The Tiger Cub

A personal essay from Rose Lu’s debut book, All Who Live on Islands

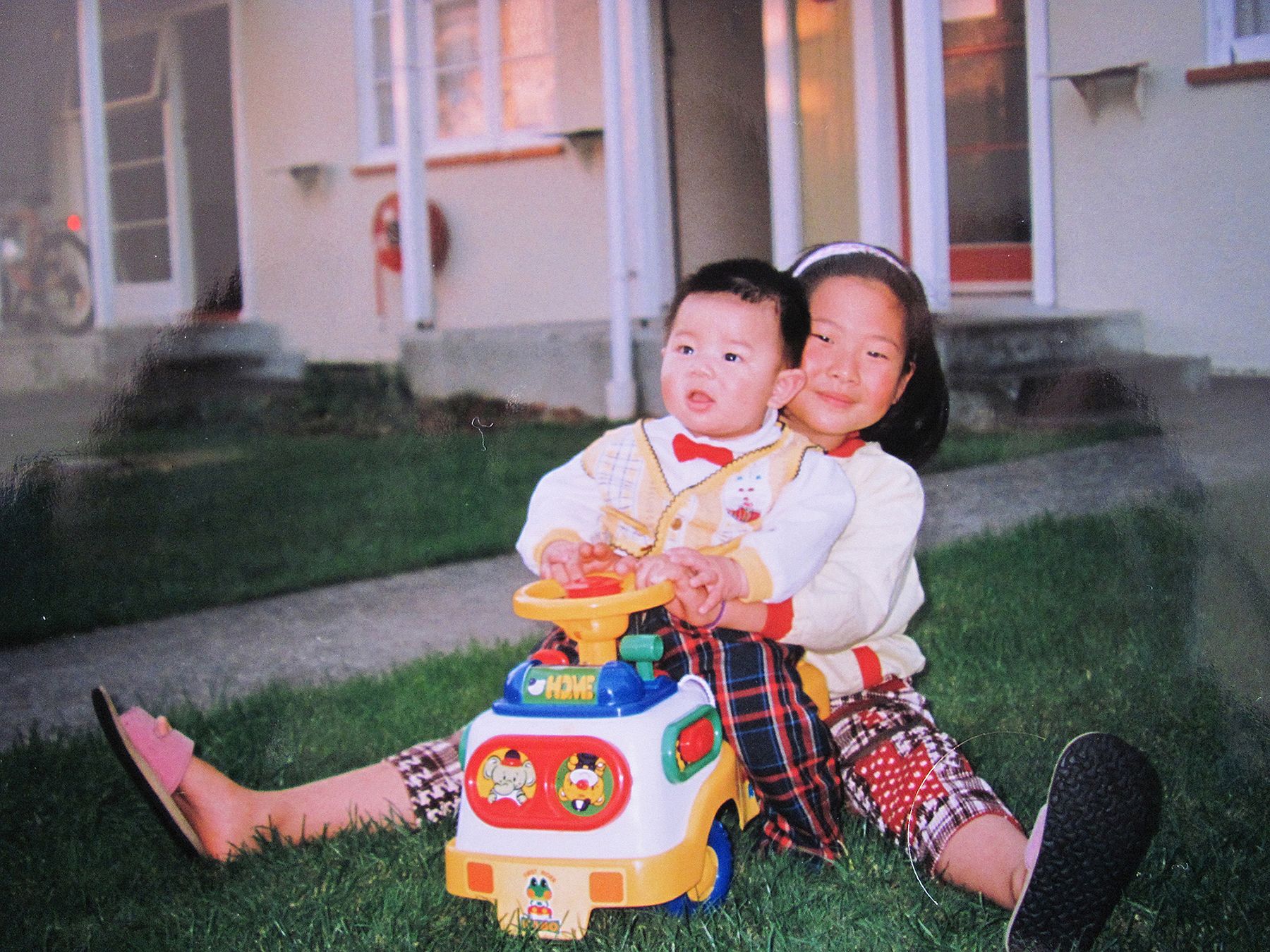

Rose Lu always wanted a sibling. Nine years and four months after she was born, a baby brother arrived. A personal essay from Rose Lu’s debut book, All Who Live on Islands.

You were born on a Sunday. I woke up in the bedroom I shared with Mum and Dad, and found that they were gone. This wasn’t unusual; I was accustomed to being left alone occasionally while they negotiated work and study.

I got myself out of bed and went to the fridge. For breakfast I chose the carton of sugared doughnut holes from the Pak’n Save bakery. The living room was dim but my parents said to keep the curtains closed if I was home by myself. I settled in front of the TV. What Now was on. That’s how I remember that the day you were born was a Sunday.

When you came home you needed to sleep in the room with Mum and Dad, so I moved into the study. Both my wishes, for a sibling and my own room, had come true at once. All the other kids at school had siblings; how nice it would be to have someone to play Chinese chequers with.

But the reality of having a baby around was that my parents had even less time for me. I contained my resentment for the first few weeks, but one morning before school I snapped.

Since the baby, Mum and Dad had been too busy to make me a hot breakfast even once. I burst into tears, wailing that they didn’t love me anymore.

The load eased when our grandparents arrived in New Zealand, and this little hiccup was forgotten. As soon as the month of con nement for mother and child ended, I pleaded to take you into school for Show and Tell. I was so proud to have a new little brother.

Nine years and four months is the gap between us. You were born in 1999, the Year of the Rabbit. Dad is also a rabbit. Mum and I are horses. In personality, though, I take after Dad: animated, gregarious, in constant motion. And you’re more like Mum: quiet, acquiescent, a content homebody. In pictures of Mum in her youth, when she had short hair, she looks exactly as you do now.

Our differences started out young. You were easy to raise. Obedient, staying exactly where you were left. Whereas at kindergarten in China, I scratched up a kid so badly they were taken to the hospital.

The only real discipline you received was a trick that Mum used to play when you were a toddler reluctant to go to bed. She would tell you that a family of tigers shared our house. They were a family like ours, with a mum, a dad and two cubs. As evening fell, they left the forests where they hunted during the day and headed to our lounge to make their beds for the night. In the morning, Mum would get up early and chase them back outside. Such was our agreement with the tiger family. I was a natural co-conspirator. Sometimes you would hear this story, pout, and ask, “为什么姐姐不去睡觉?” | “Why does older sister not have to sleep?”

“姐姐大了,老虎怕她了。” | “Older sister is big now, the tigers are afraid of her.”

I exchanged a glance with Mum. “这一家老虎很凶呀! 牙齿

很尖!” | “Thee tiger family is very fierce! They have such pointy teeth!” I would say to you, eyes wide and arms raised for effect. Your mouth set with fear. You would let Mum pick you up and carry you out of the lounge, leaving me in the company of tigers.

My semi-parental relationship with you continued when I moved to Christchurch for university. I convinced Mum and Dad to send you down to visit me in the overlap of our holidays. For a week I cooked dinner for us and drove you around the city.

One of my flatmates had gone away for the break and let you have his bed. In the mornings I went to wake you up and was taken aback by the length of your body. When did you get so tall? In my mind you were still my little brother, with a small body I could lift and carry. But at ten years old you were about to surpass me in height.

As soon as you became tall, you started to make yourself smaller. “Matthew 站直!” Mum would bark, pressing your shoulders back with her paws. For a moment you would raise your head and bring your neck back in line with your spine. It was a small improvement to your posture, but your shoulders were still up by your ears, maintaining the hollow at the centre of your chest.

I felt a sharp obligation to protect you from—or at least warn you about—the perils of growing up in Whanganui with our parents. Mum and Dad were inclined to say things like, “最好你们俩的性格换一下。你真不像女孩,一整天在外面疯玩 儿, Matthew 也不像男孩,赶也赶不出去。” | “It would be best if you two swapped personalities. You’re not at all like a girl, spending your days outside like a wild child. Matthew’s not at all like a boy—we can’t ever get him to leave the house.”

When Mum said that, I rolled my eyes and looked at you. Your face bore a wooden expression. From about fourteen you wore this face, with downcast eyes and hard lips and cheeks. I couldn’t tell if you were internalising their statements or simply ignoring them. You had never been talkative, but as a teenager you became taciturn in that stereotypical way.

All I hoped to do was reassure you that it was safe to speak to me, and trust that you would reach out if you needed to.

We went on long walks around the neighbourhood so we could talk freely. The conversation always felt hard. I didn’t want it to be so one-sided, me spouting opinions to counterbalance what you were hearing from Mum and Dad, but no matter how much silence I left, you would never fill it. Affirmatives were the most I ever got from you, when what I wanted was some reflection to show that you had understood.

Perhaps I was looking for too much. I couldn’t put myself back in the mindset of my teens to assess whether I would have been capable of such a conversation. I could never tell how the conversation was going for you. Your face was impassive, drained of any emotion. Did it feel patronising, in the way that any received wisdom does at that age? But you must have enjoyed our conversations enough to keep agreeing to go on walks. All I hoped to do was reassure you that it was safe to speak to me, and trust that you would reach out if you needed to.

If my friends asked about you, I would often say, “Picture someone who is the complete opposite of me.” It wasn’t just our personalities—our experiences were completely different. My childhood was one of upheaval. I attended five primary schools, one intermediate school and two high schools. Your schooling was all in Whanganui.

After intermediate, you were sent to a private school and started going to compulsory chapel every week. Every evening and weekend, you were busy with school activities. If it wasn’t some sort of sports practice, it was an extension maths or science class. The focus at my public school was simply to pass; your school demanded excellence.

Either implicitly or explicitly, I imagine that your school told its students that they were important and would achieve great things. Your peers had iPhones and went overseas in the holidays to spend time with their parents who worked in multinational companies. They strolled through the manicured grounds with innate self-assurance and high expectations for all aspects of their lives.

In Year Eleven you started rowing. Your arms and legs swelled like bean pods, skin pulled tight and shiny. You gained about fifteen kilos of muscle. It hung on you like a heavy cloak you were yet to feel comfortable in. The way you held yourself hadn’t changed. You still hunched, shoulders collapsed over your sternum, making yourself seem small even though you no longer were.

Mum and Dad never had time to hang about at your rowing practice, so they sent me along one Saturday morning. Gazebos were set up at the riverside. Under the constructed shade, white dads flipped patties and white mums brought out containers of baking. I was the only sibling there, and I didn’t know which category of white parent would be more interesting to talk to.

Boat after boat skimmed past on the Whanganui River. They came in ones and twos, young men pulling in unison. Sitting on the bank, I was too far away to be able to distinguish you from the rest of the pack. How natural did it feel, I wondered, to perform these long strokes? Dressed in the same black and blue, looking like one of the team.

I talked to a few of the rowing mums and idly sampled cupcakes. They tasted homogenous despite the colour range in their pleated cups. Our conversation died fairly quickly as I didn’t know their families or sons, and the types of questions they asked weren’t ones I wanted to elaborate on. I folded the waxed wrappers into quarters and then eighths as I looked at the dads behind the grill. It would be nice to have something productive to do with my hands.

At the end of practice the boats were hauled out of the river and stacked in the boat shed. You were silent amid the throng of young men coming up the bank. Their banter was a combination of boasting and teasing, the same coarse yells I remembered from high school. One-upping each other in the number of muscle-ups they could do. Girls’ names thrown around like paper into a wastebasket. The word “gay” used as a pejorative. Ten years had passed since I was last in school, but the Lynx Africa masculinity was yet to be retired.

As soon as the tidying was done you grabbed your stuff, ready to leave. A chorus of byes came from your teammates, as well as a sharp laugh that I couldn’t interpret.

“You don’t want to stay and eat some sausages with your friends?” I asked.

You gave me a look. We both knew that lunch would be much better at home.

We wandered towards the parked car. “So, are you friends with those guys?” I asked.

“Not really.”

“I guess they’re quite different, huh?” “Yeah.”

Did you know Dad believes that auspicious events occur every seven years?

Did you know Dad believes that auspicious events occur every seven years? Well, give or take. Once he marked out the beats of his life to the cadence of seven: going to university in Shànghai, leaving China for New Zealand, buying the shop in Whanganui. There are a few missed beats in there; places where he was too young or too tied down to seize the opportunity waiting for him.

According to his rough calculations, 2018 was the next big year. I think he was right. It was a big year for the entire family. Our parents prepared to sell the shop. I went back to university to do my masters. You moved out of home and started your first year of university.

In my head I picture you walking the path I abandoned. You enrolled in a bachelor of health sciences at Otago University, and had a room at Carrington Hall. It was the same degree and hall of residence that I was accepted into ten years ago. Before you left home, you packed your things in the same purple and black suitcase I had used.

The Lù family had always been doctors, except for Dad and his brother, who didn’t do well enough in the 高考 | gāokao to go on to study medicine. Our dad was the smarter of the two, and from practice tests it looked likely that he would succeed. But on the day he got sick and underperformed, so that was that. At the time, it wasn’t possible to retake the 高考. Everyone was granted just one opportunity to improve their future through education. Like his older brother, he had to settle for being an engineer instead.

Of their children, I was the first to secede from studying medicine. I didn’t even start the undergrad degree. Simon, our only cousin, got much further. He completed a biochemical engineering degree in Canada as his pre-med requirement.

Next came the medical college admission test and interviews. He failed to get in. So he retook the MCAT and the interviews at the next opportunity.

In total, he failed to pass the day-long medical entry exam seven times. At this point, he was forced to stop because he had reached the lifetime restriction on number of attempts. If it were up to him, maybe he would still be taking that exam now.

Dad joked that you were the last member of the family left who could become a doctor. I didn’t know how seriously you took his words. I suspected that, like me at your age, you had no idea what the other options were. Back then, the only adults I interacted with were teachers, our parents, and my coworkers at the Mad Butcher; none of their jobs seemed like a good fit for me. I was a smart kid so traditional professions like medicine, law or engineering seemed like the way to go. They were jobs I understood only in the abstract, but no one around me could offer a useful description of what they were really like. It wasn’t until after I moved to Wellington that I understood the array of options I had at that time, but also the avenues that were never open to me.

I was excited to see you leave home. Life was going to change and improve in ways you couldn’t have understood at the time.

For years you expressed ambivalence towards the idea of enrolling in med school. But in Year Thirteen, you became fixed on the idea. I assumed the pressure came from Mum and Dad, but they said it wasn’t their influence. They had reassessed your suitability for medicine, and, given your introverted nature, concluded that your bedside manner would be inadequate. But you were firm in your choice, even though you couldn’t explain it to me when I asked.

“I dunno. I think it’s interesting,” you replied in your usual muted way. Two sentences were about all that you verbalised of your decision. Were you drawn in by the prestige of med school? Was it pressure from other kids who aspired to go there?

Did you feel a need to prove yourself? Your motive was a mystery to everyone. Regardless, I was excited to see you leave home. Life was going to change and improve in ways you couldn’t have understood at the time.

I wanted us to speak more often, but we weren’t in the habit of messaging, so it was hard to start up out of the blue. From a distance it looked like you were having a good time. I liked a picture of you going to the toga party with a group of friends who were all of Asian heritage.

Mum kept me updated on how you were. Her news revolved around assignment grades and exam results. Many of our parents’ friends had children enrolled in first-year health sciences. It felt like Mum and Dad were keeping closer tabs on your grades than you were.

My first year at university featured midweek absinthe shots and missing nine o’clock lectures. But during your rst year you were chained to your desk. Your first lecture was at eight in the morning and you’d study until eleven every night. Eleven was considered an early bedtime. Other students claimed to be up until two or three, studying hard and psyching out the competition with their unfaltering work ethic.

If you weren’t studying you were reading posts on the med school forum, a place for students to post their grades and share their experiences. At the end of the year, the moderators of the forum would reverse-engineer the exact grade average needed to gain entrance to med school. Acceptance had such a narrow rate of success, and every year thousands of capable young people were crushed by these impossible standards.

On the page you spoke with no ums or ahs, no hesitation, no maybes. Your voice was suddenly clear and eloquent.

We would go months without talking, but I was never worried. I had assumed that a lack of communication meant that you were fine. Late one evening on the cusp of spring, you sent me a four-page document through Messenger. I had never known you to write. On the page you spoke with no ums or ahs, no hesitation, no maybes. Your voice was suddenly clear and eloquent. “I’ve never really been able to say everything I’ve wanted to when I talk to someone about my mental health,” you wrote.

“I always end up chickening out just before I say it. I can chalk that up to how awkward I am. The amount of time I’ve wasted just dwelling on what I’m going to say is ridiculous, especially considering I don’t even end up saying half of what I intend to . . ."

"Trying to piece together exactly how I’ve been feeling over these past months is difficult. What I’m trying to get at is that I’m not sad. At least that’s not the whole story. Depression is a lot of different feelings. None of them are good. It’s an exhaustion that keeps me in my bed all day. There’s no drive, no motivation to go out and live my life. It’s a haze that blocks out everything good in the world and leaves me alone with my self hating thoughts. Let’s steal an analogy. ‘Physically it feels like I have the flu. Mentally it feels like I deserve the flu.’ . . ."

"This way of thinking has been burnt into my head."

"I was depressed in high school. Probably. Might have been teen angst that I’m overblowing but whatever. I think a lot of the reason I’ve found it so difficult to talk about is how unaccepting we are of mental illness. The label of depression carries so much weight. That’s in the past now though. I’ve got friends that are willing to support me through this. It’s not like everything is fixed now though. I’m still so terrified of talking about this. This way of thinking has been burnt into my head. It’s why I waited so long to tell you. Part of me is still plagued with so much doubt and paranoia that I freeze up every time I talk about my mental health . . ."

"Recovery has been tough. I think it’s because of how much of it is on me. I described it to my therapist as being as if we treated broken legs by having the patient run a marathon. She found it pretty funny. I’m trying my best and that’s all I can really ask for at this point. I guess I viewed therapy as this cure – all that would magically take all my problems away. All change pretty much has to come from me.”

My initial reaction was a feeling that I had failed you. Were there signs I should have seen earlier? Being quiet wasn’t necessarily an indication of troubles, and neither was a lack of strong camaraderie at high school. We weren’t people who suited Whanganui, but I had forgotten how bleak that felt at the time.

I assessed the severity of the situation through the counselling basics I had learned at Youthline. Were you at risk to yourself? No. Had you sought professional help? Yes, you had gone to the doctor and been prescribed antidepressants and referred to a counsellor. Did you have good support networks? It sounded like you had good friends, despite your self-effacing words about being awkward. I resolved to call you every week.

“Do you think you understand your feelings?” “Yeah.”

“Okay, what things make you happy, or sad?”

A long pause.

“I dunno.”

“Well, do you think that conflicts with what you just said?

About understanding your feelings?” “Maybe.”

Our phone calls were like pulling teeth. I hoped you were chattier to your counsellor. I broached the idea of you telling Mum and Dad how you were feeling. Mental health wasn’t something that they had a good grasp on, but I thought it would be different if it was their own kid. They would need to get better at talking about it.

Understandably, you were hesitant about the idea. “Maybe,” you replied.

I thought about the last time I tried to raise the topic of mental health with Mum. She had been recounting a newspaper article to me, about a successful and beloved doctor in Whanganui who had died by suicide. He was active in his community, cheerful and kind.

“我不理解。” | “I really can’t understand,” Mum said, shaking her head.

I got that heat in my chest, the one that accompanies the expression of something important but difficult. In English I could have said something articulate, but all I managed to spit out was “这些东西表面看不出的。” | “You can’t spot these things.”

She looked at me, giving a half chuckle. “你不是说你有过 depression吗?” | “You’re not saying you had depression, are you?”

“不是。” | “No.” But I wanted to say that I had been close to people who did. I saw how it sat on them, how they had to keep dragging it around. How you might need to learn how to manage it for the rest of your life, rather than ever putting it behind you for good.

“Matthew 这学期一直在生病。” | “Matthew’s been sick this entire semester,” Mum announced as soon as I got into the car. We were heading to the airport to pick you up. Your rst year at university was three quarters of the way through.

“他说晚上一直睡不着觉,每天上课很累。医生给他配了点儿 药,可是没有什么用。唉,我看他这个状态可能考不上医学院。” | “He can’t get to sleep. He’s tired in class every day. The doctor prescribed him some medicine, but it hasn’t had any effect. Ai, in this condition I don’t think he’ll be able to get into medical school.”

What an interesting half-truth you had told her. She spoke in a rush, tting as many details as she could in the fteen-minute drive to the airport. She seemed more concerned about the impact of the illness on your studies than about how we might help you to recuperate. Reading between the lines it was obvious what shape your illness had, but Mum appeared to have taken your words at face value. Like me, you had a hard time lying.

This was to be the first time I would see you in person since you’d written to me. I prepared myself for a lack of apparent change in you, but I was still unsettled by how routine your behaviour was. We went to yum cha and you ate heartily, having missed breakfast due to sleeping in.

“Matthew 你看上去长胖了。现在体重多少?” | “Matthew, you look like you’ve gotten fatter. How much do you weigh now?” Mum asked, pushing the plate of 扣肉 | steamed pork closer to you.

“I dunno,” you replied.

“是不是太用功学习了,没时间去跑步?” | “Is it because you’re studying too hard, you don’t have time to go running?”

You gave a half-nod, half-shrug. I changed the topic. You had a full week ahead of questions like these. After lunch you and Mum were heading back to Whanganui while I remained in Wellington. It wouldn’t be until Christmas that all of us were together.

In those intervening months, you spent the days sleeping in and not leaving the house. Socialising had never been a priority of yours, but these holidays you were more withdrawn than usual. Part of it was exhaustion; you needed to recover from the stress of the year.

I worried about your situation. Your school friends were back for the holidays, but you didn’t even send them a message. One of the friends you were planning to flat with the following year lived in Wellington, so I offered you the fold-out couch at my place, but you never organised a bus ticket to come down. The most I could wheedle out of you was an agreement to come tramping with me and my friends over the New Year. From a young age you had preferred the company of people older than you.

Exam results were released a few weeks before Christmas, with letters of admission to follow. It wasn’t looking good. Your grade average from papers alone sat in the nineties but it wasn’t enough to make up for your middling score in the UMAT, a three-part test on logic, empathy and non-verbal reasoning that was notorious for being difficult to prepare for.

I could measure Mum’s worry by the number of WeChat voice messages she left me.

Each year, the cut-off became higher and higher. There was speculation that there were even fewer places available this year, because the programme was accidentally oversubscribed last year. It was not a lucky year for your cohort of students.

Three days before Christmas, it was confirmed: you had not gained a place in medicine, and you hadn’t even made the waitlist. I could measure Mum’s worry by the number of WeChat voice messages she left me. She described you moping around the house, your face a downturned mask. Everyone in the house stepped carefully around you, afraid of doing anything to upset you any further.

Given your results, Mum thought the best course of action was to start over with a new degree—perhaps engineering at Canterbury. You weren’t interested, though. You wanted to finish your bachelor of health sciences and reapply for medicine. You wanted a second chance.

*

At Christmas, everything seemed normal at home except for the boxes dotted around the place. Our parents and grandparents were preparing for the big move. From 2019, the Year of the Pig, they would live in Auckland. You glanced up from your phone and said “Hey” as I came into the lounge carrying Tom’s and my luggage.

Dinner that night was a little off. Dad was his usual self, yanking open the top cupboard to get the 白酒 | báijiǔ, but Mum responded by rolling her eyes. Thankfully no one broached the subject of your future.

The next morning, Mum cornered me in the kitchen. The shop was quiet and you hadn’t woken up yet. “你知道爸爸昨天 跟 Matthew 说什么吗?” | “Do you know what your dad said to Matthew yesterday?” she said. “男子汉要持之以恒。” | “Men need to persevere.”

I didn’t know Dad still held out hope for a doctor in the family.

Mum continued, “今年你看他的身体弄成这样。这么大的压 力他受不了了。让他再这样子两年,他肯定坚持不下来。” | “Look how bad his health has gotten this year. He can’t cope with this much pressure. Two more years like this, he definitely won’t cope.”

You found it patronising when your counsellor partly attributed your depression to university, but there was some truth to it. In the second half of the university year you went to the dining hall for dinner, alone, just before it closed. That way you didn’t have to waste precious studying time chit-chatting with your friends, and you could have a double serving of dinner as there were no further students to feed.

Mum was furious when she heard about this behaviour. Better exam results weren’t worth this self-enforced isolation.

She was trying to make me her accomplice again, but this time you weren’t a toddler.

“你们徒步的时候一定要跟 Matthew 好好的聊一聊,他不能 继续读这个专业了。” | “When you’re tramping you must have a proper chat to Matthew. He can’t keep studying this degree.”

She didn’t have confidence in your ability to make your own decisions and to come to terms with failure. I agreed to talk to you, but not to convince you of anything. Shrugging, I reminded her how ineffective her attempts to discipline me were. Unlike when I was a teenager, I could see that her concerns came from a place of care, but instead of working with you to understand what you were going through, she had skipped forward to what she thought was a solution.

At the root of her worry was your health. It felt like we were circling around the topic of depression, getting closer to establishing a common vocabulary to talk about it but not quite landing in the same place. In the past, her understanding of the concept of mental health had been simplistic. She could sympathise when somebody had an emotional response to significant trauma, but she couldn’t understand a condition that was an underlying, simmering discomfort, or something that came and went, needing constant attention and management. This time it felt different.

“你知道医生给 Matthew 开了什么药吗?” | “Do you know what type of medicine Matthew was given by the doctor?” I ventured.

“不知道具体是哪一种,但是他说是可以帮助睡眠的。” | “Not the specifics, but he said they helped him sleep.”

“他不让我告诉你,可是药是 antidepressants.” | “He told me not to tell you, but they were antidepressants.”

She paused, lips parting and closing again. “我问了赵叔叔。” | “I asked Steven about this,” she said, speaking of our family friends, the Zhàos, who were doctors in China. “我担心弟弟变 胖了,就想知道哪些药会引起发胖。我跟赵叔叔描述了弟弟的状 况,他说听起来像是 antidepressants.” | “I was worried because Matthew was getting fat. What sort of pills can make you fat? I described his symptoms. Steven said that it sounded like antidepressants.”

We have eaten so much bitterness in our lives just so that you and your brother could have more comfortable days.

Then she said, “我们一辈子已经吃了这么多苦,就想要你跟 弟 弟 的 日 子 过 得 舒 服 一 点 。你 劝 他 转 个 专 业 ,没 必 要 走 这 条 路 。” | “We have eaten so much bitterness in our lives just so that you and your brother could have more comfortable days. You have to persuade him to change his degree, he can’t keep walking down this path.”

*

Our tramping route circled Mt Ruapehu, passing through beech forest, lahar zones, desert terrain and brisk springs. All going to plan it would take six days to walk the track. The four of us—me, you, Tom and Kezia—drove in two cars.

In the first half of the drive you rode with Kezia. If it had been a different friend I would have worried about the potential for it to be awkward, but Kezia had a knack for making people feel comfortable. In Tūrangi we stopped to carb-load on pies and chips, and swapped passengers. The next leg was you and me, cocooned in the front seats.

Our lives had diverged at such a young age, and from what I could glean about your first year of university we had continued in these opposing directions. The moments that held signi cance for you, the ones that built into a series of quiet acknowledgements about the world, were yours alone to untangle. I waited to hear what you had made of it so far.

“I’m going to finish health sci, and think about whether I want to re-apply for med.”

“Yeah, you’ve said before that some people prefer completing the bachelor’s so they have more time to think about doing med?”

“Yeah. And second and third year aren’t as hard as Mum and Dad think. I’ve talked to a bunch of second and third years and they all said first year was the hardest.”

“That makes sense. What do you think you’d do if you don’t get into med again?”

“There’s a postgrad degree in biomedical engineering at Auckland Uni that looks interesting, I’d probably do that.”

I chuckled to myself. It looked possible that our family was moving away from medicine permanently.

“There’s the masters in creative writing I did last year as well, in Wellington. I think that’s something you could do.”

“Hmm. Yeah, maybe.”

The conversation stilled for a bit. We turned a corner and Mt Tongariro came into view.

“Hey, did you end up going to the doctor in Whanganui? Surely you would have run out of antidepressants?”

“I stopped taking them before I left Dunedin. They weren’t really doing anything, so my doctor told me to stop because of the side e ects.”

“Oh, okay. How are you feeling?”

“Fine.”

“Do you feel better than you did in the middle of the year?”

“Yeah.”

“You seem happier.”

“Mmm.”

On the tramp, you were happy to take your share of the group food but you wouldn’t think to do the cooking or cleaning up. At first the rest of us took care of it—there wasn’t a lot to do, and it was quicker to just do it. On the third day, I told Tom and Kezia that we shouldn’t shy away from giving you specific cooking and cleaning jobs. I washed the plates from dinner and gave them to you to dry. The motion of your two hands around the rim of the plate had a staccato pattern that gave away your inexperience.

“When you make the chore roster in your flat, make it a job for someone to go around and remind everyone else to do their chore for the week,” I said.

You nodded.

By the fifth day you automatically got up to help when someone started to collect the dishes. You were chatty when you got talking about something, usually to do with human biology, and you slid in the occasional zinger. Even though your year had been hard, I noticed that you smiled more. You would squeeze your eyelids at something particularly funny, and your eyes looked like tadpoles, tails shaking with delight. Your posture was better too; perhaps this was because you stopped rowing.

It felt like I was watching you flicker between two versions of yourself. As you continued to build confidence, your quiet nature became more contemplative, more self-assured. I couldn’t divine what was ahead of you, but I knew your future self would be capable of handling it.

After the tramp, we stopped in Hawke’s Bay to visit Sylvia, my yoga teacher, to lengthen our hamstrings back out again. She watched as you walked into the studio, and directed you to the mirror. You were wearing your black rowing shirt and shorts; the only exercise gear you own. Sylvia stood behind you. She took a strap and placed it around your upper arms, rolling them back and down so that your sternum, collarbone and chin would lift.

Your arms were pinned backwards and your shoulders drawn down. Sylvia pulled the strap tighter, winching your arms back even more as you looked directly ahead.

I looked at your reflection. Your shoulders were broad, much broader than I thought they were. Your expression was neutral, unafraid of the space that your frame occupied. And in your chest centre was your heart, open and ready.

Rose Lu’s book All Who Live on Islands is published on 14 November 2019 by Victoria University Press.

All photographs courtesy of Rose Lu.