One Foot After Another: A Response to Strands

Kassie Hartendorp takes us on a journey through Strands, an exhibition at The Dowse Art Museum where four Māori artists explore reconnection with their whenua.

Kassie Hartendorp takes us on a journey through Strands, an exhibition at The Dowse Art Museum where four Māori artists explore reconnection with their whenua.

“My friends, do not lose heart. We were made for these times.”

The beginning of 2020 is not a quiet, rolling amble into a new year, but a smoking grenade thrown between the cracks of the Gregorian date mark. In this hemisphere, our holidays are drenched in sun and punctuated by the red of blossoming pōhutukawa. But this year literally looks different as our skies turn yellow and orange from the horrifying bushfires sweeping through the land in Te Whenua Moemoea/Australia. The devastation is too harsh to read about, let alone live through. As political leaders remain silent and ineffective on climate justice, a fog of despair and anxiety settles around our islands. For even if our lands are not physically burning right now, the deities of the volcanoes and earthquakes are lifting their heads, and the rising tides of Tangaroa are greeting our Pacific tuākana in dangerous and unprecedented ways.

It is during this time that I visit the The Dowse Art Museum in Lower Hutt to be present with four Māori artists and their work in Strands, curated by Melanie Oliver. And there is no better time. There is no better time, that is, to be listening to Indigenous people through their art.

STANDING / REACHING

I start with Chevron Hassett’s (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu) photographic series The Children of Māui. The work is anchored by three large photos of his tūrangawaewae: the maunga Hikurangi; the awa of Waiapu; and the great ocean of Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa. Glass beakers, standing on podiums framing the photographs on the wall, hold water from these ancestral sites. In the centre of the room sits a large triangular wooden form called Te Manawa Tapu, which references a poutokomanawa (heart post) from within a whare. Inscribed with a karakia, carved patterns and the photos of the maunga, awa and moana, the pou draws you in as you walk around its white, angular sides.

The work is like a hazy Māori summer daydream. It is an ocean-slick figure fresh out of the waves after a dive, and young boys jumping from a local bridge into cool waters. It is long grass and gumboots and horses without saddles. It is two young women sitting under a tree with their poi by their feet and the urupā just in sight. It is innocent and real: an everyday utopia of rural Māori life beyond the city hustle.

The Children of Māui doesn’t feel like a return, even though it is based on a tūrangawaewae homecoming for Chevron as an adult. It feels like a candid look at the present. It is also a statement outwards: a pepeha proclamation of who Chevron is, and where he comes from. This in itself is a political act in these times.

Would multi-million-dollar-coal-company executives still destroy whenua if that land was known as their great, great grandmother? Would single-use-plastic manufacturers keep choking our planet if they felt the ocean rushing through their veins?

While naming our pepeha is normal in te ao Māori, to align ourselves with the natural world is an anomaly in late-stage capitalism. For many Māori, our ancestral roots have been colonial collateral, and it is not uncommon to walk the world without knowing the shape and feel of our mountains and rivers. By mapping out the physical places that have created him, Chevron has built his own visual tūrangawaewae: a place of heart, solidity and strength.

In the spaces between the photos, I see a grasping and reaching towards something bigger and deeper. The wooden structure symbolises the Polynesian Triangle and our connection to the Pacific. I am heartened by young Māori seeing ourselves as part of the connected ‘sea of islands’ in a political context where governments have gladly divided tangata whenua and tagata o le moana for their own political and economic gain. And yet, the idea of the Polynesian Triangle feels strange and hollow and I am called to follow the challenge of the late Teresia Teaiwa as she often asked – who is this ‘we’ being spoken of?

The Polynesian Triangle is a concept originating from the writing of the French explorer Dumont d'Urville in the 1820s. D’Urville is known for classifying the Pacific Islands into Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia, which are still common terms in use today. But each of these definitions was created by the pen of a European explorer, and bears no relation to the cultures and identities that dwell within Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa. They were strange names, used to draw borders and carve up the Pacific in a way that made sense to the Western world.

As Teresia Teaiwa would also say, however, we learn new knowledge by hooking it onto what we already know – and if the Polynesian Triangle is the hook that reminds us as Māori of our deep ancestral ties to the shores and depths of the Pacific Ocean, then that hook has value. I am hoping the line will lead to richer ways in which we articulate our relationship between the people of the whenua and moana, and Te Manawa Tapu is a grasping, growing expression of this.

UNEARTHING / COMMUNICATING

Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) offers a collection of pieces talking about the learning and retention of Indigenous language. The topic is a relevant one, as language revitalisation work in Aotearoa has resulted in a cultural renaissance in te reo Māori. In the city, free language classes overflow, government organisations clamour to claim their Māori names and the end-of-email ‘ngā mihi’ becomes customary in work exchanges. In many places it has become ‘cool to kōrero’. And thank goddesses. For a language once on the precipice of extinction, a coolness factor is one sign of success.

What we don’t talk about so often is the inequity that exists within learning te reo. By this I mean our city classes are flooded out by well-meaning Pākehā with the time and resources to dedicate to learning te reo, while Māori often find it harder to embark on this same path. Whether it is the ethnic pay gap, or just having more stuff to hold down, Māori can often face unspoken barriers to learning their own language.

The truth is, we are not taking a reo hobby class for fun or interest, we are fulfilling an ancestral obligation in the wake of our culture being systematically destroyed at every level.

Ana’s video work Like everywhere, words come one foot after another speaks into the darkness that relearning an Indigenous language can feel like. The camera is following a torch held by an unseen person who is trekking up a path at night. Surrounded by bush, the trail is often stony and slippery, and the viewer can never see beyond the scope of the torch-light. The destination is unknown and the movements are slow and unsure. Just like my own reo journey, I did not stay around to watch the entire duration of the video. Perhaps it ends on a bright mountain peak as dawn wraps around its ridges. I am not to know, because there is only so much walking through the darkness that someone can endure. What makes that hike easier is the knowledge that you are not alone. And in Ana’s piece, I did not feel alone.

Perhaps the most unspoken feeling is the hurt, or māmae, along the way. The truth is, we are not taking a reo hobby class for fun or interest, we are fulfilling an ancestral obligation in the wake of our culture being systematically destroyed at every level. We call it a ‘journey’ because that is the motherloving truth. It does not begin and end in a workbook, or after a 36-week term. At times it is heavy, terrifying, impossible and deeply, despairingly, sorrowful. You may begin to unearth stories that you have tried to avoid, be forced to face intergenerational trauma, deal with the pain, shame, humiliation, defensiveness and derision of family members. You may have to deal with yourself, in all your own messiness.

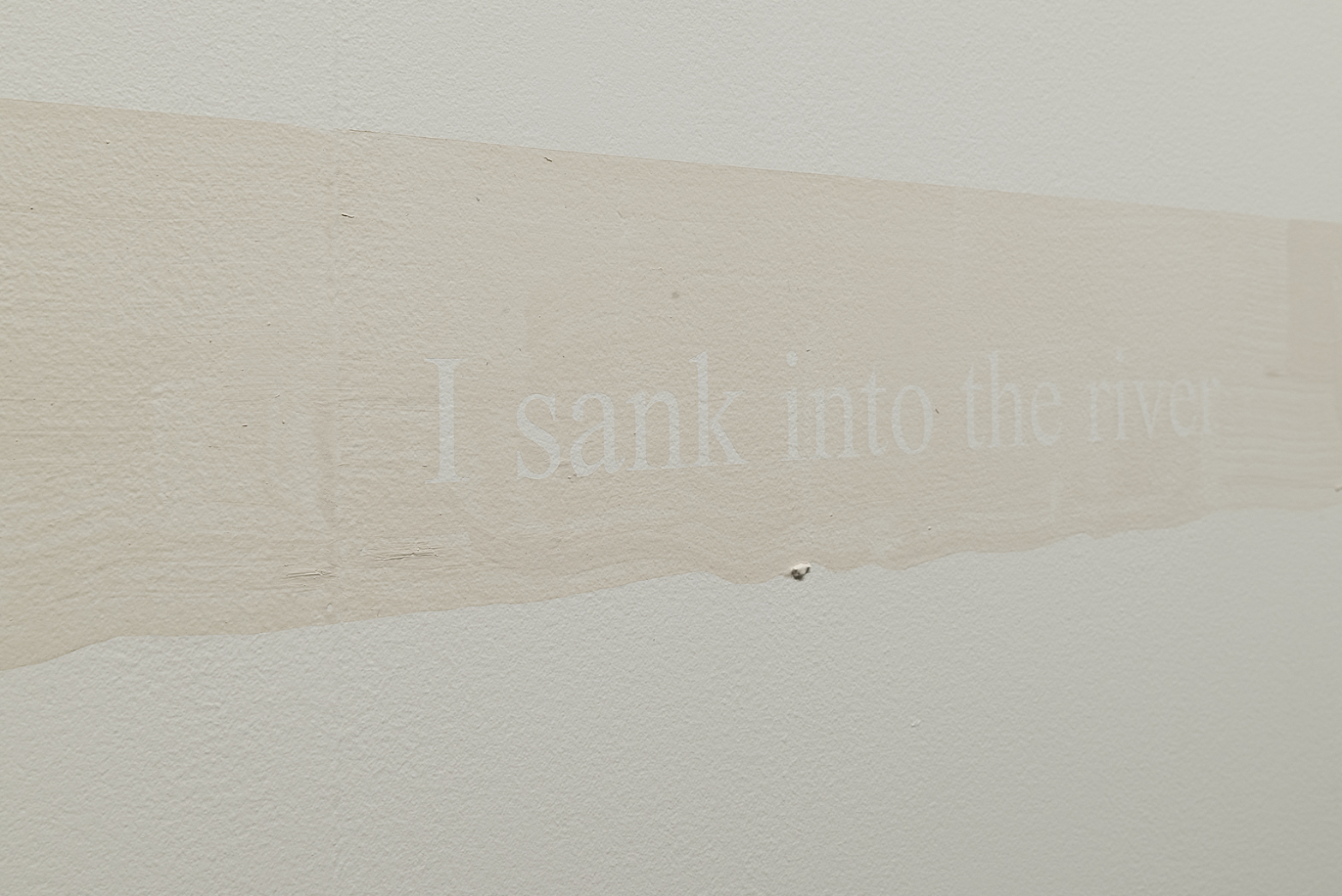

Turning from the video screen, I see what look like huge horizontal brush strokes lining the walls. Each stroke spelling out a poem, Like everywhere, words come one foot after another II is based on the account of a Māori-owned printing press.

In 1859, a group of Māori men, including Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe, travelled to Austria to learn how to use a printing press, and received one as a gift. Back in Aotearoa, Wiremu started up a newspaper in the Waikato, Te Hookioi e Rere Atu Na (The Far-Flying Hookioi of New Zealand). He used the press to disseminate information in support of the Kingitanga and against British settlement, as colonisation intensified. The Waikato War ended the printing enterprise after General Duncan Cameron’s troops brutally attacked Rangiaowhia, which was Wiremu’s home. The press ended up abandoned in the Waikato River, to be re-discovered at a later date.

In Ana’s imagining of this story, the type has been recovered from the awa and speaks back to us in riverbed clays. It is an unearthing of language, a remembering of tools that organised Māori and spoke back to British power before being lost to the currents.

Ana’s works take the narrative further than the printing press could go. She invited Indigenous artists Dean Cross (Worimi, Te Whenua Moemoea) and Anchi Lin (Ciwas, Atayal) to collaborate, and their collective works stretch across time and space. The language in this exhibition asks us to move beyond what is everyday spoken, and think of the depth of Indigenous communication – between cultures and regions, the human and natural world, the living and dead, physical and spiritual, the past, present and future. The possibilities are infinite and already taking place in a million ways right now.

The work is a living, breathing, whispering cross-Indigenous conversation and the result reminds me that our strength lies in the ability to connect with each other as Indigenous communities. Ana’s riverbed poetry asks: “How should we talk to one another? Whistling calls… howling out… at a safe distance… different names.”

I remember an article saying that a shared use of the English language and new information technology has given us, as Indigenous people, the ability to communicate, learn from each other, and support and organise in solidarity across borders. It made me see English in a new light, and gave me hope that even the most violent, globalising histories contain small openings for liberation. After wading through Ana’s riverbed, amid the magpie calls, I feel suddenly and shamefully grateful for the beauty of shared language.

CONNECTING / BREATHING

From one river to another, I move to Arapeta Ashton’s (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Whanaunga, Ngāti Porou, Muriwhenua) work Hā. On a massive screen is a video featuring Arapeta preparing kiekie plants for weaving. Showing a quiet figure working in the shallows of a stream, each frame is a juicy tonic of slow, deliberate preparation. This art form is a sequence of embodied movements – soaking, wringing, wading, tapping, weaving, pulling, tightening. The amount of time and effort that is gifted to this process is awesome in itself. Hovering over the custom-made marae-style viewing seats, the finished kākahu floats above our heads like a golden halo of hand-woven threads.

There is a clear significance in the ‘unbroken knowledge’ of whatu kākahu passed down within Arapeta’s whānau, with each weaver specialising in their own signature work, from tāniko to kahu huruhuru. As takataapui, Arapeta is the first male weaver in five generations. They emphasise the importance of mātauranga Māori in contributing to hapū and iwi. The story told manifests the potential of whakapapa and creativity. The continuing thread of the art practice is just as necessary as the final work itself.

I am drawn in to the process that stretches in multiple dimensions: the kākahu breathing mātauranga Māori into life. The intergenerational flow of knowledge is a rare and precious element in our current world. The richness that we gain from being in ancestral togetherness is powerful. And Arapeta’s work is quietly powerful. In every small action are the many actions of those who came before them. Even their pronouns speak of multitudes.

The fact that Arapeta has learnt this work as takataapui shows how tikanga Māori can expand and embrace; as Moana Jackson has said, “We are all mokopuna.” And of course every mokopuna would have a role and place in the grand, evolving scheme of whakapapa. Hā feels not just like a body of artwork, but a duty, a calling and an act of service back to the wider canon of mātauranga Māori. It is a symbol and a result of the careful weaving of many.

LOOKING / OBSERVING

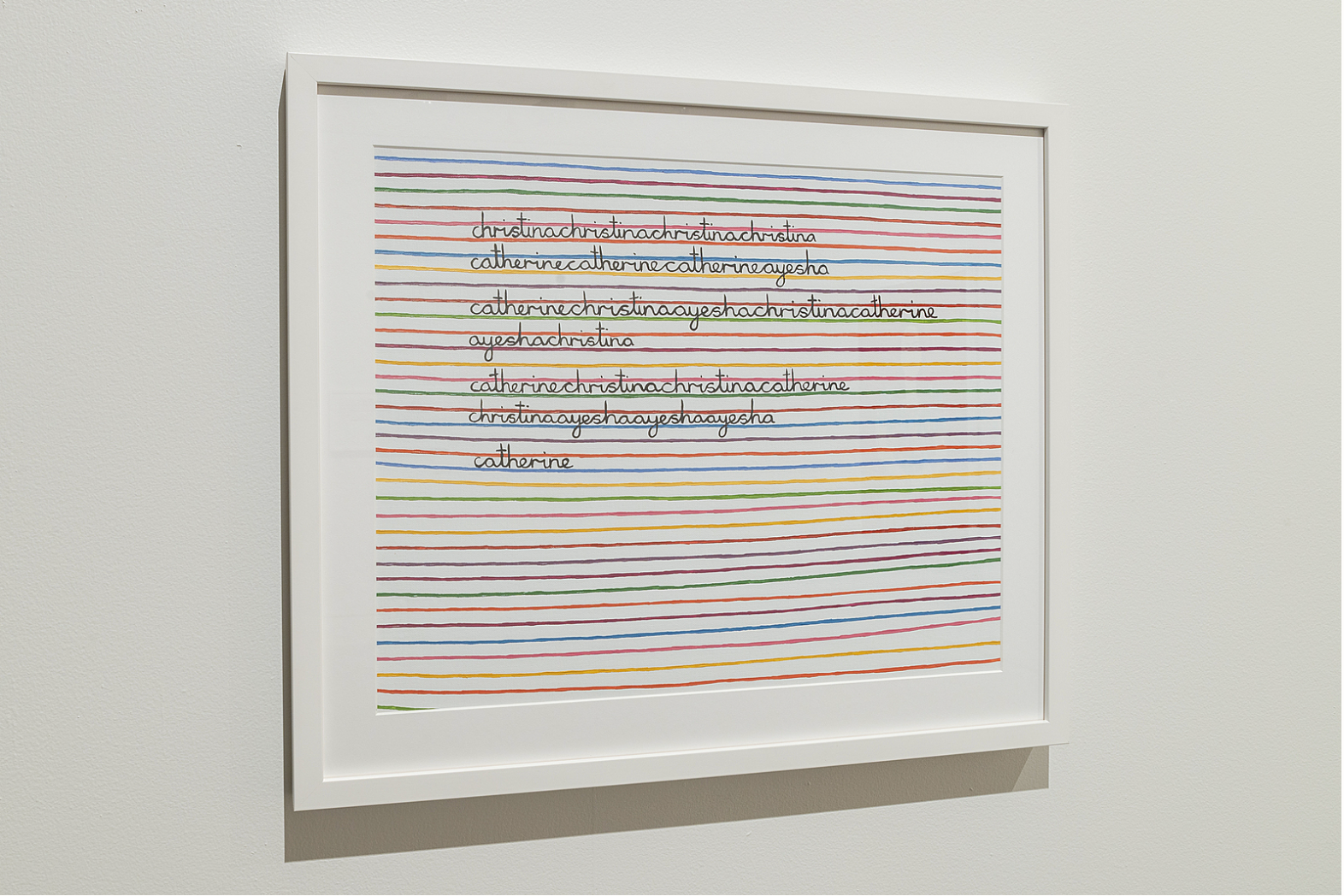

Ayesha Green’s (Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu) work greets me with three large self-portraits, Bedroom, Bathroom and Outside on the back wall, easily catching the eye with their size, colour and simplicity. The paintings show the subject in front of different walls in their old family home. Each piece is a painstaking act of looking, observing and recreating, shown through the clarity of the lines and the detail in the figure’s floral clothing.

There are artworks on either side of the portraits: a series of three handwritten names on perfect straight lines – Ayesha’s, her mother’s and her grandmother’s. Looking like the writing of a young person learning to link their letters, the names run together in different patterns, as if observing and practicing what they all look like next to each other. There is a colourful precision, and it reminds me of being an eight-year-old practicing my signature over and over again, until it merged into my future identity. Seeing the women’s names written together makes me wonder if the three portraits are a merging of whakapapa. Did Ayesha see her mother and grandmother in the curves of her face, or the colour of her eyes? Or did she think more of the way genetics had taken different river routes and braided all three women into very separate people?

The work of reconnecting oneself with whakapapa is, at times, inward and deeply personal. It is being willing to face the ugly parts of family history. I live in a time where the reclamation of whakapapa is a necessary and accepted obligation in the work of re-Indigenisation in Aotearoa.

Yet sometimes we are not prepared for what we may find once we start delving into our collective pasts. In the safe, trusted space of the smoking area down the road from the wānanga, or in a car by the beach, we share our findings in solemn tones. The family secrets that were buried for a reason, the injustices and scandals, and everything in between. This is not the version of the pepeha we give at the mihimihi, or the picture of our ancestors that we portray to the Pākehā world hellbent on racism.

Our whakapapa requires a life-time of observation to make sense of our past and present, and learn whatever lessons we can glean for the future. Everyone I know who has taken this time to look and learn comes out clearer and stronger in the long run. Ayesha’s work makes me think of the courage of looking inward to live outward, and I daydream that she has had whakapapa epiphanies that will serve her for years to come.

“Regarding awakened souls, there have never been more able vessels in the waters than there are right now across the world. And they are fully provisioned and able to signal one another as never before in the history of humankind.”

– Clarissa Pinkola Estes

I leave the exhibition, quietly thanking the artists for their work, and return to my day job as a political community organiser. I am full and determined. As the bushfires continue to rage, local fundraisers pop up on my newsfeed – everyone from punk bands to the drag community are organising events to raise money for those being affected in Te Whenua Moemoea. A young Māori climate activist invites people to join her on the beach for karakia, waiata, banner and art making in response to the fires. Thousands of people are sharing stories and solutions from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities who have been practising cultural burns and climate-honouring ways for tens of thousands of years. I see a press release from a friend who is calling for more Māori to stand against a US/Iran war in the name of peace. I think of all of the lessons that I have learned just from listening to Indigenous artists in my own hometown. To look, to learn, to unearth, to connect, to stand, to reach and to communicate in any shared language we can find. We need all of this to turn the tide on our political path at this time.

Our answers lie in the creative vision of our Indigenous artists; it is not just a luxury but a responsibility to see and hear them if we are to have any hope of protecting our planet and people in the years ahead.

Ngā mihi nui ki a koutou, ko Ayesha, ko Chevron, ko Ana, ko Arapeta mō tā koutou mahi me ō koutou manawa i tēnei wā.

Featuring Arapeta Ashton, Ayesha Green, Chevron Hassett and Ana Iti

Curated by Melanie Oliver

29 Nov 2019 – 22 Mar 2020

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

All images courtesy of the artists and The Dowse Art Museum.