The Friction in the Collection / Or, Ruth Buchanan Rubs up Against the Govett-Brewster

Ruth Buchanan’s 'The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong' marks the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s 50-year anniversary. Lucinda Bennett writes about the discomfort, and the sheer joy of discovery.

Ruth Buchanan’s The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong marks the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s 50-year anniversary. Lucinda Bennett writes about the discomfort, and the sheer joy of discovery.

The split and contradictory self is the one who can interrogate positionings and be accountable …

– Donna Harawayi

Let me set the scene. It is 1982, and the Govett-Brewster is the sole public contemporary art gallery in Aotearoa. You walk through the doors and are surrounded by artworks hung floor to ceiling. What seems like every single work from the collection is out, salon-hung for a truly maximalist exhibition experience. You soon learn that this is indeed the case: with the exception of a few sculptures and delicate works on paper, you are standing amidst the entire Govett-Brewster collection.

Titled The Great De-Accession Exhibition, this is no eccentric curatorial exercise. The exhibition has been mounted to give the public an opportunity to view the collection in its entirety, so an informed decision might be made as to which works are ‘relevant’, and should therefore be held onto.

This was – and still is – an unusual scene. The Govett-Brewster is unique among collecting institutions for a number of reasons. Having only opened in 1970, its collection is relatively young – and in more ways than one, given its lifelong mandate to collect contemporary art. Furthermore, unlike many of its peers, the Govett-Brewster was not borne out of a local art society and bequeathed a cumbersome collection. Rather, having been founded in 1962 by the forward-thinking Monica Brewster (née Govett), the gallery received a further endowment from Brewster that enabled the establishment of the collection in 1969. Developed by the inaugural director, John Maynard, the gallery’s founding documents outline progressive exhibition and collection policies, many of which stand to this day. Among these is a policy that allows the deaccessioning of any work, so long as it has been held for at least five years and a suitable reason can be given. Such reasons tend to boil down to issues of ‘relevance’ – but what does this mean?

Having initially proposed a project during her 2015 artist residency that would see her delve into the collection, Ruth Buchanan (Te Āti Awa/Taranaki) found herself more intrigued by the formation and the policies that structured the collection than the collection itself.

“I had just finished this collection project in Berlin, so there were lots of things I was thinking about around collection politics and how to manage the collecting of more challenging work, conceptual work, for instance, what do you do with scraps of paper? How do you keep the logic of the work? So I was imagining I’d be able to dig about more into that, imagining that the collection [at Govett-Brewster] would have more performance, sound work, challenging early installation, that kind of thing. Then, when I got here and looked at the database, it was a bit like… oh. There is a lot of Michael Smither here! And some of those are amazing works, but it just wasn’t what I had fantasised about, and I wanted to understand why I’d had such a different idea of the collection, and what was the spirit of the institution?”

Shouldn’t a gallery attempting to amass a contemporary collection be looking forward, rather than backward?

Her three months in New Plymouth were spent conducting a great deal of primary research into the gallery’s history to uncover how the policy had been written and utilised. Buchanan explains, “There was no timeline, and there was no real Govett-Brewster archive you could walk into to get the information quickly. It was all sort of scattered across scrapbooks and council notes and things. One of the things that was very interesting to me was this active deaccession policy, so I began to hone in on that, wondering whether that had been something that anyone at any time had utilised.”

It was through this research that Buchanan learned of The Great De-Accession Exhibition and its associated public forum, held by then Director Dick Bett. Following this forum, Bett recommended a streamlining of the collection to focus on what were perceived as its four ‘greatest strengths’: art from Taranaki, New Zealand sculpture, non-figurative painting and the work of Len Lye. In Buchanan’s 2016 exhibition, The actual and its document, each of these strengths was symbolised by a single work: Don Driver’s Five part piece (1972), Tom Kreisler’s The Key (Coat III) (1970), Greer Twiss’s Red Legs (1968), and by the Len Lye work in the adjacent gallery dedicated to showing his oeuvre.

The actual and its document was not the first time Buchanan grappled with the complexities of managing culture. Her work is often concerned with power, gently exacerbating and contaminating apparently benign systems of architecture and language to expose their sovereignty, the ways they work to control not only our bodies but our histories. When describing her work’s relationship to these systems, Buchanan often employs a vocabulary of illness and destruction: it is corrosive, contaminating, destabilising. It is important, however, that this vocabulary is also subtle: a structure can corrode for years before the ceiling gives way, a slow drip will eventually contaminate the whole reservoir, the Jenga tower may not fall until the last block is laid. There is an affective power in letting us figure out what is being signalled or what is missing – and perhaps there is another kind of power altogether in the possibility of the audience not recognising any problems, in our failure to notice that the four identified ‘strengths’ of the collection correspond to those identities that can see themselves most strongly represented in the collection.

I have so many questions, and it occurs to me that I am experiencing the subtle machinations of Buchanan’s work: this is research made material, made to act as a catalyst for the kind of questions without which we would have only the bland acceptance of homogeneity.

I can’t help but find this perverse, that the categories slated for further investment were those that had already found the greatest representation within the collection. Surely the status of these kinds of works was gained from such processes as being collected by an institution, or by multiple institutions? Wouldn’t it be moot, to continue collecting in this same vein? Shouldn’t a gallery attempting to amass a contemporary collection be looking at what was being made around them, looking forward, rather than backward?

I have so many questions, and it occurs to me that I am experiencing the subtle machinations of Buchanan’s work: this is research made material, made to act as a catalyst for the kind of questions without which we would have only the bland acceptance of homogeneity.

*

And so we find ourselves in a new scene. It is 2019, the 50-year anniversary of the Govett-Brewster. Commissioned by the gallery’s incoming Co-directors, Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, Buchanan has made another exhibition – her own Great Exhibition, perhaps. The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong builds on the groundwork laid by The actual and its document, working to activate the founding collection policy by interrogating its material consequences. It is, Buchanan tells me, “not my favourites from the collection, nor a canonical hang, nor the greatest hits.” Indeed, this exhibition disobeys the standard conventions of a collection show, such as choosing works based on a theme or centralised narrative, instead prioritising showing as much work as possible (within the parameters of the existing gallery architecture). “It’s a detailed excavation of the arc of the collection,” Buchanan says, “a way of opening up its mechanisms and making imbalances evident… it shows the priorities of those with power.”

The show is therefore arranged carefully, chronologically, with each space representing one decade in the history of the collection. Each space is then filled with the first work acquired per artist, per medium and per decade, divided into categories and arranged accordingly. Buchanan’s own, somewhat auxiliary, structural works codify the space. Some of the category labels are clear in their meaning; Living and No Longer Living seem evident, especially as they disappear in later decades. Others are more idiosyncratic, following a convention Buchanan had developed previously by borrowing category titles from German artist Marianne Wex’s vast photographic project Let’s Take Back Our Space (1977), a compilation of over 3000 photographs showing men’s and women’s differing body languages, revealing “the unconscious ways in which the patriarchy literally occupies more space” – an apt reference for a show that essentially reveals the same thing in the context of a collection.

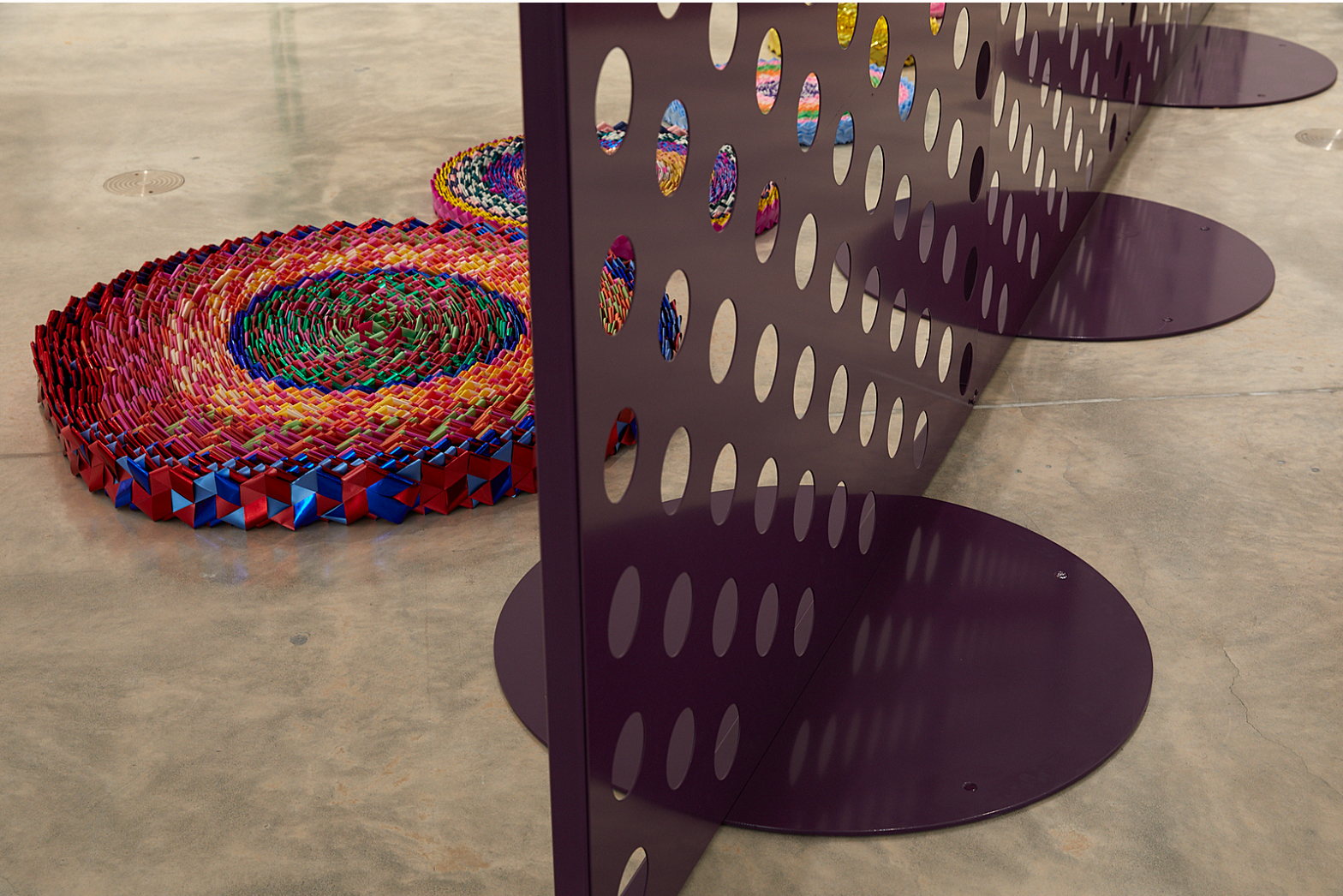

The 1970s, for example, spreads across the ground floor and the mezzanine. Eighty-nine artworks are presented across three unequal and opaque categories: 14 are by female artists, 69 are categorised as Legs, and 6 previously unexhibited works on paper are relegated to the vitrine for Exceptions. Dominating the 70s, the works in Legs are all by male artists, their limb-y category referring to the idea that these guys are “really going somewhere.” When we reach the 1980s, we are faced with a new selection of categories: Living (33 works), Body (5 works), No Longer Living (24 works relegated to the liminal space of the ramp), and Exception (2 works). This time, the exceptions are books, one by Minerva Betts, the other from The Estate of L. Budd, displayed in their own hospital-green vitrine (Care/Flood, 2019) mounted on the wall at the end of a tight passage created by two of Buchanan’s purple punched-metal screens (When the sick rule the world, 2019). They are bathed in the dappled light that filters through the screens’ circular holes, each one the size of Buchanan’s fist.

Despite the systematised nature of this exhibition, as I walk through the space I find that questions arise organically, bubbling through the walls. In the 1980s, next to the vitrine holding Betts and Budd yet separated by Buchanan’s perforated free-standing screen, three works huddle together, their accompanying wall caption reading “Body Work”. I have to flip through the many pages of Legs from the 70s to find these works in the exhibition guide, but there they are: Christine Hellyar, Cloak Cupboard (1981); Christine Webster, Domain – Paddy (1984); Janet Bayly, Female Nude I, Female Nude II, Female Nude III (1980). But then there’s more: Stuart Page, Piss Head (1982) and Andrew Drummond, Crucifixion performance (1971). But where are they in the space? The answer, it turns out, is tucked into the end of each work’s acquisition notes, included in the guide. Due to “the nature of the content” of Page’s and Drummond’s Body Works, they have been placed on display in the gallery directors’ office, where they are available to view by appointment. Who made this decision, I wonder? Did Buchanan’s system insist that these works be included in the exhibition, yet their controversial history (Drummond, for example, was charged with offensive behaviour and appeared in court following his 1978 performance) perhaps forbade their display? Did the directors put their feet down, or did Buchanan want a family-friendly show? When it came to the making of this show, who wielded the ultimate power of veto – the new directors, keen to make a good impression, or the Taranaki-born artist they had commissioned to develop an exhibition with intimacy and criticality? Where is power now?

By showing us where this collection has been, Buchanan has made space for us to question where it is going, to voice our opinions on where it should go, and to imagine what it would take to get there.

This, indeed, is the core question posed by Buchanan in her accompanying essay, the question that drove her approach to this project: Where is power now? However, those expecting to have this question answered by this exhibition may be left wanting, for it’s a show that reflects the period of questioning we are living through; not so much answering our questions about the role of institutions and the relevance of collections, but asking them alongside us and providing us with a material encounter to inform the decisions we make about this collection now. What will be the legacy of this era, of these directors, and of the next public forum, in which we are all invited to take part in 2020? By showing us where this collection has been, Buchanan has made space for us to question where it is going, to voice our opinions on where it should go, and to imagine what it would take to get there.

To my mind, it is the materiality that gives this show meat, the way Buchanan turns her research into something not only tangible, but affective. It is one thing to read the statistics of a collection – it’s another thing entirely to be surrounded by it, to feel what is present and sense the gaps, to look for things that aren’t there and discover things that are there of course, or are there against all odds.

Nowhere are these sorts of inclusions more apparent than in the largest and final gallery of the exhibition, the space dedicated to the decade that just ended. Here, Buchanan offers a question to the institution – or perhaps a challenge: Will the new directors continue to reach back into the past, collecting notable works from the 20th century, or backfilling the gaps to see greater historical representation of women, Māori, Pacific and other minoritised artists? Or will they continue to expand the collection into and around the Pacific, looking to what is being made by our close neighbours in Asia? If we were to redraw the four categories that would make this collection the most contemporary, or the most relevant as we move into the future, what would these categories be? Or is the lesson to be learned that categories, flawed as they have been revealed to be, should be dispelled entirely?

In their statement accompanying the exhibition, Burns and Lundh recount their own questions upon accepting their roles at the Govett-Brewster. “How could we … remain true to and complicate the institution’s self-image as an agitating, challenging, and contemporary artist-centred space that reflects the present and projects into the future?” It seems that, in bringing Buchanan in to do what they cannot, the directors have already signalled an intention to approach the collection critically.

*

During an opening-weekend talk, art historian and Adam Art Gallery Director Tina Barton reflected on another project of Buchanan’s, describing BAD VISUAL SYSTEMS (2018) as “absolutely present, but also absent.” A paradox, to be sure, but one that describes Buchanan’s most recent projects well. For all its punch and colour, Buchanan’s material presence is made up of background forms – vitrines, screens, plinths, labels, soft wall paintings – objects and gestures that set the tone of the scene rather than fabricating an entirely new one. Crucial to this effect – and to Buchanan’s self-positioning – is that her work always appears at the scale of art, not architecture. In doing so, she implicates herself as an artist, beholden to the same systems of power as those artists she has put on display, but also acknowledges the curious position of power she finds herself occupying in the context of this exhibition, and an acceptance of the responsibilities this comes with.

But what is her position exactly? Burns refers to Buchanan as an “interlocutor” for herself and Lundh as they step into their roles as directors, aiding their understanding of the institution, its holdings, its place in Taranaki and its place in Aotearoa – now and throughout its 50-year history. Buchanan views herself firmly as an artist, although in acknowledging the power she has over the other artists whose work she has put on display, she is also acknowledging the slippage into the role of curator. Indeed, during opening weekend talks and in my own conversations about the show afterwards, I found myself constantly correcting my use of the word ‘curator’.

But this is not a collection show curated by Buchanan, it is a project undertaken by an artist interested in the languages of collections and archives, and how these are presented. It seems crucial to me that Buchanan is an artist, not a curator. As an artist, she is not beholden to the institution in the same way as a curator, not required to maintain the story this institution has been telling about itself since its inception. Furthermore, as an artist, Buchanan’s priorities are different: she is here to destabilise, but she’s also willing to take responsibility for her decisions. While part of the goal in imposing a system onto the collection was to create an objective distance between the works and the institution that acquired them, she does cop to the fact that the categories she created are borne from her own mind, interests and experiences. She also readily admits that, in making a category titled Politics, she is determining what makes a work political through her own lens and pasting that label up beside that work.

To my mind, this is all part of what it is to really activate something like an archive. To be active is to be dynamic, incomplete, riddled with mistakes, in process. There’s red pen and crossed out sections on the page, the work is still under scrutiny. Buchanan references Audre Lorde’s notion of “scrutinising intimately”, and it feels like this is exactly what she’s doing, and what the exhibition is trying to make us do. Look at this collection, its contours and chasms! Get inside it, feel what’s here and what’s missing, the joy and the pain of it.

There is another aspect to a show being arranged by an artist. Works are hung in a way a curator simply would not hang them. It’s messy, noisy, loud, by far the most fun I’ve ever had viewing a collection show. There’s evidence of real pleasure taken in their object-ness, and how their object-ness interacts with the gallery architecture. I notice just how blocky some works are, how much they stick out from the wall, how stretching your own canvases means you end up with some really random sizes. Paintings butt up against one another, are hung snugly beside security cameras and electrical panels. The poster sheets of Judy Darragh’s Wild Thing (1999) are pasted up around an elevator door. It’s kind of like the approach I took to decorating my bedroom as a teenager: more is more – architecture is just shapes to be filled with pictures and personality.

This playfulness is borne from Buchanan’s dogged insistence on showing as much of the collection as possible: the show needs to be hung like a game of Tetris to fit so much in! – but it’s also what creates the sheer joy of discovery. To have your gaze pulled upwards by a previously unseen painting hung at a neck-craning height. To see so many works you’ve never seen before, minor works that are never pulled out, many by artists you know and love, but also plenty by figures unknown to you. Visiting the exhibition on opening morning, the gallery felt alive, filled with people of all ages peering and pointing at the walls, squinting at their guidebooks. I wish it weren’t such a novelty to be so excited – and to observe others who seem to share this sentiment – at a collection show, but I am glad to have experienced it here.

*

Or, where does my body belong?

‘Embodied’ is a term we love to throw around in contemporary art, and often the criticism comes – what are we, if not embodied? We have bodies, don’t we? How would we even make art and exhibitions that are disembodied? While I sympathise with the semantics of such questions, I wonder at these critics. Have we come to expect an art experience will be frictionless? Do we accept galleries as disciplinary institutions and respond by turning docile? Should we try to become sets of floating eyes? I think about collection shows I have seen before, exhibitions that are so desperate to remove the hand of the curator, to sterilise the space around a painting to imply it can be approached objectively, as if such a thing were possible. Wall texts are edited to a bland house style, bodies are funnelled along predetermined pathways. Visitors are not trusted, are told this place is for them while they are held at arm’s length, denied autonomy.

The show needs to be hung like a game of Tetris to fit so much in!

The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong requires an active viewer. You need to be alert, to not bump into things, to interpret the hefty guidebook – there are no wall labels here – to locate yourself in relation to a number, to follow that number to a story, to make your own connections. It’s an empowering show. Buchanan explains that the title may even be read as an offer to consider your body – where you put it or who puts it where. But it’s only empowering insofar as it allows – and even creates – friction. Which it does through creating and sticking with a visual system even when it doesn’t always work (especially because it doesn’t always work!); through asking gnarly questions; through attempting to answer them with a show that feels both exuberant and uncomfortable, giving us enough pleasure that we are willing to stick with that discomfort long enough to be surprised and confused and pissed off and delighted. I still don’t know where my body belongs, in the gallery or in the world, but perhaps it isn’t about knowing so much as being immersed in it, and wondering.

i Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspectives,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599.

Ruth Buchanan: The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

7 December 2019 — 22 March 2020

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Photographs by Sam Hartnett