Takatāpui Superpowers

Taualofa Totua on activist artist Kahu Kutia, and the whakapapa of her work Te Pō in Te Tīmatanga Auckland Pride art trail.

I first met Kahu Kutia on 27 September 2019 in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, on the steps of Parliament. She was there with Indigenous climate-change group Te Ara Whatu, and I was there with the Pacific Climate Warriors of Wellington. It was moments after I finished speaking to the 40,000-strong crowd gathered outside the Beehive, spilling out past Parliament’s gates, and onto Molesworth Street, stretching to the edges of Lambton Quay. Everyone there that day was protesting against climate injustice, and for a better future. At the bottom of the steps, the elderly and less mobile were seated on fold-out chairs as pre-schoolers clutched drink bottles, and school bags settled on the concrete close by. Beyond them were the more passionate kids of Wellington who had wrestled their way to the front of the march, mingling with older, sophisticated uni students who had ditched their classes, too. All were in their ‘activist’ gear: smart slogans self-printed onto thrift-shop clothing, bright cultural dress paired with flags, and articulate cardboard messaging, calling for immediate climate action. The protest was peaceful and intergenerational, the scenes an encouraging memory of communities coming together for future and present generations, compared to the recent ‘Freedom’ protests at Parliament.

Kahu Kutia was wearing her ‘activist’ clothing too, sporting a painted-statement tee: ‘Indigenous lands, Indigenous waters, DESTROYED and no one is being held to account’. Speaker, occupier, editor, journalist, delegate, protestor: just some of the labels that Kahu carried that day outside the Beehive. Since then she’s added podcast host, director, event producer and, most recently, artist to the list. More than two years on, I asked Kahu to talk about her latest work, Te Pō / when we were erased we came back here, part of Te Tīmatanga Auckland Pride art trail throughout Britomart, in downtown Tāmaki Makaurau, and discovered more reasons why this takatāpui wahine Māori deserves our respect.

Image credit: Melody Thomas

We met on Zoom as the shortest month of the year came to a close. We were both in isolation, discussing the reality of being confined to a room for 10 days – but grateful nonetheless. I’m reminded of how a mutual once described Kahu as “mean to yarn with”. With a lineage to Ngāi Tūhoe and a childhood in the Eastern Bay of Plenty in Waimana, Kahu is quiet and thoughtful when asked: how would you introduce yourself to your ancestors? “What a cool question! Well, my hope is that they would already know who I am and I think in a lot of ways they do. I feel them a lot in my mahi and my everyday journey. I’d probably introduce myself to them by talking about my intentions for being in the world and what I want to do as an ancestor.” At 25 years old, Kahu is already working on being the best ancestor she can be.

A month after the 2019 climate strikes, she launched the six-part first series, Urban and Māori, of the award-winning podcast He Kākano Ahau, for RNZ. Inspired by her own experiences of moving from Te Urewera to Wellington to study in 2015, Kahu discovered “what connects us as Māori in the city”, meeting with other urbanised Māori in Tāmaki Makaurau, Te Whanganui-a-Tara and Ōtautahi. This was followed by a successful second series last year, Wawatatia, targeting young Māori with “conversations that help us radically reimagine how the future might look.” Kahu’s writing and journalism mirror her wide involvement in her communities, spanning a range of genres and formats. She was the editor of the annual Māori student media publication at Te Herenga Waka, Te Ao Mārama, in 2017, before being published on various platforms; from here at The Pantograph Punch, to Vice New Zealand, The Wireless and Theatreview, to name a few. Their most recent written work, ‘i will live and die a thousand times and still be of this land’, responds to the Tūhoe concept of matemateāone, and is published by Māori researchers Kauae Raro Research Collective. Kahu acknowledges Sarah Hudson from the collective as an early artistic mentor and instigator for her growth. “She really encouraged me to share my work from that early point, to share my ‘artwork’ and call it ‘art’, the same art you’d traditionally see in an exhibition space. She also asked me to be part of the Mana Whenua book, in which she sent a whole range of pigments to different artists to work with”.

Kahu took her first steps to radicalisation against colonial systems when police raided Tūhoe in 2007

Kahu took her first steps to radicalisation against colonial systems when police raided Tūhoe in 2007 and accused the locals of running suspected terrorist training camps. From a young age, firm in the knowledge of her whānau, Kahu learned the injustice that the history of Tangata Whenua tells us. Her life of daily resistance and reclamation began. A short stalk of Kahu’s Instagram confirms the wahine’s adventurous and energetic indigeneity, which has blossomed since living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Working alongside grassroots organisations and takatāpui Māori networks, Kahu’s artistic identity has developed too: “I really feel that I could not be an artist if I didn't live and consume other artists, specifically Māori artists and also artists of colour in Aotearoa… If I didn’t live in this community, I don’t think I could create at all.”

Kahu traces her current artistic endeavours back to her early climate-justice mahi, which she acknowledges as the trigger for the creative mahi she does now. In 2018, Kahu completed her Bachelor of Arts, paying “$30,000 to receive a history of Aotearoa that I should have received in high school, and to take back the reo that shouldn't have been withheld from me in the first place”. That same year, Kahu joined six other Māori and Pacific rangatahi, forming the environmental group Te Ara Whatu and attending COP24 in Poland. The visit was funded in part by the sale of Kahu’s prints. Kahu wanted to create more, dabbling in various mediums during the first lockdown before turning to social media to share the outcomes. “I made an art Instagram account because I didn’t want my normal feed to be disrupted,” she laughs. “Then I started posting, and everyone liked it, and I was like… What?!”

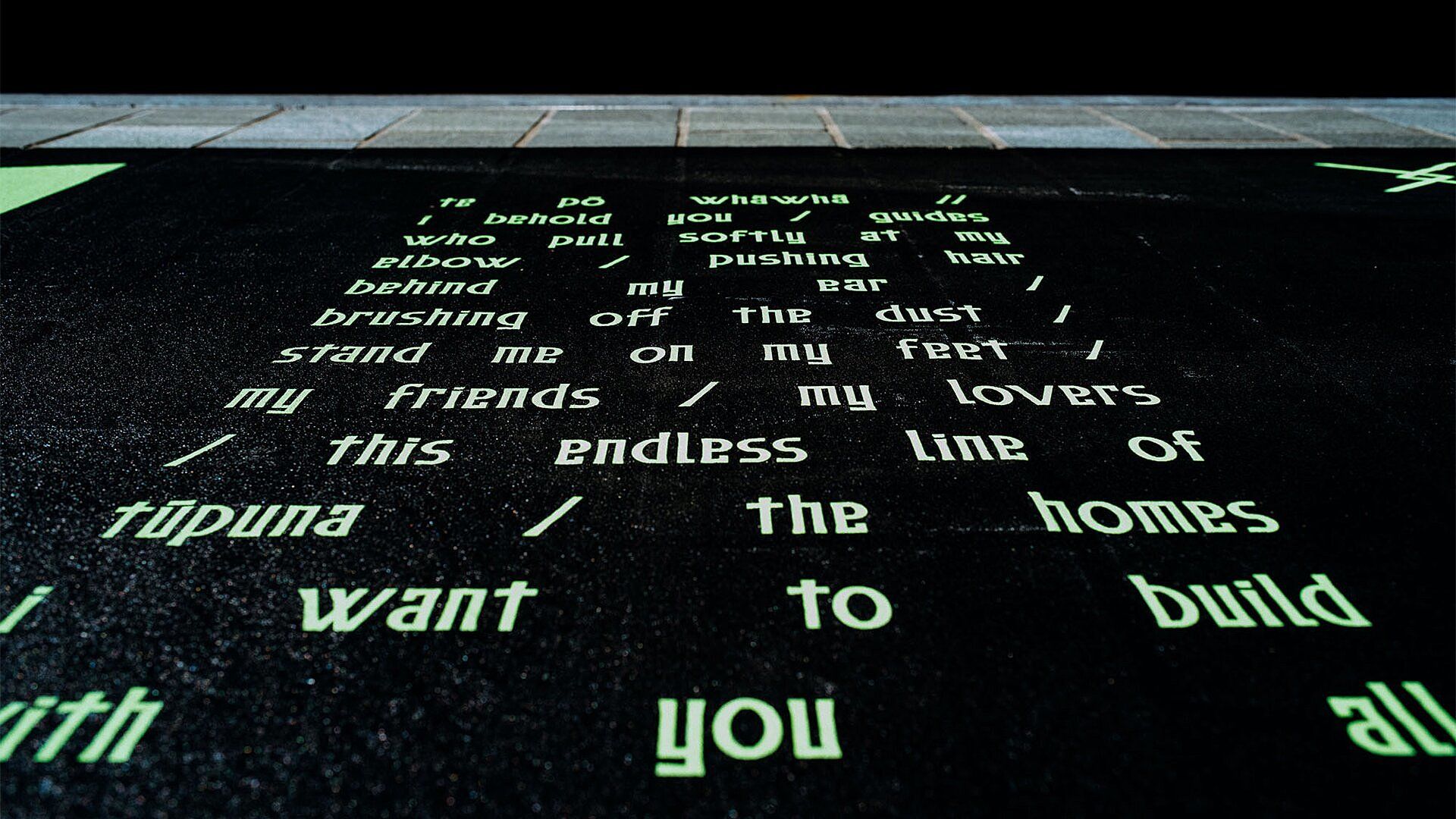

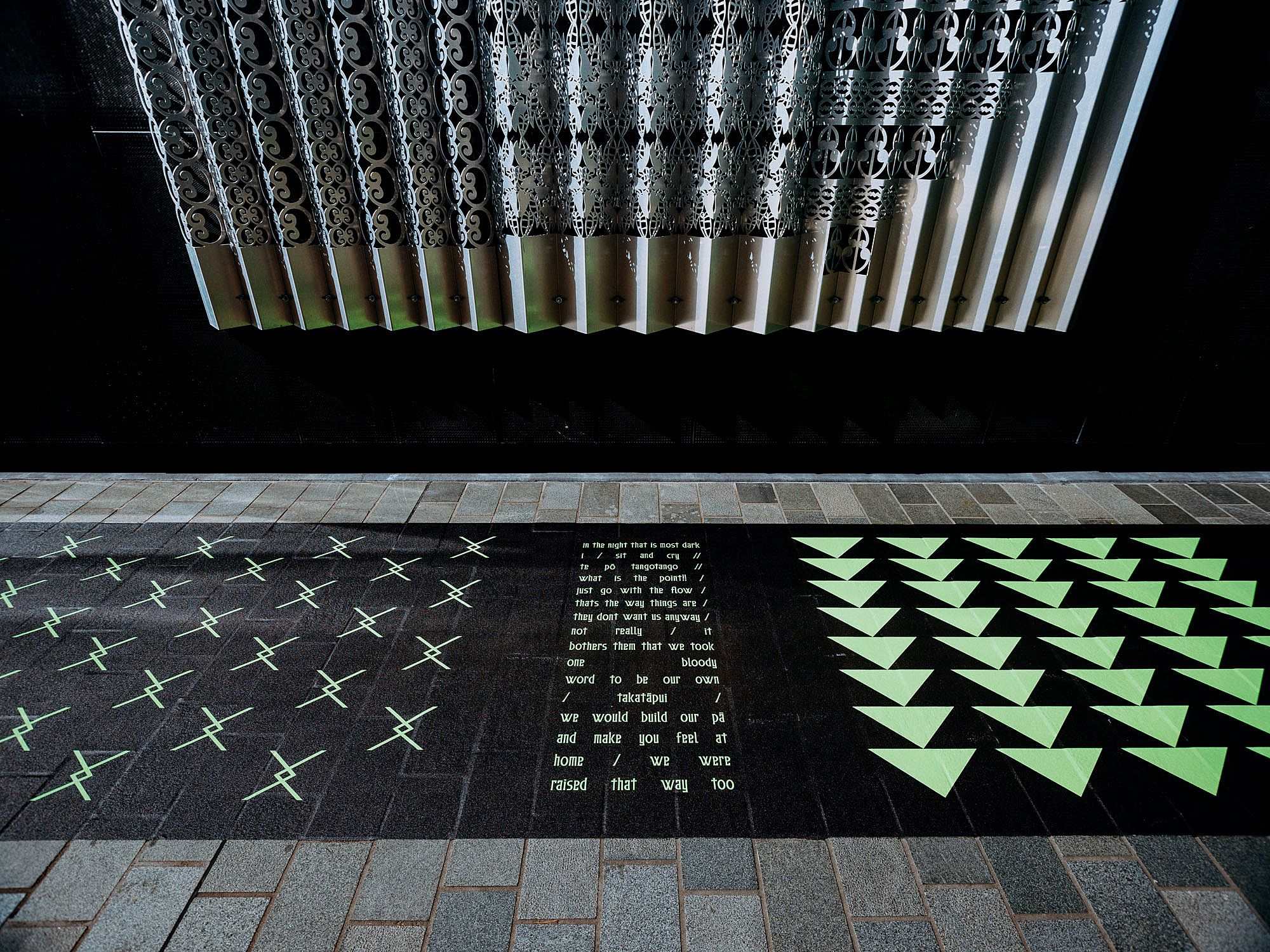

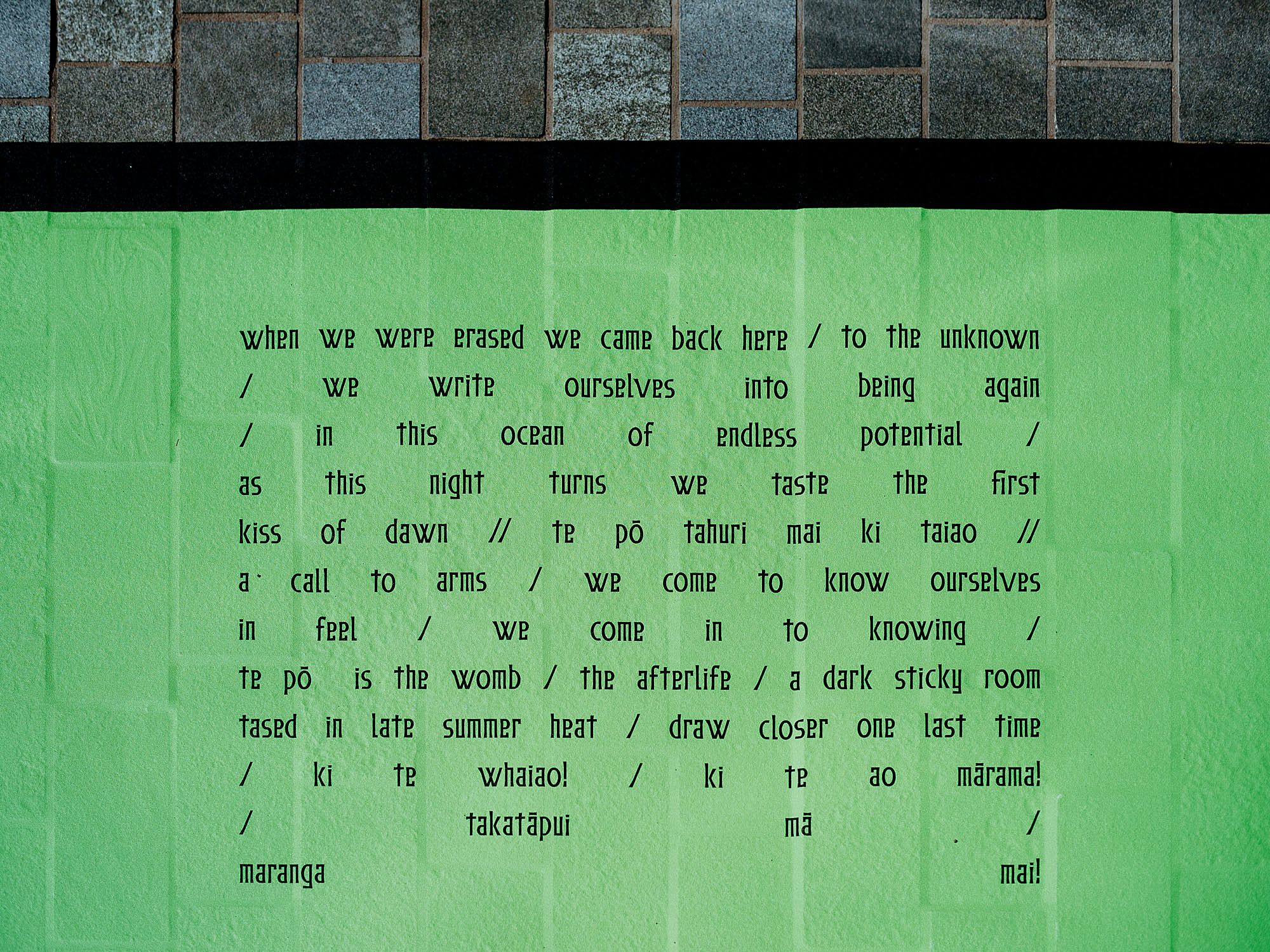

Kahu Kutia, Te Pō / when we were erased we came back here, Te Tīmatanga Auckland Pride art trail. Photos: David St George

Like many artists, Kahu was filled with doubt about sharing her work publicly. But this stage of her career has been 25 years in the making. The cupboards in Kahu’s childhood whāre were packed with paints and paintbrushes, yet her Year 9 and 10 art teachers suggested that she couldn’t actually paint very well. From then on, Kahu never considered visual arts, instead choosing photography in senior classes at high school. ‘Visual artist’ is still an uncomfortable label, an awkward fit, for reasons Kahu says are silly, and that she doesn’t share, but likely stem from the traditional eurocentric definitions of what art ‘should’ be.

Kahu highlights the landscape in which Te Pō sits, emphasising the relationship with other works in the exhibition itself but also the privilege of sharing space with other more-established Māori artists, such as Lonnie Hutchinson, whose work is above hers, on the street. Shane Cotton’s work is around the corner. Being aware of the environment of Britomart – a space that is foreign to Kahu but loved by “really wealthy, really privileged” groups – was key for Kahu in “setting intentions” before starting the design. “There’s all these fancy stores there that I would never go into”. Creating for an unfamiliar space caused some conflict for Kahu, knowing that thousands would walk past a piece of her “heart-and-soul work” without a second thought.

“We as takatāpui have had to go to Te Po to ask ourselves what it means to truly authentically be ourselves in all the senses”

Kahu Kutia, Te Pō / when we were erased we came back here, Te Tīmatanga Auckland Pride art trail

Kahu resolved that conflict by focusing on the positives: it’s a success even if it gives only one person amongst the thousands grounding in their takatāpui identity. “We as takatāpui have had to go to Te Po to ask ourselves what it means to truly authentically be ourselves in all the senses.” A large-scale, highly visible exhibition for the takatāpui community excites Kahu, who has claimed the label ‘takatāpui’ only in the last three years. “Even earlier on in my journey, I didn't really see it as a label that I felt I could have any claim to, which is not the case. All takatāpui have a right to their takatāpui identity.”

Talented Māori peers were another reason Kahu wanted to be a part of the project, noting Hāmiora Bailey (Ngāti Porou ki Harataunga, Ngāti Huarere) as a personal favourite to work with in creating accessible art. It’s another plus that the art is not locked away in a gallery, but outside where people can interact with it in real time. “I'm such a fan of literally every single artist in this exhibition… I really like the idea that people can go up and touch it and really be with it.”

Kahu Kutia, Te Pō / when we were erased we came back here, Te Tīmatanga Auckland Pride art trail

"Just by existing we have to rewrite what it means to be Māori for us, rewrite what it means to exist in the world. That, in itself, is a superpower”

The exhibition Te Tīmatanga is structured along the whakapapa within te ao Māori about the origins of the world. Challenging the erasure of takatāpui is embedded in the work Te Pō,which is the end of the transition period. “We have never, ever been seen in our historical records; nor quoted in our kōrero tuku iho are all the stories that came before us. Just by existing we have to rewrite what it means to be Māori for us, rewrite what it means to exist in the world. That, in itself, is a superpower of creation and reinvention”.

Kahu illustrates the 12 phases of Te Po in 40 metres, a contrast to the artist’s prints, which are usually A4 or A3 sized. Launched in celebration of Pride Month, the work laid out on the footpath of Galway Street is of the 12 dark nights that occurred during the birth of the world; weaving elements of poetry and whāriki in a “contemporary remix style that I made on Photoshop”.

Kahu Kutia’s Te Pō / when we were erased we came back here embodies the takatāpui superpowers she willingly gifts Tāmaki Makaurau CBD. The city is all the better for it.

Kahu Kutia is studying for a Master of Creative Writing at Victoria University’s Institute of Modern Letters in 2022. You can view more of Kahu’s mahi here.

Feature image: David St George

*

Taualofa Totua is a cadet in the Next Page cadetship programme, public interest journalism funded through NZ On Air.