Sonic Shadows and Personal Mavericks: Ten Composers Who've Shaped My Work

SOUNZ Contemporary Award winner Alex Taylor shares ten of the composers who have shaped his music.

The feeling of music getting into your bones, your blood, your every movement, is something you don't easily forget. One of the most vivid memories I have is of sitting on the Auckland Town Hall stage playing Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony. The whole orchestra bent to the will of this exhausting, creaking, terminal music, and somehow this crystalline clarity in the eye of the orchestral maelstrom. Sweat dripping from the conductor's nose, cellists frowning in intense concentration, percussionists taut, ready to spring. I was totally riveted, all of my energy channeled into these strange sounds; I was actually shaking at the end of the performance. It reminded me how music is not just sonic, but also physical, emotional, even spiritual.

I have always found music an exciting, invigorating thing. Listening, playing, composing, even writing about music. Emotionally my musical connections are as diverse as early Split Enz and late Thelonious Monk, muscular Beethoven and sparkling Ravel. I value music that gets hold of me, music that provokes a visceral, emotional reaction. For me classical music is not so much an entertainment as an engagement; it requires a certain commitment from the listener. That's not to say it's only accessible to the educated ear. All one needs is a commitment to the sounds, a willingness to follow the sculpting and crafting of sonic shapes through time. My favourite composers are those that treat music not as a code to be understood, not as language, but as an organisation and transformation of sound in the most expressive and gripping ways.

Surveys of any sort are problematic. Here follows a sort of top 10 – composers I believe have shaped my music in some way, perhaps aesthetically but also conceptually – composers whose music has provoked me to reflect on sounds and time and space. I have chosen to focus on composers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, composers that are most immediate to my own musical concerns. So as much as I love and respect the music of Beethoven and Tchaikovsky and Ravel and many others, I can't claim that my own work bears much resemblance to the standard repertoire. That is a list for another day. This list is not chronological, but it journeys from nineteenth-century New England to twenty-first century New Zealand, via Nazi Germany, Stanley Kubrick and feminist ritual. Although this is merely a personal selection, I hope there is something for every committed listener here.

Charles Ives

Charles Ives conceived of music more realistically than anyone before him - music like the world, with its disparate elements, constantly moving in and out of synchronicity and sympathy. Ives's layering of distinct harmonic and rhythmic languages created some of the most bewildering and complex music of the twentieth century. Yet his compositions have an unmistakeable spirituality that is equal to Mahler or Beethoven - but with all the discomfiting vagaries, conflicts and humour of real life.

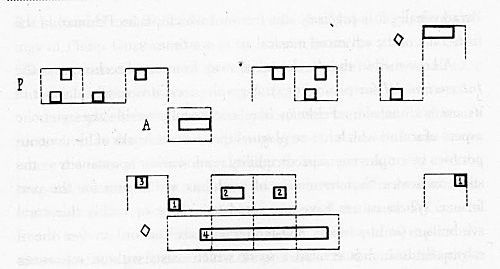

For my money the best way into Ives, so to speak, is The Unanswered Question, a work scored for three spatially independent instrumental groups: a bed of static, luminous strings; a restless, questioning pack of woodwinds; and the lone voice of a trumpet, whose poignant repeated solo is one of my favourite tunes in music.

If you can get past the fact that Ives was an insurance executive for most of his life, you may notice not only does he have a local doppelganger in poet Denys Trussel (the hats!), his music is also endlessly frustrating, stimulating and rewarding. A maverick worth getting to know.

Morton Feldman

Another American maverick, Morton Feldman's music inhabits a space at the very edge of silence and audibility. A truly minimal composer, Feldman explored the most subtle and intricate possibilities of very limited musical material, often over incredibly long spans of time. His longest work, String Quartet II, typically lasts over six hours, during which Feldman imagined his audience coming and going, reclining, listening, sleeping, meditating and moving in and out of concentration and awareness. Listening to a work of Feldman one quickly becomes aware of the tiniest sounds and subtlest variations of gesture; unlike the “classic” minimalists that followed him, Feldman – to my ears at least – is never boring. Where many of Philip Glass's longest indulgences could be summarized in a handful of relentlessly driving chord changes, Feldman's tapestries are minutely detailed with flawed symmetries and a supple, delicate sense of motion.

As well as fostering a close association (and perhaps a shared aesthetic) with many of the abstract expressionists – de Kooning, Pollock, Guston and company – Feldman collaborated with writer Samuel Beckett on an opera, Neither, a tense, prickly work that explores our perception of time and stasis. The music here so aptly reinforces and interacts with the endless dread of Beckett; to me Beckett is never more clear or eerie than when the words explore their own temporality.

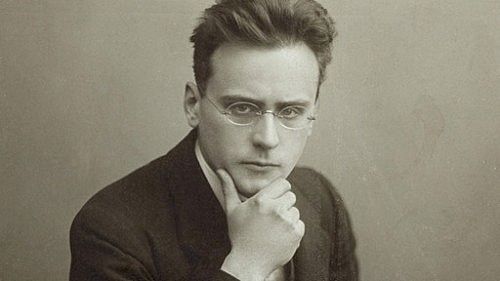

Anton Webern

In scale Morton Feldman and Anton Webern could not be more different composers; many entire movements of Webern run for less than a minute each. However Webern was one of Feldman's idols, a musical sculptor of incredible clarity and precision, never wasting a note or keeping his audience a second too long. Although reactionary types tend to label his music as dry or even “academic” (whatever that means) – generally because non-tonal kinds of music have been treated rather badly by orchestras and other large music institutions – I would say Webern is one of the most expressive, dramatic, fragile composers I know. And although his output tends toward the miniature rather the mammoth, it is a veritable treasure trove of not only beautifully crafted contours and sonorities, but also precarious and dazzling feats of musical acrobatics.

An introduction to Webern might be the tantalisingly brief, if prosaically titled Six Bagatelles for String Quartet, for me like a miniature opera, with traces of Romantic intensity but also moments of icy austerity, looking backwards to Mahler and forwards to the bare soundscapes of composers like Feldman and Christian Wolff. Textures wax and wane instantly, climaxes collapsing into pools of static noise or ethereal harmonics. Listen once and you might be bewildered; listen twice and you'll be an addict.

Anthony Watson

Just as Webern's music is often overshadowed by the more ambitious Arnold Schoenberg or the more Romantic Alban Berg – both of whom could easily have made this list in addition to Webern – Anthony Watson has been largely overshadowed by Douglas Lilburn here in New Zealand. Like Webern, Watson's output was relatively tiny, but within it are works of uncompromising, abrasive brilliance. Watson's music seems distanced from the New Zealand mainstream of the time: rather than being lyrical, nostalgic and naturalistic, this music is sharp, brittle and difficult. Watson too was difficult; the painter Michael Smither described Anthony Watson thus: “he was pedantic, spiky, intolerant, abusive and at times quite crazy with drink and depression, yet he was one of the most sympathetic, real men I have ever met, and I loved him.”

Despite the challenging, confronting nature of the music, there are also elements of the familiar: adrenalin-soaked rhythms reminiscent of Bartok; glassy stasis that at times feels like Shostakovich at his most chilling; Webern-like melodies of angular beauty.

Very little of Watson's music exists online but most of his works have been recorded on CD. An extract of his seminal Prelude and Allegro for Strings can be heard here as part of a wider survey of New Zealand composition I compiled in 2012. His excellent string quartets are also available on Spotify.

Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire

Alban Berg: Lyric Suite

Douglas Lilburn: Symphony no. 3

György Ligeti

György Ligeti's music is too diverse, too full of idiosyncrasy and artistry, to be summarised adequately in a handful of words. From the spidery, nightmarish webs of Atmosphères and Apparitions to the hyper-mechanical Chamber Concerto or the sweeping lyric of the Viola Sonata, each work employs its own distinctive language and yet remains unmistakably Ligeti. His music is probably most well-known for being used in Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey – without Ligeti's permission. Kubrick ditched the original music (commissioned specifically for the film) in favour of existing recordings of classic and contemporary repertoire – the majestic bombast of Strauss's Zarathustra alongside the dense, crawling vocal textures of Ligeti's Requiem.

Although the instrumental finesse and spatial interplay of Ligeti's orchestral music is really best experienced live, good recordings of most of his catalogue are relatively easy to find online. Here is the mind-bending Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet, pushing the five instrumentalists to their outermost limits in a highly concentrated acoustic barrage.

Strauss: Also Sprach Zarathustra

Conlon Nancarrow

Ligeti's fearsomely difficult piano etudes, performed recently in Auckland by Chinese virtuoso Xiang Zou, were in a large part inspired by the music of communist exile and composing hermit Conlon Nancarrow. Nancarrow's rhythmic ideas were so complex that he gave up entirely on writing music for human performers. His player piano studies, all coruscating displays of mechanical virtuosity, are inflected with the grooves of ragtime and stride piano, but impossibly layered in strata of different gradients and intensity. Nancarrow is something like the love-child of Charles Ives and Art Tatum. Forget 60s psychedelic rock – this is the essential musical trip.

For those interested in the link between Ligeti and Nancarrow, I've included a study of Nancarrow's and an etude of Ligeti's for comparison – the material is uncannily similar, although each composer's treatment is quite distinctive.

Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano no. 37

(c.f. Ligeti Cordes a vide)

Gerard Grisey

Where Nancarrow offers an aesthetic of radical complexity, a maelstrom of intersecting and conflicting rhythms, Gerard Grisey's music is conceptually very simple: he focussed on what sounds are made up of, their tone colour, their harmonic spectra.

Partiels takes as a starting point a spectral analysis of a low trombone note, whose constituent frequencies, intensities and contours are then re-orchestrated for eighteen instruments to imitate or shadow the sound of the trombone. This technique of instrumental synthesis was developed from electronic music and has since been utilised and expanded by numerous composers, including Kaija Saariaho, Jukka Tiensuu and Magnus Lindberg. Partiels (which translates as “partials”, the constituent frequencies of a harmonic sound; or in other words, the “overtones” of the harmonic series) is part of a larger work, Grisey's masterpiece Les Espaces Acoustiques, which grows from a solo viola to a huge orchestra, each movement exploring a particular concept of Grisey's unifying idea of music, his theory of everything, in a sense.

Kaija Saariaho: Verblendungen

Samuel Holloway

Perhaps it seems a strange, circuitous route to arrive at Auckland composer Samuel Holloway via Grisey. But both composers share a concern with process and a refined, limited means of expression, if not always a similar aesthetic. Like Grisey, Holloway deals with sound on a fundamental, conceptual level, and his work often has more in common with contemporary art practice than the music of his fellow composers. This music is concerned with our perception of shapes, the tension between physical act and aural result, and the underlying structures and processes of music.

In Sillage, Holloway superimposes a number of different structures over a central, simple process – the gradual detuning of a bowed acoustic guitar. In contrast with much of Holloway's earlier music – fastidiously notated and often extremely difficult to perform – Sillage (French for the wake left by passing ships) is rather free and fluid, almost viscous, resin-like in its various elements clinging together. The ensemble colours, highlights, bleeds out of the bowed guitar, building a luminous haze of pitch and noise.

Eve de Castro-Robinson

Eve de Castro-Robinson in many ways could not be a more different composer from Samuel Holloway (although she taught him at Auckland University), but both share a connection with French music. Grisey's central interest in colour grows out of a long French tradition – Saint-Saens, Ravel, Messiaen, Dutilleux, and many others. The French aesthetic, if one can ever pin down such a thing, is often more interested in the subtle gradations of tone colour than the overarching teleological structures of the Germanic musical tradition. Where Mahler wanted music that encompassed the world, Ravel was quite content with his own sparkly little corner of it.

de Castro-Robinson's music has something of this colouristic language, combined with a strong, almost overwhelming sense of gesture and ritual. Her music also draws on nature as a musical resource, in particular all manner of birdsong, from mellifluous tunes to cacophonous interjections. However there is much more to de Castro-Robinson's multifarious and unique output than birdsong. Urban landscapes, popular culture and personal reflection all play a part in her music-making. Commemoration celebrates the life of Gerard Crotty, a friend and fellow New Zealand composer who died at the age of 30. This work shows de Castro-Robinson's sensitivity to the solo instrumental line, crafted simply but incredibly powerfully here.

Messiaen: Oiseaux Exotiques

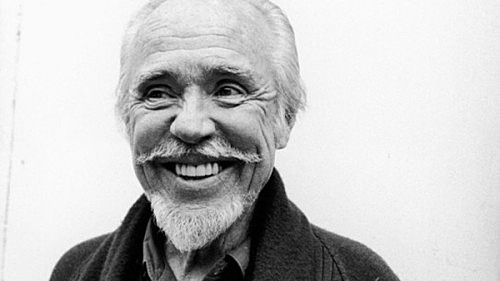

Annea Lockwood

Although Annea Lockwood is most notorious for her Piano Burnings – in which decrepit, unwanted pianos are set alight, erupting in a gradual cacophony of snapping metal, wood and flame – her entire catalogue is ambitious and innovative, if not always so visceral and violent. Lockwood's practice often intersects with natural and environmental sounds – water, stones, glass, wind – and with personal or communal ritual. Some of her work might even be called primitive in its simplicity of expression – fingers on a drum, the purring of a tiger – but one feels that pedantic, craftsmanly detail would only obscure the strength and mystique that these gestures contain.

In this short piece for solo snare drum, Lockwood explores not only the wealth of sounds such a drum can produce, but also re-situates it in a context of ritual. Gone is the incisive military pulse we expect, replaced with fluttering and groaning, circularity and ellipsis.

Lockwood: Amazonia Dreaming