Hey, You There! Tactics of Refusal in the Work of Luke Willis Thompson

Intentions and tactics, K Emma Ng considers the testing work of Luke Willis Thompson.

Intentions and tactics, K Emma Ng considers the testing work of Luke Willis Thompson.

Luke Willis Thompson does not give slick answers. Following his talks, question time tends to run long and late, mostly because Thompson spins elusive, drawn-out replies. Listening to a recent recording of him in conversation with curator Polly Staple at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, there’s palpable tension as Staple pushes Thompson along, struggling to keep the event running to time. More than once she has to nudge him to do some audience handholding – probing him for a backstory or insight to what they’ve discussed while developing autoportrait, his latest work.

At times, Thompson seems to be weighing up whether or not he wants to reveal pertinent details about the work. It’s not that he doesn’t have answers – he’s clearly thought meticulously about every decision he’s made – he just doesn’t seem to want to give up an easy answer. I suspect this is, on Thompson’s part, a tactic, in the same way that the French philosopher Michel de Certeau used the word “tactic”, to describe everyday acts of adaptive resistance to “strategic” exertions of institutional power (e.g. taking a shortcut in spite of the City grid).[1] Refusal is part of the way Thompson constructs himself as an artist. There are many frames that could be applied to Thompson’s work, but it’s this one in particular and a pattern of other related themes – exertion and resistance, trauma and restoration, the institution and the individual – that ripple through his work from the inside, out.

For an artist in his late-twenties, Luke Willis Thompson’s dance card is pretty full. Since graduating from Elam with an MFA in 2010, Thompson has won the Walters Prize; made work for the New Museum Triennial in New York, graduated from Frankfurt’s Städelschule; been included in the São Paulo Art Bienal, the Asia Pacific Triennial and the Biennale de Montreal; plus had a survey of his work staged at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane. Most recently, he’s been living in London as the 2016-17 recipient of the Chisenhale Gallery Create Residency.

Critic Anthony Byrt describes Thompson’s works as “connected by trauma, place and memory” and these concerns are always skewered by questions of race and class. Thompson has exhibited found objects (some bought, some borrowed), set up trips for the audience to take (departing from the gallery by taxi or on the trail of a performer), and made photographic works (including films). He’s interested in the objects and images that emerge from conditions of trauma, as well as the limits of the artwork: the point at which these objects and images can become art, and then perhaps exit again, to function in the “real world” once more.

He’s interested in the objects and images that emerge from conditions of trauma, as well as the limits of the artwork: the point at which these objects and images can become art, and then perhaps exit again, to function in the “real world” once more.

Sometimes Thompson’s work is autobiographical, but less in the sense that it’s is about the artist’s life and more that these are just the terms of its existence. Accordingly, Thompson can be detached when addressing these aspects, as if all that needs to be known is implicit in the work. For example, inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam (2012, 2014), delivered the audience to a house in Epsom, Auckland, and allowed them to look around – without divulging that the house was the artist’s family home, from which his mother had to depart each day, in order for the work to take place. Thompson himself has likened his work to a Rorschach test, asking of this one in particular, “What does it say about the reviewer, if they’ve chosen to read the work as a portrait of poverty and gentrification rather than one of maternal love?”[2]’

Since his relocation to the Northern Hemisphere, Thompson’s interests have shifted with him, and recent works centre on the experiences of African American and Black British subjects. Ethical questions have always emerged from his practice, but now chief among them is: what are we to make of him working with Black trauma? As well as testing the limits of the artwork, Thompson is engaged in testing how far solidarity between people of colour can go, the claim of authorship upon work that explores the experiences of others, the privilege of the artist to enter and exit particular terrain at their own will, and their opportunity to capitalise on others’ trauma.

Ethical questions have always emerged from his practice, but now chief among them is: what are we to make of him working with Black trauma?

Thompson himself rarely seems to attempt to smooth down the difficulty of these issues, as evidenced in his response to questions at the Chisenhale. One audience member, in framing her query about autoportrait, said: “for me, this is not an ethical question as this work is made by two consenting adults…” (meaning that the subject, Diamond Reynolds, had been a consenting and engaged collaborator in the production of the work). In his reply Thompson asserted that he did in fact think it might be an ethical question nonetheless. Another audience member supposedly asked, “how do you check your white privilege?”, to which Thompson replied “I don’t have an answer for that”. Yet elsewhere Thompson has attempted to bridge the question of solidarity, speaking to Anthony Byrt of the parallels between Caribbean migration to the United Kingdom and Pacific migration to New Zealand (a trajectory that brought parts of Thompson’s own family to Aotearoa).

This ambivalence suggests a somewhat conscious engagement with the complexities and contradictions inherent in his practice, and with the ethical questions stirred up by his work. But it also makes evident the extent to which Thompson attempts to negotiate his own terms of engagement.

THE DESPERATE DOCUMENT

August is torrid in New York City; riot weather. On a recent August night, my friend Ted and I went along to a screening of Thompson’s Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (2015), at the Swiss Institute in Soho. This work consists of two 16mm film reels, each a single take of a young man descended from someone killed by London’s Metropolitan Police. Brandon’s grandmother, Cherry Groce was shot in 1985, triggering the Brixton riots. She died of complications from her injuries in 2011. Graeme’s mother, Joy Gardner, was killed in her home in 1993, as police tried to detain her for deportation.

The projector whirrs throughout the silent films; five-minutes for Brandon, five for Graeme. Projected larger-than-life, the young men’s faces are tightly framed; the camera static, as they stare down the barrel. I don’t wish to get carried away fetishising the analogue qualities of the medium, but it is worth noting that there’s a remarkable liveness to the work – a silver crackling that makes one willing to go along with Thompson when he later suggests there’s some element of metaphysical elision that occurs in the imaging of these bodies on film.[3]

On this occasion, the work was screened twice, with an artist talk sandwiched in-between. Thompson framed the work as a response to the images of Cherry Groce and Joy Gardner that circulated widely in the wake of their victimisation. Those images, which defined their lives in the public eye, continue to be reproduced in the media on the anniversaries of the events. By contrast, the distribution of Thompson’s work is tightly controlled; the film is only shown when Thompson accompanies it, and because of its analogue nature is dependent on the availability of projection equipment and cannot easily be reproduced.

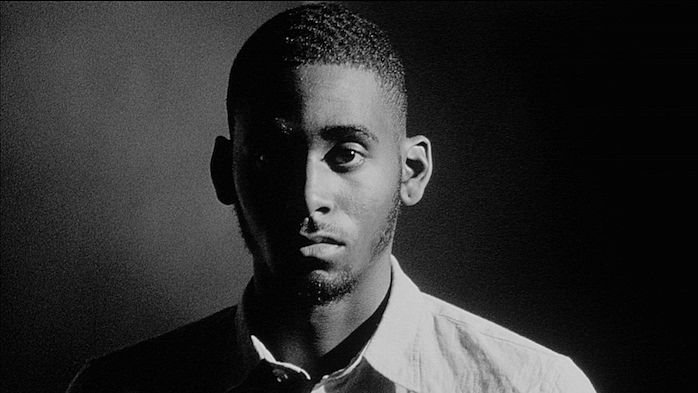

It’s with similar intent that Thompson describes autoportrait, his most recent work, as a “sister image” to a Facebook Live video broadcast by Diamond Reynolds in July 2016, after her partner Philando Castile was shot by a police officer during a traffic stop in Minnesota. The Facebook video records Castile’s last moments before his death and was viewed millions of times before it was taken down. Autoportrait is a 35mm black and white film portrait of Diamond Reynolds, who stands in intimate distance with the camera, still and quiet (one take is silent, while she sings softly in another). A week before the work debuted at the Chisenhale, the police officer who shot Philando Castile, Jeronimo Yanez, was acquitted of manslaughter.

On that hot August night in New York, Thompson spoke of the feeling of weary inevitability that foreshadows such acquittals – a tragic pattern that includes the acquittal of, or dismissal of charges against, those responsible for the deaths of Tamir Rice, John Crawford, Mike Brown, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Joy Gardner. With smartphones, as well as dash- and body-cams, images of violence against people of colour have become familiar to those of us who can stomach looking. Writer, Tobi Haslett, describes these images in an interview with Thompson: “jerky, blurry footage of Black death—moving images quite literally jolted by crisis. It’s perverse to think of those cell-phone videos of police abuse as comprising a “genre,” but it’s true, they do. Certain formal properties emerge: brevity, pacing, the quality of the image itself. That last is strangely poignant. The pixels have an eloquent ugliness, as technology’s limitations cloud and cut the picture, really forcing us to think of the cheap bits of plastic, metal, and glass that, when bolted and glued together, can capture trauma.”

The notion of inevitability – the inevitability of violence and the non-stop production of this perverse genre – looped in my mind in the days following: a Friday and Saturday. For this Friday and this Saturday produced their own widely distributed images of deadly violence; their own documents of trauma. In Charlottesville, Virginia, white nationalists rallied to protest the removal of a statue of Confederate icon, Robert E. Lee. On the Friday, they marched on the University of Virginia carrying flaming torches and yelling slogans such as “white lives matter” and “blood and soil”. In response, crowds of counter-protesters turned out on the Saturday, and at 1:42pm, a speeding muscle car rammed repeatedly into these anti-racism protestors, killing a 32-year old paralegal named Heather Heyer.

Photography, at times, is the only civic refuge at the disposal of those robbed of citizenship

Living in New York but remaining connected to Aotearoa through the internet, the power of the images being broadcast out of Charlottesville to generate outrage – even far from the site of their violent production – was striking. The events were perceived as unnerving and catastrophic here, of course, but they also fed very real feelings of disquiet in places like Aotearoa too.

The cultural theorist Ariella Azoulay has written extensively about the citizen-making function of photography. She sees photographic images as capable of negotiating relationships between us in spite of where we live or the powers that govern us, conceptualising citizenship as “a framework of partnership and solidarity among those who are governed, a framework that is neither constituted nor circumscribed by the sovereign.”[4] Azoulay’s notion of “deterritorialized citizenship” seems a key consideration in Thompson’s work.[5] It’s in the spirit of solidarity, mediated by images and objects, that Thompson (an artist who whakapapas to Auckland and Fiji) enters into making work that engages Black trauma. It’s this same notion of deterritorialised citizenship that sees Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries being shown in New York City (despite its British subjects) and autoportrait being made for and exhibited in the United Kingdom (despite it’s American subject).[6] Azoulay would argue that photography positions us all as witnesses to trauma.

Photographic witness is fraught with both power and inadequacy. Interviewed about autoportrait for Art in America, Thompson quoted Azoulay: “Photography, at times, is the only civic refuge at the disposal of those robbed of citizenship”. Images such as Diamond Reynolds’s Facebook Live video are desperate documents. They are helpless exertions of the only agency available to their makers in the moment – to record their witness and implore others to believe their victimhood – look I have proof – all their makers can do is hope that they survive alongside the document.

Conditioned by photography’s history, this inadequacy extends into the future – disappointing us when photographic evidence falls short of achieving justice for the victims (Officer Yanez’s acquittal being one example). Of this Thompson has said, “The history of dehumanisation is so long and varied that photographic representation is near irredeemable for people of color.” This history includes not only photography’s role in fixing images of colonised bodies in order to subjugate them via shonky scientific racism, but also the enormous body of images of black and brown faces that has been generated through police mug shots – a form that Thompson traces as an influence on Warhol’s screen tests, while identifying the general absence of people of colour within Warhol’s archive[7] – as well as the calibration of film stock and photographic equipment to white skin tones, which has rendered the Black body in shadow; oftentimes featureless or literally erased. With this history at its back, and the failure of Diamond Reynolds’s image-making to secure justice for Philando Castile in the justice system, autoportrait is poignant as a site where it is possible for Reynolds to exert her own agency.[8]

Aesthetically, tactics of refusal are apparent in Thompson’s film works. At first I wondered whether this was one of the ethical questions his work raises – are we allowed to find it beautiful? Now I’ve come to think that this is fundamental to these works. Vis-à-vis the digitally distributed “jerky, blurry footage of Black death” described by Haslett, Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries and autoportrait are highly produced black and white films. To produce each work, numerous takes were filmed, from which these final ones were selected. Between takes, technical adjustments were made and Thompson and the subjects worked together to refine their performances.

In understanding that Thompson’s subjects are performing, we can recognise the tension between them and the camera – they are attempting to “beat” the camera, in some sense, by withholding a part of themselves from depiction (perhaps the metaphysical escape Thompson struggles to articulate). Thompson himself has highlighted this “underperformance” as a feature of the work, speaking of the considerable energy it takes to repress emotion for the length of the film reel,[9] and of the way the subjects hold the audience at arm’s reach, only occasionally letting us in for a moment of connection.[10]

These works have a restorative intent, allowing their subjects the opportunity to perform the agency and control that was denied to them in moments of trauma. Their silence functions in opposition to the way that victims are asked to re-live their trauma for us in media interviews and on talk shows, and their beauty works against the vast archive of desperate documents that led Thompson to describe photography as “near irredeemable for people of colour.” If photography has come to be one of the strategies through which institutional power is exerted, Thompson and his subjects use all the tactics they can to achieve beauty in spite of the medium.[11]

HEY, YOU THERE!

The philosopher Louis Althusser was interested in how power is exerted both by force and through ideology. He used the idea of interpellation to describe how our identities are constituted through the internalisation of ideology. His classic example is being hailed on the street by a police officer who yells, “Hey, you there!” He argues that in turning around and responding “Who, me?”, you recognise the officer’s request, acknowledging the power of the State upon you – and constructing yourself as a subject of the State.

Since “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” was published in 1970, Althusser’s choice of example has only become more fraught with bitter truth. Here in New York City, the NYPD has come under criticism for their practice of “stop-and-frisk”, which disproportionately sees young African-Americans and Latinxs stopped for questioning, despite no evidence of wrongdoing being found in almost 90% of cases. At his artist talk in New York, Thompson cited the condition of “walking while Black” to articulate the way that people of colour are subject to scrutiny that can lead to their victimization – as in the case of Eric Garner, who was killed by police after they tackled him when they suspected him of selling loose cigarettes.

It’s this condition of “walking while Black” that Thompson traced in Eventually they introduced me to the people I immediately recognized as those who would take me out anyway, the work he made for the New Museum Triennial in 2015. Visitors to the museum met a performer, who briefly acknowledged them, before setting off at a brisk pace around the city, by foot and by subway. The duration of the performance stretched to several hours, depending on the particular journey, and the performer did not interact with their followers again until the end, when they would acknowledge the work had concluded. The performers were all African-American and the journeys traced sites of Black history, both collective and personal. Thompson has described them as sites where subjects’ awareness of their identity was heightened, which is to say the work traced the interpellation of Black subjects in New York City – the way that Black identity is (partially) constituted by the relentless and racialised scrutiny of apparatuses of power.

This work, most of all, manifests the uneasy contradictions of Luke Willis Thompson’s practice. The interpretive information provided to the audience was so light; the authorship so muddled; the work so experiential, that the subjectivity of the work was shattered into an infinite number of fragments.

First of all, what are we to make of the performing that is taking place here? Thompson is particularly fond of Tobi Haslett’s (one of the performers of this work), description of feeling like “both a camera and a dolly” – in that his body was both the subject of the audience’s gaze and framed their view of the surrounding streetscapes. With this in mind, Thompson was also (as he acknowledges in an email exchange with Tavi Nyong’o), asking the performers to “become an image” and occupy a zone in which their individual subjectivity intermingled with generic Black experience. The subjectivity of the artist and performers was also scrambled by the joint authorship of the work. Thompson established parameters for the work, but the performers played a role in determining the journeys that they would perform, based on their own experiences as well as sampling from other narratives of Black history. This sampling and intermingling, and the interchange between the individual and the generic, is the most troubling aspect of the work because it throws up questions about the limits of working with the experiences of others, and the right to draw on (or even, arguably, reperform) their trauma.

This is to say that the work might urge a shared accountability – asking the audience to recognise that they are all complicit in the apparatuses of power that victimise the Black body

One way to interpret this muddled subjectivity is to see it as a challenge. If we accept this interchange between individual and generic Black experience, it’s also possible that a similar exchange occurs among the non-Black audience of this work. This is to say that the work might urge a shared accountability – asking the audience to recognise that they are all complicit in the apparatuses of power that victimise the Black body (where Thompson, who is solely attributed as the artist for this work, sees his own subjectivity falling within this spectrum is another, unanswered question). This interpretation is consistent with the voyeurism that this work asks its audience to perform. Thompson sets up the conditions for the audience to enact relentless scrutiny upon the performers’ bodies. Their gaze is hypervoyeuristic to the point where the work is dependent upon this voyeurism as a hinge for the audience to experience difference, disorientation, and discomfort.

Apparently it was the moments during the work when the performers turned to check if the audience were still following, briefly meeting their gaze, that audience members found particularly disconcerting. These moments, likely not consciously planned by Thompson or the performers, locate their power as moments when the performer gazes back – literally and symbolically. In having their gaze met, the audience was forced to recognise an intersubjectivity that was taking place – in the meeting of gazes, each subject negotiated the constitution of their identity in the eyes of the other.

INDEXES AND EXITS

Luke Willis Thompson’s work constructs avenues for negotiation and refusal, but whether this is a temporary or permanent state of change is up for debate. Thompson has spoken of Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries as a work in which Brandon and Graeme are allowed to exit from the condition of being constituted by trauma or post-trauma. Autoportrait can be seen as doing the same for Diamond Reynolds. Thompson’s prior, non-filmic works, such as Sucu Mate/Born Dead and Untitled could also be described as engaged with this “exiting”.

Sucu Mate/Born Dead is a work that has been shown several times, including at the Asia Pacific Triennial in 2015. It features unmarked gravestones from the Chinese section of a Fijian cemetery, loaned from authorities in Fiji for a period of two years (in exchange for their cleaning and care). The gravestones are those of Chinese labourers from a colonial sugar plantation, who were exploited and abused as a source of cheap labour. The duration of their loan to Thompson and his care for them can be seen as a pause that offers respite from their usual condition – neglected in an area susceptible to flooding at the bottom of the cemetery, located below the sections designated for colonisers and indigenous Fijians.

Untitled, first shown at Te Tuhi in 2012, features three garage doors. In 2008, Auckland teenager Pihema Cameron tagged these doors, leading to his death when the owner of the property followed and stabbed him. The property owner was found not guilty of murder, and was instead convicted of manslaughter, sentenced to serve only four-years and three-months. The doors were bought by Thompson following negotiations with the property owner, and because of his ownership, this work doesn’t just offer pause. Instead the objects are entered into an extended state of elevation. Framed by the gallery space, the roller doors take on a monumental scale, and their showings at the 5th Auckland Triennial and Thompson’s Institute of Modern Art exhibition have made use of their presence to block and control the movement of visitors across the space.

A divisive tension is especially obvious in these works, perhaps because of the indexical nature of the objects and images. Do such works successfully mediate trauma, or do they reproduce trauma for the benefit of the artist and the audience? And in considering our own interpretations of the work, who do we presume the audience to be?

Your own answer to these questions might depend on how successful you think Thompson’s play with the limits of the art institution has been. Thompson operates within the relatively rarefied context of contemporary art. But his practice to date has actively tested the power of the institution to alter the conditions of an object, image, or place.

Works such as Sucu Mate/Born Dead and Untitled bring objects into the gallery, testing whether this shift is capable of intervening in the histories of trauma that the objects are embedded in. An even earlier work, Yaw (2011) saw Thompson borrow a life-sized racist figurine (of a man engaged in blackface minstrelsy) from an Epsom antiques dealer, who had kept it on display for decades and refused to sell it. In writing about this work, Danny Butt cited James Clifford followed by Foucault: “the classification of objects by collectors is doomed to be a temporary exercise, as objects do not remain in the value regimes of either artistic masterpiece or cultural artefact, but shift between them over time and space. For Foucault, the emergence and decline of stable discourses about objects is precisely the source of their aesthetic power: in the modern paradigm the most powerful artistic experience involves something we thought we knew slipping from our grasp, or something felt which is about to become knowable.” It is Thompson’s audacity in attempting these shifts in register with the most difficult of subjects, that is the source of both his work’s effectiveness and its discontent.

Eventually they introduced… and inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam, engage the opposite tactic, though with similar intentions to trigger recognition of these shifts in register, if not the shifts themselves. These works led the audience away from the gallery, treating “real world” environments as a kind of readymade. In doing so they test the power of the institutional shadow that follows them out of the gallery to transform the audience’s perception of (or perhaps even the conditions of, briefly,) the “real world”. Thompson’s recent film works, Autoportrait and Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, explore yet another tactic – doubling down on the division between the gallery space and the outside world, making use of the potentially protective character of the institution. Making the most of the highly controlled conditions of the institution, Thompson sets up an environment for viewing images that is insulated from the free-flowing virality of the internet.

The function of art (and galleries and museums) has always included an element of record-keeping, history-making, and conservation. And in testing the ability of art to mediate trauma, Thompson’s work walks the line between mediation and memorial. In Sucu Mate/Born Dead and Untitled, the function of the gravestones and garage doors as markers is heightened. To me, there’s a visual resonance between these two works that draws out the headstone-like character of the garage doors in their occupation of the white cube. One is acutely aware that their relationship to “real world” trauma is indexical. Even in autoportrait, the life span of an image was a key consideration, with Reynolds urging Thompson to consider the preservation of the film and how the images “might operate, or operate differently, 20 years from now.”

Artists have always played a role in civic society as memorial makers. The Confederate statue that white nationalists protested against removing in Charlottesville is the work of an artist, and respect for its perceived artistic value is one argument that surfaced among those who sought its preservation – including President Trump, who tweeted that such removals were a “loss of beauty”. Althusser considered art and other cultural activities as ideological instruments. This tension only gives Thompson’s desire to facilitate an exit from trauma greater urgency. Public memorials are undoubtedly an ideological apparatus that wield power by signifying what stories matter – and who matters – in society. But recognising art’s complicity in this, Thompson’s work, alongside that of many other artists, is a tactical assertion of art’s ability to also erect signs that point to counter narratives. Instead of answering with “Who, me?”, Thompson’s subjects demand that we call them by their own names.

*

There is perhaps no singular, nor easy, answer to the ethical questions Thompson’s work raises (and they certainly don’t pertain to his work alone). Okwui Enwezor has argued that class struggle is no longer the “organising instrument” of contemporary art – instead contemporary art orients itself around human rights, making ethics the central question it interrogates. This is accompanied by an interest in confronting the conditionality of truth. I am reminded of this when I consider how the intersection of Luke Willis Thompson’s mobility and identity complicate interpretations of his work.

In Aotearoa New Zealand colonisation has shaped our idea of being “other” or being a “person of colour” around our own dominant minorities: Māori, Pasifika, and Asian. In other nations, this terrain of otherness is layered differently. Here in the United States, the ongoing effects of slavery and the nation’s proximity to South America mean that otherness is oriented around Black and Latinx identities to a much greater degree. The question of how “whiteness” is constituted is complicated and fickle. When Kim Kardashian, Armenian by way of her father, recently posed in homage to Jackie O for Interview Magazine’s September issue, the spread was criticised both for seemingly darkening her skin tone to match her daughter (whose father, Kanye West, is Black) and for Kardashian’s daring to emulate a WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) icon.

Making work in Britain about both Black British and African American subjects, Luke Willis Thompson opens himself up to criticism because he is not Black. Moreover, whereas in Aotearoa we might understand Thompson as a person of colour, in the UK and the US he might be read as white (as evidenced by the question of how he reconciles his “white privilege” at the Chisenhale). Being white, or passing as white is accompanied by its own privilege. But there is a question here, which has not yet been hashed out, around whether the difference between “white” and “non-Black” is a distinction worth drawing.

One thinks of the white painter, Dana Schutz, and recent controversy over the inclusion of her painting Open Casket in the Whitney Biennial. Open Casket is a painting of Emmett Till who was kidnapped and killed after he was falsely accused of flirting with a white cashier, and is from a series of paintings Schutz made in response to the killing of Black men in police shootings during the summer of 2016. In an open letter to the Whitney requesting the painting’s removal, the British artist Hannah Black wrote, “those non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights.”

Thompson though, is not ensconsed in a studio in Brooklyn, painting from a photograph he found online. For his recent works he has sought out his subjects, entered into negotiations of both legal and emotional terms, then worked with them to create the work. He is listed as the artist and the subjects are named in accompanying texts. As a curator, I also wonder whether there’s any real ethical distinction between Thompson’s way of working and the dynamic of a white curator showing an artist of colour. Both are seeking to open up spaces for others, and both benefit (non-financially and potentially financially) from doing so.

I do believe that Thompson’s film works offer space for Diamond Reynolds, and Brandon and Graeme, to exert their own agency. I believe in Thompson’s intentions and admire his tactics, while remaining attuned to the discomfort that arises from him instrumentalising others’ trauma in ways that may benefit him as an artist. To my mind, these are not mutually exclusive.

Thompson’s work is rife with these tensions. And in thinking through them, searching for answers, we might negotiate our personal limits – finding the point at which we’re willing to put a stake in the ground, marking our own ethical and moral boundaries. And this, I think, is a worthy function of contemporary art.

It’s easy to feel tested by Luke Willis Thompson’s work, not least because he himself compared it to a Rorschach test. But it is, in a sense, necessary for us to abandon some of our own control, in order to allow Thompson and the subjects of his works to exert their agency. In referencing the Rorschach test, Thompson surfaces the possibility that (viewers and) reviewers of his work necessarily lose some of their self-determination – it’s not that reading inthisholeonthisislandwhereiam as a portrait of gentrification over maternal love is wrong, it’s just that it forces you to recognise that you are a subject too, one constituted by the work – you are being interpellated by the work.

[1] Another example of a tactic is Metiria Turei taking in flatmates to subsidise the cost of her rent (while telling Work and Income that she was living alone with her daughter) in order to obtain welfare support (which is strategically administered by WINZ as an apparatus of the State). Certeau’s classic example is that “the City” is constructed by the strategies of the state and other institutions, which produce instruments such as maps to exert unified control. But on the street, an individual moving through the city might weave, forming tactical paths (like shortcuts) that suit their own agendas, in spite of the institution’s plans.

[2] Luke Willis Thompson, artist talk at the Swiss Institute (New York), 10 August 2017.

[3] Ibid. Thompson was speaking with regard to the historical use of photography as a means of colonial control (imaging the bodies of the colonised). Thompson suggested that he doesn’t quite believe this, suggesting that there might be something metaphysical that escapes being fixed by the coloniser’s apparatus. He noted that this idea is somewhat untested and he struggles to speak to it.

[4] Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008) 23.

[5] Ibid, 25.

[6] This is not to say that there are not still ethical questions that arise from Thompson’s engagement with experiences of violence that are beyond his own cultural experience, as explored at other points in this essay

[7] Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries makes use of the Bolex camera Kodak Tri-X 16mm film setup that Warhol used for his screen tests.

[8] This exertion of agency through image is bittersweet. Autoportrait is, in part, a silent film because anything Reynolds said could have been entered as testimony or counter testimony in the trial of Jeronimo Yanez. For these legal reasons, as well as social ones, Reynolds’s digital life has been shut off. She has been denied an outlet that was a significant part of her life prior to the shooting of Castile. The testimony produced by Reynolds’s bodily performance, fixed on film for Autoportrait, thus becomes a means of expression that eludes the scrutiny of the justice system. But the system’s blindness to testimony not given orally or in text is the same blindness that renders her Facebook live video inadequate in securing justice for Philando Castile. Reynolds was silenced by the legal process, only to be failed by the same legal process.

[9] Alex Quicho, writing about Autoportrait for ArtReview Asia wrote: “Four minutes becomes an eternity under scrutiny. To many of Andy Warhol’s subjects, the Screen Tests (1964–66) were an exercise in self-control. Instructed not to blink into the camera’s flutterless eye, A- and B-list celebrities from Susan Sontag to Edie Sedgwick wrestled with the challenge of appearing themselves. Many crumbled – including the artist Isabelle Collin Dufresne, who, critic Brian Dillon writes, ‘worries that her face simply will not bear such scrutiny, that her image could be quite undone in less than three minutes’.”

[10] Luke Willis Thompson in conversation with Polly Staple, artist talk at the Chisenhale Gallery (London), 24 June 2017.

[11] Thompson has spoken of how he and the crew discussed how to best work against the film itself, in order to successfully image their subjects.