In the Neighbourhood: Considering 'Space to Dream: Recent Art from South America'

New York-born artist Nelson Cabán reflects on the first comprehensive exhibition of South American art to visit Australasia.

New York-born artist Nelson Cabán reflects on the first comprehensive exhibition of South American art to visit Australasia.

Everyone – almost everyone – agrees. Art-wise, the developing world is having its moment. Not too long ago, knowledge of art from the ‘Global South’ was limited to stalwarts like the cantankerous Mexican couple Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, who remain the Latin American artists de rigeur in the collections of museums and auction houses. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki is determined to help change the paradigm.

Space to Dream: Recent Art from South America is billed as the first exhibition of its kind to come to Australasia, which is surprising given the relative proximity of the two regions. Bringing together a myriad of engaging paintings, sculptures, photographs, installations, textiles, and films from Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay, the exhibition ambitiously spans 60 years of modern and contemporary work, offering a survey of South American visual culture. There’s a lot of work to see; none of it is simple.

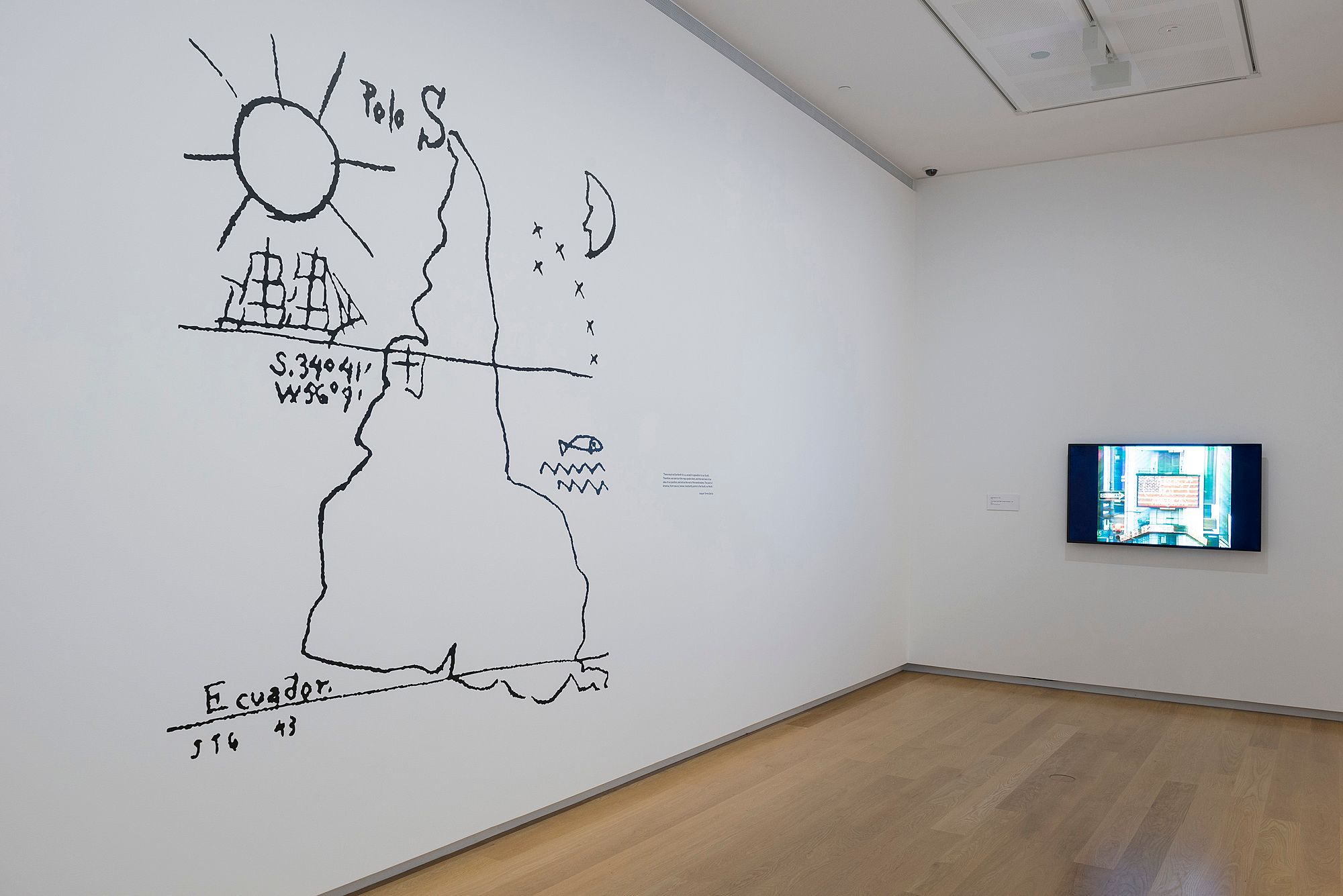

From the outset, the show challenges viewers to discard their preconceived notions (if any) of South America, particularly its position in the world. Immediately, the visitor is confronted with an enlarged version of Joaquín Torres García’s iconic 1943 ink drawing, América Invertida (‘Inverted America’), a proto-conceptual attempt to reverse hierarchies and reposition the South (perceived to be at the edges of the art world) as the North (the established centre of artistic innovation).

Nearby is Alfredo Jaar’s seminal A Logo for America (1987), which calls attention to the exclusionary perception that ‘America’ refers only to the United States and not to the Americas (Las Américas, both North and South), a term originally coined by 16th century cartographer Gerard Mercator for the entire Western Hemisphere. Latin America itself has long been viewed, from the outside, through clichés – a tropical wilderness defined by dictatorships, sugarcane, music, and religion. Language is not passive; it reflects and reinforces dominant narratives that shape geopolitical realities.

Co-curated with prowess by Beatriz Bustos Oyanedel of Chile and Zara Stanhope of New Zealand, Space to Dream itself aims to push beyond the familiar, and that’s what gives it an intriguing conceptual urgency.

Proyecto ADN (‘DNA Project’), a 2012 work by Máximo Corvalán-Pincheira, weaves together personal narrative personal narrative, memory, and tragedy, to speak about the historical and political issues relating to the US-backed dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile and the thousands of desaparecidos (‘disappeared persons’) who were never accounted for after the regime was overthrown. The site-specific installation merges fluorescent tubes, cables, and bone fragments in a distorted helix form, suspended above a shallow pool of water. The work is an unapologetic provocation. All is silent except for the immediacy of the buzzing lights and slowly falling water.

Drawn ever closer, the viewer wonders, “Are those real bones or simply representations?” Whatever the case, the room has been transformed into a sacred space. Recalling the title of the artwork, the broken helix symbolises the incompleteness of tragedy: the unburied corpses, the ‘disappeared’ whose remains were never found. Scientific advances have had a profound effect on processes of closure and reconciliation in nations afflicted by these tragic narratives, but the historical record remains partial, fractured.

These were realities of the mid to late 20th century, not just in Chile, but everywhere on the continent. War was escalating. A military junta controlled Brasil. Paraguay was led by the despotic Alfredo Stroessner, Argentina by the ruthless Jorge Rafael Videla. Racial and class conflicts were intensifying. The state was growing more violent. There were massacres of gold miners in Serra Pelada, Brazil. The ‘Triple A’ death squads terrorised the populations of Chile.

Artists, adaptable to polemic, were tuned into it all, offering disparate and reactionary commentary, often at great personal risk. The late 1960s and 1970s saw a rise in right-wing, neoliberal regimes throughout the continent, which drove many of its most profound artistic talents – Sebastião Salgado, Víctor Jara, and León Ferrari – either underground, overseas, or into the grave.

Paraguayan Joaquín Sánchez’s 2010 video Línea de Agua (‘Water Line’) shows letters carved out of ice by Bolivian migrants in Iquique, Chile, slowly placed upon the country’s coastline and allowed to be carried away by the tide. Initially spelling out No sé nadar (‘I cannot swim’), the waves unhurriedly change the words to No sé nada (‘I do not know anything’). This work explores the historic conflict between Bolivia and Chile during the Pacific War, the War of the Triple Alliance, and the Chaco War, which cut off Bolivian access to the Pacific Ocean in the early 20th century.

Venturing further north, above the equatorial line, we encounter works by the Colombian artist Juan Fernando Herrán. As it happens, Colombia is only country represented in the exhibition from Gran Colombia, the utopian republic founded by the great liberator Simón Bolívar, and the first decolonised territory on the continent. The absence of works from the other countries that formed part of Gran Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, is regrettable.

It would have been beneficial, for instance, to include paintings by Oswaldo Guayasamín, South America’s most notable cubist and a pioneer of indigenous representation within art world networks, both domestic and international. His collaborations with other artists, like the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda and the Argentinean musician Mercedes Sosa, are indicative of a Pan-Andean flow of creative information that one might not expect over such foreboding terrain.

In any case, Herrán’s photographs bring the viewer into the Upper Andes, with its large cities set deep inside mountainous valleys. The hustle and bustle of the central districts extends onto the slopes, where the majority of the population lives, adding a hodgepodge of self-constructed housing, electrical wiring, and water pipes to the foreboding terrain.

The works are based on Herrán’s experience of walking through the hillside slums of Medellín, Colombia, a city made famous – or rather infamous – by the exploits of its native son, the drug kingpin Pablo Escobar. Stairs and walkways are carved into and dug out of the mountainsides, allowing individuals access to the city below and to one another. These geographical adaptations and spontaneous systems of co-dependence are sociological marvels, representing a communitas of economic condition, existing on the margins of society.

Contrasted to the large, rectangular Spanish plazas in the main city, the hills are speckled by spontaneous dots of light, like constellations of fireflies floating in the night sky. In the valley below, the rich eat, eat to excess, watched by a thousand hungry eyes.

Politic realities are inseparable from art, which is often a forceful, direct response to them. With all this tumultuous history serving as a backdrop, a history of intercontinental wars, coups d’état, and state oppression, it would be easy to view South America through these well-worn tropes. But the continent is also home to the melodic sounds of tango, samba, bossa nova, salsa, and cumbia, and of course carnival (carnaval), that celebration of parade floats, glitter, sequins, and firewater, that precedes the Roman Catholic festival of Lent annually.

The Latin passion for life punctuates the social landscape. Children play football on the shores of city beaches and in mountain villages. Men serenade women in public squares amidst army tanks and police barricades. In South America, the body is a fiesta. Cultural tides move in many directions and reality does not necessarily become destiny.

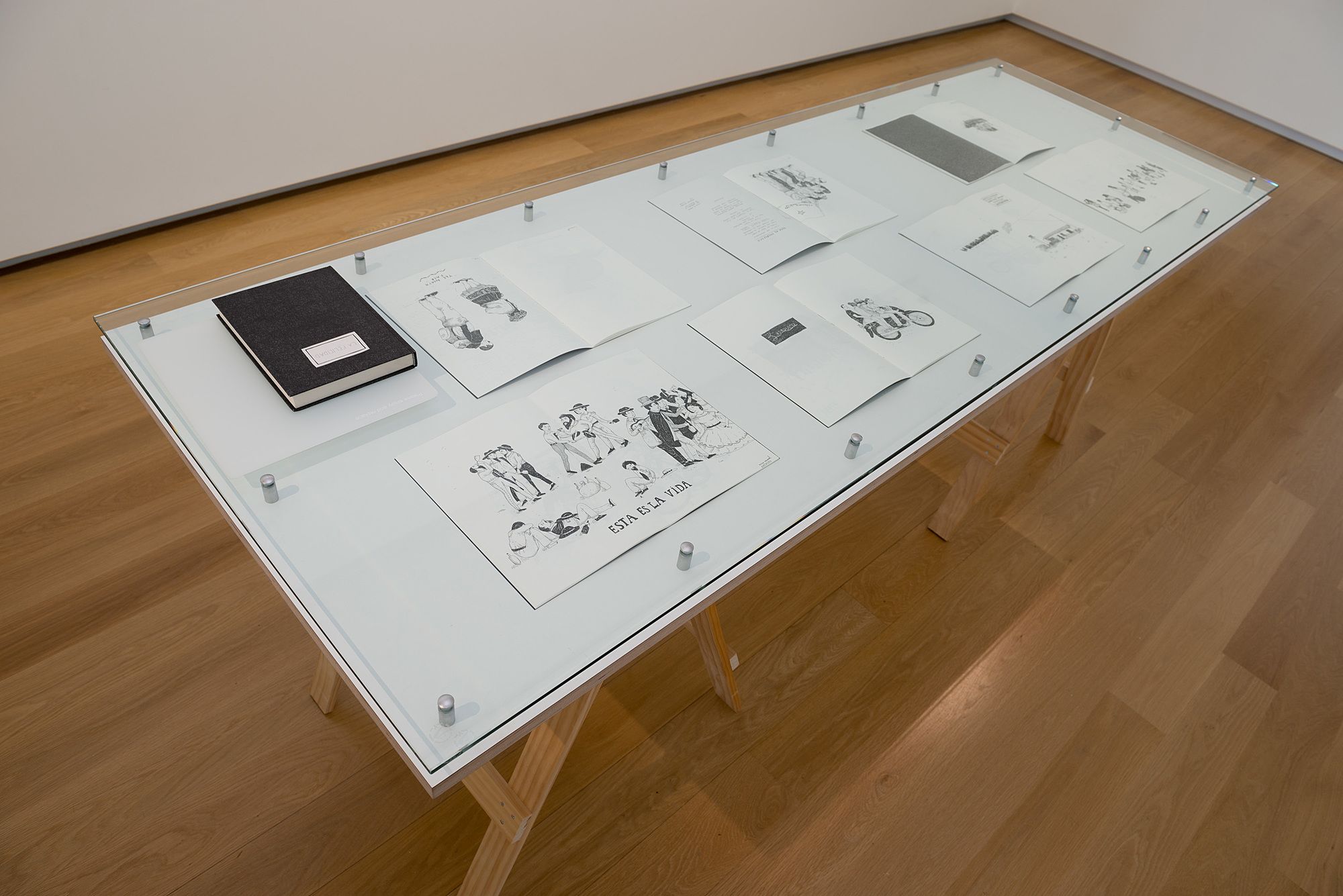

As it turns out, happiness is also a destination in South America. In 2012, Bogota-based, Colombian illustrator Kevin Mancera embarked on a 12-month journey around greater Latin America, venturing to 15 cities named La Felicidad (‘Happiness’) in seven countries. Five were in South America: Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. In some instances, rather ironically, the name of the town had been changed. Some were difficult to reach. Others were completely inaccessible because entry was prohibited. Perhaps La Felicidad eluded Mancera the same way the mythical city of El Dorado evaded the Spanish conquistadors centuries beforehand.

His beautiful ink drawings include images of migration (people with rolling suitcases, public buses with destinations scrawled upon them) and of individuals and places he encountered along the way (food vendors, rugged landscapes, walls plastered with employment notices). What unfolds across the twenty-plus illustrations on display is not only a poetic adventure through South America, but also a whimsical pilgrimage in search of happiness – a journey as universal as any other.

The poignant black and white photographs of Chilean Lotty Rosenfeld belie the serious subject matter that they depict. Her 1987 work, Registro de Cruces (‘Register of Crosses’), deals with intersectionality and the use of public space for political protest.

Normally, street pavements, with their white lane markings, indicate to vehicles and pedestrians alike the appropriate way to traverse the urban landscape. By adding perpendicular lines, Rosenfeld turned the markings into Catholic crosses, causing urban roads and rural highways to take on a sociopolitical dimension. Using these plus signs, she transformed long stretches of road, creating morbid versions of Peru’s famed Nazca lines that recall funeral processions and hint at the brutal acts of the Chilean state under Pinochet.

As a member of CADA, the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (‘Art Actions Collective’), which is also included in the exhibition, Rosenfeld and her compatriots were active during the 1980s, marking the public landscape of the Chilean capital, Santiago, with anonymous messages of political resistance, always at great risk.

The plus symbol evolved into several phrases beginning with ‘no +’, meaning no mas (‘no more’). Coupled with mimetic participation by the Santiago citizenry, messages such as no + violencia (‘no more violence’), no + tortura (‘no more torture’), and no + desaparecidos (‘no more missing persons’) began to appear on the municipal landscape in puissant defiance of the regime’s brutal censorship. Lacking sociopolitical power, the walls and the streets became the publishers of the poor.

This, in a roundabout way, brings me to my main problem with the show: it doesn’t include enough new history. Though broadly celebratory in spirit, Space to Dream relies heavily upon the tropes of poverty, upheaval, and political conflict. This is not entirely without reason. After all, Brazil’s first female president was recently impeached on corruption charges, adding a new narrative to the ongoing, tumultuous political narrative of South America. But in a continent of more than 380 million people, there are certainly many untold and more encouraging stories to be unearthed.

The exhibition also tends to feel ‘exotic’ without being overly informative. It could have done more to bridge the cultural, political, and linguistic divide between New Zealand and its neighbors on the other side of the Pacific.

Ultimately, however, it’s a good start, and Auckland Art Gallery must be commended for attempting to delve into the rich visual tapestry of the too-often-forgotten America. Given the time it has taken to bring the first major survey of art from South America to Australasia, it may be a while before New Zealand plays host to an encore performance. For this reason, this show is important. At this time. In this place. For many, Space to Dream will be a discovery – and isn’t discovery what exhibitions should be for?

Note: This essay was originally written for a competition run by the University of Auckland. It was chosen as the winner by curator Zara Stanhope, co-curator of Space to Dream.