The Last Regional Theatre: Inside Centrepoint's Fight to Stay

Baz Macdonald talks to the people fighting to keep Palmerston North's Centrepoint Theatre alive about how, and why, they're fighting.

In Palmerston North, New Zealand's last provincial theatre is under new management and fighting to keep its head above water. But does it even matter if the theatre drowns? Baz Macdonald looks at what Centrepoint Theatre is doing to stay buoyant and make its voice heard.

On the morning of 1 May, Dunedin and the wider theatre community woke to the news that Fortune Theatre would be immediately and indefinitely closed, after 44 years of service.

This announcement was one Dunedin theatre-goers and practitioners had been fearing for years. But with the theatre’s staff and board giving no indication that things were so close to the brink, it still came as a huge shock to many – including Kate Louise Elliott, general manager of Palmerston North's Centrepoint Theatre.

“[Fortune closing] has made it very real to us,” Elliott tells me. “I am just so angry – it is another theatre closed, and I don’t see new ones popping up."

Centrepoint Theatre has been at the heart of Manawatu culture for 44 years. Centrepoint provides the region with a mix of international and national shows and, over its history, has established a tradition of staging locally written plays that spotlight the culture and people of the community – many of which were penned by Centrepoint’s 18-year-veteran creative director, Alison Quigan.

Centrepoint is now the last remaining professional theatre in the regions and it is fighting for its life. At current levels of funding, the theatre is just scraping by – if it doesn’t fold, it's likely to simply burn out. Jeff Kingsford-Brown, the theatre’s previous creative director, described it as “the slow strangulation” of the theatre.

"We can throw blame in all kinds of directions," Elliott says, "but when it comes down to it, we are just not given the resources to cope. So, I am thoroughly angry.”

Unfortunately, the demise of Fortune as a regional theatre was not an anomaly – the situation for Centrepoint has been just as tenuous over recent years, and Elliott says that despite an uptick in sales so far in 2018, the community should not get comfortable.

If Fortune is any indicator, an uptick is not necessarily a sign that things are all clear – a statement from Fortune Board of Trustees Chairwoman Haley van Leeuwen says tickets had been declining for the Fortune since 2012, but that 2017 had shown an uptick in sales. Yet, despite this, 2018 marks the end of the theatre’s 44-year journey.

“People in the community have been asking me, ‘Will that happen here? Could we wake up one morning and hear that?’,” Elliott says. “I tell them, ‘Absolutely! We are always only two shows away from closing.’ But we are working our darndest to make sure that doesn’t happen [here].”

The past five years have been particularly hard for Centrepoint. Following the implementation of two new funding models, the Toi Tōtara Haemata and Toi Uru Kahikatea Investment Programmes, support from Creative New Zealand dropped by $85,000 a year. That took the theatre’s annual CNZ funding from $495,000 in 2012 to $410,000 in 2014. This was further exacerbated by a 2016 drop in CNZ revenue from the Lottery Grants Board, resulting in a further 10% drop in the theatre’s funding.

The Centrepoint management at that time were vocal about the challenges these funding cuts presented to the theatre. In 2014, then-Administration Manager Julie Barnes said to the Manawatu Standard, "The basis of funding from Creative New Zealand is not fair for this community. You can't compare us to other theatres when we are the only professional provincial theatre in New Zealand."

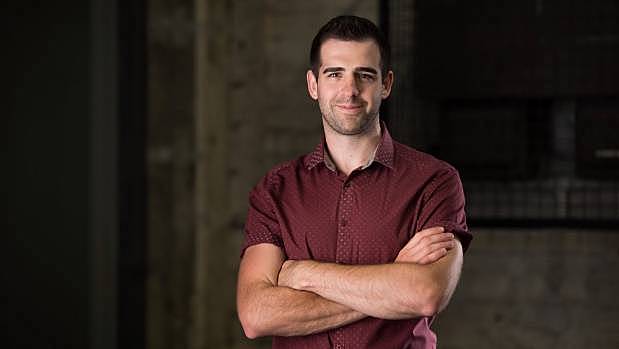

Centrepoint has a new team – Dan Pengelly was appointed as creative director in February 2017 and Kate Louise Elliott joined as general manager later that year. Their fresh energy and enthusiasm is the reason they have had a strong 2018 so far, Elliott says, but they are far from out of the woods, because the theatre’s audience numbers were “not good” last year. “We are in trouble. We need to build our audience numbers significantly.”

Even then, Elliott doesn’t know how sustainable it is to work her team this hard, and for so little money. “I have to ask my staff to work 200% on 30% wages. I have to say, ‘please do it, so one day your grandchildren can still come to the theatre.’

“But, when does it become too much? When does it become so hard, for everybody to go ‘I just can’t do this anymore’? We are getting sick. We are getting tired.”

“People in the community have been asking me, ‘Will that happen here? Could we wake up one morning and hear that?’,” Elliott says. “I tell them, ‘Absolutely! We are always only two shows away from closing.’"

Elliott has a long history with Centrepoint, having previously worked as the theatre’s artistic director from 2008 to 2012. In her time, Elliott has seen the theatre on the brink of closure “so many times.” But each time she had brought it back, calling in every favour she had to do so.

“We should be setting the standard for professional performing arts in the Central North Island,” Elliot tells me. “We should be touring to regional centres. We should be the development hub for new works and artists in this country. We should be training everybody and giving everybody a go.”

What’s stopping them? “When it comes down to it,” Elliott says, “[theatres] are just not given the resources to cope.” For Centrepoint to survive, the answer is simple: “We need more funding. We need more resources to be able to fulfil what we could be.”

These are among the most important reasons that professional regional theatre needs to exist in New Zealand, yet there are just not enough resources available for the theatre to fulfil all of what they could, and should, be.

The root of the problem, Elliott says, is an expectation from the government that theatres should be able to function as financially viable, sustainable businesses. The public and government need to “stop making us try to be businesses,” she says, “Because we are not! We are the arts. And if you want to have arts, you have to pay for them.”

The discussion of additional funding for the arts inevitably draws the question from some members of the public, “Why should we fund the arts?”

“Sure, but then ‘Why should we fund the rugby?’ or ‘Why should we fund this or that?’ There will always be that rhetoric,” Elliott says. “I had a person years ago in the foyer of Centrepoint confront me with the question, ‘How do you keep trying to get money from the council when you have a hospice down the road?’ I’m not in competition with the hospice, because in government there are different budgets.”

“When [the government finally turn[s] around and accept that art is a necessary component of making a liveable country – when we want to grow our art – then we might finally be able to get somewhere.”

The New Zealand theatre industry is wholly reliant on external funding sources, primarily from Creative New Zealand. CNZ, in turn, ask that theatres generate 60% of their operating costs from a combination of corporate sponsorship, box office and other forms of fundraising.

Yet there is a free market rhetoric in our communities at large that if a theatre cannot operate as a sustainable business, then perhaps it shouldn’t be operating at all. But even if New Zealand theatres could operate as self-sustainable businesses, which seems unlikely considering our population size and density, Elliott says it is hard to find people with both business acumen and a desire to work in a low-income industry such as the arts. “If you’re really good at what you do as a businessperson, are you really going to take a job in the arts?”

Rather, management and business roles often get filled by people like Elliott, who went to drama school and moved into these roles simply out of the desire to contribute to the arts. For small theatres such as Centrepoint, this creates a gap in skillsets like marketing, requiring those theatres to hire or enlist outside consultants. Again, though, there isn’t the money necessary to contract these people.

“We can’t afford big budgets to get in the face of the public and show them what is happening. We can’t afford top-of-the-game marketing managers to come in and do a campaign. We can’t afford for amazing business teams to come in and [manage the business side of the theatre],” Elliott says. “We rely on people who have those skills to assist us and help out. But that is luck of the draw and something that is not sustainable.”

Even traditional business approaches, such as property ownership vs renting, have unique perks and pitfalls in the theatre industry. For instance, Fortune Theatre hired its space from the Dunedin City Council, which was a huge financial sink for the organisation. Centrepoint, on the other hand, has the advantage and asset buffer of owning their own buildings. They are the only theatre in the country to own their own property. But that also has its downsides, Elliott says: “We can’t fix or refurbish anything, because we can’t afford to.”

A theme emerges: almost all Centrepoint’s problems come from a lack of funding and so, for the theatre to survive, they need more money coming in. But where is this extra money supposed to come from? Elliott thinks the solution is the Government budgeting more money for arts. “When they finally turn around and accept that art is a necessary component of making a liveable country – when we want to grow our art – then we might finally be able to get somewhere,” she says.

“Start giving us the weight that is needed, or you won’t have us.”

The 2018 Budget saw a slight increase of $6 million in appropriations for arts, culture and heritage, from an overall $237 million in 2017 to $243 million this year. Though it is not yet clear how this extra funding will be allocated, announcements from the Government indicate the New Zealand music industry will be the focus.

“Centrepoint became unfashionable at a point... [CNZ] came once a year and hated what we were doing, essentially. Seeing it as provincial – our choice of programming was seen as very low rent. There is a real cultural imperialism thing going on.”

Though it is a government department, Elliott doesn’t think Creative New Zealand are part of the problem. Rather, they’re simply an agency that does the best with the “minuscule” amount they are given. “I believe Creative New Zealand are our biggest arts advocate,” she says, “and there is a misconception within the industry of what their role is. People constantly go, ‘blame CNZ’ – but that is not correct.”

“CNZ get the money from the government and they do their best to set up systems and put things in place which allow theatres to find the funding they need. Of course, that is not going to be a one-size-fits-all, but they do the best they can.”

Elliott believes there is a misconception that CNZ are a financial safety net for theatres, and that the organisation will bail out a theatre in trouble. This means that there’s a perception from some in the industry that, when a theatre closes, CNZ are the ones to blame, she says. “But...[w]e can’t just go to Creative New Zealand [whenever we want to], they’re not mum! We can’t say, ‘Oh, hey, I can’t make my rent this week, can you cover?’ They have processes in place, through which they give out the minuscule amount of money they get.”

Creative New Zealand Senior Manager of Art Development Services Cath Cardiff says that although it is difficult to make theatre work in New Zealand under any circumstances, outside of Fortune’s closure the theatre sector is looking very strong. Cardiff says CNZ are funding “much more” under the Tōtara and Kahikatea investment programmes. “Some people are doing extremely well, and some not so well,” she says.

“Obviously, it is difficult in a small theatre and it is difficult in a big theatre for different reasons,” Cardiff says. “Speaking with Massive or Silo, you wouldn’t get them saying it is easy for them because they have so many people to sell to, because they are existing in a highly competitive environment.”

CNZ closely monitor trends in all sectors of the arts industry, and when things aren’t going well for an organisation they try to provide assistance and coaching so the organisation can handle the challenges facing it. “But every once in a while, despite everyone’s best intentions, it cannot be fixed,” Cardiff says. “It is as basic as expenditure exceeding income. If you can’t make that work, with all the sources of funding at your disposal, then you can’t make it work.”

Under the new Tōtara and Kahikatea investment programmes CNZ is giving much more funding to theatre, Cardiff says. Centrepoint is part of the Tōtara investment programme; however, it was under this programme that it saw its funding cut back.

Jeff Kingsford-Brown was the theatre’s creative director from 2012 until February 2017. He says the theatre was financially healthy when he started, but as those cuts took effect, “it became extremely difficult. It really started to affect us by the third year – we were struggling.” These cuts happened, Kingsford-Brown argues, because Centrepoint was “not quite how [CNZ] pictured a theatre company working.”

“Centrepoint became unfashionable at a point,” Kingsford-Brown tells me. “[CNZ] came once a year and hated what we were doing, essentially. Seeing it as provincial – our choice of programming was seen as very low rent. There is a real cultural imperialism thing going on,” he says of the situation. “They don’t like the whiff of audiences having a good time.”

“Honestly, I think, the loss of Centrepoint, to CNZ, would not be a major blow.”

In response to this, Cardiff re-emphasises that Centrepoint “add[s] to the cultural landscape, regardless of the programme. It is the reality that in a community, audiences want particular kinds of experiences. There is no cultural imperialism as far as that is concerned.”

Kingsford-Brown argues that CNZ believed Centrepoint was less deserving of funding because of the content that their audiences preferred: productions derisively referred to by some as “bums on seats” theatre. Centrepoint’s programmes are typically made up largely of pantomimes and comedies like, during Kingsford-Brown’s tenure, Dan Bain and Brendon Bennetts’ Stag Weekend, Alison Quigan and Ross Gumbley’s Boys at the Beach, and John Lepper and Simon Ferry’s Stock Cars: The Musical – high sellers, but considered by some to be not very creatively significant.

“We are not seen as being particularly innovative or ground-breaking,” Kingsford-Brown says. “We don’t bring anything to the party, except for our local audience.”

Elliott highlights the 2002 play Netballers, written by Alison Quigan and Lucy Schmidt, as an example of this. “These local productions certainly had important themes and issues in them. Alison would have meetings with the community and learn their experiences. She would find that hook of interesting things that had happened [in the community], and that would just happen to be around a netball court.”

CNZ are very interested in the artistic health of our country, Cardiff says, and are dedicated to building a portfolio of organisations that will make New Zealand a world leader in artistic terms. “If someone doesn’t bring anything new to the table, it is hard to get any funding at all. In any of our funding programmes it is highly competitive – in Arts Grants, for instance, only one in four proposals gets funded.”

“People have a hard ask in New Zealand and we think that is a good thing – our standard is very high, and so is theirs.”

Cardiff says that there are a wide number of factors to consider when allocating funding, including the way theatres build relationships with and represent their communities. “It’s not just about being new and innovative, though that is at the top of our minds,” she says. “It is also about the types of people that are engaging with that work, where they are based and how many are engaged.”

“Within that, there is the reality of viability in a small market. A theatre like Centrepoint services their community, they need to put theatre on that their audiences want to come to. We realise that.”

"...there’s a perception from some in the industry that, when a theatre closes, CNZ are the ones to blame. But...[w]e can’t just go to Creative New Zealand [whenever we want to], they’re not mum!"

Cardiff says CNZ welcome and encourage programmes which utilise all the different audiences in their area – with some of the country’s most successful theatres offering a programme of content that reaches a broad range of audience tastes and preferences.

“Some of those audience segments go to see plays that I personally wouldn’t care to go to, but they do, and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. It is a good thing. A diversity of audience and a diversity of product is what we are after,” Cardiff says.

Far more important to CNZ is the artistic quality of the content an organisation they are funding is putting on. “If someone was putting on plays that were poorly designed, poorly acted and badly cast, we might get interested in that. But we are very lucky at the moment, we don’t have that sort of thing happening,” Cardiff says.

While Jeff says during his tenure the relationship between the theatre and CNZ was not good, he adds it was probably because he wasn’t making a strong enough case for the theatre.

“I know Kate Louise is great at stating the case.”

With Centrepoint fighting for its life, and Fortune closed, what does that mean for the future of regional theatre in Aotearoa New Zealand?

The Fortune closing is a frightening development for the arts industry, but Cardiff says CNZ are motivated to see professional theatre return to Dunedin. “In the interim, that might mean more touring productions going there – we have levers that we can pull in that area. In the mid to long term, it will be how to re-establish the base of a professional theatre in some way.”

CNZ are committed to seeing theatre exist in all regions of New Zealand, Cardiff says, and are currently working on a new strategy which would see the arts bolstered outside of the urban centres and throughout the rest of the country.

“In the past, Creative New Zealand funding has been based on demand – so it is based on who applies, as opposed to us trying to establish a theatre in every town,” Cardiff says. “But, we have realised that if we just keep funding whoever asks, then most of the funding will end up in Auckland – that is just the reality of it – and we’re not happy about that. So, we are recalibrating, but I cannot predict what that will look like.”

As for Centrepoint, Cardiff says surviving as a theatre requires innovative approaches. An example of Centrepoint’s creative thinking is how it’s supplementing its revenue with a variety of performance education programmes, including a holiday programme and a junior and senior company. Cardiff points to these education programmes as the kind of innovative approach theatres need to survive.

“I would say that Centrepoint is doing, at the moment anyway, very well on that.”

Ultimately, the loss of Fortune is bigger than just one theatre – it is the loss of a cultural hub for an entire region of the country. Without the Fortune, Otago and Southland lose not just a destination for professional theatre, but also the organisation that would tour theatre productions throughout the region. As someone who grew up in Southland, the death of regional theatre would have meant a seven-hour drive to see a show. Would I even think about seeing a show if that were the case? If theatre was that far removed from me, why would I try to experience it?

Centrepoint fills the same role in the Central North Island that Fortune did in Otago and Southland. It’s a cultural bastion in the area, an organisation built and funded for the purpose of keeping professional theatre alive in the hearts and minds of the people of Napier, New Plymouth and the surrounding townships. Without Centrepoint, these cities could be in the same position as the people of Otago and Southland are now – with theatre too detached to be a part of their culture.

But that cultural bastion is in rough waters. Theatremakers and administrators in these regions, like Kate Louise Elliott, are telling us over and over again that the financial math of running a theatre in the regions as a business is just not sustainable. For these theatres to survive, it will require a fundamental restructuring of how we fund and practise regional theatre in New Zealand.

This week we’ve been focussing on the state of New Zealand theatres that serve the regions. You can read the companion piece to this, regarding the closure of Dunedin's Fortune Theatre, here.