The Past Needs New Authors

Reuben Friend's thoughts on Brett Graham’s 'Tai Moana Tai Tangata' at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre.

Kārearea soar overhead as I write this, preying on rabbits in the paddock on the other side of the Waiwhakaiho River, where my wife’s family owns a small block of farmland in New Plymouth. On the hill overlooking the property is an urupā, a single person buried in a tiny plot squeezed between two townhouses on the new subdivision. A Māori chap named Kingi was laid to rest there in 1917. As we sip our morning coffee, talking about rising property values, I think about Kingi and the view he once had over the property we occupy today, knowing that land in Taranaki has always come at a high price.

We’ve come down to see the family, and to visit Dr Brett Graham’s momentous new exhibition Tai Moana Tai Tangata at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre. Brett Graham’s interview with Curator Contemporary Art and Collections Hanahiva Rose about Waikato connections to Taranaki has me eager to learn more. I’m not from here, but like Graham my Tainui whakapapa is a complex web of networks that links me to this place.

It’s sunny and we’re in good spirits as we drive to the gallery on New Year’s Eve morning, passing Hēnui Walkway on the way. I chuckle to myself about the name ‘big-mistake’ (literal translation) before realising that this is the ‘Hin-new-wee’ Walkway that a lovely Pākehā kaumatua had recommended I visit earlier this week. I’m still thinking about the word ‘Hēnui’ as we walk into the gallery, wondering if other people enjoy the irony of mistakenly pronouncing the word ‘mistake’. I’m delighted when the first label rewards me with the origin story behind Hēnui or, more correctly, Taiporohēnui.

Cease Tide of Wrong Doing, Taiporohēnui is the first work in the exhibition, a gigantic two-storey niu pole that rises from the ground floor and stretches skyward into the gallery spaces above. It’s painted satin black and is entirely adorned with Graham’s signature pākati surface carving. The impressive feat of creating this ‘tower of power’ was accomplished with the help of carver Matene Sisnett, with father and daughter team Eugene and Maioha Kara assisting on other works in the exhibition.

This was the first time that I’ve felt the energy of a ritual activation

Followers of the Pai Mārire faith erected niu poles to receive and transmit messages through the air, like transmission towers, with hau (wind) being one of the principle media of communication between God and the prophet Te Ua Haumēne, who founded the movement in 1862. The label for the sculpture credits the title Cease Tide of Wrong Doing, Taiporohēnui to a quote from Te Whiti o Rongomai in 1879, referring to the illegal confiscation of Māori lands and the corrupt structures of government that hold money aloft as the ultimate source of power. The label goes on to state that the concept of taiporohēnuiwas instrumental as the guiding principle underpinning the 2015 Taranaki Iwi Treaty of Waitangi Settlement Claims.

It is a monumental artwork; in form, scale and the execution of whakairo, but also in terms of its emotional and thematic gravitas. A few weeks earlier I had attended the exhibition’s opening, when the gallery was filled with people and the reverberation of Pai Mārire incantation. Although there are numerous niu poles in the Waikato and Whanganui, this was the first time that I’ve felt the energy of a ritual activation, with the congregation encircling the niu, chanting in unison, collectively sending messages of hope, peace and restitution into the air.

After the blessing, the gallery team put on morning tea and members of Brett’s delegation held wānanga around the niu, with the artist and knowledge holders sharing stories, whakapapa and histories of conflict and connection between Taranaki and Tainui. Wearing a fitted, dark blue and purple pinstripe suit, Brett looked like a modern-day prophet with his arms outstretched, channelling energy from the niu as he preached his gospel. We learned that Waikato and Maniapoto forces invaded Taranaki exactly 200 years ago and continued to do so in the decades leading up to the New Zealand Land Wars. It was during this time that Te Ua Haumēne was captured by Waikato forces. He was just a child in 1826 when he was taken from here to be raised as a slave in Kāwhia.

Baptised by war and later by the Wesleyan Church, Te Ua Haumēne returned to Taranaki in the 1840s as a man of faith and of action, supporting the Māori King movement against the government after the Taranaki wars broke out. He structured the Pai Mārire faith with two key roles under his command, the Tuku Pai (Duke of Peace) and Tuku Akihana (Duke of Action), with respective duties derived from the biblical Book of Revelations to promote peace and to respond to Pākehā aggression through necessary means, including taking up arms to liberate the oppressed and strike down the unjust.

Dr Brett Graham speaking in front of Cease Tide of Wrong Doing, Taiporohēnui, during the opening day wānanga for Tai Moana Tai Tangata.

Themes in the exhibition are heavy, but Graham and curator Anna-Marie White unpack these complex narratives with clear, concise and even-handed messaging. Tainui iwi caused huge devastation here in Taranaki, decades before the British fired their first shots at Waitara in 1860, and neither artist nor curator downplay or shy away from these facts. In fact, they are central to the narrative.

It is heartening to see the gallery has steeled itself to address these histories, knowing that some visitors may find these narratives difficult to confront. Māori representation isn’t something that New Plymouth is particularly well known for, and my thoughts turn to ex-Mayor Andrew Judd and the abuse he received from New Plymouth locals for not “sorting out the Māori problem” here. I worry the artist and gallery may similarly face backlash from visitors who might feel affronted about the way these stories are told in the exhibition, but looking around the gallery on my second visit I feel encouraged to see it humming with a diverse range of visitors who seem completely enthralled by the project.

I feel the universe fold in half, as Tāmaki and Taranaki press together for a moment

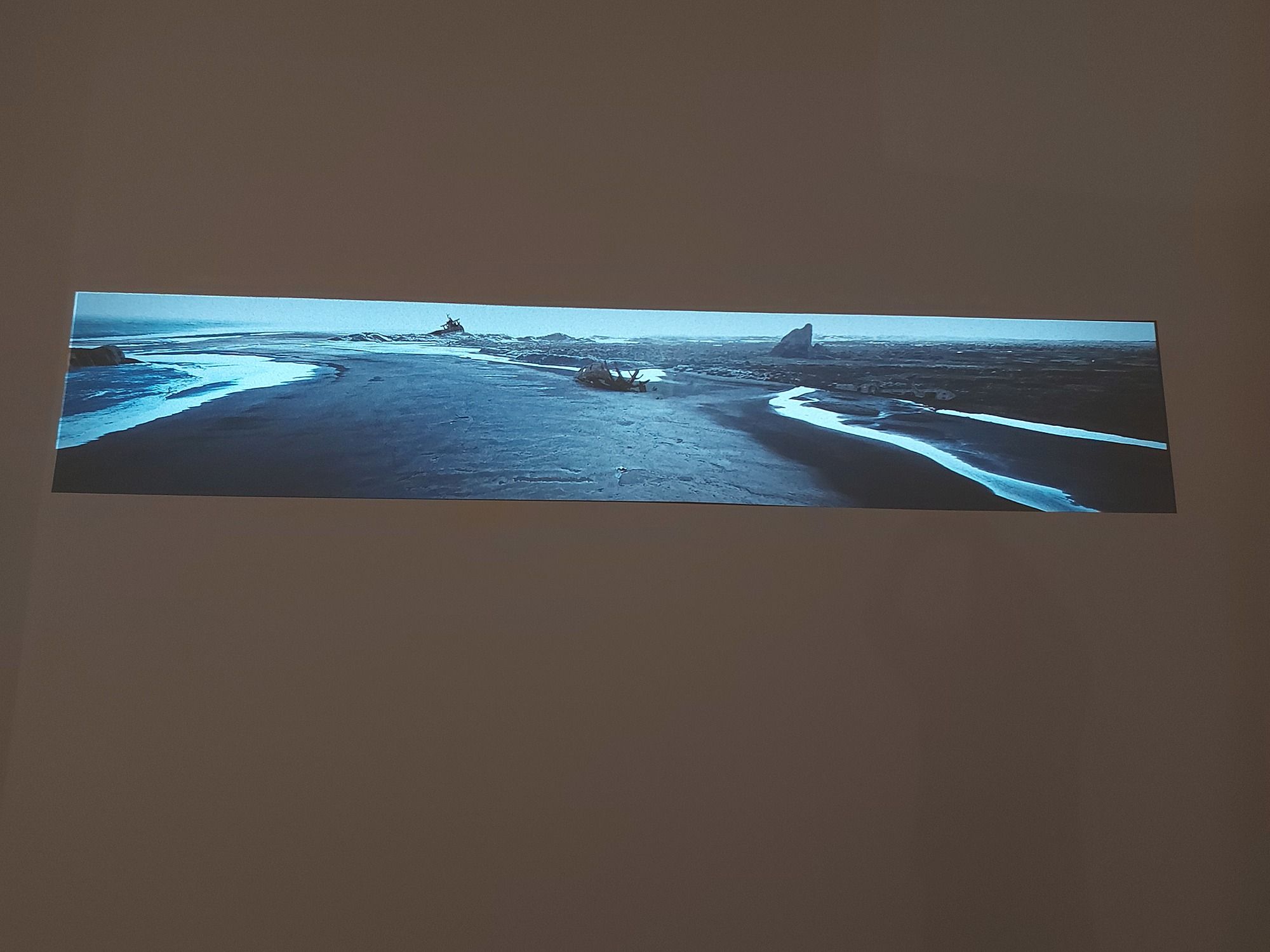

Each of the sculptures in the exhibition appears to be paired with a corresponding moving-image artwork. There is a hazy, jittery quality to some of the footage, giving the impression that at times we may be watching archival footage of a grim, inhospitable Taranaki coastline. The ominous tone is intentional, with the artist reflecting on archival records of the colonial settler experience of fear and trepidation in New Plymouth during the years of the aukati, the boundary line between Crown lands and Māori land in Taranaki and the Waikato. Trespass was punishable by death.

Cease Tide of Wrong Doing, Taiporohēnui is accompanied by Te Namu, a moving-image work showing a desolate southwest Taranaki coastline littered with oil drilling operations. We learn that this site is where the mail steamer Lord Worsley was wrecked in 1862, leaving its passengers stranded behind the aukati line, causing fear amongst settlers for their safety. This incidentforced Te Ua Haumēne to reconcile his contrasting Christian beliefs with his allegiance to the Māori King. This portion of the exhibition concludes with information about Pai Mārire beliefs and how they formed the foundations of the non-violent resistance movement among Tainui and Taranaki iwi residing at Parihaka. When government forces invaded the Waikato in 1863, the Māori King Matutaera came to Taranaki. There he was baptised into the Pai Mārire religion, changing his name to Tāwhiao (encircle the world) and forming an alliance known as Te Kīwai o te Kete that is still observed today.

Heading upstairs I have a surreal experience when I get a phone call from Zane, an old friend who has just paddled his waka ama from Mangere Bridge to Āwhitu, near the Manukau Heads in Auckland. I tell him that I’m literally standing in front of Grande Folly Egmont, an artist’s sculptural recreation of an old lighthouse that was installed at Āwhitu in 1874.I read him the label that talks about Taramainuku, one of the two taniwha who reside in the Manukau Harbour. “Out of it,” he reckons, telling me that he just saw Taramainuku on his way out, in a stretch of water that is notoriously turbulent with alternating channels of incoming and outgoing water. Usually my childhood home in Māngere feels a world away from rural New Plymouth, both culturally and geographically, but now I feel the universe fold in half, as Tāmaki and Taranaki press together for a moment. I’m starting to feel that maybe my connections here are more significant than I realise.

Installation view of Grande Folly Egmont with the moving-image work Manukau visible in the background.

Sculpturally, Grande Folly Egmont has not been indulged with the same intensity of surface design as other works in the show, and it feels a bit like a tall wallflower in an attention-grabbing competition. This simplicity of form is a welcome visual relief, with the solemn tomb-like feeling being purposeful aesthetically and thematically. Grande Folly Egmont is essentially a war memorial that also holds personal significance for the artist, whose ancestor Joseph Graham was claimed by Taramainuku when his boat capsized there in the Manukau Harbour in 1874. One of Joseph Graham’s children, Arawhena, was part of the Tekau-mā-Ruā, a group of Māori sent by King Tāwhiao to reside at Parihaka to reinforce spiritual and political relations between whānau and iwi here in Taranaki.

Āwhitu was a strategic military location during the New Zealand Land Wars. Tainui iwi who dwelled there were bombarded by cannon fire from British ships in preparation for the invasion of the Waikato and Taranaki. In a related moving-image work, Manukau, we see dramatic drone footage of this location, looking like it was somehow captured in the decades after 1863 when the naval steam ship HMS Orpheus crashed on Taramainuku’s net, the Manukau Bar. The long, narrow format of the footage suggests that we are viewing these scenes from within the lighthouse at Āwhitu, or peering through the lookout slots cut into Grande Folly Egmont.

Moving-image still from Manukau showing remains of the HMS Orpheus shipwreck.

Online references commonly describe the wrecking of HMS Orpheus as New Zealand’s worst maritime disaster. Of the 259 naval officers, seamen and Royal Marines aboard, 189 died. The wall label tells a slightly different story, however, turning this language on its head to declare this event to be Taramainuku’s greatest victory during the Land Wars. It’s a discreet shift in the narrative that demonstrates the importance of Indigenous curatorial roles within institutions, providing perspectives that would otherwise be missed in the story of our art and nation.

In another moving-image work, Ohawe, Brett recounts a story about a tōhunga from the Aotea waka who summoned a sand cloud from Hawaiki to soften the rocky Taranaki coastline in order to make a safe landing place for waka. Ironically, there are storm clouds brewing again, with iwi fighting mining companies to prevent these sands from escaping overseas, this time for steel production. These dramatic scenes are matched with an equally dramatic soundtrack, resounding with a deep bassline produced by sound artist Daniel Campbell-McDonald.

The past can be an ugly place, and lessons learned often need to be drawn forth with an awareness of time, context and changing attitudes

The standout work in the exhibition is undoubtedly Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata, a mobile pātaka of sorts that resembles a wooden horse-drawn carriage, or possibly a double-barrelled military tank (Graham has been known to carve military vehicles in the past). Carved wooden panels with distinctive Taranaki tuare (blind eel) serpentine figures encase the entire surface of the structure. Coated with powdered graphite, the entire sculpture shimmers like the black-sand shores here on the west coast. There is a lot to draw out from this work about the economics of cultural capital and the legacy of Māori dislocation and dispossession from resources and stores of wealth. Conversely, it is also a tribute to the industriousness of Māori communities, who were supplying Pākehā settlers in New Plymouth and elsewhere in the country with food and supplies in the years leading up to the Land Wars, amassing significant wealth and economic power in doing so. In the years since then, culture has necessarily become a mobile commodity, contorted by the machinations of capitalism.

Visitors negotiating O’Pioneer at the top of the Govett-Brewster stairway. Purutapu Pōuriuri, Black Shroud carpets the stairs below.

I’m reminded of Anna-Marie White’s excellent introductory statement, “The landscape is marked by monuments that open portals through time and cast the lessons learned by our ancestors into the future”. The past can be an ugly place, and lessons learned often need to be drawn forth with an awareness of time, context and changing attitudes. As a Māori artist and educator, Brett Graham creates new monuments and recasts the old with narratives that better vocalise the realities of our past, present and future.

The epitome of this is O’Pioneer, Graham’s monument to a monument. Adorned in relief-carved patterns derived from Victorian wallpaper, the sculpture is based on a World War 1 memorial in Mercer and a New Zealand Wars memorial in Ngāruawāhia that repurpose real gun turrets used on British war ships during the invasion of the Waikato in 1863. The memorial in Mercer faces Te Paina Pā where Te Puea Hērangi led anti-conscription campaigns, and the memorial in Ngāruawāhia sits on the pā site of Māori King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero at the intersection of the Waipa and Waikato Rivers. For the uninformed these sculptures may seem innocuous, but knowing the deathly carnage that these gun turrets inflicted locally, the memorials are a continuous slap in the face for Māori communities living with this legacy of unjust confiscations, brutality and murder.

There is a wedding-cake feel to this work, and the symbolism of a white wedding is not inappropriate, given the whitewashing of history that has occurred since Māori entered a relationship with the Crown. In subversive retribution, the stairway below O’Pioneer has been carpeted with patterned black velvet that features flags and insignia used by British soldiers. This artwork, Purutapu Pōuriuri, Black Shroud, sees visitors walking on symbols of colonial power, an act that could be cause for serious offence – as with Diane Prince’s infamous work in Korurangi: New Māori Art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in 1995, which urged people to wipe their feet on the New Zealand flag. It is hard not to also mention the kerfuffle accompanying ‘that show’ at Mercy Pictures this past year, thinking through careless cultural insensitivity in a gallery context versus Brett Graham’s defiant use of flag symbolism.

Visitors walking on Purutapu Pōuriuri, Black Shroud, which carpets the stairs leading up to the first mezzanine-level gallery.

This is one of those shows that sticks with you long after you exit the gallery. After visiting the exhibition, we found ourselves compelled to personally confront these histories, visiting sites associated with the Taranaki wars. Most powerfully, at Taranaki Cathedral, Church of St Mary we saw the gravestones of Pākehā soldiers “murdered by Maorie rebels at Waitara”, with one solitary grave for Waikato rangatira hidden away in the furthermost corner of the cemetery. Inside the Cathedral, hatchments of Crown forces who fought against Māori in the Taranaki and Waikato wars are still proudly on display.

For generations people have lived their lives with the narrative of these memorials informing their sense of history and identity. These and other monuments commemorating the founding of colonial nations have historically privileged settler heroes and narratives, belying a subtext of imperialist white supremacism that often goes unnoticed by audiences who are not attuned to the realities of Indigenous experiences.

As the recipients of this legacy, we inherit the land and the histories attached to it. But like the urupā on the hill above our whānau land, sometimes it feels as if Indigenous histories are being squeezed out, as the land is continually overlaid with new stories. The settler narrative is deeply entrenched in the physical landscape of this nation, but Indigenous artists and curators are working hard to rewrite the narrative to show the land as it truly is: complex and layered with multiple stories. The past needs new authors and I applaud Brett Graham for his monumental achievement.

1 Edward Hanfling, “Artist, Activist, Affect Alien: Diane Prince and the Flag Controversy,” Art New Zealand 159 (2016): 66–70.

Brett Graham: Tai Moana Tai Tangata

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

5 December 2020 — 2 May 2021

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Main image: Installation view of Maungārongo ki te Whenua, Maungārongo ki te Tangata with the peak of Cease Tide of Wrong Doing, Taiporohēnui visible on the right and Manukau behind.