Subduction

A boy jumps from a floating crane and ends up at the bottom of Wellington Harbour.

On a Sunday morning in late March we learned that a body had been pulled from the harbour in our city. The news article said a twenty-year-old man was recovered from the ocean floor. A video showed a red helicopter hovering above the water. Mist curtained the hills behind the modest skyscrapers of downtown. Water and sky were competing shades of grey. The helicopter was unnecessary and obscenely loud in the Sunday calm, even through our laptop’s speakers.

There were pictures showing a gaggle of policemen in their brilliant greenish hi-vis jackets, and the sleek rubber-suited heads of a dive team in the water where the man had died. There was a picture of the dive team helping to lift what looked like a long black bag into an inflatable Zodiac dinghy. Only the straps of the bag were visible. In the final picture, one policeman was almost smiling, turning away from the camera.

The man had jumped from the highest point of a boat, a floating crane. This boat’s engines were steam-powered. It was thought to be the only working crane of its kind left in the world. The man had not meant to die. In fact, it seemed he had died in an attempt to affirm life.

The floating crane’s boom is often clad in scaffolding, blue weatherproof plastic. It seems always under some project of repair. It has been docked in the same berth for a long time, and nearby, an information board shaped like a skinny waist-high lectern says the crane is able to lift one hundred tons and that it was first launched in 1926.

The floating crane is named Hikitia, which is a Māori word that means to lift up or to raise in the arms, and also to carry away.

The police told journalists that the young man who died and his friend climbed the boom of the crane at six in the morning. The crane is forty-five meters from the water at its highest point, about the same height as an eleven-story building.

The twenty-year-olds were friends. They had been drinking, all night perhaps, and when the bars closed they went to a Burger King, dawn not yet breaking.

The harbour is close, in our city, and we are very proud of the long twisty sweep of waterfront, several kilometres in total, with a wide boulevard for joggers and dog-walkers and cyclists. In summer, tiny scarlet blossoms fall from pohutukawa trees and accumulate in drifts and waves on the concrete. There is a calm beach and a marina, breakwaters and restaurants and bars. There is the national museum and, around a headland, a series of tiny rocky bays where penguins and seals can occasionally be seen. The ocean all along this waterfront is clean enough for swimming despite its proximity to the city: the working port itself sits a half-kilometre or more across the bay, container ships and ferry terminals tucked away, at a safe distance.

The floating crane is named Hikitia, which is a Māori word that means to lift up or to raise in the arms, and also to carry away.

But the Hikitia did no real work, and hundreds of people passed it every day. A local fixture, a hulking rusty presence in pleasant contrast to the birdlike yachts in the marina nearby. Much of the downtown waterfront in this city sits on reclaimed land. Some residents are proud of this fact too. See the brass plaques on the sidewalk, in the central business district, only a block from where the twenty-year-old died: Shoreline 1840. Water turned to concrete, in defiance of the earthquakes bubbling up from the faultline that snakes behind the city and continues inland, a faultline built by the endless grind of the Australian and Pacific plates, which meet offshore, very near this city, the southernmost capital city in the world.

There is a diving tower only a stone’s throw from Hikitia, and in summer people leap from the tower into the water. Small crowds often gather to watch the jumpers, who love to spin and flip and send up great plumes of spray, drenching the spectators, many of whom are visiting from faraway countries. The spectators pretend to be irritated, but they often seem glad for the refreshing drops of seawater, and don’t move away.

The man or boy and his friend left Burger King. Did they walk purposefully to the water, or did they wander? They stepped onto the Hikitia and scaled her crane. In this city the southern summer fades quickly, almost a memory by the beginning of March. Dawns come colder and later. Maybe there was a tiny smear of light in the sky above the water. The boy reached the boom’s peak, its rusty pulley and fat steel cables. Did he hesitate? For how long? He jumped.

The police said he hit the water on his back. It’s unclear if this was established through the friend’s statement, or autopsy, or both.

The high-dive world record is fifty-four meters, only nine meters higher than the tip of the crane’s boom. This record has remained unbroken for almost thirty years. The only way to survive a dive from this height is to enter the water feet-first. World-class professional divers attempting to equal or even exceed this record have suffered fractured legs and worse.

A significant amount of scientific research exists regarding high-speed collision with water and its effects on the human body. A dusty schoolbook fact, often-repeated, often-neglected: our bodies are mostly fluid, about sixty-five per cent. It’s easy to forget that the density of the average person is only slightly greater than that of water. Assuming a body weight of seventy kilograms and an unquantifiable drag factor, the boy’s velocity upon impact was roughly twenty-five meters per second, or ninety kilometers per hour. Like being hit by a car.

The boy died in our backyard, or that was how it felt. We’d eaten lunch hundreds of times within sight of Hikitia. Visitors from other cities had remarked on her, photographed the nameplate on her ageing stern. We’d heard the city’s famous southerly winds howl through the rigging of the crane. We’d passed her drunk, distraught, bored, wet, angry, sunburned, euphoric. We grew older, and Hikitia never moved.

A week before the boy died, the same national news conglomerate that broke the story of his death published a brief article concerning the emergence of a semi-viral video originally uploaded a year or two earlier. This video showed a person jumping from the very top of Hikitia’s crane, in broad daylight, a shaky video, a shirtless man silhouetted against flawless summer skies. The man splashed into the water feet-first and surfaced after a moment or two, grinning.

In the news article covering the boy’s death, a brief aside noted that the boom of the Hikitia was at a different position when that video was taken - at an obtuse angle to the boat itself. The tip of the boom was also lower: thirty-six meters. At the time of writing, this video, which was originally posted to Facebook, has received more than eighty thousand views.

*

That afternoon we decided on an aimless Sunday walk, but the tip of the crane on Hikitia drew the eye like the point of a needle. There weren’t many people around. Bad things can happen at the very end of a summer, especially to the young, when months of freedom or calculated risk glide smoothly into the realm of misfortune.

Hikitia’scrane was indeed at a different angle than in the video. It now pointed straight ahead, in line with the bow. The distance from the base of the crane to the edge of the boat itself was significant - seven to eight meters, according to the article we’d read that morning. The jumper had been lucky to clear the rusting steel deck, but it hadn’t saved him.

Weeks earlier, when summer was at its fullest and fattest, we stood in bright sunshine and watched a child, a boy. He was standing at the very top of the dive tower. There was a larger crowd than usual, and the boy was scared, maybe ten years old, staring down the fear, his face oddly still. The crowd’s mood was Saturday-afternoon jovial, and accents from all over the world exhorted the boy to jump. Eventually, the crowd began a countdown. Ten. Nine. Eight. By the count of four there was a strange note of hostility in the crowd’s voice, a mob-style unruliness, palpable desire for action of any kind. The boy jumped on two, arms flailing as he fell. The splash he made seemed very small, and he surfaced, winded but smiling, to applause and cheers not entirely free of irony. Groups of people began to stroll away, chatting, gesturing freely, as if emerging from a movie theatre.

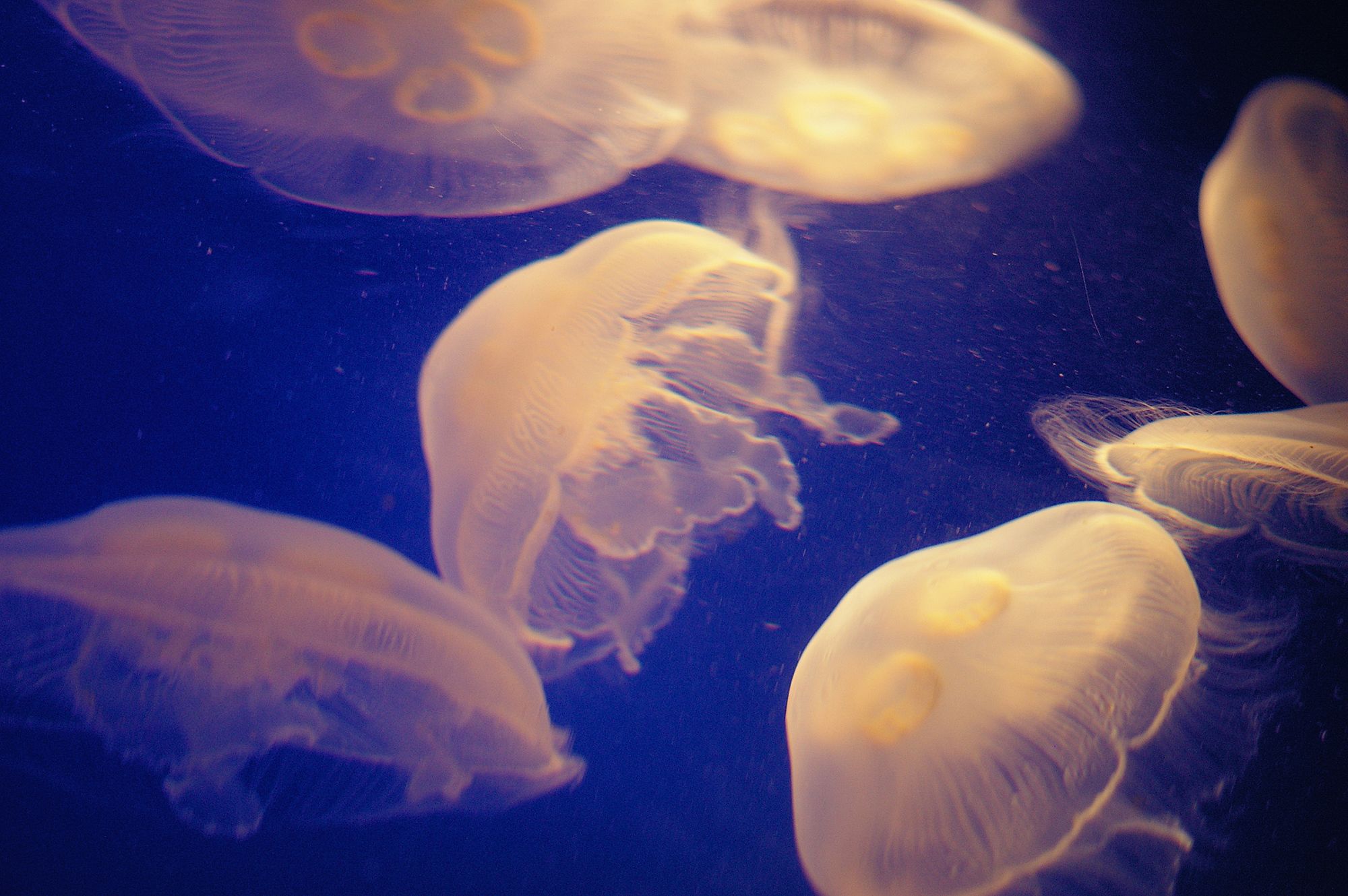

On Sunday afternoon we looked at Hikitia until she began to lose all meaning, one object in a world filled with objects. Near the national museum, a woman tugged at the leash of a small white dog, which sat on the concrete, unmoving, demanding to be carried. Nobody was jumping from the dive tower. Rain had been falling intermittently all day. The air was cool and wet. Autumn was coming down fast, but we were too warm in the jackets we wore. The water was still, and under the reflected clouds on its surface hundreds of harmless jellyfish bobbed and drifted, pale, palm-sized and translucent.

Jellyfish image courtesy Yvonne Chew.