Song of the Goddess-Twins: A Review of Tatau: Sāmoan Tattooing and Photography

Tatau was once the precious art of Samoan women, but it's now an artform dominated by men. Tusiata Avia explores the Tatau exhibition at Te Papa to find herself there.

Sāmoan tatau began with women. Two women. Taema and Tilafaiga, the goddess-twins who swam to Fiji to learn the art of tatau. When they returned to Sāmoa as the first tufuga ta tatau (master tattooists) they had a lot on their minds: tatau was for women, not for men. To help them remember this instruction, they created a song as an aide memoire. But things happen. On the long swim back to Sāmoa, and after a deep dive to a clam shell at the bottom of the ocean, the song got muddled: Tattoo the men, not the women. Tatau the men, not the women. And so tatau – the pe’a in particular – became the mark of men. And all tufuga ta tatau have since been men.

<>Curated by Sean Mallon, Tatau is a photography exhibition of Sāmoan tatau practices, showing at Te Papa Tongarewa. Mallon is also co-author of the stunning book Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing (Te Papa Press, 2018) and is a longtime scholar and devotee of tatau. He has created this vā for us to traverse. Tatau showcases work by four artists: Mark Adams, Greg Semu, John Agcaoili and Angela Tiatia.

Vā in Sāmoan means space. Not space as emptiness but space as relational. To me, vā is all things that co-exist: between everyone and everything, there is relationship.

Relationships within relationships.

Enter Tatau through the underworld of Lemi Ponifasio’s exhibition House of Night and Day. This is the right way to come. You approach tatau through a world not entirely of this one, a place that allows you to move between earth and heaven, day and night, human and aitu.

Listen closely: under Tatau there is a song that plays constantly; it tells the origin-story of Sāmoan tatau. You won’t know this unless the story is already known to you, or until you find your way deeper into the maze and discover the words on the wall, next to the au (tattoo instruments). Whether you find the words or not, the song is always present. Like many things in Sāmoan culture, the truth sits somewhere below the surface.

Mark Adams, 1982. Te Atatu South, west Auckland Tattooing Seoseo Tuigamala Tufuga tatatau: Su‘a Tavui Pasina Iosefo Ah Ken, print. Image courtesy of the artist. Te Papa (TMP035299)

Mark Adams, 1982. Farwood Drive, Henderson, west Auckland Tattooing Uli Tufuga tatatau: Su‘a Tavui Pasina Iosefo Ah Ken, print. Image courtesy of the artist. Te Papa (TMP036153)

Welcome to the vā.

Mark Adams’ work is the central vā, the door to the exhibition, from which all the others radiate. The work that greets us shows Fatu Feu’u (one of our most celebrated Sāmoan artists) in his newly done pe’a. He is flanked by the most famous tufuga ta tatau of modern times, Su’a Suluape Paulo II.

Adams is the first and longtime photographer of Sāmoan tatau in New Zealand. He has been following and framing the people, the processes and the places for 40 years. A Palagi artist, he documents tatau as it arrived on the skins of men in the living rooms and garages of Auckland in the 1970s and 80s.

<>I make my way around the works and am suddenly taken aback to see one of my uncles – recently passed – grinning out from one of the photographs (10.5.1980, Grotto Road, Onehunga). He is not getting tatau but is part of the celebration after a friend's tatau has been completed. The umusaga ritual has finished and everyone is crowded around the two men with fresh tatau. Adams arranges them in a frame: men, women, children, Sāmoan, Palagi, family and friends. A photo, he felt, captured “the cross-cultural happy new nation we all wanted to build”.

I was 14 when this photograph was taken, and keenly aware that National was in power, Muldoon was Prime Minister, families like mine were being dawn raided out of their beds and into the cells by police in the middle of the night and the Springbok tour was just around the corner. I’m glad to hear that there was someone out there who was full of cross-cultural hope and happiness, but it was not the New Zealand that I lived in.

In the photograph, the party has begun. My uncle is smiling and full of fun, there is a box of DB in the foreground, a few opened bottles of spirits, a couple of packets of Rothmans cigarettes. The dead gather and look back at us. In this same work stands Tony Fomison (1939 – 1990), an important New Zealand artist, and the first Palagi to receive a tatau from Su’a Suluape Paulo II. Tatau is a doorway between this world and the next, ourselves and our ancestors, art and tradition.

<>O lau tatau: Sit in the video room with the bearers of tatau and malu and listen to them answer the question: What does the tatau mean to me? Hear these people explain their relationships and beliefs around their tatau. They express what it gives them, what they believe it means, why they chose to have a tatau:

for tautua (service to family)

for gafa (genealogy)

for connection: to family, to ancestors, to Sāmoan culture

for identity, authenticity

for bridging the gap between being born in New Zealand and our Sāmoan-born parents

for humility – to keep the malu covered

to keep the traditional way of tatau alive

to learn the fa’asamoa

to learn the chiefly, poetic language of Sāmoan oratory

to receive history

to go forward into the future from the past.

The answers thread through and over, come together and pull apart, as many reasons as there are voices to give them.

<>Come into Greg Semu’s vā. Semu is a New Zealand-born Sāmoan artist, photographer and wearer of the pe’a. His body has tatau – also by Su’a Suluape Paulo II – his body is the post-colonial body; the self-aware body, the body that uses itself as art, to make us think and feel and ask the discomforting questions. This tatau-ed body is Jesus on the cross, dying on the shocking slab, standing over the cannibals’ last supper.

The dead gather and look back at us

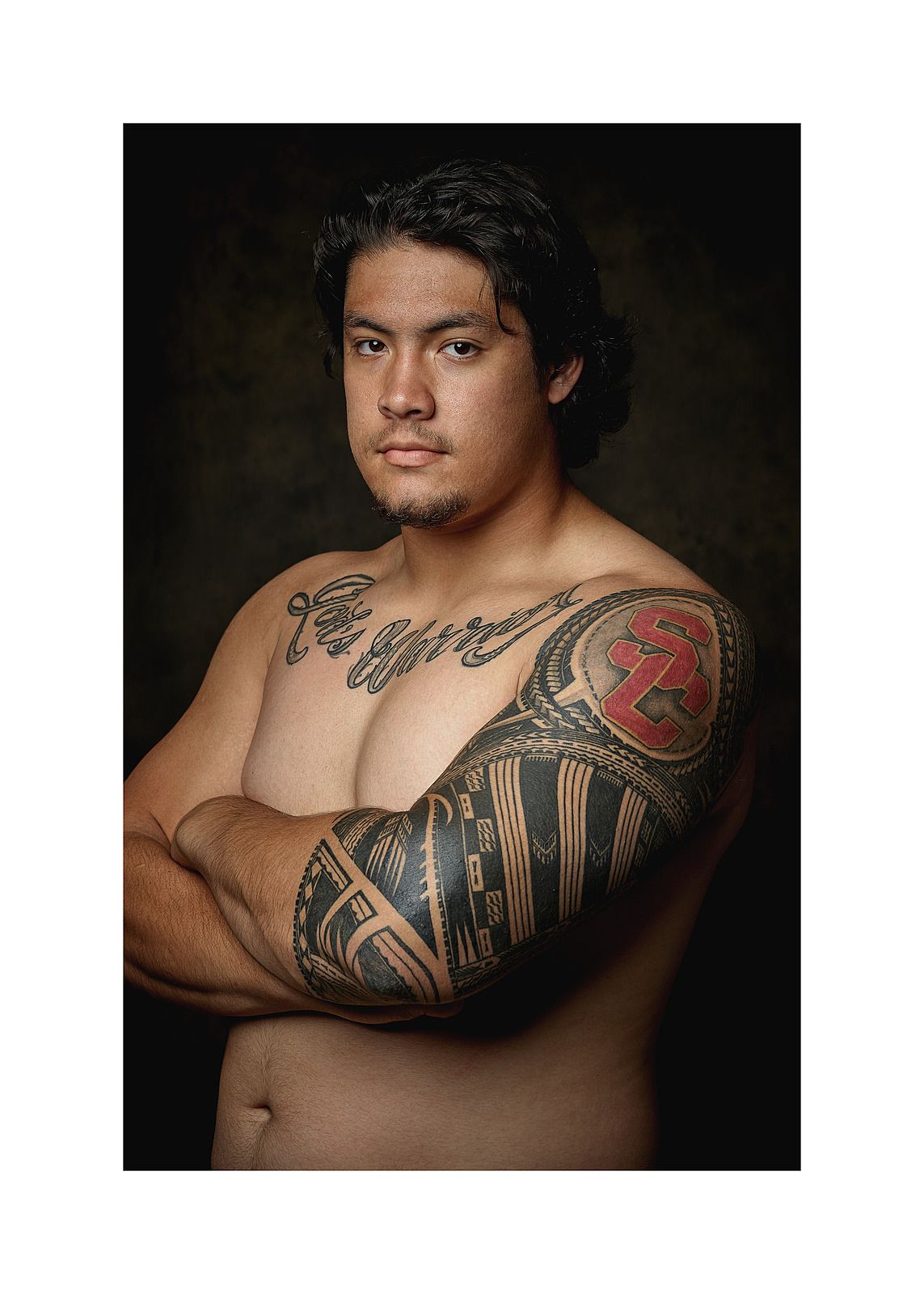

Move now to the vā that holds the work of John Agcaoili, a Filipino-American photographer. Here are tatau on the bodies of the diaspora (and those who have adopted our marks) spread far across the moana to the United States. This is the ‘new-old’, the mixing of traditions and methods and symbols. These are machine-done tatau, placed on non-traditional parts of the body. Sāmoan tatau patterns next to tigers and Latin script. All this dances together in the vā.

Vā is everything. And everything is the vā.

Tatau itself is vā. On the body it is the relational space between ink and skin, line and space. It is also the vā between those with tatau and the tufuga ta tatau, the soa, the family, the fale, the gafa, the ancestors, the spirits, the gods, the words, the histories, the cultures. It is the vā between Sāmoa and not-Sāmoa. It is our identity as Sāmoan diaspora living in New Zealand and all over the world, between the skins of Sāmoans and non-Sāmoans, between the au and the machine. It is the knowing and not knowing, the old and the new, the creation of old-new.

The vā in this exhibition (as in any exhibition of photography) is also the one between the viewed and the viewer. Some of us may walk through this exhibition and view it like any other collection of artworks.

Others, like me, move differently here.

I am a woman. A first-generation New Zealand-born Sāmoan woman. I am marked, but not with malu. I have a 34-year-long relationship with tatau (one I have been writing about for 20 years so far). I know this territory, I know many of the artworks, but I wander this vā with a slight sense of unease.

Where am I here?

I find myself in the vā that is Walking the Wall, by Angela Tiatia. A woman’s vā, a vā that questions the current space and beliefs around the relationship between women and the malu. It is here that I can sit and breathe for a while and begin writing this.

I know this territory, I know many of the artworks, but I wander this vā with a slight sense of unease

There are only three photographs of women wearing tatau in this exhibition: Karina Persoon’s tatau (a Palagi woman in the Netherlands) by Mark Adams, Foketi Lusa’s malu by Greg Semu and Tripoli Ofisa’s tatau by John Agcaoili. I sit with Angela as she climbs the white wall in her malu. The walls of the vā in which the contemporary diasporic Sāmoan woman with malu resides. She climbs wearing her malu, a black leotard, a pair of stilettos and her wild hair. She fixes us with her unwavering stare. Taema and Tilafaiga sing underneath an ocean of buses and traffic noises.

Tiatia urges us to ask the questions about women and tatau: Who? And what? And how? Who is allowed? Who gets to decide? What does it mean in this current world? Inside these skins? How can it be shown? How far have we come? How far can we go?

The last words, on some of these questions, I leave to the women of Mana Wahine, a panel of wonderful Pacific and Māori women tattooists that ran as part of Tatau on International Women’s Day.

John Agcaoili, Tattooing by Sulu'ape Si'i Liufau, 2016, print. Purchased 2019. Image courtesy of the artist. Te Papa (TMP035059)

Greg Semu, Front of pe'a, Nouma Kiriau, 1994, gelatin silver print. Purchased 2019. Te Papa (TMP035038)

Julia Mage’au Gray (Papua New Guinea, Australia) is a revelation. She contends that all Pacific tatau not only originated with women, but has always been a women’s thing. She reminds us that Papua New Guinea tatau practice predates Tilafaiga and Taema. The women of PNG are the grandmothers of Pacific tatau. She speaks of our ability – and right – to move from the old to ‘new-old’ (her term). To use what our old people did but also reflect who we are now.

Tyla Vaeau Ta’ufo’ou is the first and only Sāmoan woman to be in the process of learning traditional Sāmoan tatau. She is a second-generation New Zealand-born Sāmoan daughter of the diaspora. She is a talented and skilled tattooist in her own right (my left hand and right wrist bear testament to her skill and artistry. I count myself lucky to wear her work), and she is also apprenticing under tufuga ta tatau, Su’a Suluape Alaiva’a Petelo.

Tyla brings us full-swimming-circle back to Tilafaiga and Taema. Tyla makes her way towards becoming the first female Sāmoan tufuga ta tatau in many, many centuries – since the goddess-twins swam back from Fiji and handed the au over to the men. Tyla picks up the au from the tatau- goddesses – making the old new. Making way for all of us to re-enter the vā.

Tatau: Sāmoan Tattooing and Photography is currently on at Te Papa’s Toi Art, Level 4

Header image: Angela Tiatia, Walking the Wall, 2014, digital video. Purchased 2017. Te Papa (2017-0019-1/1-8 to 8-8)

Glossary:

aitu: spirit

au: traditional tatau instrument

fa’asāmoa: the Sāmoan way

malu: traditional Sāmoan women’s tatau

moana: ocean

pe’a: traditional Sāmoan men’s tatau

soa: tatau partner (pe’a and malu are usually done in pairs)

tatau: tattoo

tautua: service

tufuga ta tatau: master tattooist

vā: relational space