The Len Lye Centre: A Pilgrimage

Leo Thomas makes a pilgrimage to New Plymouth's Len Lye Centre in memory of his uncle, who always wanted to visit but never made it.

Leo Thomas makes a pilgrimage to New Plymouth's Len Lye Centre in memory of his uncle, who always wanted to visit but never made it.

My uncle died last year. He had plans to visit the Len Lye Centre. He never got there.

I have fond memories of my uncle. He was the oddball of our family: wildly creative and unpredictable, always cracking jokes. He was the only member of my family to go to art school.

He saw value in things that others considered frivolous – things like stop-motion animation and mechanical toys.

I’d always looked up to my uncle so the fact that he’d been interested in the Centre was reason enough for me to go. Finding myself an unemployed writer at loose ends, I packed my bags. I was going to the Len Lye Centre – for my uncle.

It was a grey day for a pilgrimage. I set off from the cottage where I’d been living as a hermit. A residence with all the modern conveniences: a complete lack of insulation, zero internet coverage and a full HD fireplace. I'd been inspired by writers and creatives who had spent time in isolation: Salinger and Thoreau. My uncle and Lye.

I'd read that Lye had lived in a lighthouse. Maybe he'd get me.

I was travelling 300 kilometres, from a small town near Dannevirke, across the North Island to New Plymouth, my recently appointed holy land. There I’d find my temple of worship: The Len Lye Centre. My uncle was delighted when he heard about the Centre built in the artist’s memory. It seemed only fitting to visit it in his.

Lye had wanted to create a “temple of art”, the Centre being the posthumous realisation of this desire. It was to be a building that would, according to Lye, “symbolise the human spirit as effectively as a cathedral”. Not being a fan of the whole God thing I figured a temple of art was as good a destination for a pilgrimage as any – art being a three-letter word with which I had some affinity.

The sun came out as I was driving through Dannevirke, filling me with vague optimism. I’d decided to fast for the duration of the journey. Every major religion has both fasting and pilgrimage traditions, so why not combine the two? I thought abstaining from food might increase the likelihood of some sort of profound spiritual realisation. That, and I was pretty much broke.

Woodville came with lower back pain and self-doubt. Why am I doing this? It's not like my uncle’s going to care either way. On through the Gorge. Then Ashhurst. An eight-hour round trip to look at a building… what am I doing with my life? I stopped for gas in Bulls. I hadn't eaten since the night before, and hunger made gas station food seem a rare delicacy through glass display cases.

I thought about what it might mean to do something in someone's memory – for the centre to be built in Lye’s memory, and me to make the pilgrimage in my uncle’s. Wasn’t it just a way to abate a sense of loss through some weird extension of the grieving process?

On through Whanganui. The sun set golden over State Highway 3.

I stretched my legs in Waverly and did some pull ups for my back. Trucks rumbled through the town as I peered into a local artist’s showroom of intricate flax works. The clock tower chimed.

My uncle had been a huge fan on Lye. He and his wife had attended an exhibition years earlier. The curator had set a small collection of Lye’s work in motion just for them.

On through the Shakespearean affectation of Stratford. Then Inglewood.

Darkness descended on the highway as orange lingered on the horizon. Stars emerged and red taillights burned bright in the dark.

The Centre was closed when I arrived. It stood magnificent in the night – otherworldly.

The curved mirror of the steel exterior glimmered in the city light.

I walked to the waterfront to see the Wind Wand, a sculpture by Lye, a skinny 48-meter tall antenna-like structure that bends in the wind. Atop the wand sits a dome filled with light-emitting diodes.

I’d just been texted by an ex-girlfriend out of nowhere. My breath hung in the cold winter air. The wand bent and I shivered in the breeze. Lying down on a hard wooden bench I stared up at the glowing sphere, red like so many taillights in the dark.

I returned to my car to sleep and question my life choices.

I went to the Centre when it opened the next day.

It was beautiful in the light, bright and reflective. I entered the building and greeted the staff nervously, unsure what to expect, how to behave.

Ominous ambient music and metallic clanging came down a hallway. The interior of the building was like something from 2001: A Space Odyssey – stark and futuristic, perhaps vaguely oppressive. Utilitarian yet stylish, polished and clean.

I followed the ascending hallway in the direction of the discordant tones. Rounding the corner I encounter Lye's Four Fountains, and was immediately overwhelmed by their scale – and surprised to realise they were the source of the metallic clanging.

I sat in this room for quite some time, with the sculptures and the ambient tones. I found the environment soothing, alone with my thoughts and these colossal kinetic sculptures. The metallic sound from the clashing spines of the fountains reminded me of the resonant bowls of Buddhist monks. Not the sound itself, but because it focused my mind on the present. Atonal orchestral voices permeated the space, the mood meditative and introspective. I had reached my temple.

As I sat there, a friendly staff member informed me of a screening of a Lye documentary in the onsite cinema, the theatre with its red leather seats equally Kubrickian.

I discovered Lye's accent reminded me of my uncle’s, which made sense: they were born in the same city. The documentary spoke of his interest in motion – about how he had wanted to create a new style of art based on movement. This art of motion came to fruition through his animations, films, and kinetic sculptures. He thought of himself as composing movement like a musician composes music. His fascination with motion, and his sculptures, somehow reminded me of my uncle's mechanical toys. They hadn’t been made of plastic like mine. Like Lye’s sculptures they were made of metal. Cool to the touch. Heavy. They whirred and clicked.

Lye’s art, like a mechanical toy, evokes a certain child-like wonder. A fascination with the novel, the unique. In Lye’s words: “The muse of motion has a knack of arresting and holding attention… children are not bored while she’s around.”

Mechanical toys, sculptures that move. Such things could perhaps be dismissed as trivial, but I don’t think they are – they enliven the imagination. They bring joy.

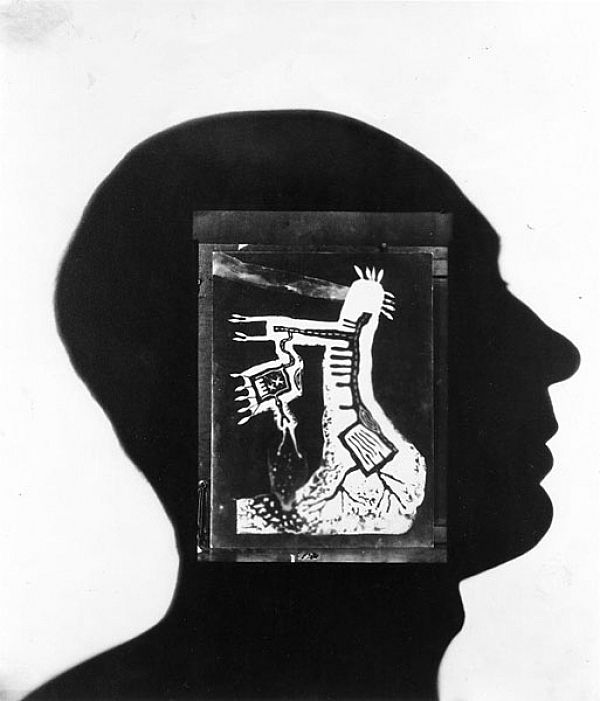

I continued to the current exhibition at the Centre: a collection of cameraless photography. Many of the works by Lye had been created by laying objects and people on photographic paper and exposing them to light, producing ethereal silhouettes and portraits.

By now it was afternoon, and I hadn't eaten in around 40 hours. I broke my fast a block from the Centre at a restaurant called Laughing Buddha. My pilgrimage was over.

I stuck around in New Plymouth for a few days, a ghost in a town where I knew no one. I’d planned on seeing the sights, but mostly I just hung out in the library. I read about Lye. I watched YouTube clips of his sculptures and animations, and I kept being drawn back to the Centre. I wanted to understand the man my uncle admired.

I was sad to leave town. I would have liked to return to the Centre again and again, to contemplate the camera-less works, the architecture, and to bask in the ambiance of the fountains. There were times during the day when you could be alone in the gallery, with those works from another world.

The Centre looked different depending on the time of day, but I felt it looked best in the warm light of evening, as the sun sets, when the air has a certain chill.

I wasn’t sure if my pilgrimage had been a success. I hadn’t experienced any spiritual awakening, and there was no revelation or life-changing epiphany. But I’d learnt that Lye was like my uncle in a lot of ways. They were both creative, artistic and eccentric. Both were craftsmen who worked with their hands, both proponents of the unconventional.

I drifted apart from my uncle in his later years. I was always meaning to get in contact, always meaning to visit, but I never got there. Like Lye, both my uncle and I loved film, animation and art. We would have had things to talk about. I had plans to get in contact, to return that email, just like he had plans to visit the Centre. But I never got there.

I drove down the highway. A distant Mount Taranaki, shrouded in snow, glowed blue in the cool evening light.