On The Art of Spectacle with Singin' in the Rain

Sam Brooks talks about how to bring creativity into bringing spectacle to the stage in Singin' in the Rain.

It’s a big deal when a show like Singin’ in the Rain comes to New Zealand, so much so that it’s become a yearly event. Be it Wicked or The Sound of Music or Annie, when an international Civic-filling musical touches down on our shores, people get excited. There are billboards, there are images hanging from streetlamps, there are posters on buses and bus stops. People know that a musical is coming.

As a theatre person, I nerd out when I hear that Angels in America is being put on by Silo, or when a new company at The Basement is putting on Abigail’s Party, but there’s a part of me that tingles when that annual musical comes to our shores. We don’t get that kind of show in this country often. Even the yearly Auckland Theatre Company musical, a highlight in many theatregoers calendar, can’t deliver the kind of spectacle that these international productions do. We don’t have the foundation to support productions like that; we don’t have the money, we don’t have the audiences and frankly we don’t have the training.

We get it in movies all the time in this country: it’s why people block out entire days to go to three screenings of the new Marvel film. We don’t get that in theatre, especially musical theatre. The musical theatre scene in this country is too small to support the bigger musicals that lurch shamelessly for the audience’s heartstrings. You can’t do Mary Poppins on a thousand dollars and a general rig. Hell, you can’t even do Rent on that.

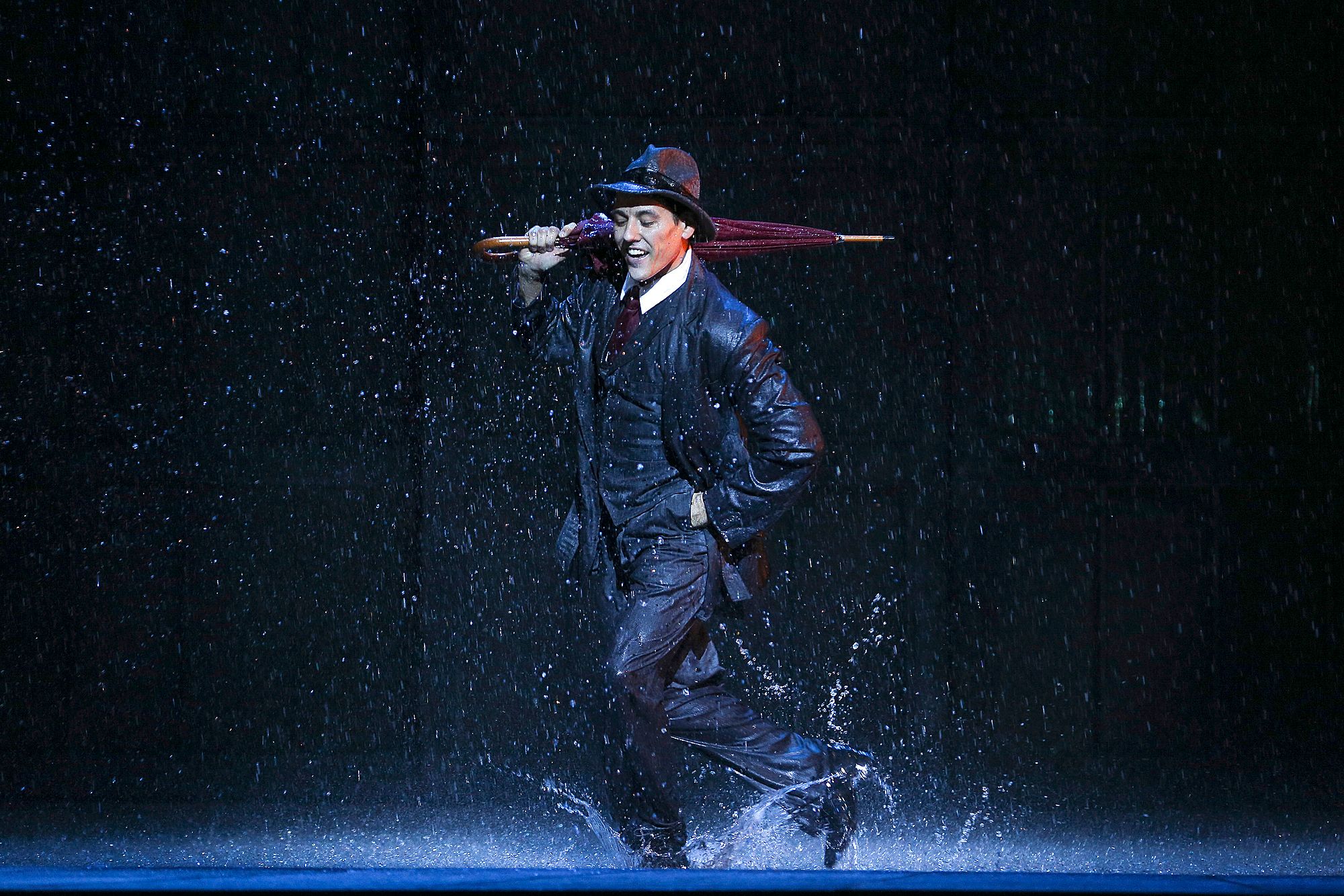

The bigness of it is what makes the spectacle of Singin’ in the Rain so special. And make no mistakes: this is pure spectacle. It takes the classic film, with the necessary screen-to-stage alterations, and blows it up on every axis. Every musical number is bigger, every lighting shift is felt somewhere deep in your body and every athletic feat is happening right in front of you.

There is a very visceral, primal joy in seeing twelve thousand litres of water pour from the ceiling and seeing a performer dance and splash that water onto the first four rows of the audience and it’s the kind of joy you won’t get sitting on an uncomfortable couch in a thirty-seat theatre. For reference, twelve thousand litres of water is twelve spa pools of water, or sixteen thousand bottles of wine. It is a lot of water.

It’s easy to dismiss something like this as empty calories, but that ignores the creativity and craft that goes into a show like this. It’s fun to watch twelve thousand litres of water tumble from the roof, but it’s even more fun to figure out how they did it, and how they’re going to do it every night across multiple countries.

It made me wonder how someone can bring their own creativity to something like Singin’ in the Rain, a show that not only relies on spectacle, but relies on the particular spectacle that the audience is expecting. If you see The Lion King, you want to see the big giraffe puppet; if you’re seeing Wicked you want to see a witch fly to the top of the stage; and if you’re seeing Singin’ in the Rain, you want to see Gene Kelly or some approximation thereof dancing in the rain.

With a show of this scale, there’s another challenge to the creative process. When you’re dealing with a pre-existing property, you run the risk of not meeting an audience’s expectations. If you’re seeing a straight play, this isn’t as dire or key to the audience’s enjoyment. Nobody went into Silo Theatre’s production of Angels in America expecting Mia Blake to copy-paste Emma Thompson’s performance. But with a musical as beloved as Singin’ in the Rain, there are expectations that you have to deliver. It’s the same expectations that greet any popular material being adapted to the stage, or to the screen. An audience expects the title song, an audience expects dancing, an audience expects to cry during You Were Meant For Me.

But when you’re a creative person, how do you bring your own skill and creativity while staying true to the musical, but also what an audience expects of that particular musical?

Robert Scott, the musical supervisor of the show, is emphatic that preserving the spirit of the original show is important. “You’ve got a responsibility to serve the piece as well as the movie because people come expecting to hear certain things and that’s what we have to provide.”

There is an immense amount of skill and creativity involved in this process of staying true to the original musical. It’s not a matter of just copying the film, zooming out of the picture, and putting it on a stage. They’re two different mediums, sixty years apart, and considerations have to be made. An example of this is translating the sound of the musical. This production has an orchestra of ten, which is almost nothing compared to the eighty-person orchestra of the film, a size that was financially viable in the last years of the Golden Age of Hollywood. However, if you’re touring a show with a twenty-nine-person cast and eighteen-person crew, adding an eighty-person orchestra is financially unviable and probably impossible in many theatre spaces.

Scott speaks of this particular challenge, “It’s trying to re-create the feel and sound [of the musical] but in a much more condensed way. An American orchestrator called Larry Blank came in, did the reduction and did lots of other work to make the musical coherent … and it’s his work that we’re trying to reference and bring to life.”

The orchestrations are a subtle example of where creativity has to be brought into this particular process. A more obvious example is use of water in the show; ‘twelve thousand litres of water’ is basically the tagline of Singin’ in the Rain, and the work that has gone into this part of the show is an alchemy of science and creativity. It happens during the most famous, titular number from the film, and the anticipated first act closer of the musical, where Don Lockwood sings about the joys of, appropriately, singing in the rain.

Jonathan Church, the director of the London revival, talked at length about perfecting the use of water in the show. “We flooded the stage to a depth of two or three inches so in the rehearsal room you’re creating a dance that you have no idea whether you’re going to be able to do it or not in the space.”

The rest has been a careful process of scientific refinery. To avoid giving the actors hypothermia or other temperature-related diseases, the water is heated to thirty degrees. However, as anybody who has been to a public swimming pool will know, this is the prime temperature for bacteria to spread, so the water is then filtered and re-treated for re-use the previous night.

Beyond that, the material that the water falls onto had to be worked out. It not only had to withstand thousands and thousands of litres of water in a show, but it had to do so throughout a long tour. Church laments this particular process, “We found one version of this material that seemed to be good but when it got wet a few times it got brittle. The force of the tap shoes started shattering the plastic. We had to replace the whole floor!”

This kind of creativity has to be brought to every aspect of the musical, from the lighting to the choreography (Scott proudly says that almost none of the choreography is from the film) to the insane Broadway Melody number, which in the film feels like a departure but in this production is a clear highlight, featuring a kaleidoscope of performers at their athletic best, a masterclass in the synergy between lighting design and choreography and a cannonball of orchestration.

It’s the kind of pleasure only a show like this can provide. We love seeing spectacle. It’s why Fast and Furious 7 has grossed literally a billion dollars already. It’s why Wicked has a place in so many hearts across the world. It’s why everybody hates the days that come after Guy Fawkes Day.

A show like this is special to the general public. It’s easy to praise something raw that somebody put on for fifty cents, including publicity, for three people in their lounge. There’s nothing wrong with those shows, and I love them very much. But there’s room for spectacle in theatre too, and we get so little of it that’s it worth grabbing while you can. It’s often the most direct way to your heart, and it’ll be the thing they remember most about the show when they leave it.

The brilliant thing about musicals, and this musical in particular is that it plays on nostalgia. Whether you’re a retired banker in Auckland, a BA student in Australia, a copywriter in New York or someone who just really likes musicals, there’s an experience to share in here. Singin’ in the Rain recreates some of the most magical moments ever put to cellloid, and blows it up a thousand times.

It’s the spectacle in Singin’ in the Rain that deserves to be applauded, and the creativity, craft and hard work that goes into it is even more worthy of applause. It’s a reminder that some of the best, most inventive and bracing work we’ll ever see on a stage can be under the guise of a man simply dancing in puddles in the rain. It’s a special thing, and deserves to be cherished.

Sam Brooks travelled to the Wellington premiere of Singin' in the Rain, courtesy of Auckland Live.

Singin’ in the Rain runs from 1-24 May LIVE at The Civic

Hashtag: #SinginNZ

For information and to buy tickets, click here.