The History Beneath the Concrete: Talking about Pōneke with Ruby Solly

"The deeper you go into your whakapapa, the easier it is to connect with all things” – musician Ruby Solly in conversation with Kahu Kutia, on the release of Ruby's album Pōneke.

In the years to come, we will talk about the rising tide of urban Māori who are owning and affirming their identities like never before. We stand on the shoulders of the waves that rose before us, those wayfinders who dared to enter the city when it was a cold castle slapped on native land, consuming all our own who dared to enter. The brave back then were Ngā Tamatoa, the Ranginui Walkers, Carmen Rupes and Bruce Stewarts. They were the gangs and workers, our aunties and uncles, nannies and koros.

Now they’re us, and the city is a different place to the one those first urban Māori came to. There’s a historical legacy that labels urban Māori as lost and disconnected from our culture. What I see are waves of urban Māori affirming their identities in ways that build on tradition and take it to a place that, although new, is unapologetically Māori.

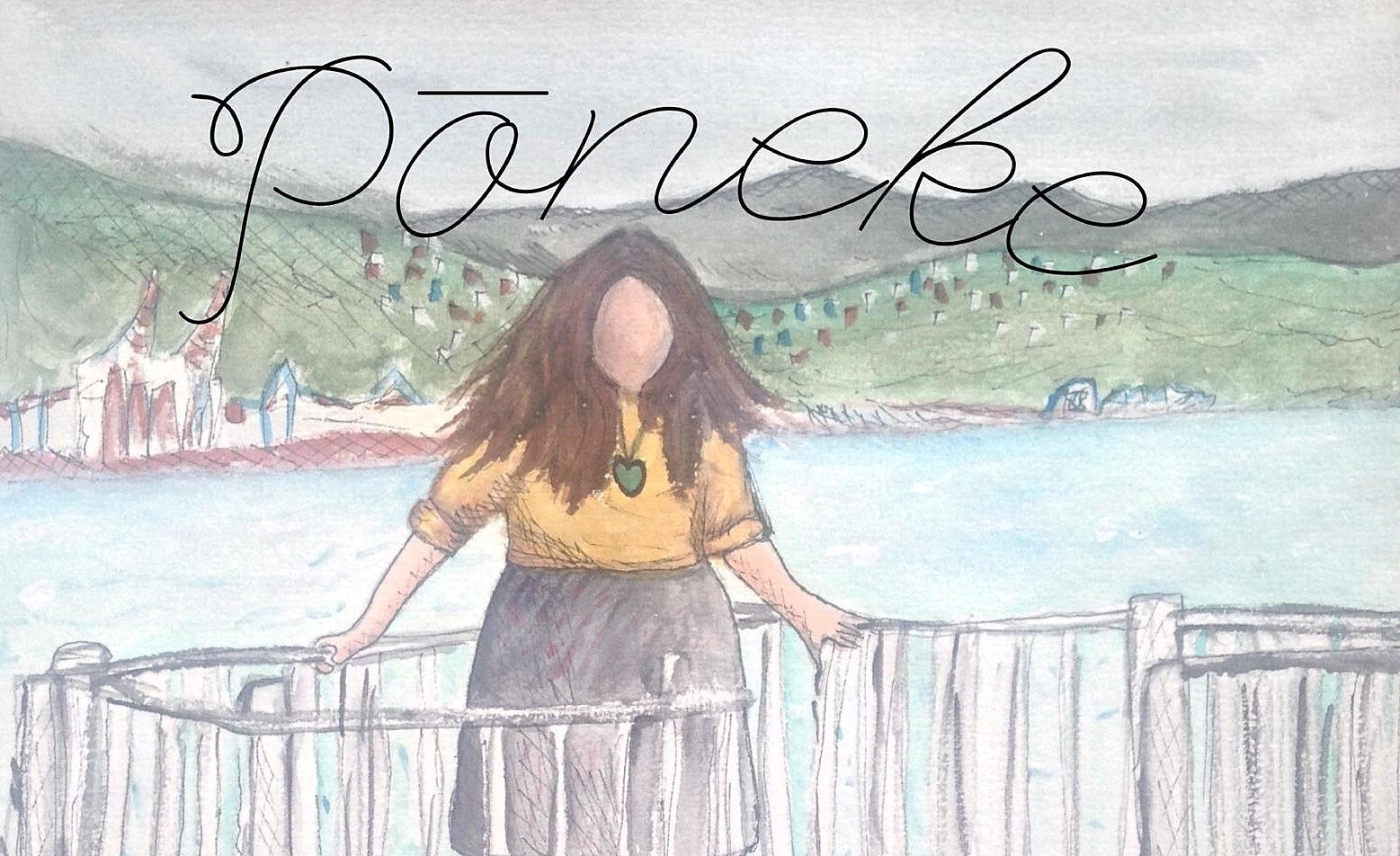

This article is a kind of review, and a kind of discussion (because single-voice reviews are colonial af anyway) of Ruby Solly’s (Kāi Tahu) new album Pōneke, to be released on 5 June. Pōneke is an album that interweaves the sounds of cello and ngā taonga pūoro in direct conversation with different locations around Pōneke Wellington. While the album is the central component, it includes a book of art and poetry by Ruby and video content made in collaboration with Sebastian Lowe and Viktor Baskin from Otis Makers.

You might know Ruby for her beautiful poetry, her work as a music therapist, the taonga pūoro she plays, or even her delicious Belgium biscuit recipe. I met Ruby last year when she interviewed me about my podcast, He Kākano Ahau. In the tail-end of a national lockdown, we organised a zui to discuss Pōneke.

Kahu Kutia: I would really like to start by saying what a privilege it was to read, listen to and watch this project. There are all these different layers to Pōneke and I loved every single one of them so much. Your artwork and poetry really allowed me to get a deeper sense of the soundscapes you create in this album. And even in the way you blend non-Māori instruments with taonga pūoro. I can see the foundations of the work done by the likes of Hirini Melbourne, but it moves in such a different direction. I really do get a sense of what you perceive in these different city locations, and to listen to the album and feel that I am there with you in these places is an incredible experience.

Learning to be in tune with te taiao is something I’ve been exploring during lockdown. Of course this album is so tied to physical location and to places of significance in the city of Pōneke. We spend a lot of time talking about how the whenua and taiao speak to us through tohu in the sky, or through a pīwakawaka coming for a visit, or something like that. But what it feels like you’re doing here, and what I love, is the feeling that this project is about learning how to talk to te taiao. It’s so relational and such a direct response to this city that you and I live in. Does that ring true for you?

Image: Sebastian J Lowe

Ruby Solly: One hundred percent and thank you for those comments. When I started this project it was me just exploring these ideas and spaces. After I’d created a few of these tracks and learnt about the history of these places, I realised that maybe it was something bigger.

On being in conversation with the taiao, this is really important. Last year, while working on a joint project called Resoursonance with Liam Prince from The Rubbish Trip, I remember us talking about the environment as a place we go to to enjoy, instead of something that we are in communion with.

So that was the idea that I wanted to explore, but it wasn’t me being like “Right! I’m gonna go out there and have a conversation.” I like to think of talking with te taiao as something that is natural, like how you meet someone and then just start talking to them.

KK: Maybe two weeks prior to listening to Pōneke, I got the chance to interview Dr Rangi Matamua and we talked about what it means to converse with the environment. I’m still learning to interpret tohu from the world around me, but I think I know less about talking back. Then suddenly Pōneke came to my eyes and ears and, after that conversation, what you were doing made so much sense to me. Did you come to this understanding while creating Pōneke or did it come from the world of taonga pūoro? Or is it something you’ve always done?

RS: I think it definitely comes from taonga pūoro. For me as an adult, that’s where it comes from. But then I think back to a point in my life before people started directing my music in more academic spheres. Back then, it was natural for me to communicate with the environment. In the tradition of taonga pūoro, we learn from other players by listening to them and learning from them. But, equally, we also learn from the environment. I think that way of conversing with the environment is something that taonga pūoro artists really have to offer as a philosophy to the wider music world and in the way that people think about their interactions with te taiao in general.

Image: Ruby Solly

KK: As I said in the beginning, what’s so amazing about this work is how relational it is to these places that you converse with. In the track “Somes” there's a palpable air of grief, and melodies that remind me of the tangi of a kuia. This makes so much sense to me as I think back on an adventure I took to Somes one time and the deep sadness I felt when exploring the quarantine buildings. You’re telling stories about all these places in our city that would otherwise be unseen. The city can sometimes feel hostile, especially if we are trying to grasp a pre-colonial landscape. Was there anything about being in these spaces that was confronting to you while creating Pōneke?

RS: I had to be aware of the sounds that I wanted to capture as opposed to the ones that were there. I’d go into some spaces expecting them to sound a certain way and they wouldn’t. At the start of the project I’d be like, I want the sound of this place to be full of cars or full of birds, but then I had to look at the whakapapa of that sound and how certain sounds had come to be in certain environments.

KK: So cool.

RS: Some of the material in history books was quite confronting and I think this is reflected in the project. It was confronting because it prioritised a colonial history of the land instead of a Māori one. I went on a hīkoi with Tipene O’Regan and some whānau from Kāi Tahu, and we learnt about Kāti Māmoe, who were here. This was interwoven with kōrero about Kai Tara and Kāti Ira, and how they worked together with Taranaki Whānui and Te Ātiawa as well. In some way I feel you can hear all of that kōrero in these tracks. I think that is why Pōneke can feel quite heavy at times. For that reason my favourite tracks on the album are the ones on Karaka Bay. The stories that are woven in those tracks relate to the kōrero I learnt with Tā Tipene.

KK: I must say, those tracks are my favourite too.

RS: Yeah! It was a comfort thing, too, because this is a part of my history that I know well and feel quite deeply. These people were here and I’ve even got physical artefacts that I can touch. It’s kind of the closest you can be to feeling like you’re from somewhere, because the people you’re from planted those trees.

Image: Sebastian J Lowe

KK: One thing I am reminded of is kaumātua visiting other marae, and when they get there they start off by weaving their whakapapa in with that place. It feels like Pōneke is another incarnation of that tikanga, you know? Like you’ve somehow woven the early whakapapa that you have with this place and the stories of your ancestors into this album.

RS: I decided a while ago that if I was gonna be working on a personal project, it had to be something that was gonna grow me as a person. Pōneke has really done that. I know now that I live on an old rīwai plantation that is connected to me through whakapapa. I know we can go out to Karaka Bay and climb the trees my tūpuna planted. There’s a whole lot of things I can do to help me affirm my whakapapa, even though I’m here in Pōneke and even though I’m Kāi Tahu. That’s really beautiful to me.

The deeper you go into your whakapapa, the easier it is to connect with all things. Sometimes I think that if no one is into Pōneke, I’ll be okay because I’ve learnt so much about myself and I feel like I’ve become a stronger musician. I value te taiao more and I’ve become more used to conversing with our atua. It feels like I know myself better, and all the layers that make up the self that I am.

KK: Well honestly e hoa, e mihi ana. This work for me is not only something that allows you to grow, but it holds such powerful space for anyone consuming the project to also grow and learn. That’s certainly been the case for me.

Pōneke is available on Bandcamp (June 2020)