The Last Sober Driver

Mohamed Hassan on creating our own spaces, and the beauty of inviting people in. An extract from his new book: How To Be a Bad Muslim.

I have never drunk alcohol, but I have thought about it. I often wonder what it would taste like, what place it would take me to. Would it elevate me into gleeful lightness, or trap me in the depths of my own darkness?

Once, my best friend in high school lashed out angrily at my repeated refusal to engage.

‘You think this makes you a man ’cause you don’t drink? It doesn’t.’

I didn’t take his bait, but weeks later, in a school assembly about the dangers of binge drinking and peer pressure, I felt a hot indignance swelling inside me, and hoped my friend was listening and feeling ashamed.

It wasn’t a difficult choice for me. It was simply outside the realm of my allowances as a Muslim — back when the world was a thin straight line and good and bad were binaries. Now I’m older and adulthood is a flat weave of complexities. I have more Muslim friends who drink than those who don’t. It is not something I judge them for, though I can tell they feel judged by my mere presence. To walk into a party as a sober Muslim is to turn on the lights suddenly at a rave. You feel like someone’s dad showing up to drag his son out by the collar to an uncertain fate. My own dad practised discipline through silence, like a monk who refuses to answer your questions about the meaning of the universe, until one day you are screaming in desperation at an unrelenting sun and suddenly you come upon your truth.

I have never drunk alcohol, but I have thought about it

In the same way, I too use silence as a weapon, even if I don’t intend to.

Whenever I enter a space where alcohol is present, everyone gets uncomfortable. First comes surprise: ‘Why not?’ Then it turns into confusion: ‘You never drink? How do you have fun?’ Next it becomes interrogational: ‘So you’ve never even had a sip of beer?’ Finally, comes bargaining: ‘Just try it, bro, I won’t tell anyone.’

If you’ve ever been to a Muslim wedding, you know we don’t need alcohol to cause a riot. I have sweated through three-piece suits dancing for hours with Arab uncles re-living their youth, holding two breadknives between their fingers and swinging their hips to the beat. The heat from a hundred bodies soaking into the ageing wooden beams of a community hall that will air itself out in time for Sunday school the next morning. I’ve danced until the bride’s family was gone and I was left packing up the chairs. We’re crazy enough without the liquid courage. We turn up at the drop of a hat.

Remember the Arab Spring? Completely sober. The anti-Islam film riots that paralysed Sydney in 2012? Sober.

Remember the Arab Spring? Completely sober. The anti-Islam film riots that paralysed Sydney in 2012? Sober.

That video by rapper M.I.A. with the Saudi teens driving Range Rovers on two wheels while screaming with their heads out the window in the face of all logic and reason? Yup. Sober.

But at a house party in Mount Eden surrounded by bodies swimming in their own stomachs and telling you they’re having a great time — I get nervous and quiet. I don’t belong here.

Growing up in a country that loves its drink was difficult.

Every social interaction seemed hinged on alcohol, from high school parties to office functions to networking events to open mics. Everyone I met felt guarded until alcohol opened them up. Workplace friendships were formed at Friday-night drinks. Romantic pursuits seemed only conceivable when both parties were loose enough to be vulnerable. Evening television slots were a cocktail of jovial Tui beer ads about enjoying the summer with the boys, followed by grim drink-driving ads touting the now famous slogan: It’s not the drinking, it’s how we’re drinking. Was it really not the drinking?

Christmas parties were the worst

Christmas parties were the worst. It’s almost an unspoken social contract that it’s the one day each year where no limits are abided. No one needed to be at work the next day. Everyone was drunk enough to not pay attention.

Everyone except this guy.

I would remember every messy thing that happened, every racist thing that was said, each awkward romantic gesture left unrequited on the office floor. I was the silent witness to all of it, and as a result no one trusted me.

My friend Carrie Rudzinski wrote about the experience of being the only sober person at a party in her poem ‘Carburetors’. At least, that’s how I’ve always read it. It’s one of my favourite poems.

There is no leaving now: only the nausea of coming and going, a breeding ground of answers that don’t stand for anything.

In the innocent summer of 2012, Kendrick Lamar released his breakout single ‘Swimming Pools (Drank)’, catapulting him from a prophesied Compton rapper that hip-hop heads were excited about, to a sudden staple at North Shore parties. I once had the misfortune of being stranded in a corner of a stranger’s living room after a theatre show, watching a pack of White kids yelling every word to the song’s vital hook, making sure to annunciate the n-word in the first line while they raised their Heinekens to the ceiling.

They seemed to miss the irony that the song was actually about alcoholism and peer pressure, but then again, so did every club in the world that year.

I went to see Vince Staples play the Powerstation a few years later, and left reeking of other people’s pints and cradling the unshakable memory of watching hundreds of middle-class White men chanting: ‘I ain’t never ran from nothing but the police.’

After parties and gigs, I would throw my clothes into the wash before my mum could smell them

After parties and gigs, I would throw my clothes into the wash before my mum could smell them.

I have often wondered if I was missing out on an integral part of culture, if I was keeping myself on the sidelines of acceptance. Maybe this was the reason I often felt like an outsider. There were advantages, of course. I saved money each weekend, never having to fork out the costs at bars and restaurants. I’ve also never had a hangover, though my inherited migraines and natural sensitivity to bright lights have given me an insight into what they might feel like. Why would anyone willingly do this to themselves?

In the first Islamic teachings, alcohol wasn’t immediately ruled out. Much like modern-day New Zealand, pre-Islamic culture in Arabia saw plenty of drinking. It was one of the few pastimes nomadic tribes had to stave off the harsh realities of desert life — the long unruly summers, the cripplingly cold nights. Early Arab poets wrote odes to alcoholic drinks. Each region had its own brand, made with everything from anise in the Levant to grapes in Turkey.

In the first Islamic teachings, alcohol wasn’t immediately ruled out

Ancient Egyptian pharaohs traded in it, indulged in it during rituals and celebrations, and exported it to the rest of the world. It’s said that beer was originally invented by the Egyptians, an accidental byproduct of the agricultural revolution circa 10,000BCE.

When the Quran was first revealed to Prophet Muhammad in the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia, there were no requirements for how to be a Muslim except for belief in a single god. The act of worship itself wasn’t outlined until ten years afterwards, when the prophet and those who followed his path were driven out of Mecca and sought refuge in Medina, where he and Islam were embraced. From here, the tenets of what it meant to be a Muslim were slowly outlined.

Once the daily prayers became widely practised, a passage was revealed urging believers not to pray in a state of drunkenness, so that they could comprehend the words they recited. Alcohol was embedded in the culture — it would take a while for followers of the new faith to be weaned off it. Another passage spelled it out in more direct terms, explaining:

They ask you about wine and gambling. Tell them, there are great harms in them, [even though they bring] some benefit to the people, but their harmfulness is greater than their benefit.

Later verses would clearly forbid the drinking of all intoxicants, leading to the near-eradication of alcohol across the Muslim world. Of course, cultural practices survived in many of these places. Today you can find long-established bars in Istanbul side by side with ancient mosques. In Iraq, the large Christian communities continued to produce alcohol, and many of the pre-war middle class enjoyed drinking as part of their social fabric. In Egypt, steep import costs on foreign produced alcoholic drinks prevented their spread through most of society, but cheaper, often illegally made substitutes now fill social events and weddings even in the poorest areas of Cairo.

More religious families and communities still practise total avoidance, and many Muslims consider it a sin to be in the presence of alcohol, even if you don’t partake in it yourself. I’ve dragged my parents to countless poetry events and theatre shows where they sat politely while everyone around them drank, then escaped immediately after the show was over. Inevitably there were times that someone had too much and the mood of the place began to darken. They never complained, but warned me about spending too much time in spaces like these.

One day I told my friend Viv that I was going to quit poetry

It made me feel guilty — knowing they’d come to support me despite feeling uncomfortable in such a foreign environment, clearly outsiders. I often felt this way too, but persisted because I had nowhere I could be myself, where there was a stage and a microphone and people willing to listen. I was transformed there, unbuttoned.

But I still felt like a constant outsider, bartering parts of myself each time I needed to speak. One day I told my friend Viv that I was going to quit poetry. That it had served its purpose but I’d grown tired and needed to move on. I’d signed up for a youth poetry programme, but I would go to the audition the following day and hang up my boots. Put down my pen.

In those workshops I found a particular tribe, a group of young men I became especially connected to: Brian, Husam and Rewa. We were drawn together by a love of hip hop and an unspoken cultural overlap. We were Egyptian, Burundian, Syrian and Māori

The next day, however, I walked into a room full of young poets from all ages and backgrounds. They spoke truths I grabbed on to. They had an awkward confidence I vibed with. The workshop was run by a group called the South Auckland Poets Collective, made up of social-workers turned-wordsmiths who specialised in building life rafts for young people like me. Grace Taylor, Jai McDonald and Dietrich Soakai were the first of the group I met, and they ushered me in with open arms. I felt seen and acknowledged for the first time, and this moved a muscle within me that had never experienced the love of motion. The programme was run by young people for young people, without alcohol, filled with words. My plan to quit poetry evaporated. I had arrived at last. I belonged.

In those workshops I found a particular tribe, a group of young men I became especially connected to: Brian, Husam and Rewa. We were drawn together by a love of hip hop and an unspoken cultural overlap. We were Egyptian, Burundian, Syrian and Māori. We understood each other’s necessities. We understood exclusion, and we wanted to build something new.

We understood exclusion, and we wanted to build something new

A few months later, we started organising shows in neutral spaces — libraries, cafés, lecture halls, churches — and to our surprise, people from our communities started filling them. Our parents came. Our younger siblings and their friends. Other Muslims and Polynesians and Africans and kids who couldn’t legally get into bars, and others who just didn’t like being in them. It was eye-opening and beautiful. Something was shifting.

I had only thought about people from my community. I hadn’t considered that there were other communities which felt excluded from spaces that served alcohol; other people who felt unwelcome in them because of their age or appearance or religion or temperament. By creating a space without preconditions or assumptions, the way Grace and Jai and Dietrich had done for us, we filled it with our own energy, and people were drawn to it.

A few months later, we started organising shows in neutral spaces — libraries, cafés, lecture halls, churches

At the second show we held, we invited a musician to play too and ordered pizza for everyone. It was a very ‘youth group’ kinda move, but it meant that people were fed — another cultural tenet we held close to our hearts. If people were fed, their bodies would be at rest and their souls would be open. The poetry was almost an afterthought. It was an offering to the people who filled our space, and in return they offered us their energies. There was a magic to this that is hard to describe, but was always felt. When I invited new people in, they felt it too. It was a sacred exchange, a spiritual network we were building together. People left feeling full, connected, at peace.

This is not a commentary on alcohol — it’s about the intentions we invest. The power we have to create our own spaces, and the beauty of inviting people in.

This is not a commentary on alcohol — it’s about the intentions we invest

After these shows, all of my energy was spent. Driving away, the car would be packed with mic stands and papers and empty pizza boxes and a box full of cash which would go straight back into paying for the venue, and the chairs, and the lights and the musicians. When I got home, I’d sit in the quiet with the ignition off, push the seat back and close my eyes.

I’d poured out my insides to a room full of strangers, but had returned a vessel filled to the brim.

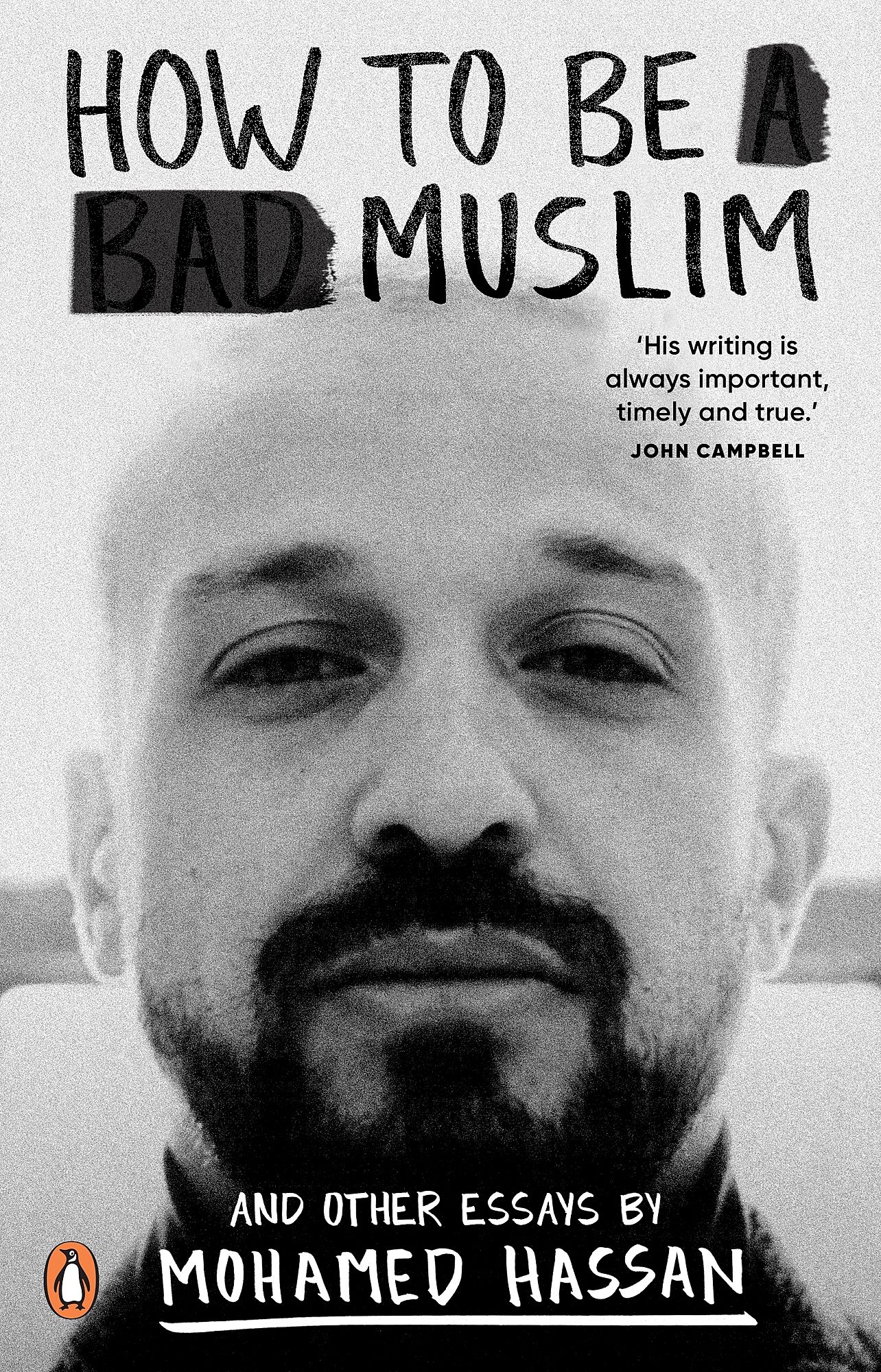

'How to be A Bad Muslim, and Other Essays'

How To Be A Bad Muslim is published by Penguin Random House New Zealand.

You can purchase copies of the pukapuka in local bookstores, or over on their website.

You can also see the author in person at these upcoming Auckland Writer's Festival events:

How to be a Bad Muslim: Mohamed Hassan

Sat 27 August, 2022

Tickets $12.50 – $25.00

The Baddest Art Friend: Chapman, Reilly, McInnes (chaired by Hassan)

Fri 26th August, 2022

Free Event