Te Kaitiaki O Ngā Tikanga Toi Raranga

Master weaver and artist Toi Te Rito Maihi on how she came to raranga, and the origins of the Aotearoa Moananui-a-Kiwa Weavers Hui.

This essay by Toi Te Rito Maihi (Ngāi Te Ipu, Ngāi Te Apatu o Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāpuhi) is from Te Manu Huna a Tāne, edited by Jenny Gillam and Eugene Hansen (Massey University Press, June 2020).

I was fascinated when, aged seven, I first saw my father weaving a kete. He would throw the kete behind him as soon as he saw me. As I was fair skinned he was determined I would not do anything that marked me as being Māori. This was despite the prediction made at my birth — ‘She will bring the mana back to raranga’ — by the group of kuia waiting outside for my father to show me to them. They asked what he had named me. ‘Toi’. And as his surname was Te Rito the implications were clear. Apparently when they became too excited my mother grew anxious and asked Dad to bring me back.

At that time it was not unusual for Māori parents to encourage their children to take on Pākehā culture and to minimise their own kaupapa in an attempt to thrive in a colonised world. My father was clearly trying to live in both worlds. During my childhood I remember occasions when Dad had the time and the need to weave — we would put up with having to bathe standing in the copper due to the bath being full of kōrari soaking in water to soften it as part of its preparation for raranga.

Often the tamariki didn’t know their mother could weave!

Despite my father’s resistance, and without his knowledge, my Pākehā mother, with her terrible accent, had taught us a little te reo Māori. She thought that if we won a scholarship to a Māori college, his pride would not let him turn it down. So, on my twelfth birthday I started at Queen Victoria School, an Anglican boarding school for Māori girls in Auckland. Here I met my lifelong friend Connie Tuaupiki. She was fluent in both te reo and English. To my joy, we were introduced to tāniko, a twining technique used by Māori to make the patterns commonly seen on kākahu used in the past. I noticed that the girls were all wearing tāniko tātua, and I realised it was the older girls who were teaching the younger girls. The patterns all consisted of stripes, diagonals or diamond shapes, and yet with 80 girls there were 80 different patterns. In those days hapū would use only the patterns that their grandmothers had taught them so I was amazed to learn that there were so many variations within a hapū. I took my first piece home to my mother. She put it around the crown of a pōtae made by Tupanapana, my grandmother’s sister.

As the years passed, I continued my passion for raranga — sometimes if I saw a beautiful kete being carried by someone (although this was rare in those days) I would follow them and strike up a conversation. One kete was so unusual that I followed it in my car for some miles. When the woman stopped I introduced myself and we discovered we both had boys in the same boarding school! She showed me the beautiful whāriki woven by her mother from which she had taken the pattern.

As my interest in raranga grew I started to recognise that houses with neglected kōrari planted in their surrounds indicated that a kaiwhatu had lived there but was now too old to care for the plants. I would visit the houses, hoping that the whānau had kept some of her work and would be happy to show me. Well cared for kōrari indicated a kaiwhatu living and using their kōrari. These homes were well worth a visit, and sometimes they knew of other kaiwhatu I could visit and learn from.

What shocked me, though, was that often the tamariki didn’t know their mother could weave! The need to have many tamariki to replace those lost through the land wars with the Pākehā meant that wāhine had no time for raranga. Although their mothers wove items such as whāriki for the floor and kete to hold the fruits of the garden, they had dropped these skills while busy with their own tamariki. When their tamariki left for the cities, only then could they return to raranga. But when the tamariki were visiting they would pack it away, so the tamariki didn’t know their mother could weave!

When I was working as a primary school teacher, I was awarded a month’s leave with pay by the Department of Education to pursue my interest. I took the opportunity to graph the tāniko patterns of two kākahu in Auckland War Memorial Museum that had long fascinated me. I was intrigued to see that the kaiwhatu had on occasion divided an aho to make an extra stitch — necessary to make the pattern. Summoned to bring my findings to show Ngāpuhi kaumātua Taru Rankin, who had, unbeknown to me, been following my pursuit of knowledge, I spread my graphs on the carpet in front of him. He spent some time looking at what I had done, then he asked me, ‘What if you stepped into the pattern?’ My answer: ‘I’d be part of the pattern. It would stretch to infinity all around me, above and below me — I’d be part of the pattern!’ He was pleased with my answer, and gestured for food to be served immediately. Later I drove home with my mind awhirl! Now I knew why I hadn’t yet met anyone to teach me raranga. I had first to understand the patterns of tāniko.

An older name for whenua is Io — the omnipotent one. So when you wear a kākahu, the Io is against your skin.

The years passed. Wherever I was tutoring raranga, from Foveaux Strait to the Far North, I would spend the money I’d earned on a cheap rental car and would visit small and large museums. I would visit and listen to somebody’s whaea, nana or kaumātua, or anybody else with an interest similar to mine. I found a wealth of information from these knowledge-holders, for which I have always been grateful. I appreciated their caution and their careful assessment of me as someone whom they could trust to share their knowledge.

I would learn the significance of the aho and whenu. Aho is a word for connection, which makes perfect sense when you see the aho connect the whenu. Whenu is thought to be an abbreviation of whenua — the Earth that sustains us. Whenua is also the name for the placenta that sustains us before birth. An older name for whenua is Io — the omnipotent one. So when you wear a kākahu, the Io is against your skin. And the aho, that connection with all of the elements that you live among and learn from, and the knowledge that you then hand on, it’s all there when you put the kākahu on.

I became a member of MASPAC (the Māori and South Pacific Arts Council). Ngoingoi Pēwhairangi called a meeting of wāhine she knew who were involved in raranga. I was one of them. Ngoi was an exceptional, gifted wahine in many spheres and was worried about the disappearance of raranga. We discussed the need to bring kaiwhatu together so that we could hear from them about what type of support they needed.

In October 1983 we assembled at Ngoi’s Pakirikiri Marae, in Tokomaru Bay. Air New Zealand donated the fares for kaiwhatu from all over Aotearoa, from the Far North to a lone representative from Stewart Island. But many came by car, accompanied by their tāne. At three thirty in the afternoon, buses, vans and dozens of cars assembled at the entrance of the marae of Te Hono ki Rarotonga. The whakaeke of the tangata whenua began, the kaikaranga of the manuhiri rang out. Before the wharenui a group of wāhine welcomed the manuhiri with poi and waiata. The huge visiting party came on to the marae — 160 had been planned for, and more than 400 came. Among them were Te Arikinui, Dame Te Atairangikaahu, the Māori queen, and a lively contingent from the Pacific Islands. The harirū was savoured, promising a productive weekend.

Any age is the best age to start learning, and the very best learners are those who are interested.

There were many presentations, interspersed with kai, waiata and raranga. The overarching kōrero was that you must know your materials, their use, and their conservation; and that any age is the best age to start learning, and the very best learners are those who are interested.

Emily Schuster told about the scarcity of pīngao. She was adamant that we must protect that resource for the descendants of tangata whenua.

Hine Matikotai presented about traditional tukutuku.

I showed a magnificent kākahu huruhuru, gleaming in the sun, silky in the wind, and spoke of raranga as an art form that influences all the different facets of our lives, including the more subtle aspects of spirituality and symbolic meaning.

Rene Orchiston of Gisborne felt that kaiwhatu Māori were using inferior materials, so 18 years earlier she had started cultivating a collection of over 50 varieties of harakeke, most of it sourced from kuia. With greatly appreciated assistance from Diggeress Te Kanawa, whose deft hands had slit, spliced and stripped them, Rene presented examples of some of her collection.

Digger spoke about the work she had learned from her mother, the greatly admired Rangimarie Hetet, saying, ‘I am not a teacher, but a person who shows people.’ Quietly, with humility, she described how Māori have had to overcome many things, sometimes forcing a need to break with tikanga, including the tapu of raranga work. She emphasised that, while we must now share the mātauranga, respect must be maintained to protect traditional knowledge. She spoke too of the difficulties of finding the appropriate plants for dyes. Listening to Digger, a tohunga of knowledge of the past, was truly moving.

Te Aue Davis discussed the conservation and restoration of woven garments and natural fibre in textiles. She spoke about her concerns surrounding the lack of attention to Māori fibres by restoration experts in our museums due to their emphasis on Western tapestries and embroideries, and that practically nothing had been done on the garments of the indigenous people of the land. She then demonstrated how to wash and repair damaged kākahu.

The Pacific Island women spoke of their reluctance to use Māori resources without permission. They asked for guidance about their use of harakeke rather than their native pandanus, and identified their difficulties with it being an unfamiliar, harder plant, moving and shaping itself differently from pandanus. They also wanted their children to know how to prepare and handle the pandanus.

So began the annual hui of Aotearoa Moananui-a-Kiwa Weavers, held on Labour Day weekend each year, which continues today

By the end of the hui we had agreed that an organisation should be established to coordinate and care for the interests of Māori and Pacific Island weavers, and that the hui should strongly petition for the conservation of pīngao, kiekie, and harakeke reserves by:

• placing a rāhui on threatened areas;

• allocating Crown lands for harakeke planting;

• managing the harvesting of reserves under the supervision of local Māori.

This submission would be made to the Department of Maori Affairs, local authorities, the Commission for the Environment, the Ministry of Works and Development, and conservation organisations.

The hui also acknowledged the need of the Pacific Island weavers to have a continuing supply of pandanus.

So began the annual hui of Aotearoa Moananui-a-Kiwa Weavers, held on Labour Day weekend each year, which continues today as Te Roopu Whatu Raranga o Aotearoa.

Over time, with the hui becoming more focused on sharing techniques and understanding tikanga, the older kaiwhatu who were doing much of the teaching were becoming exhausted. In addition, they were often teaching someone who lived far from them, so if the pupil became lost when weaving they had no one to correct them and had to wait until the next annual hui for assistance. So it was agreed to have smaller regional hui.

As the northern representative, I chose Pukepoto as the site for our hui. It was ideally situated and had experienced kaiwhatu in Maata Te Maru and Tottie Robson. Other established kaiwhatu, Florrie Berghan and Lydia Smith, lived nearby in Ahipara. As Maata had taught the local girls to make kete, pōtae and whāriki, there were quite a few capable kaiwhatu.

We decided a kaiwhatu with a car from each hapū should be approached. She would choose who would accompany her and be given petrol money. Kōrari would be no problem, for there was Viv Gregory’s plantation, which he had developed over the years, just across the road. For kai, we would pay a local whanaunga for a beast, and another for a couple of sheep. Another was a fisherman. He would provide kaimoana.

So it was settled. All was arranged, everyone happy.

We began alternating regional hui with national hui. We could run three regional hui for the same cost as a national hui, and we now had a great number of small groups producing very fine work.

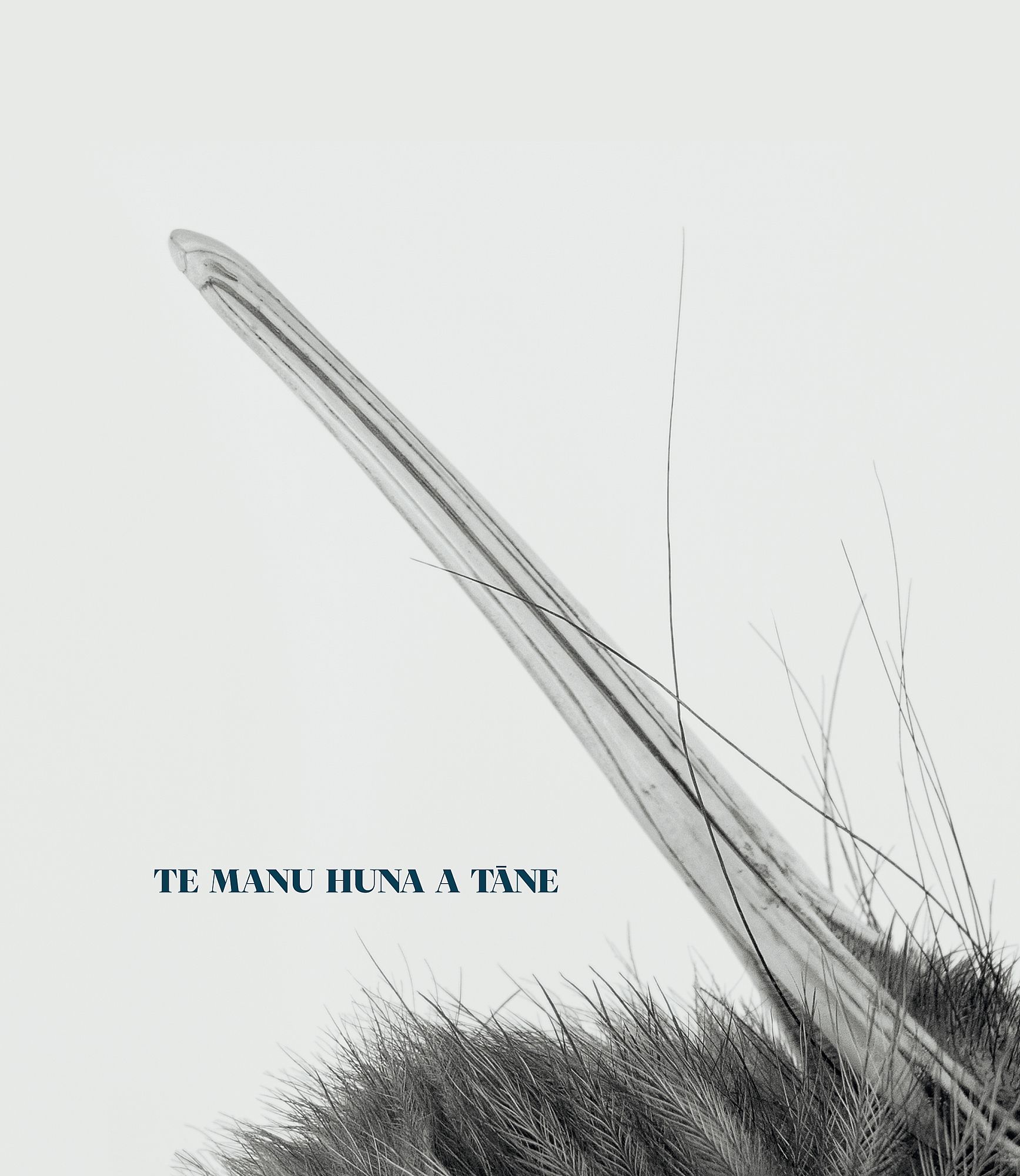

Te Manu Huna a Tāne cover image.

This essay by Toi Te Rito Maihi (Ngāi Te Ipu, Ngāi Te Apatu o Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāpuhi) is from Te Manu Huna a Tāne, edited by Jenny Gillam and Eugene Hansen (Massey University Press, June 2020).