Taniwha in the Room: A Response to Speaking Surfaces, Part One

This is a story in two parts – a waning and a waxing – of Cassandra Barnett's attempt to complete an essay about Speaking Surfaces at St Paul St gallery over lockdown. Part One focuses on the major spatial installation in the gallery, VĀWĀ and a Creative Wānanga.

Hands

I am starting this with a vow: to start each day where I am, reaching hands to earth. We’re in Level 4 of our country’s Covid-19 response. I’m following Emalani Case who writes, the vā, the relational space, tells us that before looking out, before our eyes gaze across furrowed waters, we need to look down, reach down, turn hands down to the earth.

I have been planting seeds. I’ve been prepping the Wellington soil I’m gazing at out my window. I have been feeling this body, this person that I am too – how it feels to be Raukawa and Pākehā, urbanised, writing about the Moana phenomenon of vā from here, then there, then here. From my own between space. The whenua where I am now, where I garden, is in Ngaio. My tūrangawaewae are in the Waikato – and over the ocean. The year-long Speaking Surfaces project and ST PAUL St Gallery are in the rohe of Ngāti Whātua, in Tāmaki Makaurau, where I was raised.

As I write, the whenua beneath mekeeps changing. I’ll need to travel back before travelling forward again in this month of blurring days. I’ll need to write each day in its place. I need to trust that, like the wai within the earth, the stories of all these days can find each other. That like the earth itself they’re connected, and from them – from their temporary separation even – the vāwā of this story will ripple out.

Earth

I am reading about vā the week before my trip to Tāmaki, before lockdown. To think about vā at all I need Moana voices to help lay the ground. Sāmoan writer Caroline Sinavaiana-Gabbard tells me, In Samoan epistemology, the space between things is called the ʻvā.’ Relationships are vā, the space between I and thou. In friendship we cultivate the vā like a shared garden, that patch of ground between us we planted with bananas and strawberries. Teu le vā. Cultivate the space between us, our relationship ….1

Sāmoan writer Albert Wendt reminds me that vā is not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together … the space that is context, giving meaning to things.2 Already I begin to feel better about finding myself between so many whenua and peoples.

Tongan educator and poet Konai Helu Thaman says vā might also be thought of as a methodological foundation for peace and intercultural understanding ….3And this feels especially significant for the role vā plays (alongside the Māori wā) in this many-peopled project encompassing Māori, Aboriginal, Sāmoan and Pākehā creativity.

-- stand in a circle --

We are on Rangipuke outside the gallery entrance, in a space held by Jack Gray – who soon becomes our doctor, a healer, bringing medicine. He has two other dancers with him, Matiu and Abbie; and Charlotte from the gallery is here, and I’m here, and another friend of Jack’s is here with her daughter; due to the pandemic many participants have cancelled but we are here, fear or no fear, and behind us the automatic door opens and closes as we fidget – breathing for the building – and we’re breathing too, opening the space with karakia and waiata led by Matiu and Abbie and Jack, bringing in those who cannot be here because they’ve passed or they’re isolating or they’re distancing, and then, following our doctor’s orders, we begin

Second day of the Creative Wānanga with Jack Gray, Sunday 22 March at St Paul St Gallery

Tūpuna

I’m at home reading the Speaking Surfaces roomsheet the night before I fly. The central ‘speaking surface’ in the space will be VĀWĀ:a large, quasi-architectural, built structure filling much of the gallery space. VĀWĀ was designed by AUT Spatial Design graduate Sapati Mossiah Avei Fina’i, in response to a studio brief. The brief asked, How do we counter repeating established and institutionalised power relationships? Who, and what, is missing?

I don’t yet know what VĀWĀ looks like. I do know many additional students contributed to the project, and I’m happy to read the long list of their names from many places. It suggests that some of those ‘missing’ from our institutions were involved in this project, from the ground up. Online, I see VĀWĀ described as a platform for encounters.

I read that Speaking Surfaces also features video art, wall works and sculptures by six different artists/collectives. And that there’ll be a live wānanga activating the space over the weekend with tactile, multi-sensory events. The wānanga will be facilitated by Jack Gray (artistic director of Atamira Dance Company) with guest dancers Matiu Hamuera and Abbie Rogers, and sound from the artist Rachel Shearer.

Everything is too vivid right now and I can’t think straight. Everything is heightened. Like looking at the world after you’ve revived from a great sickness – but the sickness is yet to come. And I’ve never had a great sickness, so I don’t know if I can speak of that. Like I don’t know if I can speak of the film about the dog dreaming that I will see in the gallery tomorrow. Like I don’t know if I can speak of the vā. Like I don’t know if I can write of all the people, taonga, stories I’m about to see.

How do I speak of what isn’t mine? What is mine? If the virus enters my cells, is it mine? When does it become mine? I’m not sure what is mine, so I’m trying to just speak softly. Worrying at the tone of authority that haunts my written words, these inky shadows of architecture.

I remind myself these dreads are produced by colonisation: my dread of stumbling under the weight of mangled tikanga; my dread of square white spaces (pages, galleries); my dread of misrepresenting someone. I remind myself that it’s up to the vā, not me alone, to hold us together. I just need to humbly, wholeheartedly show up. Ready to receive and to give.

Ranginui

I am on the aeroplane. Tickling Ranginui, eyeballing impossible stars. Or should I say, Ranginui is tickling me. I’m reading Mouth Full of Blood by Toni Morrison, the only book in the airport bookshop I could stomach reading. I’m drinking water. I’m flying away from my seven-year-old, as pandemic fever swells and swirls, for a writing job. It is Ōtāne, a good day for fishing, eeling and crayfishing; a reasonable day for planting food. But toxicity is in the air. I am probably stupid to fly. But every job counts.

-- tell your pepeha --

-- speak your past, your future, your present --

-- draw it on the concrete with this chalk --

out come our maunga and awa, our homes physical and spiritual, thickly lined, dotted, smudged, like we’re kids again, and the pictures grow outwards and outwards until the doctor, going last, draws lines that reach further out from our tableau, down the steps, round the corner, to the north and east and south and west, invoking older tūpuna, Kupe and Te Wheke o Muturangi, and we have no spectators bar one labourer in high-vis who watches awhile, then enters our circle easily, saying, yes! what you’re doing! yes! this is what we need right now!, then goes about his business

Islands

I’m noticing the migratory birds. Noticing also the winds – how all those pollens and flowering plants landed up here, on Te-Riu-a-Māui, millennia ago. Even islands are clouded, dusted, swarmed, multiple, connected, tethered to the earth. They’re also watered, rained, streamed, sprung, rivered, estuaried, harboured, oceaned. And sometimes many islands are one continent. We’re separating, marking boundaries, but I feel so porous right now.

Like opportunistic pollen, the virus is approaching our border. In aerosols and droplets, determined, brave, ready to erode my fascisms, your fascisms, all the fascisms of our selves. It wants to live on in us, this virus. We sanitise. If the outlines demarcating our bodies are not thick, not permanent enough, we thicken them. We want to smell the spirit in the permanent marker, our sanitiser, till we’re high.

People are troubled. I’m fighting off cynicism and fear, because even in a pandemic the aesthetic of state control gives me the heebie-jeebies. I need to counteract that shit with acts of aesthetic of freedom, however small. When I get to the hotel I write out my feelings under the heading ‘Corona’. I’m refusing paranoia, but worrying about farflung whanaunga.

Toni Morrison wrote, in the context of post-9/11 nationalism, Porous borders are understood in some quarters to be areas of threat and certain chaos, and whether real or imagined, enforced separation is posited as the solution.

No person is an island.

Chalk, Creative Wānanga with Jack Gray, Saturday 21 March at St Paul St Gallery

-- breathe --

in a dish, the doctor lights the burner and the frankincense and the copal that Dubaian and Mayan friends have gifted him and when the smoke is roiling, nostrils instantaneously grateful, he places the burning resins in the middle of the chalk drawing

Rangipuke

I am standing outside ST PAUL St Gallery on Rangipuke, a maunga that’s not mine. It is Māuri, not a productive day – food is scarce, fish are restless.

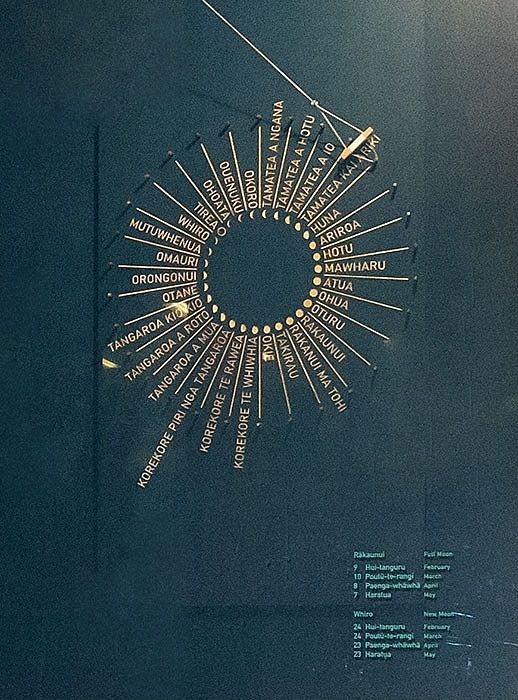

I am approaching the window space where the gallery faces the street: the round gold dial of a maramataka clockface pulls me in. Instead of numbers, the circle is divided into, and labeled with, the days of the moon. Against the black background it looks like one of those 70s starburst mirrors. Next to it, a slightly smaller, more cryptic sculpture sits riddling: What am I? It comprises two square wooden horizontal beds, one grounded, one hovering above, held aloft by thin strings. It is a three-dimensional diagram. The facing planes of the wood are contoured like an image of the earth’s crust in section. I know from the roomsheet that this is VĀWĀ in miniature. Like the words of the exhibition’s title, Speaking Surfaces, the two horizontal slabs pull and push. They quiz me: How are we connected?

Later I read that the planes’ contours do indeed echo the curves of the geological site beneath the gallery.

And from Jack I will learn that Rangipuke runs down to Point Britomart – whose Māori name Te Rerenga Ora Iti, loosely translated as ‘the leap of the survivors’ – marked the beginning of Ngāti Whātua occupation several hundred years ago.

I’m on Rangipuke, looking inward.

I’m waiting.

I’m waiting, like always.

I’m running, like always.

But we’re in no hurry. Take your time. Go in.

That’s what I think I hear.

VĀWĀ

The day is warm. The large side wall of the gallery doubles as a sliding door and it’s wide open. A porous border. There’s nothing between me and the room so I drift straight in, pulled towards the central installation: a giant version of the enigmatic sculpture in the window.

Big VĀWĀ is made of ply and is more friendly, more physically inviting, less conceptually challenging than mini VĀWĀ. Its top plane matches the rectangular shape and dimensions of the bottom platform, but hovers just beneath the ceiling and is rotated roughly 30°.

The bottom platform is like a stage. It is large and broad, and is perhaps 70cm high – an easy step up for me. It invites walking, moving around or sitting on, perhaps in a group, listening to stories and teachings. It is subtly chiseled with topographic designs. I don’t step up.

You’re welcome to get up there. Stand on it, sit on it,says Charlotte, dispensing with my perceptions of VĀWĀ’s surface as an atamira or other tapu platform. It’s a speaking surface, not a sacred surface. Noa, not tapu.

Cutting through the middle of both planes is the square concrete central support column of the gallery. VĀWĀ clearly evokes Rangi and Papa, making this poutokomanawa look like Tāne pushing them apart. Big VĀWĀ is fixed, but the window version is kinetic. The gallerists adjust it a little each day so it opens and closes in sync with the waxing and waning of the moon. The roomsheet confirms that VĀWĀ is here to broaden our attention to our location on planet Earth within the solar system,and to make us notice rhythms of life other than the Gregorian calendar’s dictation of a working day, week, month, year.

The roomsheet also reiterates what I’ve learned at many maramataka wānanga: that the days and months of the maramataka are told by tohu (signs) in our natural environment. The three key areas are tohu o te rangi(sky), tohu o te moana (water) and tohu o te whenua (land). The tohu are all connected and change as the year progresses.4

I have this much information, but still feel in the dark about what VĀWĀ is doing here.

Also, people are dying out there.

-- do your smudge dance --

and we dance, first Abbie, crawling, stalking, weaving, rocking, taut, receptive and sure over that wayward smoke; then Matiu, flexing and gliding in his yellow cloth of rippling tukutuku that flows with his hair with the billowing with the smoke; then the doctor’s friend who shed tears but now dances full-bodied and glorious with her seven-year-old, a magnificent dance partner; then me, awkward in my body but eager to scoop and spread, scoop and spread, scoop and spread that smoke; then Charlotte, baring her feet, receiving smoke from the soles upwards before picking up the dish and carrying it indoors, so we follow, and every artwork in the room receives smudge, and we circle vāwā selecting artworks to dance for, and finally they get to watch us, we commit ourselves properly to the work that is art that occurs between us, and the smoke lasts and lasts; it makes sure

Tohu

I’m in my bedroom in Ngaio, looking out at that tree, lockdown Level 3. It’s budding again, and tossing its leaves about. I am by our manga, Kaikomako, beneath our maunga, Kaukau. Whose name is really Kākā, really Tarikākā or Ōtarikākā – but you can’t snare kākā nowadays. It is Māwharu, a most favourable day for planting food,5 and I have planned for this. My soil is pungent with life and my seeds in their plastic pots have sprouted into keen seedlings, bustling to the call of the dirt. And the rain beats down, telling me it would have hammered the living daylight from those tender shoots anyway. They’re better off under the patio roof another night.

I’ve been on lockdown for five weeks with my high-octane seven-year-old. Solo parenting. Everything’s slowed down and my son consumes the lion’s share of my attention, my labour, my emotion. He’s small but he’s my lion in the room. So I’ve been unable to sit down and write. It starts to feel pressing. Not doing things – having to do them, yet not doing them – brings its own special, suffocating pressure.

I’ve gotta get out of here, I think. I rationalise it, tell myself, We’re overdue a walk, we’re behind on our exercise. Then I remember we walked for three and a half hours yesterday. Up Kaukau, along the ridge to the cellphone tower at its highest point. Getting buffeted by Tāwhirimātea, shouting to the Makara windmills and the quiet city, eating grapes from our pockets. We did Les Mills Body Combat on TV this morning. We went down to the stream, running across our lawn at lunchtime to play Pooh Sticks again and talk to Tīrairaka. Oh, I remember, We’ve done plenty. Why do I feel so jumpy – the way I hear runners get when they can’t go running? Oh,I remember. Because I’m trapped.

Covid-19 and its mediated entourage (the national flags, the patronising politician voices) are one elephant in my room. The writings I’ve promised in various directions are another. VĀWĀ is another. My son the lion is another. The room is pressingly full. I’m up against a wall in a tiny elephant crevice – psychically crouching, beneath a twitching belly.

What do elephants have to do with the vā? I’m very far from where I was. I’m reaching up through this rainy day, grasping at threads. Trying to get back there, to Tāmaki, to Rangipuke, where I have work to do. I remember I felt connection, joy, mischief. I wrote some words about it, even, under the heading ‘Medicine’.

Our stream is not really our stream. Our maunga is not really our maunga. Perhaps Māwharu’s not really Māwharu (refer to the tohu, not the app!). Maybe Covid-19 is helping VĀWĀ shift my attention. Slowing me down, giving me time to notice seasonal adjustments of earth, sea and sky. Insisting that I attend to every single day of the moon – a slowness I’m emulating by giving my text 30 ‘days’ too. Or maybe Covid-19 has infected our vā and everything’s awry.

I reach again for those threads.

Sapati Mossiah Avei Fina’i with Speaking Surfaces project team, VĀWĀ, 2020. Laminated Macrocarpa, Cotton string, plywood, steel (detail). Photo courtesy of artsdiary.co.nz.

Creatures

I’m back at my desk in my recently expanded Level 3 bubble. My boy has been collected by his pāpā. I’m pausing the screen-time negotiating, the drawing, the front yard goal-kicking and hoop-shooting. This weekend I’m writing. It’s Korekore te Whīwhīa, an unproductive night on the shore – winds sweep the sea. Too bad.

In my haunted imagination VĀWĀ has become increasingly creature-like. It crouches between me and the art, blocking my dive, my freeflow. I’ve seen the artworks – little portals I need to dive into – some patterned, some textured, some screened, some woven, some found. But VĀWĀ is crowding me, slowing me. Saying, Not so fast. Careful how you enter. No speaking until you’ve addressed me, engaged with me. This is our vā, not your flow-space. This unproductive night feels like a battle night.

I skirt VĀWĀ some more. It’s self-conscious but stubbornly itself. Coiled with a kind of life, an energy coming from its novelty and its surprising potential. As though it might next lick a paw.

Ok, I say. What?

But I’m projecting of course. Writing on the wrong day. Paranoia rippling out of my seven-week-long muffle-space, leaking out from virus-mind to cross-contaminate memory. The battle is with my paralysed lockdown state – and with our overweening State – not VĀWĀ.

How to claw my way back?

I return to my lifeline.

-- pour water and ink into your bowl --

-- let them evaporate as you walk --

in turn we fill a paper plate with a puddle of water and drops of metallic ink, turquoise, rust, singing as we go, waiata Māori, West African lullaby, it feels tika and Lori Esposito, an artist and friend of Jack's, who invented the evaporation walk, is with us, then we stand, each holding a plate in our two hands, and walk single file into the city, following the doctor, following the buried streams

we’re looking at our plates, we have one job to do and all others fade, so if people are turning their heads we don’t see them, and we’ve crossed Queen Street now and we’re heading into the bottom end of Myers Park, down the steps off Mayoral Drive with their wide middle strip of nonstick yellow; we are walking down this yellow stripe and all I see is my round bowl of green, the acrylic pigment twinkling a glittery sheen across its emerald surface, speaking oceans and chemicals and illness; all I see is my round green bowl against the yellow steps and all I feel are the micro-adjustments of my core as I step down while watching my bowl

Students

I’m reading the roomsheet again. While he was designing VĀWĀ, Fina’i asked himself, How can I create a space within the gallery to evoke one’s emotions, spirituality, thoughts and perspectives interpreting Vā? He interpreted the relationship between vā and wā as being interdependent.

Now I’m wondering if it’s safe to combine cultural concepts like this, wondering if I need to critique the mixing of cultures occurring in this porous exhibition space. Though I’m familiar with wā, I worry that I don’t have enough of a handle on vā to answer these questions. I haul books off my shelf, revisit an Oceanic literatures reading group on Facebook, charge around Google finding new readings on the vā.

I am reminded of the entwined whakapapa of vā and wā, and their ocean-like role of creating relations between ‘islands’. I counsel myself to let go of the Western-imperialist notion of space as a distance between us. Let the critical, analytical instincts go. Embrace more relational modes of resistance. Just feel what arises in this vā.

Sāmoan/Dutch educator Jacoba Matapo writes, The vā, as a relational sphere … becomes a conduit for story creation, storytelling and story reimagining. In education, the power of story connects teaching and learning … politics to power and the human to non-human life.

Fina’i says, I want people to … interpret what vā might mean for them.

I feel a teensy exhalation of relief. Like a permission has been given.

Evaporation walk, Creative Wānanga with Jack Gray, Saturday 21 March at St Paul St Gallery

Taniwha

I am numb. All thinking has subsided. I’m getting used to this silent companion sitting beyond my reach – beyond critique’s reach. Getting used to getting nowhere.

By taking up space, VĀWĀ is making me see something. I see how I expect a kind of emptiness or blankness of our institutional spaces. Nothing to see here. Just the artworks and a critical eye. I see how I’ve been trained to fit such spaces – to meet and echo the gallery’s emptiness with my own filtering mind. Now, like our planes, that state-sanctioned me is grounded.

Wendy S Walters has written that, in such institutional spaces, [b]lankness … [i]s at once the construction of emptiness and a complete fabrication … Blankness cannot exist in the material realm … The viewer's ability to perceive blankness depends on how much enthusiasm they put towards the practice of not seeing evidence of human, animal, astronomical or celestial presence.6

VĀWĀ conjures an institutional gallery space that is stubbornly not empty. Not neutral. Not blank. Not authoritarian. Not walled off. Not architectural. Not permanent. VĀWĀ is all clumsy, provisional, raw, friendly presence. As I surrender I hear it more clearly, saying, Come, no need of productivity today. I’m unsure, you can be too. Just be yourself, with all of us. Listen. Then speak.

And when I shuck off that blanking institutional gaze that had wormed its way inside me – and gotten amplified by a tyranny of distance, state-power aesthetics and paralysis – VĀWĀ laughs. Finally. Throws off the elephant suit and shows itself: a guardian taniwha. It was here all along, keeping the artworks company while I grappled. Holding space for them – and for me too. Drawing us all into its community.

-- remember --

in the park we stop and the doctor reads to us about this place in the ice age and about the taniwha Horotiu, who dwells in the stream that flows through here, first aboveground, now underground

Storytellers

It’s Saturday morning, Māuri, and Jack is just arriving, shiny black bag in hand. He’s not really a doctor. But he’s definitely a time-traveler. As I approach to mihi I remember the last time we met, six years ago. I notice how it’s him but he’s older, gentler, softer, and how his hair has grown long and changed colour: it’s both grey and flaming. But I’m older too so who knows who’s changed. We greet across the socially-distant metres and laugh and chat awhile, then I turn back to the art. Next time I glance his way he has magicked out a cloth and is laying down his shrine.

In a conversation with architect, poet and artist Elisapeta Heta in the book Unfolding Kaitiakitanga,Jack says, When Māori perform, our energy actually goes out to mihi to everything … I think Māori curate energy differently, it is a way of informing others, showing we are also completely connected to them ….7 And Heta makes a comment in beautiful counterpoint to Walters: [in te ao Maori] the notion of neutrality doesn’t actually exist at all because everything we do leaves marks on a place. The wairua or mauri of our kōrero, our waiata, those things, they literally mark spaces.8

VĀWĀ is a stage, a space for relating and healing, a speaking surface, a platform for the story to unfold. Jack will be our doctor, our storyteller. When he arrives he ushers in a new resonance for every work in the room.

I feel this resonance when he lays out his shrine. His ramshackle collection of talismans echoes the more polished, rarefied ones I’ve noticed scattered down one end of VĀWA – but not looked at closely yet. These two treasure collections resonate in a way that resonates in turn with the video works on the adjacent wall. Again, I’ve not looked closely at them yet, but I’ve noticed their loose shifting visual overlay of filters: sepia and three-colour separation effects. Everywhere I feel that and this. The distant and precious and the alive and fresh. Looping and dancing back through time to carry the distant forward into the freshness of now again, and the now back to before.

This kind of energetic movement needs people. Live activation from our energies pouring in, through, onwards … Our hands and eyes and ears and noses and tongues participating. I begin to understand that, though I came for art and writing, I’m really here for ceremony.

Myers Park, Creative Wānanga with Jack Gray, Saturday 21 March at St Paul St Gallery

Waihorotiu

I am in the furrows of Waihorotiu. The Tāmaki stream, with its taniwha Horotiu. It is Orongonui, a very productive day for planting food, fishing and eeling. Of course, Waihorotiu doesn’t age. But the tohu of Waihorotiu here now – these green-edged gullies of grasses, sliding by tree-root and concrete in the low slopes of Myers Park then Queen Street – evoke a Waihorotiu past, a way she ran when her running was wet and open-skied. With her slippery, language-fluid ways, she whispers precocious things in my ear. They push up through the culverting earth to greet me.

What took you so long?

Waihorotiu’s been waiting.

But such voices can be dangerous in print. Save such voices for the vā.

-- with a partner find a place where the buried waters sing to you --

-- dance with them --

and I dance in my way with the doctor dancing in his way; I want gravity to suck me, hold me; my body sinks, becoming earth, becoming taniwha, becoming water

Air

I am breathing again. Covid’s still in the air, but something’s changed. I turn off the TV, forget about Aunty Cindy, forget about the fear and obedience they need from me. Remember my way back to the ceremony. And from there, back to the art.

Art

Finally, I can see the art.

-- here are your felt pens --

-- freewrite --

and we write on the butcher paper spread across VĀWĀ, and Rangi and Papa and all the artworks are not audience but witnesses, collaborators, whanaunga; we come to practise, we come to surrender, we come to heal

then Māuri turns to Orongonui and we are back in our circle starting over: nguru, karakia, waiata

Speaking Surfaces

St Paul St

28 Feb 2020 - 16 Oct 2020

Feature image (top of page): Sapati Mossiah Avei Fina’i with Speaking Surfaces project team, VĀWĀ, 2020. Photo: Sam Hartnett. All images courtesy of St Paul St unless otherwise stated.

1 From the Introduction to her collection of poems, Alchemies of Distance (2001), 20.

2 From “Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body,” Span 42–43 (April–October 1996): 15–29 (and quoted in the Speaking Surfaces roomsheet).

3 2004, 32, quoted by Spaley, cited in Kaʻili 2008, 23.

4 Ayla Hoeta, “Learning to Live by the Maramataka: Aponga,” The Spinoff, August 7, 2018, (referenced in the Speaking Surfaces roomsheet)

5 Maramataka days here are taken from the smartphone app Hina. The app’s accuracy depends on the user’s geographical and temporal location; but since I myself have been moving around, the difficulty of gaining a true reading is part of this story.

6 “White-Leader,” Full Bleed, April 4, 2017.

7 Unfolding Kaitiakitanga,eds., AbbyCunnane, Elisapeta Heta, Charlotte Huddleston, Martin Awa Clarke Langdon (Tāmaki Makaurau, Aotearoa: ST PAUL St Publishing, 2016), 72. The book is linked with another ST PAUL St Gallery project (Since 1984, 2014).

8 Ibid, 68.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with St Paul St gallery, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.