I'm Feeling Lucky: The Camel Farm

Kirsti Whalen on using helpx.net

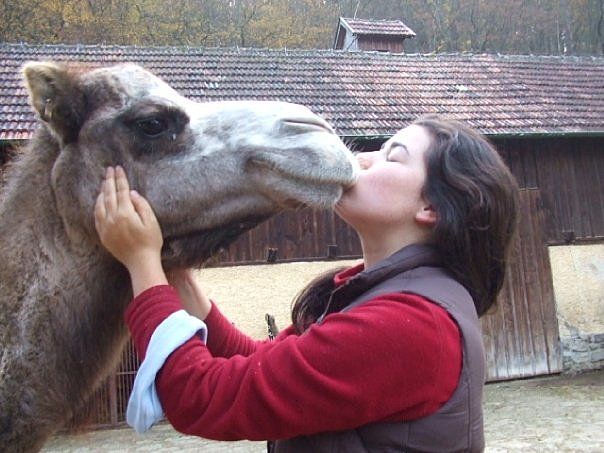

It’s 3am in Austria, and my arms are wrapped around a camel’s neck. He’s called Skye, and four hours ago I was illegally bootlegging him across the German border. An angry young stud of a camel had chased me down on my horse that morning, and it was decided that he was too violent to be kept on the farm. So we drove him across the country in a horse float (camels are out, but there’s no immigration fee for rendering a horse across a national border) and traded him for Skye, who refused to do the tricks his German circus master had desired. Skye is a gentle soul. I can tell from the soupy sadness in his huge eye and the way he leans into me, instead of away, when the vet jabs a large needle into his buttocks.

Skye has a cough, and since the vet lives three doors down, he was happy to come. Or, if he wasn’t happy, he was bound by obligation: this is a very, very small town (population: nine) and the camel farm is his primary source of income.

I became a camel trainer through a potent mix of hedonism and nihilism. My mother died when I was nineteen and I’d been her carer. Without her, I was suddenly redundant. The year prior, while she was in a brief remission, I lived in Scotland for a five-month stint as a nanny on a strawberry farm. I met the family online through easyaupair.com but in the end, I came to be adopted by them as a sort of useful, bumbling older child. So it was back to Cairnie Mansion and berry-stained fingertips I went after my mother’s death.

But the job at Cairnie only lasted for the summertime – the kids went back to school in September, and no longer required my care. Without a British passport or a work visa of any kind (I was being paid under the table for crafternoons and bake-a-thons with the kids of Cairnie) I needed to find a way to live on my limited budget. I turned to a website called helpx.net, where hosts offer accommodation and food in exchange for help on their varied properties and projects - sometimes organic family farms, sometimes meditation centers in scrubby paddocks, sometimes camel farms in miniscule towns in Austria.

Helpx works on a review system - when you leave a host, you rate them out of five stars and write a paragraph about your time there. The hosts can then rate and assess you. Future hosts and helpers have full access to these profiles, and the writeups serve as a map in deciding where to go next. It’s a loose sort of safety net, and clearly not a science: every now and again you’ll see a response to a particularly acerbic review, claiming slander, that it’s all meaningless lies.

The camel farm has received a mixed response. I understand why. In the first week I spent there I cried every day, from fear, exhaustion and the palpable disapproval of my host, Gerda. I didn’t know, then, the kindness that was to come. I didn’t know how gentle camels could be, if you gave them reason to respect you. Or their trainers, for that matter. It took me three weeks to touch one of the camels without him frothing at the mouth and rearing for a kick. It took me even longer to see Gerda as she really was.

The internet is such an instant place, and the people who scrawled insults across Gerda’s Helpx page the moment they left the town seemed to speak to this. In the wild, Lonely Planet-fuelled rampage that most backpackers engage in across Europe, there isn’t a lot of time to be unhappy and move through it. A bad hotel gets a negative rating within minutes; grumpy waitstaff get lambasted across social media. And maybe some of the people who wrote about Gerda were right. It’s not the place to travel if you don’t want to work hard; if you want to eat well and sleep in. Perhaps it’s more of a catchment for lost souls. I think there are plenty of those out there, stuck behind screens or checkout counters, looking for a more visceral adventure.

My adventure didn’t actually take place on a farm, per se - Gerda rescued the animals from travelling circuses and shows passing through the country. Most had been harmed and were terrified of people, and Gerda gently trained them to trust enough to be used for riding in the disability program she pioneered. She had a few side projects - camel rearing for the hobby camel owner, for example, camel treks in the hills for those simply interested in giving it a go - but the on-site elastic factory her husband ran and the daily therapeutic rides formed the foundation of the project, and the village itself.

It all sounds like fable, which exactly why I chose to go there. I emailed my father, all the way back in New Zealand. I’ve decided to go to Austria and work on a camel farm, I wrote. There was no reply.

I arrived at the train station near Eitental at 1am and was collected by a woman with a large dent in her forehead and copious amounts of straw proliferating from beneath her knitted hat. Gerda took me home to a room I shared with a python, loosely imprisoned in a glass terrarium in the corner. Naturally, it was a restless night. But I had to be awake at 5 anyway, to grind grain into different mixtures for the various palates of the 12 camels and fourteen horses and ponies in the yard out my bedroom window. It was autumn in Austria and very, very cold - I wore three pairs of gloves to protect my hands in an icy shed in the dark. I warmed up during the following three hours, mucking out 26 stables with a wheelbarrow and a shovel. (When I left the farm I posted a photo of my muck pile on Facebook. No one liked it. But I had shovelled several hundred kilograms of shit during my time there, and I’d earned the right to be publically proud.)

That first day I learned the routine of the following months: rise at 5am. Pull on all my clothing. Grind grain. Put collars around the neck of each sleepy camel. Tether camels to posts so they would not fight over food. Place buckets of food on the stone yard and shimmy them towards each camel with a boot, so they wouldn’t bite me in their excitement. Muck out camel stables while they chow down. Lead camels back into their yard. Fork hay down the hay hole and into a line beneath an electric tape. Watch the camels eating for a moment: old Sheehap with her collapsed hump; the squished, puggish face of Inshallah. Lead the horses from their stables. Tether. Feed out grain and mounds of hay. Muck out stables (two hours). Let the horses into the big field. Then I ate as much as I possibly could as fast as I was able, since Gerda’s whim dictated when every meal was over. She would glance out the window, see a stray cloud, llama or gambolling dromedary, and suddenly we would be on horseback, galloping away into the hills.

Midmorning, Gerda and I would spend time with the baby camels in their own house in the far paddock. In the few months I spent on the farm I managed to saddle and ride a baby dromedary who came to Gerda so abused that the mere sight of a whip would make him rear onto his hind legs and spit, thrashing around his stable and into the concrete walls. I thought that carrying a whip would help me to protect myself. But hurt things don’t need to be fought. They need to be won.

In the late afternoon, Gerda would take me for horse riding lessons at a local stable. She was a hard, stoic sort of woman: quick to criticise any mistake, sharp with a riding crop and difficult to glean emotion from. The dent in her forehead was the result of a brutal kick from a horse she had been trying to soothe. It put her in a coma for six months. She carried all the blame, maintaining that animals respond to the things we carry, and cannot be reined in with fear. I think the afternoon horse riding lessons were a kind of gift from Gerda. She would never have said thank you. But the harder I worked for her and the more calloused my once-soft hands grew, the more she gave to me: not things, but stories. Not kindness, but skills.

The night before I left for my next Helpx assignment, Gerda and I packed into the car and drove along the edge of the Danube. She refused to reveal our destination.

We arrived in a neighboring town, at the house of an old and stooping man. Gerda wrapped an arm around him and tucked him into her side, and together they led me up the road to the cemetery.

We arrived at a particular headstone and the man began to speak, with Gerda translating. “This is the grave of my son,” he said. “He was paddling across the river in a boat with his fiancé when they were caught in a current. The boat flipped and they tried to swim away, but the water was too strong and he drowned.”

Gerda placed a candle on the grave, and lit it.

“If I had known that he had drowned,” she said, “I never would have kept swimming.”

On the drive home Gerda pulled into a pocket by the side of the river. “I don’t know what happened to you,” she said, “but you carry your sadness and it’s too heavy. I have so many animals because each time I see one that is lost, I think it might be the soul of the man I loved. When I realize it’s not, it’s like losing him all over again.”

“Don’t become a sad old woman like me,” she said, pulling back onto the highway. “You are alive, and whoever you lost wants it that way. So live.”

Feature photo credit: Evgeni Zotov

The Pantograph Punch presents:

I’M FEELING LUCKY

Q Theatre Loft

8.30pm | Wednesday 24 June

All profits go towards paying our writers