’t want to piss people off.” Vela’s ready to piss people off, because Pacific people are not being recognised in terms of their contribution to the economy. “We’re always being put on the media as a bad people.”

“We don’t have a Treaty of Waitangi. Pacific people work hard, and should be recognised for it. We are plantation; we are the workers at the factory. I’m hoping my kids will find what we came here to look for, and I know they will…. They said it was a quiet country till we came along. We’re more educated now, more spoken about in society. We’ve got something to say to the world.”

‘What Do We Have’ is the show’s West Side Story America moment, as the chorus take stock of what they’d been promised, and what they’d been given (“You don’t have this, we don’t have this”). Mose (Taofia Pelesasa), the union rep involved in the Polynesian Panther movement, leads a hard-hitting sermon to the workers in How Come, angry at their treatment by society at large. Moses rages that they have “cut my mothertongue” and forced them to “speak the language of colonisation.” It’s a powerful moment that encourages reflection on where Pacific peoples sit within New Zealand now.

“A lot of people didn’t agree with us at the beginning,” says Vela, “but there was nothing out there for us. We’re a crazy bunch of people.” He says if they were to take the show’s message out to the streets protesting, they’d get arrested and taken to the “mad hospital”. “The safest place to do it is the theatre. The theatre accepts my madness, my ways of looking at how society is…. we could have given up a long time ago. We forever stuck at it. Burning all our bridges and saying there’s no going back.”

“I’m driving it to recognise our contribution; no-one cares about our contribution. But now that my father passed away, I do. I’ve got to recognise it. It’s a personal journey for me, and that’s why I’m so in it, heart and soul.”

WORKING AT THE FACTORY

It was a cold day when I visited The Factory rehearsals in Onehunga. Though the heater was blasting, the cast were wrapped in jumpers and scarves as they went through their movements and vocals for the finale; Paul Fagamalo had wrapped a garment over his ears to make Princess Leia buns. The singing, however, was hot, the melodies blending in all the right ways. They’re focussed on the details: where are they putting their hands, and there’s much discussion as to when is the best beat to take a breath to get them through the final song. To get this production on, everyone is working for below-commercial rates. “It’s like working the factory” says Vela. “We all share lunch. It’s a huge cast. It’s a lot of work. It reminds me of when my parents came to New Zealand, they were young Pacific Islanders, working the factory. Wow. I’m making a creative factory and I’ve kind of found that dream for me.”

The tour has been set up following KKK’s pitch at APAM (Australian Performing Arts Market). With assistance from Creative New Zealand and funding from Australia, they’re performing in Australia for two months at the Adelaide Cabaret Festival, Paramatta, Canberra, Wollongong, and the Gold Coast. Then it’s back to New Zealand for one week’s rest, then onwards to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe to play at Assembly Hall for an entire month – one of the larger venues at the Fringe and a huge coup. Vela dreamt about taking a show to the world when he was at Toi Whakaari, and as a young actor playing the extra, “carrying the spear for Michael Hurst and Paul Gittins.” Vela’s been there in spirit, but in International Producer William McKegg the company have someone “who’s been there before and worked there before” and “knows that world.” Vela admits that musical theatre is not his forte. “I can’t sing to save myself. But to tell the story at its highest form it had to be a musical theatre.”

Having the opportunity to go to Australia is important for the company, who want to ask the Pacific Islanders there, “why did you run away to Australia? For us people, what is the dream? For myself, I keep asking, every time I go back home to the islands, I think: man, so many empty houses, empty villages, we left our paradise for the coldness and the state houses, and the hardship of New Zealand. So who told us to come here? Someone opened that door, said New Zealand was a great place to be; bread, jam, peanut butter, all those. My dad came here first, then my uncle and everybody else. Man we came here, and it had a cost. It was hard for us to climb.”

THE WAY HOME

This year’s South Auckland season it was important to the company to get their blessings before they go overseas, and to acknowledge their forebears. As Vela explains, “we’ve got to have it in South Auckland to get the blessing of the village. Back at home you ask the elders for the blessing and when they give that we are able to move free, and you have the licence. It has to be – from the Pacific we will rise. And we’re going to celebrate New Zealand. The dream that was founded in the garage of South Auckland, now it’s built and made for the international audience. It’s a hit already. It’s like the All Blacks, they’ve already won before they step on the field. I keep saying don’t tell me it’s going to be a success, I already know.”

And for their South Auckland season, KKK have nailed it. What big budget musicals achieve with the help of hydraulics and impressive set changes, The Factory cast achieve with just one scaffolded factory floor set. The score holds up against the best. The cast are polished, high-energy, and bursting with infectious passion; they know why this is important and want us to know too. The world of commercial musical theatre can be an especially cut-throat and ruthless game, where large sums of money can be lost and won, but as someone who seeks out as much musical theatre as I can when I’ve been to Broadway and the West End, I’m confident that it can compete at this level. With one caveat – a tragedy in the third act has always been a difficult one to stage. On closing night of the recent South Auckland season, the audience were roaring with laughter. How will this moment play to an international audience?

We gave The Factory production a heart-felt standing ovation on closing, and in the foyer the actors were in hot demand as the audience lined up to take pictures. Vela was armed with his camera, soaking up the atmosphere and documenting that night’s milestone.

The Factory cast are now in Australia the first stop in a much bigger journey. Vela emphatically sees the trajectory of The Factory being “from Auckland to Broadway, there are no two ways about it. The West End. What the piece has to say is powerful and strong… It’s a personal achievement for myself; the guy who was the extra is going to start leading, without being boastful about it, that guy’s going to run the game...we’ve sparked the fire, now everyone is going to burn.”

“The Factory equals victory. I’m not going there to participate, I’m going there to win. I’ve been an extra for a long time, I’ve got to play the lead somehow mate.”