Spec-Fic Month: A Conversation with James McNaughton & Darian Smith

During June 2017, we're celebrating the fantastical, futuristic, and magical with excerpts, interviews, and poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand spec-fic authors. Our first conversation is with James McNaughton and Darian Smith.

During June 2017, we're celebrating the fantastical, futuristic, and magical with interviews, fiction and poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand spec-fic authors. James McNaughton is the author of two spec-fic novels, New Hokkaido and Star Sailors. Darian Smith is the author of five books, most notably the Agents of Kalanon series. Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett geeks out with them about fandom, magic systems, and the genre vs. literature divide.

Sarah Jane Barnett: Tell us about how you started writing and the path that led you to write speculative fiction?

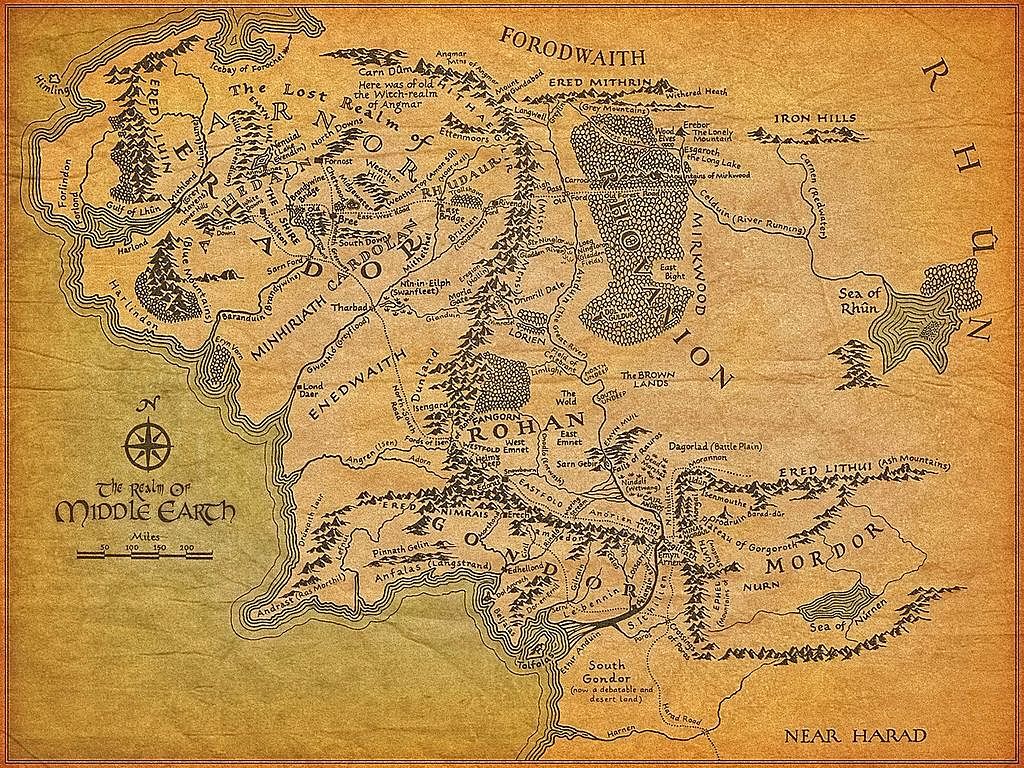

James McNaughton: Pure joy and excitement: I felt that when running home from the mobile library parked at Newlands Mall every month. Seven books was the limit and my bag felt full of magic. I loved CS Lewis, Tolkien, Willard Price and Jack London. (Interestingly, last year an adult called me a bookworm). My bedroom wall featured a much-pored over map of Middle-Earth (which looks deeply familiar, like a face from the past when I see it now).

Writing outside of school began for me with a little magazine I stapled together with my brother, Sam. We used carbon paper and by pushing hard with the pen could manage a print run of three copies (it was important they all be the same). The only story I remember now is one I wrote from our dog’s perspective, with deliberately bad spelling, a kind of ‘day in the life of.’ (Note to younger self: Do not call your puppy White Fang if you live next door to the primary school you attend.) Despite the laughter and mockery that broke out whenever we called her name, I kept reading and writing speculative fiction.

Darian Smith: I was a kid who always loved books. I would get the maximum the library allowed every week and read them all. When it came to writing, I remember at intermediate we were given creative writing assignments. While many kids struggled to hand in a page or two, mine were often around 20 pages and, even back then, were full of magic and adventure.

I always loved speculative fiction growing up – the Narnia books, David Eddings, anything I could get my hands on. I loved the escapism and the ability to comment on our reality in an engaging, interesting way. Plus I loved magic! Who wouldn’t want amazing powers? So at age 16 I started seriously writing my first novel. It was speculative fiction and it was rubbish, of course, but it started me on my journey as a writer. (And no, you may not read that first attempt. Seriously! It was bad!)

Sarah: Your experiences echo mine - as a teenager I loved epic fantasy novels; the magic systems, the flawed yet brave characters. I'd save up my pocket money to buy the next Eddings, and those books still hold a big place in my heart. What do you think is it about speculative fiction that attracts readers, and beyond that, hard-core fandom?

James: Technology isn’t a personal tool anymore but an environment. We’re born into a complex industrial system that demands a regimented and mechanical life. I wonder if dissatisfaction with this comparatively recent development in human history lies at the heart of speculative fiction’s appeal.

A lot of science fiction critiques technology, while fantasy refutes it by going back to simpler times, when personal tools and craftsmanship mattered, and human qualities of skill and courage were decisive in battle. Mystery and magic holds sway in fantasy rather than empirical fact and superior technology, with its fake semblance of magic. I suspect there’s a kind of ancestral memory that can make fantasy feel more real than late-stage industrial capitalism.

Darian: I think there’s something in our psychology that draws us to it. Humans have always told stories of gods and monsters and heroes. Jungian archetypes include the Magician for a reason. We love mythology and magic and having some sort of special relationship with how the world works. The hero’s journey resonates with us on a deep and visceral level – we want to be taken on that journey as well, to feel what it’s like to overcome insurmountable odds and to have the satisfaction, in the end, that things turn out as they should. We see what these flawed characters can do and it inspires us to be (hopefully) better people.

As far as fandom goes, I think heroes inspire loyalty with their willingness to put themselves on the line for others and for a greater purpose. Those are qualities to admire and it makes sense that they would gain a following by doing it. Plus they entertain us and we like that!

As far as fandom goes, heroes inspire loyalty with their willingness to put themselves on the line for others and for a greater purpose.

Sarah: Much has been written about the ‘genre’ versus ‘literature’ divide. One of the issues is the value judgement that comes with it – that ‘literary’ fiction is more worthy than ‘genre’ fiction. In reality, genre writing is a subset of the diverse work that makes up ‘literature,’ but also, labels are useful when discussing different styles of writing.

As an author, there’s sense in simply ignoring the issue and letting readers decide the ‘worth’ of your work, but as some commentators have suggested, New Zealand genre writers receive little public funding. While the distinction between literature/genre seems to be lessening – the Man Booker long listing of Anna Smaill’s The Chimes is a recent example – a 2012 sci-fi issue of the New Yorker was criticised for not including sci-fi by writers from within the genre. How do you feel about the supposed ‘genre’ versus ‘literature’ divide?

James: I think you’re right about the divide lessening (I hope so). On a personal level, both of my speculative fiction novels were published by Victoria University Press and reviewed in mainstream media. May this issue of The Pantograph Punch bring the divide down further! The film and music industry are much more sensible than the book industry about defining what ‘accomplished’ means. Thrillers aren’t judged against the conventions of art house and you don’t have the death metal industry in charge of funding and reviewing dub artists, yet speculative fiction remains condemned for not being literary fiction.

There’s a path available to the young literary writer that doesn’t exist for a speculative fiction writer. New writers must write ‘against’ genre fiction if they hope to do an esteemed writing course, get grants and residencies, reviews in mainstream media and have a ‘literary profile.’ I wonder to what degree that prejudice skews the nation’s fiction output and alienates its readers?

Given that we manage to fund a diverse array of New Zealand music, film and TV, it seems cruel and unusual when it comes to books to leave writers of speculative fiction out in the cold. How about some more support for those learning this craft? I imagine that would result in interesting work and a wider readership for New Zealand fiction.

Shakespeare himself wrote about fairies and a weather controlling sorcerer and nobody ever suggested he wasn’t literary enough to be worthy of Queen Elizabeth’s patronage.

Darian: The divide is definitely a thing. And it’s a pity because there is nothing intrinsically less valuable about genre works. Shakespeare himself wrote about fairies and a weather controlling sorcerer and nobody ever suggested he wasn’t literary enough to be worthy of Queen Elizabeth’s patronage. Literary fiction is, of course, just a genre itself and has its own criteria just like speculative fiction or romance do. I've written literary short fiction myself and enjoyed it, but my first love is fantasy and I struggle when I see that genre deemed somehow less worthy.

I think James is right in pointing out that film and music are good at identifying what makes a piece of work good within the lane that it's in. We haven't been great at doing that within New Zealand literature. Certainly there's a perception that you haven't got a chance at Creative New Zealand funding if you're writing speculative fiction. It's a bit like how rugby is our national sport and the other sports sometimes feel a bit hard done by. Literary has become our national genre but there's as good or better work being done in other genres that it would be great to support!

I think people are starting to push for that to change though. A few years back JAAM did an issue of speculative fiction and I'm very grateful to The Pantograph Punch for shining a spotlight on New Zealand speculative fiction. The NZ Listener had speculative fiction reviews in a recent issue. The conversations are happening and that's a good thing. We can see from the film industry that speculative fiction has a huge audience and it makes sense for New Zealand to show the world what we can do in that arena with books as well as film!

Sarah: VUP has a long history of publishing spec-fic. James, were there other publishers you would have approached? I'm also interested in what you say, Darian, that 'literary has become our national genre.' In your experience, what's the spec-fic scene like in New Zealand, in terms of publishing, collaboration and community? What is your advice for emerging spec-fic writers?

James: Off the top off my head I can’t think of anyone else I could have sent Star Sailors to. VUP are great to work with and I suggest that writers of spec-fic – especially set in a New Zealand context – should consider them as an option. My other piece of advice to spec-fic writers (aside from the usual things that apply to all writers, such as reading, getting feedback, re-writing and learning from failures rather than being defeated) is to join the New Zealand Society of Authors (NZSA). They do a lot of good stuff, but I particularly like their manuscript assessment programme, in which a genre-appropriate reader writes detailed constructive criticism of your work in progress. It's very useful.

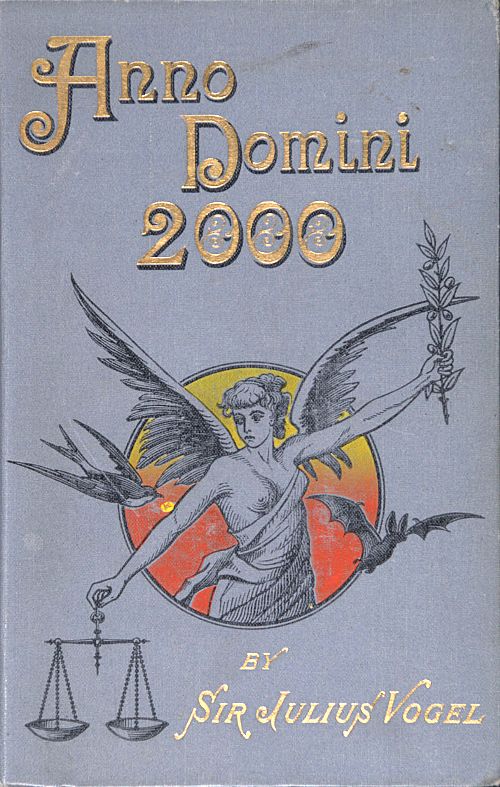

Darian: Spec-fic in New Zealand actually has a long – if somewhat under promoted – history. Sir Julius Vogel, for example, wrote a speculative fiction novel in 1889 and demonstrated even back then that speculative fiction can truly be visionary. His book showed a world with women in power at a time when the Suffrage movement was still a novelty. Today, New Zealand speculative fiction writers have been among the first to embrace new trends in publishing such as indie publishing and ebooks, as well as being incredibly creative with the stories they tell.

In my experience, the spec-fic scene here is incredibly supportive and collaborative. I’ve been lucky to receive help from and have my work acknowledged by other authors. I joined the SpecFicNZ organisation some years ago and through that I was able to meet other writers at various stages of their career; I have combined forces with some of them for opportunities that I couldn’t have taken advantage of on my own.

My advice for emerging writers of any kind is pretty much the same: hone your craft and don’t think you have to go it alone.

There’s a strong sense of community among authors and we like to build each other up and give back to the community at large – you can see this at work in projects like Baby Teeth and The Best of Twisty Christmas Tales, two anthologies that showcase New Zealand authors and donate proceeds to charity. In part, due to New Zealand’s size, the author community and fan community are blended here in a way that is quite remarkable and I think that is one of our strengths.

My advice for emerging writers of any kind is the same: hone your craft and don’t think you have to go it alone. Join organisations like SpecFicNZ and Romance Writers of NZ – even if they aren’t exactly the genre you’re writing – because there is always more to learn and the support you will get from other authors is invaluable.

Sarah: World building is considered the bedrock of good spec-fic and there’s a lot to consider: politics, religion currency, science. Tolkien spent years constructing the Elvish languages, and Patrick Rothfuss created an economy with currency conversion rates. Spec-fic writer Brandon Sanderson has been quoted as saying that it’s the ‘limitations’ placed on a world’s systems that make them interesting. Do you agree? How do you go about building a world that feels real but fantastical?

James: I’m way out of my depth when it comes to the intricacies of systems in epic fantasy. Over to you, Darian.

My speculative worlds are essentially this world, but more so. Star Sailors is set in 2045 because I wanted to explore the consequences of accelerated climate change and social inequality should we continue with business-as-usual. It felt necessary, given the nature of the project, that this future world be plausibly extrapolated from the present, so to make 2045 ‘real’ I studied climate change models and reports and researched the major social unrest that water shortages have already caused in places like Sudan and Syria. Then I talked to experts.

My rule of thumb (outside of ‘essential’ location-setting, whatever that is!) regarding exposition is that something has to matter to a point of view of a character for it to be described. If a thing must be cared about for it to become detailed, the fantasy world becomes an expression of character as well. Stopping the action to explain something makes me feel very uneasy. I prefer to briefly describe and let the reader intuit meaning, or concoct a way of making a detail necessary to the story be important to a character. This minimal approach to detail suits plot-driven stories. Big world immersive spec-fiction, complete with mythology and an alternative thermodynamic system is exactly what a lot of readers of spec-fic want, and while I certainly want to immerse the reader, I’m also wary of slowing down the story with description and back-story. I guess the ‘real, but not quite’ nature of my worlds help in that regard.

My rule of thumb...regarding exposition is that something has to matter to a point of view of a character for it to be described.

Darian: I agree with James in that you don’t want to put too much world building into the book as exposition. There’s a particular balance that needs to be maintained so as to keep the environment of the book interesting but not bog down the story. As a reader, I don’t want to wade through six pages of description about a city and its tax system, for example, but as a writer it may be useful for me to know those details. Tolkien is a great example of an author who created much more of his world than he actually put in the books. (And to be fair, he put quite a lot in the books!)

I’m not nearly as fanatical as Tolkien and certainly don’t have the ability to create entire languages, but I found it useful to spend time thinking about the history, religion, and traditions of the world I’m writing in, and how the individual characters fit within that. I look at real world history, places, and cultures and let those things inspire me. Some of the detail won’t make it into the books but having it in mind helps me write the world more clearly. It also means I have nice little details to include where I can – like the reason Nilarians always wear hats.

For me, the story is about character and action so the world has to support that. Speculative fiction should ideally have an innovative setting but it’s the way in which the characters interact with that world that truly make it interesting. So I do agree with Sanderson’s comment but perhaps with the slight adjustment that it’s how the world’s systems limit the characters that make them interesting. Because it’s how they overcome those limitations that shapes who they are and how they deal with what happens in the story.

Sarah: How important is language in world building – from the names of characters to the vocabulary of a particular society?

Darian: I think language is a big part of world building. I try to give characters from the same country names that feel like they come from the same place or language. Kalan nobles use the province they’re in charge of as a surname, so that provides information as well.

The language of dialogue gives lots of clues about the world and the characters. For example, my characters’ swear words are drawn from their religion so a rougher character might refer to things as 'Hooded' because the Hooded One is the god of death, darkness, animals and scary things in general. If you’re a more genteel character you may use 'Ahpra’s Tears' which references the goddess grieving when the two male gods (her brother and husband) fought each other to the death – which is also the origin story of two major landmarks in Kalanon. So those little hints of language can show something about who the character is and some of the detail of the world.

I also made a conscious choice to be quite modern in the way my characters speak, which some people like and others find odd for a fantasy novel, but I wanted to have a contemporary feel to the book despite it being set in a fantasy world.

I wanted to have a contemporary feel to the book despite it being set in a fantasy world.

Sarah: When creating a speculative world you can remove the sexism, racism, and class issues that appear in our world, or explore the issues in heightened ways. Do you feel an ethical responsibility to do this?

Darian: Yes and no. Sadly, those are issues that are part of a real world and part of human nature so in creating a speculative world, they do need to be considered. That doesn't mean we have to do exactly as the real world does, however. There are definitely opportunities to show the consequences of poor societal choices. I think it comes down to what serves the story. To include a prejudice just for the sake of including the prejudice seems destructive and I would rather normalize a state of non-prejudice where I can. However, a warm fuzzy utopia does make for a dull tale, and there are times when it makes sense for prejudice to have arisen in the world or in the characters themselves. The story is how they deal with it.

There are prejudices that I've made a point of removing in my world. One of my main characters is bisexual, for example, and nobody is bothered by that. Women served as soldiers in the war and have equal rights in this world. However, there is a class system in terms of land owners and non-land owners and spouses don't inherit so power imbalances within relationships do exist. The country is still recovering from an extensive war with a neighbouring nation and so it would be unrealistic to say there is no racism in Kalanon – there is. It's one of the challenges Ylani, as the ambassador of that enemy nation, must face. The relationship between her and Brannon, my main character, is in many ways a metaphor for the process of peace and that, when we get to know people as people, things like racism stop making sense.

Plot can be moral. Speculative fiction taps into the old tradition of story-telling, and I think that archetypal stories... often come with a more clearly announced moral imperative than you generally find in literary fiction.

James: Removing sexism from a world is one way of exploring that issue which realistic fiction can’t. That’s one of the great things about spec-fiction, it allows new and unusual angles on familiar issues and experiences. It feels to me that almost every choice in world creation is politically loaded to some extent, which is exciting, but also exhausting. I agree with Darian that stories have to reflect the real world and its conflicts to a certain degree, or else they’re irrelevant to human experience. In the end, the ethics are explored through the choices the characters make more than the world they inhabit.

Plot can be moral. Speculative fiction taps into the old tradition of story-telling, and I think that archetypal stories, such as the hero’s quest Darian mentioned, often come with a more clearly announced moral imperative than you generally find in literary fiction. I used a marriage plot in Star Sailors, which is comparatively recent compared to ancient plots like the voyage and return. Still, it’s essentially a journey through darkness into light.

Yes, I do feel an ethical responsibility, but it isn’t easy to be ethical in fiction. It’s a very murky business. First and foremost, you can’t be preachy – there has to be a compelling reason for the reader to stay on board. And then there’s the problem of presenting an issue for criticism (Look at this! Can you believe this shit is happening?) and having the reader perceive that behaviour as acceptable. For (a grisly) example, one of the Moors murderers was a devotee of Crime and Punishment. For him, the protagonist was a superman unbound by baseless conventional Christian morality – not a horribly deluded tragic figure. He saw what he believed. I think it illustrates something about the importance of approaching a text in good faith and with an open mind when making meaning.

On a less sinister note, a friend told me the other day that while conservatives and liberals both view themselves as the rebels in Star Wars, conservatives view the Empire as ‘big government,’ whereas liberals see it as a military industrial fascist kind of thing. Star Wars is about more than that, of course, but it’s an interesting example of different values being applied to a text.

Sarah: I suppose that leads me to my next question. Can speculative fiction help us figure out how to live better in the future?

Darian: I think so. Storytelling has always been a part of human tradition and we use stories to help us make sense of the world and to explore new possibilities in a safe way. Reading has been shown to develop empathy and speculative fiction embraces the chance to think outside of the usual restrictions of our individual lives. That’s a powerful combination for enabling positive change.

Books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird helped raise black experience into white consciousness.

James: Yes. Despite the slipperiness of fictional ground as a message-bearer, narrative has undeniable power. Take the civil rights movement, for example. Books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird helped raise black experience into white consciousness. They helped lay the ground for change by humanising the unknown.

The aid and disaster management industry have known for a while about the key role of narrative in raising awareness. It may be idealistic of me, but my hope is that ‘cli-fi’ – climate-fiction – (remade on the screen, ideally, for more reach) can dramatize this complex, urgent and yet still mainly abstract crisis. People need to see a problem before they’ll change course – and that’s not happening. Only when we can clearly visualise the problems coming with climate change will we feel motivated as a society to insist on the big changes required. So yes, I think cli-fi can play a role in raising public consciousness, and that spec-fic in general, by making the abstract more concrete, can help make a better future.

Sarah: To finish, tell us one spec-fic author or book that has recently inspired you? Who should we should track down?

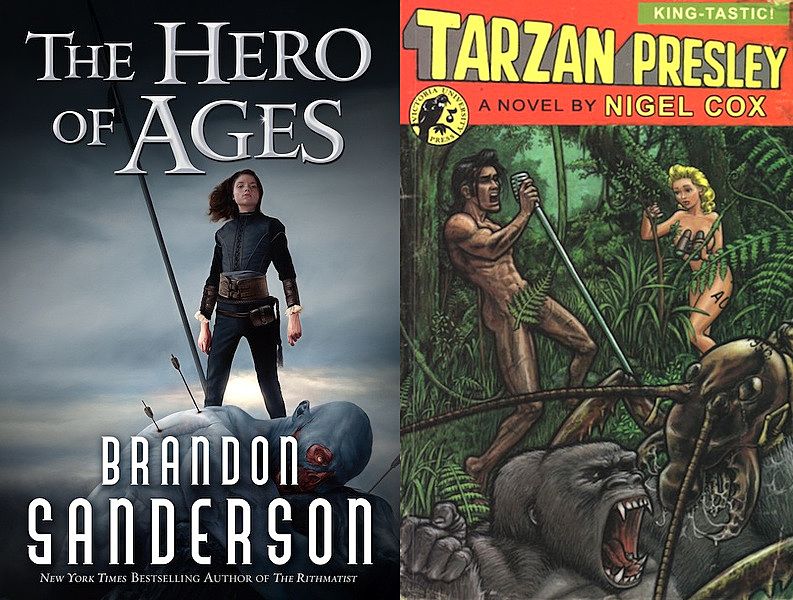

James: There are books I love or am even in awe of that haven’t inspired me to write. It’s a mysterious thing. Nigel Cox’s Tarzan Presley, which imagines that Elvis was raised by gorillas in the Wairarapa, really opened up the possibilities of spec-fic for me. I reckon that Philip K Dick should be tracked down by all those who have not yet.

Darian: I just started reading Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series because I saw a review that compared my work to his and I hadn’t gotten around to reading it yet. I’m really enjoying it, so that’s good! And I recommend just trying New Zealand speculative fiction authors at random. It’s a great way to support the local scene, and often it’s the names that you’ve never heard of that leave you pleasantly surprised.

BUT WAIT... READ THEIR WORK!

A few steps past the gate, the corridor ended with a single locked door. A heavy wheel, like that for steering a ship, was set into the wall and thick chains ran from the barrel behind it and threaded through an aperture in the wall into the room beyond. Magda took hold of the wheel and turned it, winding the chains around the barrel and pulling. A woman’s wild voice screamed behind the door as the chains pulled through...

Read the rest of this excerpt from Starlight's Children by Darian Smith.

The beach was dangerous, excluded from life-insurance policies. The whole coastline was changing and poorly defined, hammered by waves full of hidden debris and prone to unpredictable charges. But there was freedom in this sizzling and thumping no man’s land beyond the seawall...

Read the rest of this excerpt from Star Sailors by James McNaughton.