Soothing Words and Bloody Deeds: On Animals and the Law

Eloise Callister-Baker goes to a conference that challenges her diet, and the country's more generally.

Eloise Callister-Baker attends the only dedicated conference for animal law in Aotearoa New Zealand, and comes up against some questions about our national identity.

We call ourselves Kiwis. From the demonym down, our native species are fundamental to how we define ourselves. We come second in the world (only behind the US) for the number of companion animals per household. And of course, the animals we raise, breed, shear, milk and kill for agriculture are central to our economy.

In 1999, our parliament enacted a sophisticated and comprehensive piece of legislation, the Animal Welfare Act. It recognised the five freedoms of animals – the right to proper and sufficient food and water, to adequate shelter, to display normal patterns of behaviour, to appropriate physical handling, and protection from and rapid diagnosis of injury and disease. In 2015, the Act was amended, and one of the most significant changes to the legislation was its recognition that animals are sentient – that they can feel things, remember events, and evaluate risk. In word if not deed, we seem to be ahead of the curve. So why then, has it taken until 2017 for New Zealand to take animal law seriously enough to dedicate a conference to it?

On 1 Jul, I make my way into a lecture theatre in the Sir Paul Reeves Building, at Auckland University of Technology’s business school, for the New Zealand Animal Law Association’s inaugural conference. Unprecedented interest has required the organisers to move it to this larger venue only weeks before the conference date, and 238 people turn up on the day - mostly students and young professionals, fairly evenly divided between law, science, veterinary and other disciplines. Women dominate the attendees list; only 51 men attend the day’s six presentations, and its two panel discussions.

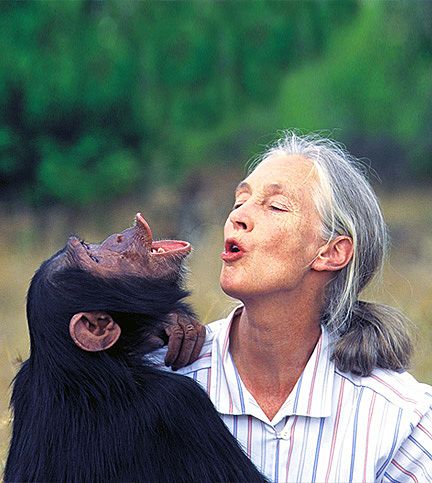

The world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees, Dr Dame Jane Goodall, now in her 80s, opens the conference with a talk on hope in action. She describes her job as “changing attitudes”, and goes on to say said she has never given a talk like this, especially in the context of an animal law conference. Setting the tone, she warns us in her soft, English accent that “the most intellectual animal to ever walk the Earth is destroying its only home.” She urges action, thoughtfulness and, most importantly, compassion. “You need to have the heart involved as well as the mind.”

As for me – I’m attending the conference because I am a lawyer. Though I studied at the University of Otago, the only university in New Zealand to offer a permanent animal law paper, I had never properly considered animal law, and wanted to understand its application and context. But it’s more than that too – I wanted to get my thoughts straight about my relationship with animals.

I’ve never done much for them. I occasionally eat meat (although not since 1 July). I go fishing a few times a year. Unless it’s glaringly obvious, I am not usually aware of how or what animals are used in the food, medical, cosmetic, or clothing products I consume. My family have welcomed goldfish (their names long forgotten), mice (Snippy and Bingo) a rat (Red Rifle), a neighbour’s cat looking for an extra meal (temporarily nicknamed Tiger) and a dog (Cyrus) into our homes. But meat, mostly fish, has always been a part of our family’s diet – although my mother was a vegetarian for over twenty years.

One graduate, soon to be admitted, suggests that killing these so-called ‘predators’ (possums, rats and stoats) cannot be ethically justified and that nature should instead be allowed to run its course, even if this leads to the extinction of some native bird species. Others around him are more dubious.

An hour or so before the conference begins I meet with Marcelo Rodriguez Ferrere, a senior lecturer at the University of Otago and the co-ordinator of the aforementioned animal law paper in a cafe near the AUT campus. Rodriguez Ferrere has spent the morning reading science papers on animal cognition behaviour. Young and enthusiastic, he talks with a passionate and articulate manner at a a volume slightly louder than typical, as if he’s still talking to an audience from the front of a lecture theatre.

Rodriguez Ferrere became interested in animal law while studying for his Master of Laws at the University of Toronto. He had already been thinking about veganism from an environmental perspective, but after moving into a vegan commune, talking with others who lived in the commune and reading the literature they provided him, he became committed to the subject. He read Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, which was first published in 1975. Rodriguez Ferrere describes Animal Liberation as the book that gave “birth of the entire animal rights movement”. Amongst the numerous ideas the book popularised lies the idea that our notions of animal welfare are founded on glaring double standards: we discriminate against different species based on whether we use them, like them or eat them.

The week before the conference, Rodriguez Ferrere was interviewed on Kim Hill’s Radio New Zealand Saturday morning show. During the interview, Hill segwayed from a discussion on animal sentience and the Animal Welfare Act to one about personal lifestyle choices and relationships to animals. Hill acknowledged guilt about her passion for horse riding. Adamant she could never give up honey, she commented that being vegan is perhaps going too far (although later she seemed to become aware of the inconsistency in her comments, the distinction between one form of exploitation and another). Hill’s plight will be familiar to many of us - she feels guilty about her interactions with and consumption of non-human animals, but lacks the ambition to change them.

When it comes to non-human animals, most of us get muddled – the topic often leads to confessions and complicated and inconsistent justifications for our choices. I ask Rodriguez Ferrere about his interview with Hill and talking to people outside of the animal law realm about the subject. “It is for whatever reasons an area of the law that conjures up a whole lot of ideas and views and prejudices, but also at the same time strongly held positions that have little to do with the legal regulation of the area of law and everything to do with people’s lifestyles and moral choices.”

Even in his profession, it’s a narrow area to go looking for understanding. When he explains his concern about the under-importance and inconsistencies in the Animal Welfare Act to other lawyers and academics, he gets the same reaction as he did with Hill. “There’s a lot of sympathy, because they can see the problems with that in the abstract, but of course, the minute I start pushing back too hard it instantly is a reflection on their life choices – what they eat, how they interact with animals. If they go horseriding, if they go duck shooting then my views on the legislation and how it’s important have a direct impact upon their lifestyle and their life choices.” Rodriguez Ferrere has learned to pull back or re-route the conversation. “I’ve always found that putting people on the defensive usually entrenches the views that they already hold, rather than change them.”

In 1977, the first animal law course in the United States was taught in Seton Hall Law School in New Jersey. Following this, only a dozen or so animal law courses were offered in United States’ universities, until Harvard Law School established its first animal law course in 2000. Now, over a hundred law schools in the U.S. offer such courses. The demand for these courses, time and time again, has been driven almost entirely by students. Given the conflicting attitudes towards animals we have in New Zealand, it took a while for the first permanent animal law paper to be established here (any animal law papers that existed before in universities here were only temporary). One of the conference’s other major speakers, retired Australian High Court Justice the Hon Michael Kirby, was an unexpected driving force.

Rodriguez Ferrere joined the University of Otago law faculty in 2012. Partway through his first year of teaching, Kirby gave a guest lecture at the University on what animal law is and why everyone should care. Rodriguez Ferrere says Kirby “laid down the gauntlet” to the dean of the law faculty, Professor Mark Henaghan, by challenging him to introduce an animal law course. Professor Henaghan immediately said he would, and Rodriguez Ferrere was pulled in to take the paper.

“The minute I started doing a bit of digging, more than anything else that struck me was that we have a very sophisticated, progressive and complex law [the Animal Welfare Act 1999] on the books, which has not been enforced or been taken seriously in any way, shape or form.” Kirby saw this too. Rodriguez Ferrere says the new paper was met by scepticism by some staff at the University, but – as has been the case time and time again for similar courses overseas – it was and is widely popular with students.

Just before midday, I slip out of the lecture theatre to have a conversation with Kirby in an empty lecture theatre nearby. Kirby is in his late 70s. He is pesticatarian, openly gay and remains Australia’s longest serving High Court Judge. In 2013, he was appointed Chair of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights Violations in North Korea. Along with Goodall and others, he’s also a patron for Voiceless, a New South Wales-based animal protection institute that works to improve the legal protection of factory-farmed animals and kangaroos in Australia.

"Many people launch books and never actually read the books," Kirby says. "Most people come along and talk about themselves. But in my case I actually read the book and I learned what is involved in the process of raising, transporting, housing and containing, controlling and then slaughtering animals.”

Laying his eyes on a point on the desk in front of him, Kirby rarely looks up during our conversation, delivering clear and comprehensive monologues in response to my few questions. In the 1970s, he was the founding Chairman of the Australian Law Reform Commission. This role at the new independent statutory body took him into re-examining areas of Australian law that needed attention in the face of community concern or technological and scientific change. Around this time, he met Christine Townend, a young novelist and artist who was beginning to dedicate her life to animal welfare (Townend is now one of Australia’s best-known animal rights activists). “She became quite a noisy advocate for animal welfare, trying to get people to realise that just as their dogs and cats were living creatures with sentience and consciousness, so were animals in farms and animals being raised for slaughter or mass farming.”

Kirby began attending Townend’s functions and speaking for her causes. They were attacked for their views, especially by the Australian Cattlemen’s Association (Kirby notes that it is interesting they were the cattlemen, not the cattlewomen – this connection between gender and animal treatment comes up numerous times while we talk). Despite the attacks, Townend began to receive increasing support from politicians who were reacting to their electorates’ growing anxieties about factory farming.

Like the academics and lawyers who Rodriguez Ferrere describes as only sympathising with animal law at a theoretical level, Kirby also distanced himself from practical application of this theorising. “I was still a carnivore, I still tucked into my piece of steak and I didn’t really change that until soon after I left the judicial office.”

After he left in 2009, Kirby was asked to launch a book called Animal Law in Australasia, edited by Peter Sankoff and Steven White, which featured text by experts from Australasia examining the legal relationship between humans and animals. It had a profound impact on him. “It gives you more information than you necessarily want to know about the circumstances in which animals are slaughtered. Many people launch books and never actually read the books. Most people come along and talk about themselves. But in my case I actually read the book and I learned what is involved in the process of raising, transporting, housing and containing, controlling and then slaughtering animals.”

Just as he turned 70, and well past the ordinary retirement age, Kirby’s relationship with animal law was shaken from the theoretical realm to the realm of the everyday. He simply had to change the choices he made. “That piece of ‘thing’ that you buy at the supermarket suddenly takes on a different character. I didn’t eat meat or poultry after that day. I still eat a bit of fish. My partner, Johan, says to me ‘You don’t think the fish hurts a bit when it gets the hook?’ He’s right, of course, and I will probably end up vegetarian, maybe I’ll even go the full way and become a vegan! But I am where I am now. That demonstrates a journey.”

At lunchtime, vegan salads and sushi are arranged on tables outside the lecture theatre. There’s eager discussion about the speakers, which then turns into conversations about wider issues about animal welfare in New Zealand. In one circle of young lawyers and law students, I listen to debate about the government-supported initiative to make New Zealand predator free by 2050. One graduate, soon to be admitted, suggests that killing these so-called ‘predators’ (possums, rats and stoats) cannot be ethically justified and that nature should instead be allowed to run its course, even if this leads to the extinction of some native bird species. Others around him are more dubious. They say instead that there needs to be a more ethical, painless way of killing the introduced species that threaten native birds.

Just like these lunchtime conversations, the reasons it took so long for a conference of this kind to take place are complicated. Rodriguez Ferrere suggests that in part, it may be to do with the strength of New Zealand’s animal welfare legislation – if the law itself is already sophisticated and progressive, that can slow the momentum for urgent action and discussion in the animal law area. He also suggests the slowness may be because our economy depends largely on the use of animals in agriculture.

However, Rodriguez Ferrere does point out that in the last few years there has been a wider response and critique of the dairy industry and its corporatisation in New Zealand. Dairy farming, he argues, has shifted “from the original idea of an owner-operated farm with a few dairy cows making milk for the community, to an industrialised operation that seemingly happens overnight with significant environmental consequences. And while that hasn’t yet translated into concern for animals per se [...] people's demands for more transparency have influenced wider ideas about why [there is] a lack of oversight and regulation.”

Kirby also reflects on New Zealand’s journey with animal law. He says that the government has taken steps along the journey by enacting the Animal Welfare Act 1999 and the Animal Welfare Amendment Act 2015, which recognises that animals are sentient beings. “It started with recognising basic rights... But once you start to recognise sentience, which is something that is shared with human beings, then you have progressed a bit further and you are going to begin to ask yourself if [animals] are sentient, is it right that sows should be in very close confines and not be allowed to turn, to scratch themselves, or do all the other behaviours that are natural to a female pig? Is it right that a chicken, a most sociable animal, has to sit all day, all night on the equivalent of an A4 page of paper? Once you ask those questions, then you are propelled into a demand for action and that is where I am now. I’m at this conference, with Dame Jane Goodall and others who say acknowledging sentience on a piece of paper called an Act of Parliament is one thing, but working out what the consequences of that are for law, policy, education and our human empathy is another thing. We are increasingly going to be confronted with the other.”

Animal law and our attitudes towards animals involve an interaction between numerous and varied concepts and values. Animal law is science-based, environmentally-conscious and health-conscious. It stems from concern about mass industrialisation and factory farming, though general public awareness of animal law has heightened dramatically as more video and photographic documentation of animal abuse and devastating farming conditions comes to the surface.

But animal law is also emotional. It is tied into issues of privilege, class, race, age and gender. It is an area of contradiction – recently evident in New Zealand’s Court of Appeal decision involving Noel Piraka Erickson, who horrendously abused bobby calves while working as a slaughterman and was initially convicted on 10 charges of cruelty or ill treatment of an animal and eventually sentenced to two and a half years jail. His defence lawyer argued that Erickson, inadequately trained and supervised, had had his actions condoned and directed by slaughterhouse management.

On appeal of the sentence, The Court of Appeal found Erickson had been placed in a “deeply invidious situation" by his employers, and that also noted that the “rational differences” between agricultural animals and companion animals must be acknowledged. Though the Court was clear the fact that these were calves and not puppies didn’t act as a mitigating factor, it remains apparent that in the context of our society, abuse against one is not the same as abuse against the other.

The day after the conference, I travel to visit my dad who lives in the countryside. He has never held strong emotional connections towards animals. When Dad was nine years old he raised and cared for a calf called Lady Penelope and the year after, another called Emma Peel. He later worked on farms as a holiday job. I’ve been looking forward to telling him about the conference, and expecting some eyebrow-raising.

Dad cuts me short. Without saying anything to anyone, he’s been trialling a vegan diet for a week. He has replaced full-fat milk with coconut milk, purchased a non-dairy mozzarella along with several 1kg bags of lentils and kidney beans. He tells me how he’s just watched the documentary What the Health, made by Kip Andersen and Keegan Kuhn, the filmmakers behind Cowspiracy. The visual evidence of how animals are treated in factory farms in the United States and the discussions on meat and dairy products’ effects on health had disturbed him deeply. While a set of circumstances had aligned on a national scale for the first animal law conference to be held in New Zealand, at my dad’s home another set of circumstances had aligned for him to overhaul his diet. The NZALA conference is a big step and my dad’s new diet is a small one – but they’re both on the same path.Header image: Nicolai Fechin, 'Slaughterhouse', 1919