The Canary In The House Party

There's plenty up in the air with music writing right now, though music writers are understandably more worried than the rest of us. But toasting the end of their paid gigs in a blaze of technology and commerce might end up being cold comfort.

During my first year or so at university, I held two things to be certain. One of them was my job as a checkout operator and supervisor at Foodtown; the other was the steady trickle of album reviews, news roundups and artist interviews I would do for places like Real Groove, Craccum, and a couple of other stop-start publications that no longer exist. I knew I liked listening to music, arguing about music, and getting drunk and going out to see bands, and working twenty hours a week meant I could afford to do it.

By comparison, university was this nebulous cluster of hours where I travelled into town from the suburbs and wandered around in a daze – sometimes I was okay at it, but I hadn’t pieced together why I was doing it yet. I missed a lot of lectures because I stayed up too late for other deadlines. And why not? I was even getting paid to write, sometimes as much as 20 cents a word! I was very nearly living the dream.

A lot has changed nearly a decade later. The things I marked my days by are virtually obsolete. I recently went on a bit of a tear about how Spotify and Pandora was to music writers what the swelling and indifferent banks of self-service kiosks were to supermarket workers. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. In each case, sophisticated computer technology allows people to complete a basic service themselves. One is scanning and paying for grocery items. The other is discovering and being guided towards pop music they might be interested in (an original structuralist basis for music reviews that music writers themselves have often lost sight of – there’s a reason why Robert Christgau’s review column was called the Consumer Guide for 40 years).

The sophisticated computer technology means you need fewer and fewer humans to do the stuff. Like self-serve checkouts, some people still prefer the personal touch and go out of their way to the remaining sources of it. This might be one of the few remaining ‘record store guys’, or a Simon Sweetman figure. There is probably a generational preference to this pattern of behavior. And like self-serve checkouts, you get weird new irritations that are never enough to completely put you off. A music streaming service directing you to James Blake, who you hate, because you listened to something moody and electronic and modern before and the machine just didn’t get the nuances, is the cultural equivalent of being instructed to place your last item in the bagging area. But both appear to be the way forward (ie: they’re not fads).

The difference being – having tried my hand at both, I feel sorry for checkout operators, who are predominantly female, middle-aged, often migrants, and often have low levels of education to perform physically demanding work (you try standing up eight hours as a grown-ass adult). And I don’t at all for music journalists, who have historically been statistically the opposite, generally had a better handle on their opportunities and choices and got to spend lots of time doing a fun thing they liked. But my own complexes aside, there’s some thorny issues in this and I think we should care about what happens to jobs like these – part-time or casual though they were and are.

Writing about music in an interesting and challenging manner’s not necessarily going anywhere, but the paid gigs have a fraught relationship with commerce that’s creeping into other culture writing and from there into journalism. And what happens as obsolescence creeps into more and more of these dead-cert middle-class roles? First, they came for the people who write local gig reviews and I said nothing. Then they came for me.

*

Important: you can still get money to write about popular culture! One of which you like getting, and the other one you like doing. You also don’t have to do both, and this is fine. But you might find if you’re writing concise and original pieces about rap or dance music and technology and intersectionality that read like Tumblr-on-the-Ritz (focused, mean, great) you might be getting paid a little less. And if you’re using a lot of Game of Thrones GIFs and a listicle structure as mortar for someone’s bricks of advertising, then you might be getting a little more. It sounds disgusting because it is, but there are more serious things to compromise still.

It’s not just an Internet thing. Everyone, me included, laughed long and hard at this text, allegedly from a oft-mocked New Zealand music publication/gaping maw for revenue. But, I mean, it’s still the equivalent of laughing at Russia for a messy and corrupt Olympics – ie: a more brazen and unfiltered version of the same shit everyone else does low-key. Because I also had reviews held back by editors because they were ripping the artist on the cover page a new one, and I also felt the pressure to write treacly three-starrish reviews or cosy interviews of artists that were being pushed by decent people in record companies who were worried about their jobs. Everyone worries about their jobs, even the scrappy ones. You have a lot of fun, then you hit the limits of what you get away with. Print publications and trad record companies saw out the last decade clinging to the same raft and the result had to be a lot of playing it safe.

This doesn’t mean there’s not money floating around (or people making it). Contra some of the more socialist techno-utopian predictions around What The Internet Would Mean™ (the end of markets, or at least their democratization), it hasn’t actually killed off telecom and media conglomerates. It’s been co-opted. The same people are sitting at the top in new and bigger consolidations of wealth – the baton is not handed over from generation to generation, so much as merged into one giant platinum baton. They invest in private healthcare, electronic security services, resource extraction and better online portals for WalMart. They are also very eager to invest in young enthusiasm.

This all got a rigorous airing in Chris Ott (Shallow Rewards)’s vlog at the start of December: He points out that these aren’t little publishing endeavors, like the attics Rip It Up or Real Groove ran out of, but the products of venture capital – the cool loss-leader in the portfolio that makes investors sit up and take notice. Cool needs fuel. Exuberance and personal investment, and preferably something that no one else has gotten to yet. Writers are the A&R reps, music is the advertising silo. This is new and treacherous terrain as either a fan of artists or as a writer.

He singles out Liz Pelly for her breathless piece on Massachusetts’ DIY scene for the NME(a TimeWarner Inc publication). Honestly, I don’t think she should be attacked as some glaring example for what everyone’s doing – whether they’re writing for Complex Media for Pitchfork, for Stereogum. Though I can absolutely understand the thrill and mythology of drawing the dots from a local scene to the NME, to Spin, to VICE. I get this. That shit runs generations deep, and even if you’re savvy enough to know how the business models work, that still clouds your judgment.

The tension in Pelly’s NME writing, or on the 285 Kent eulogies or on others, on is that you basically have these wonderful bits of writing on having fun and being young, but what’s exciting about them (including the bad times) as been sanitised and burnished to act as a PR advance, a best foot forward for the scene as packaged lifestyle. I think about some of the happiest times of my life when I was 20 and seeing Teen Wolf, The Whipping Cats, Disasteradio and The Vacants play house parties in Kingsland and Sandringham and Arch Hill. Even then, I would have felt weirded out by a whole bunch of press around those guys, by 28-year-olds with craft beers and good shoes muscling in to check out a fun little band because a major outlet called it the next big thing. And now that I’m that older dude, I want to accord the 20-year-olds playing house parties some fucking space.

If this is the way things are, the corrective isn’t that helpful. Too much polemical blowback that’s less about asserting a case for music in the here and now than it is on asserting a bygone time. Here’s Joe Steinhardt in Boston’s Fvck The Mediaon 2013, which is apparently the year punk and independent music DIED:

“2013 for me, will be the year that I saw major label corporate bullshit successfully marketed to independent music lovers like never before…If you run an independent music blog, if you are an independent artist asked to make a best of list, you shouldn’t be anywhere near artists that are up for a fucking Grammy this year, because (1) that’s embarrassing, (2), that’s doing a huge disservice to your readership, and (3), to put it bluntly: if you’re an independent artist or journalist writing on an independent music website no one cares what your opinion on pop and pop-rock is. No one cares what your favorite pop records are right now. Wanna listen to it? Fine, go ahead and enjoy it, but promoting it is embarrassing and unproductive. Imagine asking the owner of a local independent coffee shop for a recommendation on where to eat a vegan meal and them telling you Chipotle..All of this stuff is not just embarrassing, but it degrades what little importance is still left in the idea of being an independent artist. Independent of what? What is the point? “

A charitable account of this might be that this is a valuable counterpoint to the notion of ruthless pragmatism and making a living while you can, to the celebration of mainstream commercial culture in spaces that have traditionally liked to posture as being in opposition to that culture, to notions like ‘independent’ and ‘local’ as branding exercises and content. A less charitable account is that Joe Steinhardt is engaging in the music journalism equivalent of LARPing.

If these problems seem intractable, it’s because they sort of are. They're not just issues in terms of how we get our consumer guides either - see Elle's Hunt's piece for The Wireless about BuzzFeed's posturing as a Koch-funded source of news, and lament. I get worked up about this stuff – lots of people do, lots of people should no matter what side of the argument they fall – but more and more, I think we’re rushing to diagnose and cure a symptom. Not a cause. And now I mount a defence.

*

We don’t actually hate people who write for a living, or a part of their living, right? I certainly don’t, once I get some perspective. But we don’t attribute the same queasy nostalgia and sadness to the erosion of paid or meaningful written work that we do to the people who used to work in factories a decade ago (“Ahh, the dignity of labour! But also I want to buy things cheaper from China.”). Nor, I think, would we see writers as a vital and irreplaceable profession (cf: lawyers, doctors).

We wouldn’t even think of graphic designers quite the same way, though their ability to do what they do has become equally parlous, a race-to-the-bottom free-for-all on the Internet where someone in the developing world will oversee an entire rebrand for ten bucks. But graphic design is a specialised set of skills you need to do particular training for. Writing gets the ‘fake career’ tag. Writing is something we all more or less learn with rote precision at primary school.

(That’s where the cognitive dissonance sits for me: I get a kind of real pleasure and real happiness out of reading a great essay or review or feature which I don’t from many or most other things. I get it from people who write about VIDEO GAMES, for God’s sake. But virtually every time I’ve written as a working adult I’ve felt a sense of shame and embarrassment – like I’m wanting a financial reward for something I cracked when I was five years old, the act of assembling sentences about what I love and hate).

But even as I wrangle with that shame, I don’t agree that anyone can write. I don’t agree that good writing is easy (though the finished product should always look like it is). I think getting reimbursed for your time tends to make okay writers buck up and discipline their work (the Internet’s epitaph could be “Cool Stories, Loosely Bound”).

And I’m really not big on the flip-as-fuck response that people who expect to be paid properly should be expected to create something of market value to do so, because those goalposts are moving awfully fast. What was once easily leveled at the strawman sighing-and-wilfully-idle poets then got cast at the people who wrote about film, music, or theatre (even if they did so imaginatively and knowledgeably). Then it got cast at the people who wrote less-read longform or investigative pieces that called for things like budgets or retainers. Now it’s being used against people who do the fundamental basics of editing and day-to-day reportage because no one wants to employ them. And if we duck outside the world of people typing into Word documents at this point, there are people with mechanical and aesthetic skills I cannot dream of and they are giving those skills away for less than they need to prosper.

The nub of the matter is that “find something else that you’re good at you can get paid for” is a little bit like hopping from ice floe to ice floe as the temperature heats up. The digital age has boosted productivity, it’s boosted GDP, but job growth has stuttered and stalled along with its mate, median income (a diagram of the US situation here). Struggling writers of most stripes are the first intrusion of harsh reality into a world of relatively comfortable and educated roles – positions that everyone assumed would always exist. Their fate signals the wider message clearly: an education won’t save you.

The ways out or through aren’t easy. Paul Krugman, as consistently a kind and compassionate voice as any, sees the widening gaps, the kids coming through with big degrees and small futures, and – well, he favours coping mechanisms:

“If the picture I’ve drawn is at all right, the only way we could have anything resembling …a society in which ordinary citizens have a reasonable assurance of maintaining a decent life as long as they work hard and play by the rules — would be by having a strong social safety net, one that guarantees not just health care but a minimum income, too. And with an ever-rising share of income going to capital rather than labor, that safety net would have to be paid for to an important extent via taxes on profits and/or investment income.”

I agree with Krugman up to a point, but what’s left hanging is exactly what that decent, hard-working life involves. All of the technological developments point to the utopian visions of mid-20thcentury robot butler sci-fi – a life of enlightened idleness while the machines do the heavy lifting.

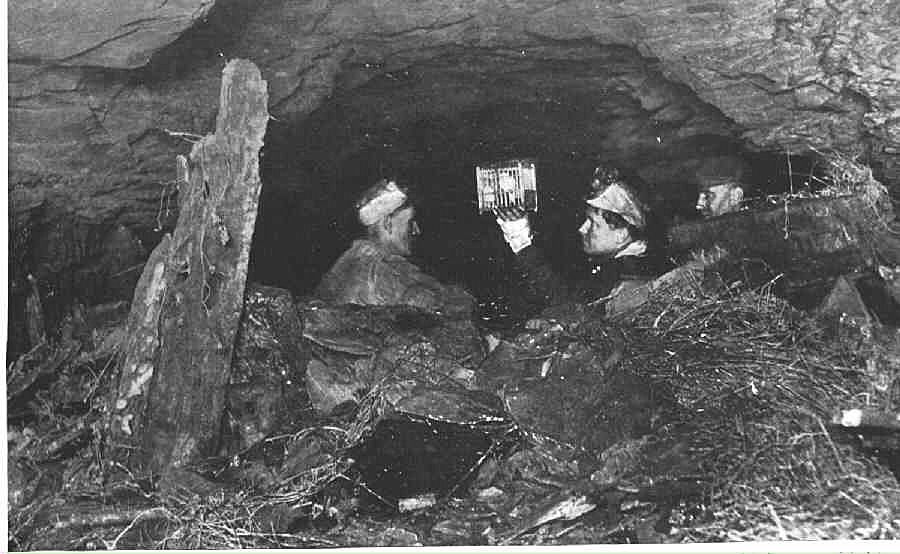

But how the move (culturally, politically, ethically) towards an actual economy that can accept and factor the obsolescence of a huge chunk of its workforce will work is a huge unknown. If those of you who are best at thinking, structure, and rhetoric need to occupy a new role - if you don’t have local beats or artist profiles to write about anymore – it could involve figuring out exactly what this new world should look like, and making it work for you. A canary in the coal mine that’s got the only map out of here.