The Father Land: States of Becoming in the Writings of Martin Edmond

Simon Comber on the blurred line between fiction and non-fiction, and on discovering and journeying and becoming in the work of Martin Edmond.

I – The Haze

Every Tuesday afternoon my father catches the bus into the Auckland city centre. I’m working the late shift at the library and he comes in to meet me for my 4 p.m. dinner break. My father is retired and has a Super Gold card so he gets to ride the bus for free. We walk along High Street, sometimes pretending to look for somewhere new, always ending up at The Don for some Japanese cuisine. We spend the next forty-five minutes catching each other up on the previous week. No longer mind you. The bus isn’t free for seniors after 5 p.m.

At one of our recent catch-ups, I put something to my father I couldn’t have imagined putting to him a decade, or even a year, ago. Let me explain. He’s the only brother left. There were three but now there’s one. Cancer. Both. Lately I sense this weighing on him a little and it weighs on me a little too. It makes me feel like a good son to share the load and so I let it. I let it weigh.

– He tells me he’s watching me like a bloody hawk Dad says of our family G.P.

– I’m the only one left! he exclaims, wide and glassy eyed.

– I’ve gone right through my cousins and it got a lot of them, you know!

For me our weekly catch-ups were becoming inflected with an unfamiliar poignancy. I say unfamiliar because it had given me pause for reflections I couldn’t remember having had before. Not in this way. Not about my father. Yet in another way it felt like home. I would often find myself drifting off and away into a sentimental haze, replete with glassy eyes of my own, whilst Dad recounted the progress he’d made on the subdivision that was enabling my parents to retire, or the latest news from the cousins up north, the children of his eldest brother. It feels good to know you will miss someone when they’re gone, but every so often I was catching myself feeling like I missed Dad right then and there. This haze was the imagined inevitable future, and I was letting it colour the simplest of moments in the here and now. The haze was getting in the way.

So one Tuesday afternoon I asked Dad if I could interview him about his life and record the conversation. Once I’d done this I would be able to relax. Be more present during our weekly catch-ups. Safe in the knowledge that I’d preserved the kind of stories that so often seemed to vanish forever without warning. The ones we never think to ask until there’s no one there to ask.

But I didn’t want to make this about me – to weave myself in. It’s just that I didn’t know how else to get around to saying that I got the idea to do so from Martin Edmond. His first book of prose, The Autobiography of My Father, now twenty-two years old and still as difficult to classify as it is bravely poignant, this book had made interviewing ones father seem like a good thing to do.

I think this is why I made the tapes – to steal something back from death.

II – Memory, Voice, Occasion

Ohakune-born, Sydney-based, 62-year-old Martin Edmond has been a prize-winning poet and a prize-winning screenplay writer in his time. These days he is a little dismissive of his abilities in both realms. And well he might be. It’s not simply a matter of antipodean self-deprecation, though I do sense a touch of that. It’s also the fact that there is something else he does better, even if he’s not particularly fond of the umbrella term currently used to describe just what that is.

I made my first in-person impression of Edmond at the 2012 Readers and Writers Festival in Auckland. I’d not yet read The Autobiography of My Father, nor any of the major works that followed. I’d only read Ghost Who Writes, Edmond’s contribution to the Montana Estates Essay series. Ghost Who Writes explored writers like Fernando Pessoa, Walter Benjamin, W.G Sebald, and a poet I had a lot of time for – Charles Baudelaire. It focused on the self-negation, deflection, multiplicity and resulting ambiguities that complicated their writing voices. These voices were complex and disavowed certain distinctions normally drawn between story and fact – between the life and the art. Any pure line between the artist and the art was always an illusion of course, but these writers made you stop and think about the implications of this, and maybe even apply them to the transaction between yourself and the books you read.

Baudelaire can be seen as a forefather of these voices. His influential definition of the modern, which his writings on art and culture had so astutely articulated in the latter half of the nineteenth century, had emphasized the fleeting, the transient, the contingent. The authors that came in his wakecan be viewedas arising from a hyperawareness of these things. What simmers unwritten in Baudelaire’s essay The Painter of Modern Life is that it is not merely fashion and the arts that are always fleeting. The artist is fleeting too. These voices seemed to acknowledge this unshakable fact on the one hand, whilst trying to dodge it on the other. If you negated or contorted your own “I”, if you dissolved the boundaries between history and imagination, between life and art - if you got in first: then maybe time wouldn’t have a chance to take its crazy toll. Maybe your voice would be preserved.

Edmond was taking a ‘Creative Non-Fiction’ workshop during the festival. I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant, but I was interested in the multiple skills it might take to do creative justice, ethically and aesthetically, to a subject of historical or factual import, and whether those skills might be utilized (God forbid) in songwriting. I went along. I still remember his quietly confident, unassuming countenance; his notion that the word ‘perhaps’ could be useful and that speculation was a right; his contention that writing was an action to be engaged in rather than a vocational badge of honour; his belief, based on experience, that the best writing was usually that which surprised the writer and had not been preconceived; his use of the word ‘selective’ in tandem with the word ‘truth’. It was more of a drifting, freewheeling conversation than a workshop, but it was always compelling, and I think fondly back on the way he fielded every question with the same warmth and sincerity - no matter how little it had to do with what I thought of as the craft of writing.

– My grandfather just refuses to open up, confided one woman who was having difficulty completing her family memoir.

– What do I do? I mean, no matter what I say!

Edmond had smiled courteously.

– I’ve found that whiskey always helps.

What I found most interesting was Edmond’s outline of the myth of the three muses – memory, voice, and occasion - as recorded by Pausanias in the second century. Memory was the engine or the muscle – you were honouring memory when you sat down to write. Voice, or song, was a duo – the internal narrator and the internal listener. Occasion was the act of writing - the present tense in which this act, engaging a ghostly reader, occurred.

Perhaps one thing those in attendance were not expecting to hear was Edmond’s distinct lack of enthusiasm for the very term after which the workshop had been named: ‘creative non-fiction’. A writer aware that there was no Spanish term for ‘non-fiction’ was, I suppose, unlikely to be satisfied with a genre term which seemed to be hedging its bets more than pinning down a style– to say nothing of the preposterous implication that any non-fiction not labelled as such was devoid of creativity. Ghost Who Writes can be read as an acknowledgement of some of the writers who have influenced him as much as an illumination of them. Since 1992 when The Autobiography of My Father was published, Edmond’s own body of work has grown to include six major prose works, three shorter works, and four essay collections. He has done as much as any writer to complicate those traditional distinctions between fiction and its presumed counterpart.

III – States of Becoming

History can be ruthless to artists who try their hand in multiple mediums. After all, that’s as good a way as any for one to avoid an all-encompassing sense of commercial or artistic failure - spread it around. Hence that most stinging of artistic insults: dilettante. Less common is the story of an artist striving in one medium who eventually makes their best work in another.

You will not find in the early poems of Leonard Cohen many examples of that sublime synthesis of form and content that he achieved with songs like Suzanne or Hallelujah, but you will find he was often writing in simple rhyming couplets, a metre that had more in common with sixties folk songs than anything that was happening in contemporary poetry at the time. In hindsight the transition seemed natural, and despite Cohen’s own canny explanation, not just because there was more money to be made on the stage than the page. When David Simon was writing for The Baltimore Sun in the eighties no one could have foreseen he was developing the kind of critical thinking and universal empathy that would help forge one of the most kaleidoscopic, compassionate television dramas ever produced. Ernest Hemingway once decreed that Newspaper work will not harm a young writer and could help him if he gets out of it in time. He could have been talking about David Simon and The Wire, but who knew?

Martin Edmond is another case in point. Before he’d written any of the books of prose for which he was awarded the 2013 Prime Minister Award for Non Fiction, and more recently, a New Zealand Society of Authors award, Edmond was striving to write great poems. He was also writing about art. And that’s when he wasn’t on the road with Red Mole, an experimental theatre troupe founded in the mid seventies by Alan Brunton and his partner Sally Rodwell, for which Edmond had deserted a potential career as a University lecturer.

In a review of Philip Clairmont’s New Auckland Paintings exhibition, from the Winter 1978 edition of Art New Zealand, I sensed facets of Edmond’s burgeoning, prismatic voice. His employment of poetic devices to articulate what he sees in front of him, whether on a canvas or in his minds eye; his tender precision when doing so; his appreciation of a certain paradoxical quality that seems to run through life and art;his willingness to suggest philosophical implications immanent in the work. Considering the principal recurring motif of light bulbs running through the paintings, his mode of explication is more poetic than technical.

Yellow light from a bare bulb twisting on its iron stem reveals an unimaginable splendour in the midnight room. A tongue of flame is the characteristic shape: all of these interiors move as shadows move in a firelit room, or in a room where the bulb is swinging on its cord.

He observes the way these omnipresent flaring bulbs transfigure their surroundings, and he touches on that contradictory sense of oneness between art and life which Baudelaire had declaimed in 1864: La dualité de l’art est une conséquence fatale de la dualité de l’homme. -The duality of art is an inevitable consequence of the duality of man.

It is as if the yellow light has energized the interior, has let the ordinary objects in motion so they grow towards the light as the light grants them brilliant colour. Clairmont’s realism remains paradoxical. His painting of household subjects is a kind of realism, because it is always possible to recognize what he has painted. At the same time the vision is subversive of realism. You recognize an object only to lose it again in the phantasmagoria.

Noting that the power of these bulbs seems to match the intensity of the sun, he allows himself a somewhat Beckettsian philosophical reflection.

The Source of energy is ultimately shared and I guess it all came from the same place in the beginning, just as it will all leak away down the same sink in the end.

IV – Loss of a Halo

In 1980, Edmond’s Streets of Music was awarded the Jessie Mackay prize for best first book of New Zealand poetry. What is perhaps surprising is that you won’t find within it any writing more potently focused, or even more assuredly poetic, than what was already being displayed in his art writing. The centrepiece is the intensely elegiac Fool’s Gold. Within it you will find an eye for a graceful mortal simile.

The days blow by like leaves in the book of the dead

You will find an understated philosophical refrain that in its haiku-like simplicity feels inflected with the wisdom literature of the Orient.

At the end of the day I always feel a wiser man

When morning comes I have to start all over

There are lines of dark, visionary intensity and accumulative power.

The window opposite my window turns

my shape to a dragon of smoke and writhes

as the Fool steps out once more across all creation

head in the clouds feet stumbling at the abyss

multiplying zero in the round of the boneyard moon

And as often occurs in a more fleshed out manner in his prose, references to popular culture walk hand in hand with strange, anomalous contemporary human happenings and classical history. In this case, a lyric fragment from the most rhapsodic song on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks is juxtaposed with the Jonestown mass suicide of 1978 and a metaphor plucked from the annals of ancient Egypt. There is an incantatory repetition that brings to mind Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and America.

914 bodies lie out in the Guyanese jungle today

914 bodies all misty and wet with rain

914 bodies of the faithful looking for paradise

914 bodies as a visible sign

like Tutankhamen in his golden casket

But it’s hard to ignore those other aspects of the poem which feel at odds with the central quality of the prose he would come to write. The very title Fools Gold implies a disillusion with humanities tendency to quest for the superficial – for riches. Even if there is that pot at the end of the rainbow, the reasons you seek it will be your downfall.

Then there’s the focus on America, which fails to ring true. Ginsberg had noted that America’s libraries were full of tears in 1956. Did the world really need a New Zealand poet in 1980 imploring America, as Edmond does in the opening line of the opening poem, Simple Maze, to Cry your heart out? As a poet, prize or no prize, Edmond didn’t seem to know which way to turn. If his somewhat haphazard line breaks didn’t tell you that, it was there for the reading:

and everybody has to go to another place

but there is no longer anywhere else to go

and everybody has to go to another place now

and there is no longer anywhere else to go

On the other hand, the prose to follow would never stray for long from Australasia, and, more often than not, no matter how widely it roamed the rest of the world, would return to Edmond’s hometown of Ohakune. It would feel all the more vital for it.And whilst his future work would not be arguing in defence of the quest for riches, it would be daring to seek alternative quests. The central redemptive message that emerged as I read through his major works was that it didn’t matter whether you were flying between countries, wandering on foot, or seated at your writing desk, deep within your imagination, artfully linking up the chains of memory: there was nowhere that you could not go.

In Ghost Who Writes, Edmond makes reference to one of Baudelaire’s prose poems, Perte D’Aureole (Loss of a Halo). The halo is the demarcation of the great poet, and the character in Perte D’Aureole is only too happy to be done with it. De-haloed, incognito, a mere mortal, one is free. Edmond had felt an intolerable weariness at the sound of his poetic voice, and a similar sense of liberation when he finally stopped reaching for that halo. Forsaking the formal concerns of metre and line break, Edmond found himself able to write with the whole depth and breadth of his interests. That’s one way to frame what in hindsight was an important literary transition for an important New Zealand writer. But I have heard him tell it another way. At the workshop he didn’t give himself all the credit for finding his own voice. The way he told it that day, it was the voice that found him. Edmond had struggled to write a speech for his father’s funeral, but he nevertheless got up to speak. The voice in which he gave the speech seemed to well up effortlessly, as if finally unlocked by his fathers passing, and it was this voice in which he began to write. And there is another side to this story.

V - Day for a Daughter

In late March of 2014 Martin Edmond came to Auckland for the launching of Beyond the Ohlala Mountains, a posthumously released selection of the poems of his old Red Mole compadre Alan Brunton. Edmond had edited the publication alongside Auckland-based poet Michele Leggott. It was Leggott who had aided the publication of Edmond’s first manuscript of prose by forwarding it on to Auckland University Press over two decades earlier. A Red Mole-esque opening dance scene culminated in Alan’s daughter Ruby lifting the new book out of a briefcase, holding it aloft like some long lost antipodean talisman. Then Edmond and Leggott walked ontstage arm in arm (because Leggott, who suffers from a degenerative eye disorder, is now legally blind) to briefly introduce the book. I was struck by his recall of events, but also, given how much he has written and how longstanding his acquaintance with Brunton was, by how little he said. After recalling the year and the publication in which he first encountered a particular Brunton poem, he simply added that

– Alan’s poetic voice has stayed with me ever since, and editing this selection has been a dream project.

He left it at that, and for most of the rest of the night watched the proceedings from a far back corner of the Marae. When I spoke briefly to him that night I told him how moved I’d been by Ruby’s reading of an excerpt from her father’s long poem Day for a Daughter, and how impressed I’d been by Peter Simpson’s reading, delivered forcefully in his deeply resonant and weathered voice, replete with jazz-inflected, improvised piano accompaniment.

– You know he ran for Parliament? Edmond replied instantly.

I confessed that I did not.

– Oh yes. He was a Labour M.P.

There was something about the tone in which he said this to me, calmly yet insistently, that seemed to reveal one of the engines that drove his writing. How could I fully appreciate Simpson’s bold, impassioned delivery without some small extra shard of historical backstory? Did the fact of his erstwhile political career not further illuminate his fearless public performance, which I had heretofore only known to attribute to his background as a university lecturer? The more of Edmond’s books I read the more I was struck by how often, and how easily, he would reach into the past to illuminate the present, or vice-versa. Some new connection between people, places, history or inanimate objects; or some fresh context for what already seemed set in its apposite context; or some re-gathering of any number of these strands, was only ever a few pages away. If there’s one word that Edmond could be accused of overusing it was the word inchoate. I’d been encountering it over and over, and yet I’d never tired of it. Perhaps I derived from it, like the author seems to, some form of relief from that mortal knowledge that makes us human: a welcome reminder in a world of endless inevitable endings that the universe is in a continual state of becoming. Bob Dylan, a songwriter Edmond has alluded to in the past, had once said that if an artist could stay in this state they would sort of be alright.

A few days after the launch I went along to the Audio Foundation where Ruby Brunton was hosting a book sale of various volumes written by her father, and just as alluringly, books her father had collected throughout his life. As I browsed the books I found myself recalling something Edmond had written in a moving piece for Alan Brunton, an elegy entitled . . . among the ruins with the poor.

He said some hard things to me over the years, including the intimation, in two cryptic remarks made seven years apart, that I was a prose writer and not a poet; but there was never any malice in it, only the hope that what he said would be taken as what he meant . . .

Paperbacks were just five dollars a pop so I got a bunch, including Day for a Daughter. After Ruby had totalled up my books I asked her about those intimations her father had made.

– A few years ago I visited Martin in Sydney, and he told me how glad he was that my father had told him that, Ruby said, her voice somehow matter of fact and full of daughterly pride in equal measure.

Not that Brunton was encouraging his friend to forsake the poetic altogether. As Baudelaire had once written, Sois toujours poéte, même en prose – Always be a poet, even in prose. The first fruits of this new voice, with its confounding, Borgesian, and perfectly apt title, was The Autobiography of My Father.

VI - Listening To The Wind

Edmond’s first major work of prose begins in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales. The narrator and his female companion are tramping to the Jenolan Caves – a world-renowned formation. Though both sites are popular tourist destinations the lack of tourists is conspicuous. And given the cow shit, so is the lack of cows. In fact there are no other living souls, and perhaps that is one reason why this opening feels from the start like an allegorical journey into some kind of interior. The external world is portrayed as an oppressive force. The heat is percussive, the water is undrinkable, and the dung flies raid the corners of your mouth and eyes for moisture. Their climb to the top of a summit is as cruel as life. We follow the writer and his companion for two days through valleys and rolling country, up hills and dales, into fickle south-westerlies, and alongside rivers and creeks. On the second night, camped out in a clearing, the narrator thinks he hears a kangaroo, and is only scared because he thinks it might be a human. And then, finally, inside the tent, it is quiet enough, and we are far enough into the interior, that the author’s consciousness, that merging of memory and the human heart, is able to emerge.

But sleep did not come. All of this is just a preamble. And I’m sorry to have gone on at such length with the details of the journey, but it was the only way I knew how to get to the point. The point of me lying awake all night in the middle of nowhere, listening to the wind and thinking of you.

As is so often the case in Edmond’s prose, there is much journeying. Having recalled his own sudden wave of exhaustion, and calculating that it must have coincided with his father’s life-ending stroke, we follow the author across the seas from Sydney to Auckland, down to Wellington, across to Miramar, and finally over the Rimutakas to Greytown for the funeral. Family reflections, close-ups of old photographs, momentary digressions into genealogical speculation, reminiscences on the ups and downs of his father’s emotional life, hard questions and half answers - these things are interwoven with funeral preparations, speeches, and those flashes of recognition that come out of nowhere when one is in the midst of a mourning multitude.

We pass through passages of tender, understated prose, and passages that are so unpolished as to feel more like routine diary entries than the carefully revised pages of a published manuscript. This alternating between the gently artful and the seemingly artless is overlayed by a further back and forth, between the first person ‘I’ of diary-like family proceedings, and the second person ‘You’ of deeper reflections. Perhaps some of the power of these pages comes from the fact that this second person ‘You’, traditionally used to address the reader, is in this case used to address the deceased. Which is not to say that Edmond was necessarily cognizant of a difference between the two as he wrote. We are slowly released from these strands of narrative mode, and these layers of memoriam, back to the caves where we started. But we are deeper and darker. A two-page piece entitled Underground rises to meet the reader.

Far down in those dark passages, the dead whisper on a cool dry wind that blows endlessly through the caverns. It is their buried lives they talk about, in words no one now can understand. All that could not be told, all there was not time to say, all that inchoate frenzy of thought, lingers there and is not forgotten.

And when that second person ‘You’ returns it no longer seems addressed exclusively to Edmond’s father. In its shift from past to present tense, it becomes a startling, poetic farewell to everyone living who will one day die.

On the cool dry wind that blows where it lists, with all its freight of weightless voices, you travel endlessly until, in some unknown vortex beyond comprehension, you suddenly see lights above you. Many lights, pricked red-gold, or silver, or blue into the velvet of the night.

And then you disappear forever into the black spaces between the stars.

The rest of the book, now forever in the shadow of Underground each time I return to it, is something of a collage: the taped interview between the writer and his father in which The Depression and WWII make their presence felt; a poem penned by the father in memoriam of a friend killed in the war; a characteristically detailed, Edmond-esque description of his father’s final Greytown abode where the interview was conducted; a drive back to the family hometown of Ohakune; and, most uncomfortably, a transcript of the notes the father made when he was in a psychiatric ward. It is both painful and poignant to read Trevor Edmond holding his own past to account with the help of Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving, ultimately using it as one more way to measure his failings rather than a key to inner peace. His notes only seem to become more fragmentary and despondent.

I feel the need of help but suspect I am beyond help at this stage. I have a sense of unreality about the world and cannot seem to come to grips with it. I wonder sometimes if I am two people and I do not know which is the real one at all.

The duality of art. The duality of humankind. The inevitable.

VII – I’m Nothing

I was rostered on in the library basement for the hour before my dinner break. I was also stressed out about this article. For starters, I was torn. From the get go I’d personalised it. I’d figured that if an artist’s work had weaved its way into your consciousness, then it was only right and proper to weave yourself into any response you might have to give. But I was insecure. Part of me wanted to erase all trace of myself. And then there was the fact there was so much to read, so much I wanted to cover, and I didn’t know where to draw the line. It had begun to envelop me. I’d decided to focus on Edmond’s first and last major works to date in the hope these bookends of his career would encapsulate some of what made his voice worth preserving. But how could I leave out the impassioned, unflinching artist biography The Resurrection of Philip Clairmont; or the reflections on Rimbaud and Van Gogh, and the tumultuous recollections of life on the road with Red Mole, that ran through my personal favourite Chronicle of the Unsung; or the scholarly yet fantastical summation of European journeys in search of Australia that made up Luca Antara; or those equally worthy shorter pieces collected in Waimarino County and Other Excursions?

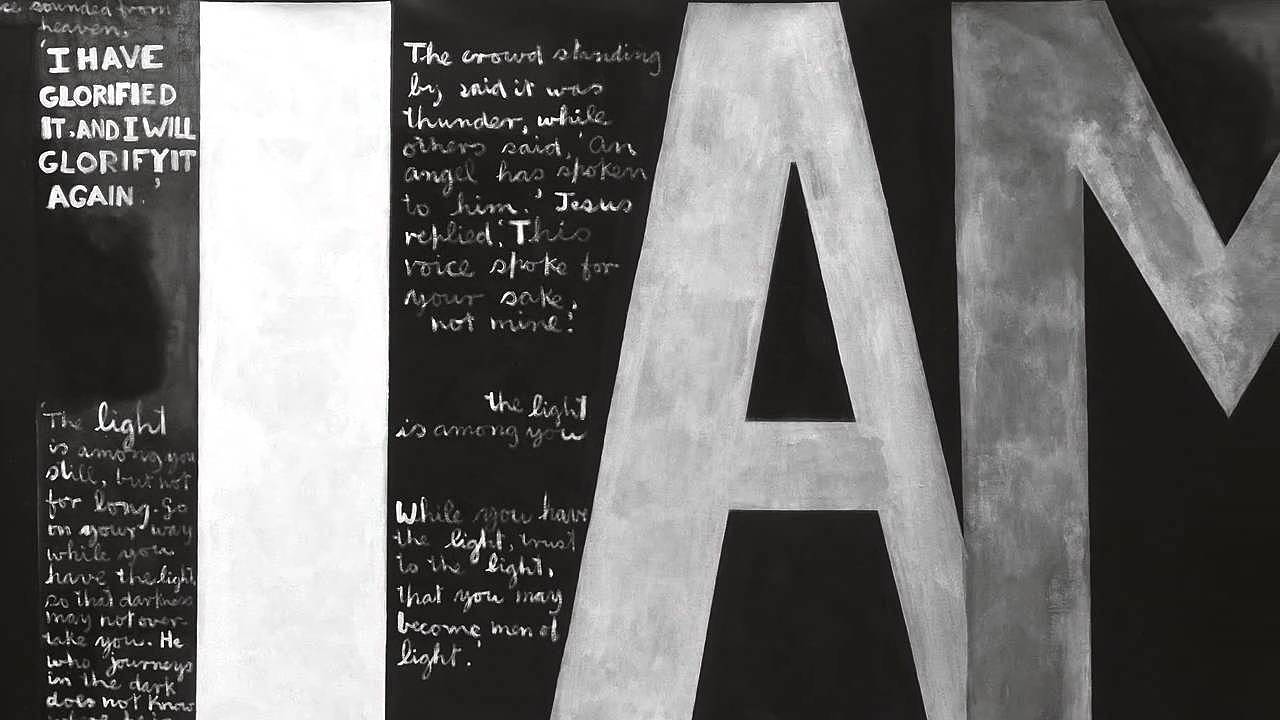

Either way I had more to do, and so gambling on the fact management rarely descended to that dust-ridden sepulchre of books actually worth borrowing, I ignored my roster, went up to the Auckland Research Centre, and kept on with my reading of Edmond’s most recent work, Dark Night – walking with McCahon. On a second reading it had struck me that if one was looking for a supreme New Zealand equivalent to those post-Baudelarian writers and their unstable ‘I’, it would surely be the painter Colin McCahon that came to mind before any writers. The books epigraph, a quote from the painter himself, spoken when asked by someone if he was a catholic, exemplified this.

I’m nothing . . .

His paintings exemplify this too. Immerse yourself in his work and those ‘T’-shaped tau crosses, so omniscient in certain periods of his career, start to resemble the ‘I’; and, in turn, the recurring ‘I’ begins to echo the cross. This bleeding together of symbols seems to imply that the self is a load to bear - the self is a cross. And as Edmond suggests in Dark Night, if ‘I’ is nothing, does that not also imply that ‘I’ is everything, like the very air we breathe, invisible but always there? Maybe this was why he’d chosen a McCahon painting called Cross to appear on the cover of The Autobiography of My Father all those years ago. The cross, like family, is everything.

At some point I’d looked up from Dark Night to notice that my father had seated himself only a few desks away from me. He was half an hour early for our weekly catch-up, and he had an old brown box of journals on the desk with him. This was not usual. I’d never known him to be any kind of researcher. Suddenly overcome with some vague sense of leftover teenage guilt, as if in danger of being busted by my very own father skiving off on the job, I got up and left. But what was he up to?

VIII – The Spirit Path

Edmond had already written about McCahon back in his art reviewing days. In a 1976 copy of Spleen, a lively, opinionated arts and culture rag founded by Alan Brunton and Ian Wedde (and named after Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen prose poems), Edmond reviewed McCahon’s Scared paintings. McCahon had perceived parallels between the Christian allegory of the Fourteen Stations of the Cross and the Maori legend of the spirit path, both of which are made manifest in the painting Te Tangi o te Pipiwharauroa - The Flight of the Shining Cuckoo. For Edmond, travelling visually across the panels of a McCahon painting became a rehearsal for the journey of the Fourteen Stations or the Maori spirit path. The worshipper is to follow the process through from beginning to end & to live it as he moves.

Dark Night begins with something of a preamble just as The Autobiography does: in this casea childhood recollection that illuminates Edmond’s longstanding, deep-seated connection to McCahon, and to art in general. From a distance of half a century, and all those miles that separate Sydney from Ohakune, he recalls the McCahon painting for children that hung in his room as a child - Landscape with Trains, Boats and Cars. He declares it to be the one that claimed me first.

. . . it is so heartbreakingly familiar that I do not quite know how to begin to describe it nor truly to understand why such a description should be necessary; for it seems to be one of these things of the world, like rain or light, that are elemental.

But describe it he does, considering each image and its implications over a number of pages. I think of one of Edmond’s literary touchstones Walter Benjamin. In Susan Sontag’s essay Under the Sign of Saturn, she conjectures that Benjamin could write about himself more directly when he started from memories, not contemporary experiences; when he writes about himself as a child.

And from the early 1950’s in Ohakune we travel forward into a later past - Sydney, 1984. McCahon had flown over with his wife to attend a retrospective exhibition of his work. On the afternoon before the opening he had disappeared whilst walking through the Botanical Gardens. Police found him 28 hours later in Centennial Park. Without identification, and unable to say who he was or where he’d been, he was taken to St Vincents hospital and then transferred to a psychiatric centre. Edmond sets himself the task of imaginatively retracing the journey McCahon might have made through those unaccounted for hours, contriving his very own psychogeographical spirit path through the city. In doing so he enables himself to make good on that statement of intent from 1976. This book lives and breathes its process. It follows through.

Edmond uses that evocative word, psychogeography, as the title of the second chapter. It had originally been defined, if not invented, in 1955 by Guy Debord, founder of the Situationist International movement. Debord, a Marxist intellectual with an anti-bourgeois, revolutionary agenda, described psychogeography as the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. Debord and his cohorts would pre-conceive a drifting journey, or dérive, through Paris, sometimes by trying to follow the map of a different city. The dérive was a technique of transient passage through varied ambiance. It’s not surprising that Edmond, a writer so fond of paradox, was drawn to the somewhat contradictory notion of trying to pre-conceive an accidental journey, even if his motivations were literary instead of political. Rather than walking through Sydney following a different map, he utilizes the allegory of the Fourteen Stations of the Cross, choosing various geographical landmarks through Sydney to stand in place of the stations. Lest this sound a little too highfalutin, you may want to consider his first Station is the public toilet in the Botanical Gardens, the last place McCahon was seen entering before he disappeared.

The reader follows the writer following the ghost of the painter through the Sydney environs - the sights and sounds, the man-made and the natural, people and animals, the living and the departed, the contemporary and the historical. Everything is backlit by Edmond’s irrepressible curiosity, his fugitive empathy, and the memories, both bitter and sweet, of the author’s own past- his familiars.

Entering those same fateful public toilets brings to mind watching the All Blacks with his father and those ritual half-time visits to the ablutions. A local pub gives Edmond pause for thought on the problematic credit given to intoxication in the making of certain works of art, and then further thoughts on the alcoholism that runs through his own family tree. An absence of transvestites on their usual block becomes a palimpsest, written over by memories of the legendary New Zealand drag queen Carmen, and her cabaret venue in Wellington, Carmen’s Balcony, where Red Mole gave many a performance. Edmond anoints Carmen as the Veronica of the sixth station, wiping the face of McCahon-Christ as he carries the cross of art towards his destiny.

After the Fourteen Stations the author still has one last self-set task: to live the namesake of the book, and that of the sixteenth century poem by Saint John of the Cross that is its source – to sit through a Dark Night of the Soul in Centennial Park. As he waits it out under the stars, that dense forest of details and labyrinthine connections he has traced throughout the book finally thins out. Edmond has a vision. The light suddenly appears silver, and seemingly sourceless.

I looked at my hand and it glowed with the same calm radiance. I walked a little way out into the open and stood, turning slowly full circle while watching the round of trees that ring the ground, turning too. Their tops were feathery and dark against the silver sky and they were pulsing, opening and closing the way anemones will in a sea pool. It was quieter now than it had been, quiet as it ever would be: in the dead of night everything was alive. Out on that hallowed ground I felt my own consciousness go . . .

And so perhaps it is not utter negation of the ‘I’ that the cross of art journeys towards, but simply assimilation of the ‘I’. A lightening. A diffusion. And maybe that’s why the book does not draw to a close after the fourteenth station. There was no endpoint Edmond could arrive at. There was always another stone to be upturned. The quests he sets off on lead not to answers, but to more quests. I sense not only lamentation, but also an excitement that we should be grateful for, when he writes:

We all take secrets with us to the grave and the most profound of those secrets is who we really are. Those left behind may turn over clues, they may make suppositions, they may in their speculations approach as close to the truth as we are able to go; but we will never really know.

IX – The Drift

My grandmother had taken a secret to her grave too. No one seemed to know anything about her father. Only that he’d not been the best father you could wish for, and that he’d disappeared at some point. But the whys and the wherefores were things she’d refused to divulge right till the end. When my father had asked her about it one last time, a few days before she entered hospice, he’d been met with a stern silence. He only had one lead. He knew part of her early childhood had been spent in Motatau, about an hour north-east of Dargaville, where Dad had spent his own childhood. It turned out that when I’d caught sight of Dad in the Auckland Research Centre he’d been looking at Motatau school yearbooks. He’d also been doing Ancestry.com searches. As he explained to me during my dinner break that evening, he’d taken up a quest of his own. Over a decade after Grandma’s passing, my father had finally started trying to fill in the gaps, and he was making progress. For starters, he now knew where my great-grandfather was living when he’d passed away - a psychiatric ward in Sydney.

– Rydalmere Mental Hospital! 1960! My Lord! The things you can find out on the internet nowadays! Can you believe it? he asked me, shaking his head.

I believed it. Some new connection was always just around the corner. Nothing was strange anymore. And whilst Dad moved on to talking about the latest developments on the subdivision, I drifted off and away again, far from my father’s voice. Not into that melancholy haze that had on occasion held me frozen - thoughtless, speechless, a ball of pure emotion. I drifted somewhere else, where tangible, recognisable thoughts were able to arise. These new family revelations; my father’s pleasure in seeking them out and reporting back; everything I’d been reading over the last few months - these things hovered, crystalline, and slowly coalesced. In that moment it suddenly seemed to me that stories didn’t vanish. They merely unwound. As those who held together certain strands of what constituted those stories passed on. It was the job of the living to re-gather the strands – however they could and however they saw fit. To spin the old story anew. Either my thoughts let go of me or the tone of my father’s voice changed, stealing my attention back.

– It’s not for the faint-hearted is it, he said.

– No, it sure isn’t, I replied, having no idea what he was talking about. All that goes in to planning for ones retirement, or just life itself?

I still wanted to do the interview, but no longer for me - for my father. And I knew what I would ask him first. It would be that same first question that Martin Edmond had asked his own father, recorded on to a tape reel, and then transcribed into his first book of prose. A question that seemed straight forward enough when I first read it.

What is the earliest thing that you remember?

It was so much more than a question. It was a reminder that there was always another side to every story. It was an admission of liability. An acknowledgment of loss. A trap laid for a ghost. An invitation to dream.

And if there is an illumination to be had amidst the perplexity, this may be what it is: I’m not possessed by a god or goddess or any other alien or familiar spirit, I’m not speaking in the precinct of the temple, I’m not intoxicated or deranged, my words are not prophetic or otherwise revelatory of the sacred; and yet, mysteriously, even here, even now, in this most prosaic of circumstances, a man sitting at a computer in a small flat in a modern city, the ancient conditions of vatic speech continue to manifest: memory, voice, occasion.