Still an Outsider

Kate Gear on the Chinese poll tax, an oppressive legacy enacted in 1881 to discriminate against Chinese immigrants.

I’m greeted by sizzling woks, aromas, and children and their grandparents conversing in a variety of languages in our local Chinese restaurant. For me, it's not only a time to eat a traditional Chinese meal or to catch up with family and members of the local Chinese community. It's a chance to be in a setting where I am not a minority – where I can be immersed in my culture. A culture that our former policymakers and leaders once tried to eradicate. These restaurants are examples of the places where the Chinese population in Aotearoa have put down their roots. Safe, familiar spaces we can congregate in. But they are also places of unity that allow people of all ethnicities to enter and experience one of my culture's most essential components – food.

I'm half Chinese and half Pākehā. I was born in Aotearoa and am part of the 94th generation of my mother’s family and a third-generation New Zealander. Despite being born here, I've always been categorised as the ‘other’. My tanned skin and dark hair signify that I'm of a minority culture and that people should, therefore, treat me differently. I see this as a continuation of the racism that fuelled and maintained New Zealand’s Chinese poll tax.

The poll tax was enacted under the Chinese Immigrants Act 1881. It meant Chinese immigrants now had to pay a £10 fee to enter New Zealand. There was no entry fee for any other immigrant group. This Act also imposed a tonnage ratio – only one Chinese immigrant could enter New Zealand for every ten tons of the vessel’s tonnage, or cargo capacity. The ship's master had to report to a customs official with the Chinese immigrants' names and ages, and where they had previously lived, on arrival. If they did not comply, they were fined up to £200.

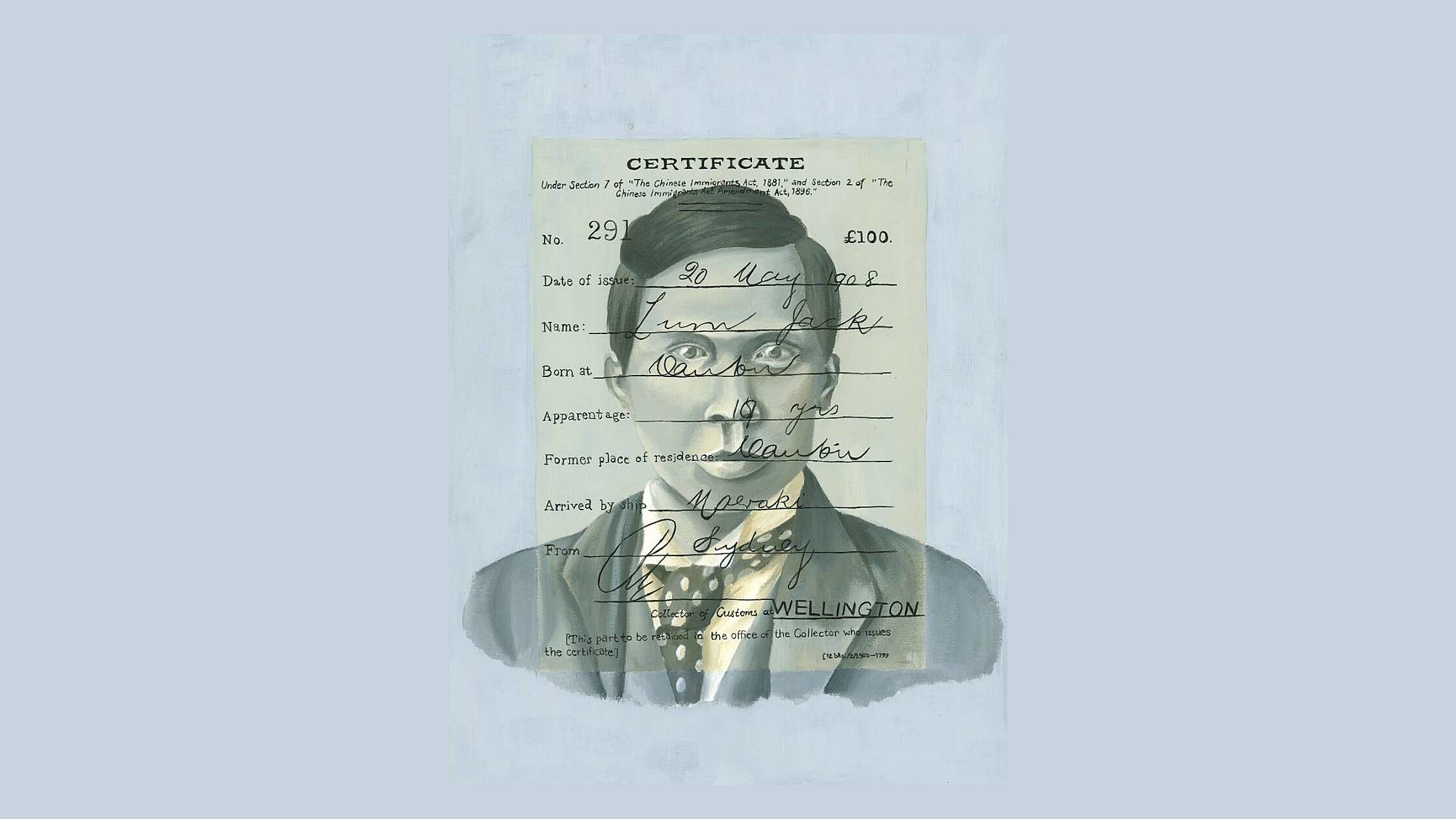

The poll tax was bumped up to £100 in 1896, after Prime Minister Richard Seddon falsely altered census figures to make it look as though there were more Chinese immigrants than there actually were. At the same time, the number of Chinese immigrants allowed to enter New Zealand was reduced. For every 200 tons of their ship’s capacity, only one Chinese immigrant could now enter New Zealand.

Calculated at today’s value, together they paid approximately $39,895 to enter New Zealand

From 1907 onwards, if Chinese immigrants wanted to gain entry into New Zealand, they had to pass an English reading test. Only Chinese immigrants had to pass the test in English; other ethnic groups could be tested in their native language. This demonstrated the importance of English over other languages, such as te reo Māori or Chinese.

During this time, stereotyping was a tool to make local residents in New Zealand fear and vilify Chinese immigrants. Chinese were perceived as diseased, “evil, disgusting, filthy”, as well as “depraved and dangerous”. Those who wanted to keep the Chinese out of New Zealand portrayed all Chinese men as gamblers and opium smokers, who would gather together in their grimy shacks, prey on Pākehā women and coat their vegetables in urine before selling them to Pākehā buyers.

My maternal great-grandfather arrived in New Zealand in 1908, when he was only 19 years old and, on arrival, he paid the £100 poll tax. He had already married my great-grandmother back in China, but it took 12 years for them to save enough money for her to finally join him in 1920. She, too, paid the £100 poll tax. Calculated at today’s value, together my great-grandparents paid approximately $39,895 to enter New Zealand.

Chinese immigrants after 1908 were required to register their thumbprints with customs officials – to ensure another immigrant did not enter under their name. Their right to naturalisation was stripped in 1908, and from 1926 onwards they could not apply for permanent residency. In 1925, to stop the Chinese population from growing, Chinese women were prohibited from coming to New Zealand. Chinese immigrants were aliens.

Poll tax fees stopped in 1934, but the legislation remained until 1944. Its repeal was motivated by World War II, when the Chinese became clear allies in the fight against Japan in the Pacific. Even so, the ban on naturalisation for Chinese immigrants wasn’t lifted until 1951. In 1952, my grandmother was the first Chinese person to be naturalised in Aotearoa.

My great-grandparents were brave to immigrate to New Zealand

My great-grandparents and the rest of the early Chinese community were brave to immigrate to New Zealand. My great-grandfather was sent here by family elders, who hoped he would earn money by working in the goldfields. With little gold left by the time he arrived in Wellington, my great-grandfather settled in the North Island, with my great-grandmother joining him 12 years later. There they opened a market garden and laundry. They always hoped to go back to China but never did.

Whilst it is empowering to know my great-grandparents defied Seddon and his xenophobic ideologies, the legacy of pain persists. Four generations later, I still feel the effects of that legacy of suspicion and mistrust towards Chinese people. If I had immigrated under those same laws, I too would be unwanted here. And although the poll tax and its associated restrictive laws do not exist anymore, this doesn’t mean there are no anti-Chinese, anti-immigrant and pro-Pākehā perspectives in Aotearoa. The poll tax still haunts me. My historical cultural identity as an outsider is maintained through acts of racism ingrained in our society.

Just like my great-grandparents, I experience explicit othering through stereotyping. One of the most blatant forms (especially prominent for me during high school) is name-calling. I was frequently called 'Asian' or 'Kate the Asian'. Sometimes, I was also given racist names such as 'InvAsian', 'Karate Kid' and 'Filthy Foreigner'. It was not uncommon for people to make their eyes into slits, say things in mock-Chinese accents to me, or for people to be surprised when I didn’t do well in maths tests. I am Chinese, therefore I’m supposed to be good at maths. I experience stereotyping as a form of racism all the time.

Today overtly racist and offensive stereotypes have evolved into something more subtle. In 2020, Auckland Grammar School was in the news for a racist skit their prefects performed in front of the school, including a fake awards section where the head boy gave out awards to fake students for being the highest achievers in maths and science. The names of the recipients were "Ching, Chong, Ling", and so on. Christchurch restaurant Bamboozle was criticised in 2018 for their racist menu with dishes like "chirri an garrik prawn dumpring". In an Auckland restaurant, waitstaff referred to a table of diners as 'Asians' on their docket instead of by their table number, not only singling out the table from the rest of the restaurant's patrons but reinforcing the delusion that all people from East Asia look the same.

Being targeted by security staff reinforces my identity as an outsider. Other times, no one will serve me

I, too, experience these types of encounters daily. When entering a store, being targeted by security staff reinforces my identity as an outsider. Other times, no one will serve me. These interactions are so common that I almost don’t notice them. They are racial microaggressions, a type of underhanded comment so subtle that both the person receiving the racism and the perpetrator may not understand what is happening.

I often feel I am untrustworthy. For instance, one time, I was driving along State Highway 1 to Napier with friends. There were barely any cars on the road, and I was driving safely. Still, I was told by others in the vehicle that they weren’t sure if they trusted being driven by an Asian. Similar comments occurred when my family got a dog. I was questioned whether the dog would be safe, because people jokingly believed that my family and I ate dogs and cats. My family has been in Aotearoa for generations, yet there is still a stigma towards us.

During a class at university, we had to share our migration history with a classmate. I was excited to tell my classmate my family's story, and describe the adversities, such as the poll tax, that we have overcome. I was asked where each of my parents was from, and I responded with, "My dad's Pākehā, and my mum’s Chinese, but she was born here." The confusion then started. "Your mum was born in New Zealand?" they asked. I responded with, "Yeah! In Napier." I could see that they were trying to understand how someone Chinese could be born in Aotearoa. They searched for confirmation, asking, "But you said your mum's full Chinese. So, are her parents?" "Of course!" I said, "But her dad was also born in New Zealand." This detail was clearly too confusing. I was asked if my family and I could speak Chinese, or if I'd been to China, to which I responded that now only my grandfather could speak Chinese somewhat fluently and, no, I hadn’t been to China. They gave me a look of unsatisfied resignation and stopped asking questions. Then I was introduced to the class as, “This is Kate, and she’s half Chinese. Well… kind of.”

This is Kate, and she’s half Chinese. Well… kind of

I've had this conversation many times. And every time, I feel drained and diminished. I am amazed that people think that non-European immigrants can't have long histories in Aotearoa. But I also feel like my 'Asian-ness' is being judged – that because I haven't been to China and don't speak Chinese, I'm not really Chinese. My family was required to speak English for the 1907 language test. It is hypocritical for people to perceive me as not Chinese enough because I don’t speak Cantonese. Historic legislation told Chinese immigrants that they had to adhere to Pākehā culture to somewhat belong.

The statue of former Prime Minister Richard Seddon looms tall outside the Beehive. For many Pākehā, his statue is nothing more than a historical artefact of someone who once led settler New Zealand. But as a Chinese New Zealander whose great-grandparents were subjected to the poll tax, his statue represents painful historical trauma. It reminds me that my family elders were unwanted in a country where white privilege was maintained by increasing restrictions on Chinese immigrants. It hurts to know that most people who walk past Seddon's statue will not understand this historical harm.

As someone who has experienced racism, it's hard for me to imagine we will ever be free from it. But despite these negative feelings, I try to remain optimistic. Optimistic that one day I will not feel like an outsider in the country I was born in. That we will become more aware of the poll tax and acknowledge the harm it caused. That we will celebrate and learn about the resilience and inspirational stories of Chinese New Zealanders. Then the poll tax will become a thing of the past, and not something that negatively influences the present.

Feature image: Kate Gear, Great-Grandfather and his Poll Tax Certificate, 2018.

Permission granted by Archives New Zealand to use the following image: ACGV 8836 W1514 L24 2/ L24/16 291 (R23676360), Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, Wellington.