Spinning, Pulling, Stretching with Tempo Dance Festival

Pelenakeke Brown on the urgent and relevant work of three artists in Tempo Dance Festival.

After my kōrero with Cat Ruka, artistic director of Tempo Dance Festival, I had been thinking about decolonising dance and how we can support artists who have not been supported before. I wanted to review three works from the Whatumanawa Season that reflect this expanded understanding of dance and make sense in these critical times. During the early onset of Covid-19, I struggled to think about art and engage with it, especially via technology. I am interested in exploring works and art that feel meaningful in these times, that are thinking about process, decolonisation and accessibility in the digital space. There were many that I engaged with, but these are three that felt especially relevant to explore deeper.

***

BLINDLY FOLLOWING MATISSE: Sarah Houbolt

After watching Blindly Following Matisse I feel like I have woken up from Sarah’s dreams. That I have emerged from the darkness (and playful hues) of Sarah Houbolt’s memories and mind.

The work is performed and audio described by Sarah Houbolt and is captioned and supported by a gentle sound score by H C Cllifford. Hearing Sarah’s voice, reading her words and drifting in and out of her movement for the 16-minute piece feels dreamlike, delightful, and restful.

It begins with a black screen and Sarah uttering words, phrases and descriptions of movement.

Solo dancer

Straight leg

The body sitting enveloped in an atmosphere

Dance, a love of space.

I watch, listen and slowly acquiescence. At first I try to understand the blackness of the screen. If there is something to emerge or view. I imagine what the movement she is saying might look like. But then, I close my eyes and simply listen and notice.

I notice her tone and pace of voice. When she says full extension of the body I pay attention to the emphasis on her words and imagine a little more oomph being added to the movement on the word full.

From the bed dreams are made of.

I think of crip time and how I identify so strongly with this sentiment. That bed is where dreams are made but also where many disabled people (myself included) live and work. Blindly Following Matisse references Matisse, who made his Jazz series from his bed, Sarah celebrates what is found when you really use what you’ve got. This dance film plays with what is possible when you consider the potential of audio description and the visceral elements of dance on film.

Enough of this black screen. Let's begin.

Sarah has agency, in her audio description she directs us, her audience. I have worked with Sarah before around audio description and as she dances I think of her voice saying, “What is the quality of the movement?” The balanced cinematography by Jamie Gray means I often cannot see Sarah's full body or her movement. But it doesn’t matter. Because of her poetic audio description, I can trust the description to know what is occurring but, better yet, receive information around the quality of movement and emotion being relayed to the audience.

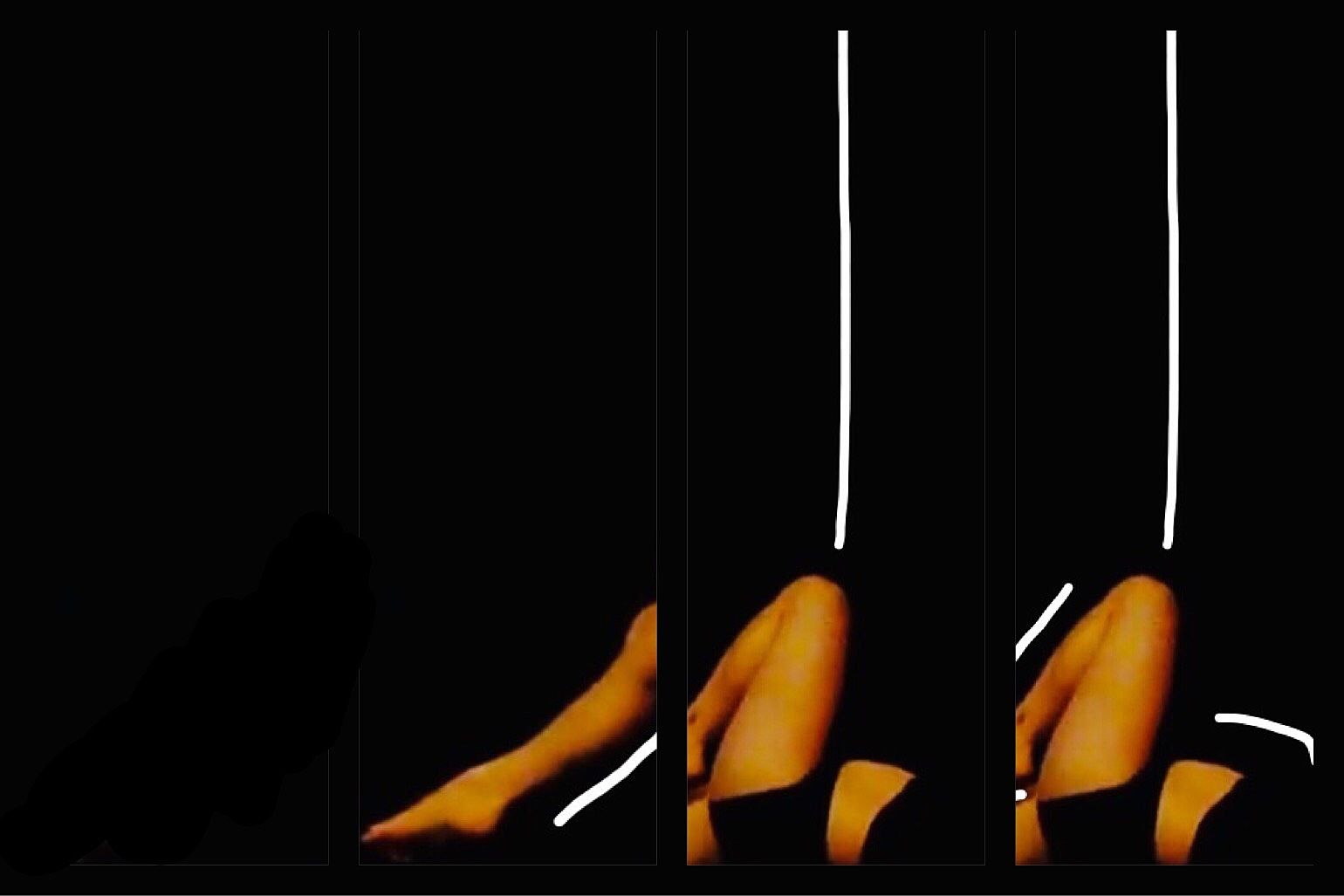

Image description: Sarah is lying on the ground. The knee of her left leg is bent upwards, her right leg seemingly outstretched but cropped out of the photo. Her left foot points to the ground. L-R: Starting midway across the frame her image is repeated three times, pasted on top of each other. White hand-drawn lines frame her body and indicate the leg movement. At the knee, one line travels upwards, trailing off before the edge. The background is black.

I witness and notice Sarah’s agency

We see gentle hues of pink, red and blue. Sometimes Sarah is still and sometimes she is moving. At times there are layers, with two or even three Sarahs moving. It makes me think of vision impairment, blindness and those whose visual impairment includes double vision. Here, it becomes part of the aesthetic. With two or three Sarahs dancing and layered upon each other.

As I witness and notice Sarah’s agency I think back to my experience of disability arts, where there are many works that play with viewing the disabled body and reflecting the non-disabled gaze back at us.

Sparse hair. Distinctive eyes.

When Sarah describes herself the agency in this act goes beyond just looking at the crip body. There’s something more there.

She leaves the space and enters again with a flame. She describes herself conjuring the flame and she traces it along the skin on her arm. As she twirls she describes herself as Icarus falling. I love thinking about Icarus and the sun as divine, feminine, crip beings.

“The revolution will be accessible or it’s no revolution at all.”

Working in the digital sphere as a dance practitioner, I think it can be difficult to translate what is so wonderful about the dance form. I don’t think just dancing in front of a camera is it. As a viewer I want to know why you are moving and how you are expanding what constitutes dance within a world where I am weary of screens. I witness Sarah and her movements that are large and small – that I can and cannot see. Her audio-described short film makes sense in the world that we are living in currently. As disabled activist Mia Mingus says, “The revolution will be accessible or it’s no revolution at all.”

***

WAHAROA: Ella Gilbert

When I think about dance I often think about language. I am a huge fan of dancers who are not trained in dance. I also love grandmothers. And when I viewed many of the Tempo offerings I wanted to engage with works that are using the digital space in really deliberate ways.

Waharoa is a live video-call performance and caught my attention because even with screen fatigue it reminded me why the digital sphere has been so important during lockdown and beyond. “Two relatives, two creatives that share fibre,” Ella Gilbert and Jennifer Shearer, granddaughter and grandmother dance, talk, weave, listen, mirror, remember and cry together.

Image description: A photo of Ella and Jennifer. L-R: Ella is in the midst of a household garden and turned looking towards the viewer, wearing an orange t-shirt and dark-blue shorts with a white line down the edge. Her brown hair is up with a bold fringe; her right hand raised above the waist. Behind, to the side and angled downwards is her left arm. Her knees are bent, and the fingers on her left hand are poised. Positioned closer to the viewer and mirroring Ella's pose is Jennifer, standing on a layer of thick green grass. She is wearing black pants and a dark blue long-sleeved t-shirt dress. A bright sky frames the garden.

I watched from the comfort of my bed and thought of my own grandmother, and of this gift that Ella and Jennifer were sharing with us. The open vulnerability they kept sharing. The willingness to try something new, together. That this was an oral, embodied storytelling in the digital age.

Waharoa – between us – the gate between two people.

It was a mix of the banal – “have you got a tea or a water” – and the awkward stilted moments across the digital space – the ebb and flow of familial connection not often seen on a Zoom call.

For an hour, I watched these artists be tender, honest and awkward. The music by sound designer Grace Bentley acts as little vignettes that break up the time. As a performer I was there for all the tasks, and was fascinated by the way they were interpreted by each. Jen is a potter and she was asked to bring two pieces and then to interpret them. For me the most generative tasks occurred when pottery came into the mix. Instead of giving us a static interpretation Jen inadvertently developed choreographic phrases, which were beautiful.

Using pottery as a framework for many of the tasks was a delightful twist. While Jen sat down and mimed with her hands making teapots and moulding the clay, this was where some magic occurred. Her methodical, thoughtful movements read to me as Jen keeping time, while Ella freestyled on the other screen.

How to be in a relationship with your ancestors

The piece began with questions and ended with questions. These questions reminded me to check in with myself and how important dancing is for all bodies. Many of the questions were ones that I too am grappling with. How to be in a relationship with your ancestors, with yourself in the present and cognisant of the mahi we choose to do that is not just a career choice. Thank you Ella and Jen for spinning, pulling and stretching time, stories and intergenerational movement with us.

***

BEAUTIFUL ANGER: Anu Khapung

Beautiful anger makes me think of the moana.

We, me, are made of water.

With Anu, Sheldon and Celina dancing on the whenua and in their whare they speak of their ancestors, the moana and their relationships. I watch them figuring out relationships across time and space through this collaboration. The superimposing of the moana onto the sky reminds me of the interconnectedness of Indigenous, Māori and Pacific ways of navigating the world.

In the opening image Celina is dancing on the green grass and wearing green. For me, she references the whenua. Anu wears blue in a room with furniture draped in white sheets. I sometimes focus on thinking of them as their own forms of land, lines that could form hills. Sheldon dances in front of a white wall or behind some dead plants. His movements are larger and more embodied.

Image description: A hand-drawn illustration of the three dancers Anu, Sheldon and Celia. The black lines are very fluid. L-R: Anu is standing turned and looking out, wavy hair half up, half down. Sheldon is sitting in the centre, legs crossed, wearing glasses and a bandana. He looks directly at the viewer. Celina stands with one arm on her hip, long hair flowing down. The three figures are drawn with their bodies and lines overlapping. The background is light-green and light-blue with a watercolour effect.

As they move we hear voices speaking thoughts. I don’t know if this text is their own thoughts but it feels like journal entries that they have made.

She thinks broken things are just a sad beauty. And that’s why we keep them shapeless.

We fear an intimate identity.

Anu dancing in a room, her blue ribbon its own movement entity. The shape of Celina’s shirt sleeves billowing in the wind. Sheldon’s shadow behind them adds another layer of movement.

The artists created this work during lockdown and we can feel the intimacy of being alone in large and small spaces. The collages of movement blurring past and present.

This work reminds me of my interview with Cat and the opportunity that Tempo’s digital festival offers movement practitioners in Aotearoa to continue to create work in their homes. A chance to figure out the anteriority of their own body and selves. Here they are shaping mauri and calling to one another, but more importantly, they are calling to themselves.

central

This review is presented in a partnership with Tempo Dance Festival, which covers the cost of paying our writers. We retain all editorial control.