Te Toi o te Ātetenga: The Art of Resistance

Rangimārie Sophie Jolley explores Te Toi o te Ātetenga: The Art of Resistance, to understand wāhine activist art as a platform to protest and highlight Tino Rangatiratanga.

When you think Māori art, what comes to mind? I think of the magic used to weave together threads of the past, present and future. I see te pō in every colour black, te whaiao in every red, te ao mārama in every splash of white. I see the tino rangatiratanga flag blowing in the wind and Robyn Kahukiwa’s subjects with their heads tilted in an ode to whakairo. I see the subtleties of change, and bold declarations of resistance. And the only reason I see that, is because of the work wāhine Māori have done to create these moments for us.

Wāhine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga – The Art of Resistance, curated by Suzanne Tamaki, alongside co-curators Robyn Kahukiwa and Tracey Tawhiao. The work is a collective showing of our most influential change makers. The show is having its second viewing, having left Tāmaki Makaurau to take pride of place in the Wellington Museum gallery space.

In sharing this body of work, we are gifted an opportunity to look back in time, and perhaps, see our way forward in these pou of Māori visual art. When we look back, we conjure their images to mark our passage in time. What if Robyn Kahukiwa had never changed the direction of her subjects’ heads, bringing the angle of tekoteko into the contemporary canvas of our collective memories? What if Linda Munn and her collaborators had never brought strands of red, white and black together to create the fabric of tino rangatiratanga?

Would we know ourselves, without the change they created for us?

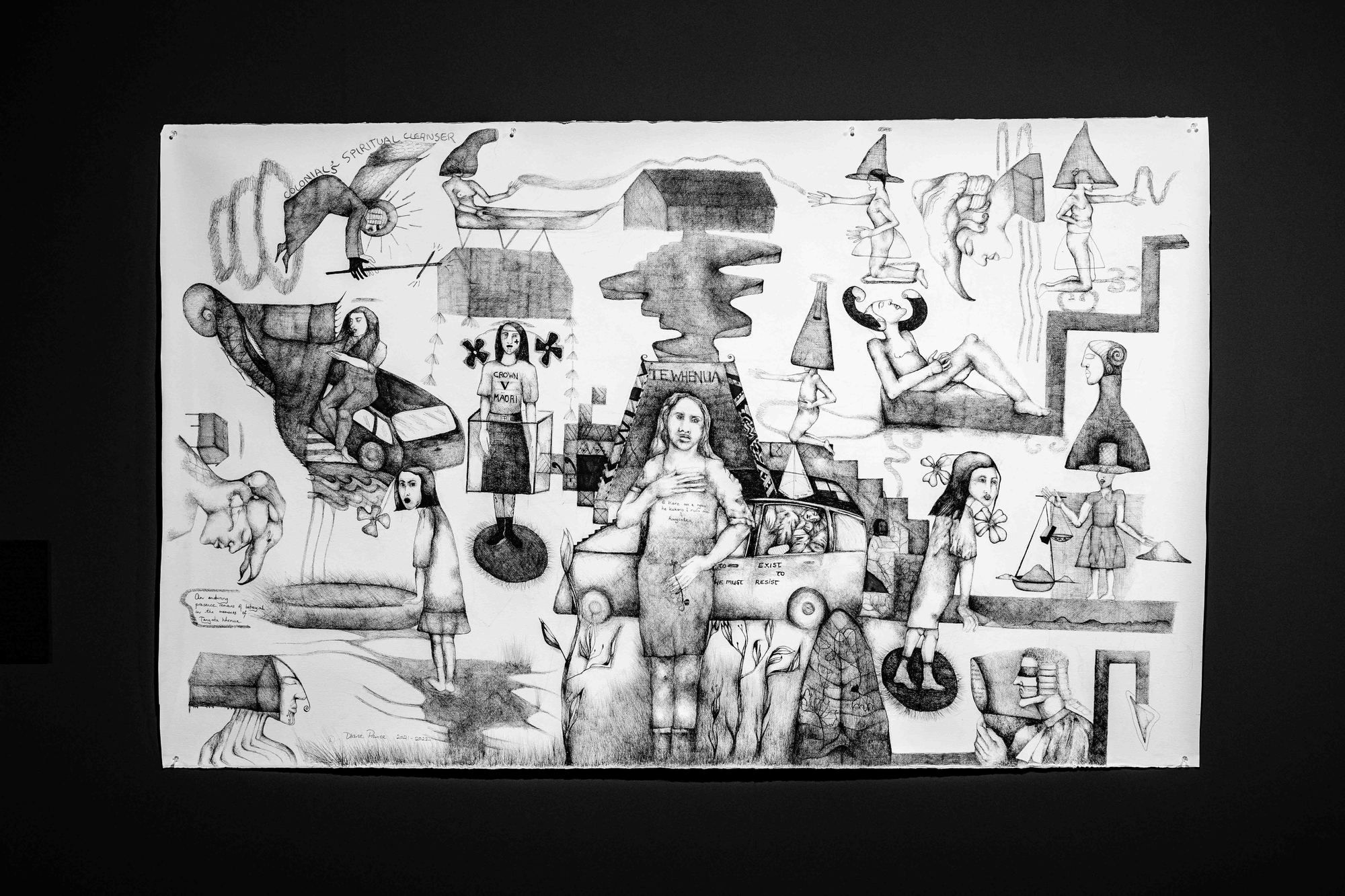

Exhibition image of Wahine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga | The Art of Resistance, featuring work by Suzanne Tamaki. Image by Trinity Thompson-Browne

Robyn Kahukiwa’s faces and the positioning of her subjects’ bodies have cemented themselves in our minds. Her stylised nod to whakairo within the contemporary context of canvas is present in this body of work. In Genealogy Stick, she depicts whakapapa as our connection to everything and, in the face of resistance, a source of great strength. In her second painting, Family Group, she tells a dark tale of the challenges our urbanised whānau continue to face in our lived realities, such as homelessness, gentrification and the disconnection we experience in our own whenua.

But there are many ways to face the challenge. Curator of the exhibition, Suzanne Tamaki is a bold activist. Her works are direct, to the point and often speak to the exact moments in time when change occurs. In 250 years of colonisation and we are still fucking protesting, she wields boldness as an affront to the monuments of colonisation within our city.

Another who’s not known for her subtlety is the legendary force that is Linda Munn. Yet , Munn’s use of shadow, shrouded figures and deeply knowing eyes in the portrait series To Take Possession of Another’s Goods 1 & 2 are hauntingly subtle. Her contributions to the fabric of Māori art are well known, and it’s the strong presence of whakapapa and interconnectedness of all, of transition across generations and the intimacy of the conversation between generations that will stick with many.

Exhibition image of Wahine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga | The Art of Resistance. Image by Trinity Thompson-Browne

In seeking the liminal, Dianne Prince provides a sense of movement and language across a clear white space. Her works are a revelation of the relationship between coloniser and colonised, using beauty and pain together to create something truly unique. Our relationship to change, to the past and its effect on the present, is palpable in her works.

Throughout the collection, this theme presents itself over and over – the past is the present, the present is the future, and all of it collides in the mauri of the imagery they gift us for today. The wielding of this mauri by Tāwera Tahuri’s kurī is a masterful execution activism plays in creating safe spaces. Its playful, enigmatic presence is an incredible representation of the role kaitiakitanga plays . The artist is a known legend in the arts realm for her practice of pushing boundaries. It makes me wonder whether the kurī was positioned in the right space. But regardless of its positioning, its presence stood out.

Exhibition image of Wahine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga | The Art of Resistance, featuring an installation by Ngāhina Hohaia. Image by Trinity Thompson-Browne

Andrea Hopkins tells an incredible story, and activism is intricately hidden amongst a thousand moments. Within her works, the viewer finds trails and hints at the tip of each flag hung, each movement of an arm, each knot upon a pou. This is an artist who knows how to enchant an audience, and whose activism isn’t subtle, but is deep. Whose presence in time is not trapped, but woven.

With the room palpitating, artist Kura Te Waru Rewiri’s introspection are a welcome repose for the senses and offer a shift of perspective. The use of colour, shape and distance to create the movement of an idea within the viewer’s mind is simply beautiful. Her contributions to the artscape are mammoth, and the nuance she wields into this space is reflective of how multi-faceted activism can really be.

Natalie Robertson’s photography installation is further proof of the gentleness of change – she uses te taiao on her hands to demonstrate the depths to which change can occur, and how personal that transformation can be. Her use of kōhatu (rocks), whenua (earth) and greenery to demonstrate the fragility and strength of our natural environment, and our part in maintaining that fragile balance, is a wonderfully soft and intimate respite in the face of great challenges.

Exhibition image of Wahine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga | The Art of Resistance. Image by Trinity Thompson-Browne

Amongst the works, Ngāhina Hohaia’s piece is a stand-out contribution. By repurposing old fence posts with the loaded history of the artist’s whenua, Ngāhina transforms the entire space. . The red and black paint adorned with white Raukura, a symbol significant to people of the Taranaki rohe, in combination with the positioning of these dominating pou, is a revelation. Whenua is important, and so is the ways in activism can exist upon our own whenua, our whakapapa, and the stance we take to uphold both.

Tracey Tawhiao is good at taking a stance. Her contribution to the arts has changed the ways we use shapes, colour and texture to tell a story. In this body of work, her stance is bold and loud, and gives us an opportunity to view how deep the activism really goes within our expressions of change.

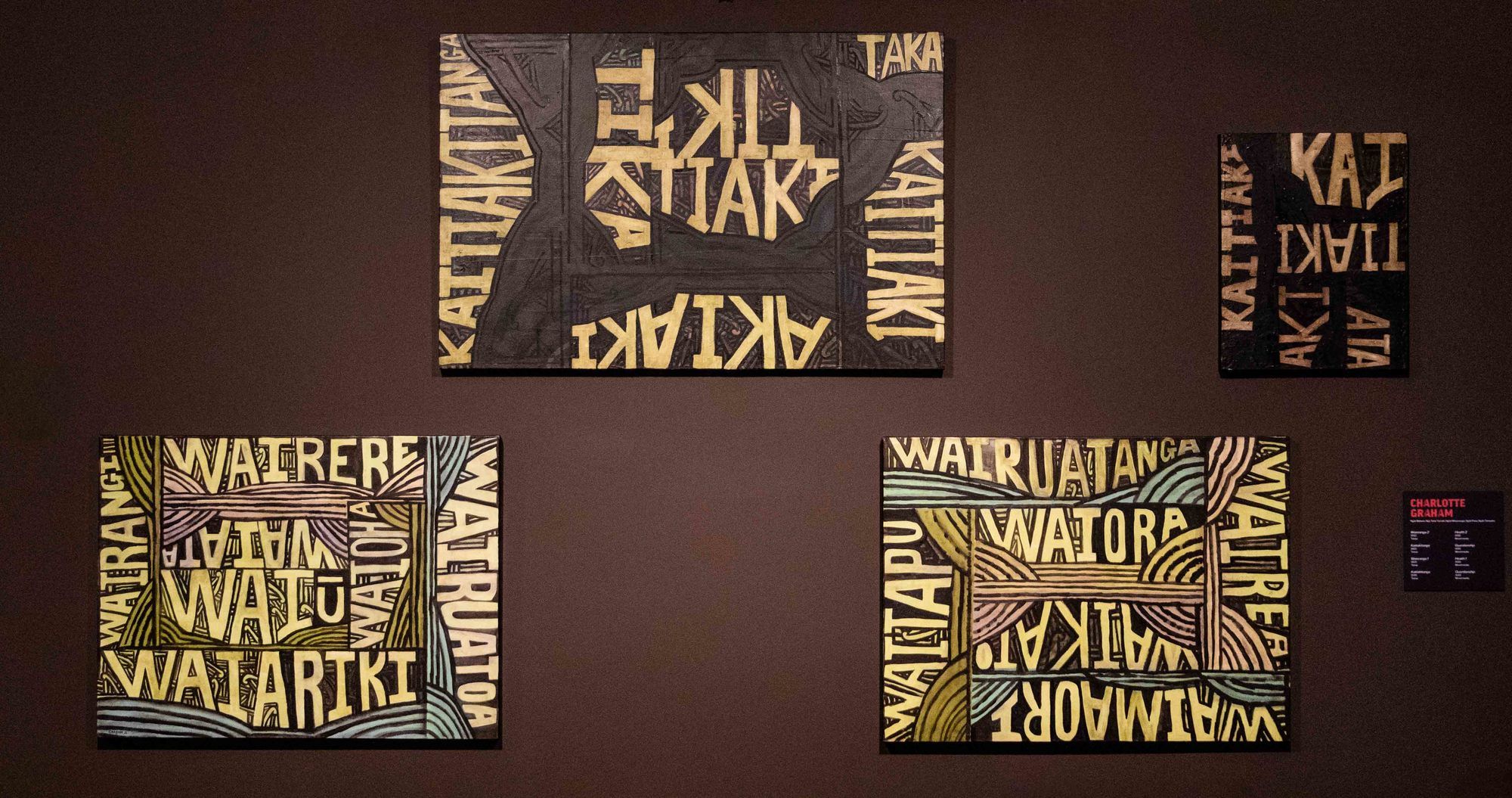

Cleansing the space, Charlotte Graham’s works twist wai and kaitiakitanga into our experience. She weaves the words in spiralised thoughts through the taiao – elements of water of bush tying the necessity of change into the nature of our humanity.

Having achieved so much already, it’s a marvel that these artists, these bastions, these pou of our artscape are still continuing to offer contributions. Their persistence to capture challenges we face, and reflect them back in such a stunning way, is a testament to the power they each individually wield. Throughout each piece, threads of te pō, te whaiao and te ao mārama are woven – and of course, that in itself is reflective of the ways in which these artists have not only shaped our minds, but our collective understanding of what activism is, and how it has existed in te ao Māori.

Without every single thread that each of these artists has contributed to our artscape, we wouldn’t be who we are today.

Wāhine Māori: Te Toi o te Ātetenga – The Art of Resistance, was curated by Suzanne Tamaki, alongside co-curators Robyn Kahukiwa and Tracey Tawhiao.

5 – 9 Oct

Wellington Museum

Header image features Robyn Kahukiwa, Image by Trinity Thompson-Browne.

Clarification: This exhibition was first presented, with support, at Northart (13 March - 15 May).