Somewhere We Can Live

In the past two-and-a-half years, two Wellington-based writers have published novels placing an earthquake in their home city. Simon Gennard writes about reading - and living with - imagined disaster.

In the past two-and-a-half years, two Wellington-based writers have published novels placing an earthquake in their home city. Simon Gennard writes about reading - and living with - imagined disaster

We try not to talk about the future. We’re usually interrupted when we do. We talk about buildings, and sometimes falling. We joke about vast stretches of desert and underwater cities and, less often, rubble, and the probability of us not having children. We – my friends and I – talk about Wellington like we might one day own it, or some of it. Or at least find ourselves a secure tenancy arrangement. Something small, dryish, on the right side of a hill.

The futures we plan are futures jolted by something awful. If I am at work when it happens, I will curse our heritage: slabs of brick and stone, things that seem to make so much sense elsewhere. If I am on The Terrace, or Ghuznee St above the motorway, I will hold on to nothing. If I am at home, I will wait. There is an imaginary line that runs through the land close to that harbour. It is red. The line is lowered expectations: a place for those least likely to survive in the event of a tsunami. Behind the line, heading towards the hills, is relative safety. I work in the red line, and I have planned to go to the roof and hope for the best. My building is a gallery and the walls change every three months. I can never remember which walls are and aren’t connected to the foundation. Expensive, heavy things are drilled into them and they crack easily. I keep having to rethink where to cower and how to get there. I don’t think the building wishes us well.

Christchurch feels both distant and very close. Commemorations have a habit of doing that. As easy as it is, five years on, to allow ourselves not to think about it, last month’s anniversary reminds us that for those who live there, it doesn’t end so easily. It never felt particularly close to me. I've never actually been to Christchurch and I don't like admitting it. I like to think that my capacity for empathy extends towards understanding the suffering of those who lost homes, loved ones, any feeling of security. What I struggle with is the landscape; not really knowing what the place once looked like before makes placing pictures of ruin difficult. Not being able to imagine what the city looks like whole makes it difficult to think about putting it back together again.

I don't know if it works the other way around. I have lived in Wellington for most of my life. Most of what I think about, when I’m not thinking about other things, has to do with the city’s demise. There is always an awkward, ghoulish appeal to translating ruin. Putting it somewhere else, another place we know and live. This may help explain why, in the last two years, two Wellington-based writers have published novels which take as their conceit the possibility of an earthquake in their home city. I don’t know if it’s an exercise in trying to feel the pain of others, or a symptom of a certain sway towards the dystopian. That is to say, a cocktail of casualised labour, repeated and gradually worsening financial collapse, and our inevitable environmental comeuppance produces a profound mistrust in the continuity of the present. It appeals, though. I delight in shock, in that dull ringing after the event, before a promise of recovery can be made, before the why and how of what happened can be articulated. Both books, in peculiar ways, delivered this to me gracefully.

There is always an awkward, ghoulish appeal to translating ruin. Putting it somewhere else, another place we know and live.

Pip Adam’s I’m Working on a Building reveals itself backwards. It begins with a strange act of national grief; hubris as a wound-licking strategy. On a West Coast beach in Tai Poutini National Park, a replica of the tallest building in the world, Dubai’s Burj al Khalifa, is being built. It’s 2019, several years after a massive earthquake has destroyed Wellington. We learn that the novel’s protagonist, Catherine, an engineer, is “sure of herself, angry at everything, more qualified than anyone.” I adore her for that. I adore her for her frustration, her vagueness, for the kind of deferral that propels the novel; the kinds of conversations that happen of both great and no consequence, recalled without any real distinction between the two. Catherine is not easy to love and does not love easily. The problem may be one of identification, of not knowing and feeling how others feel, or it may be something else. There is a moment, late in the book, when Catherine is a child, unaware that she is lost in Centre Pompidou in Paris, unaware that her family are looking for her. “She treated everyone as if they were made of the same material – sister, teacher, mother, stranger.” Nuance seems to hit a blockade before reaching Catherine. We find ourselves filling in gaps, piecing things together from what we know of how events turn out. Catherine is employed on the Burj project on the basis of this ambiguity, aware of its gravity, but none of its detail, The narrator recalls an early meeting between Catherine and her employers, “They talked about the job, how they couldn’t give her many details about the job due to the nature of the job.”

We learn that friends have died. That other friends will marry. Others are coming and going and redecorating. We learn to think of the Wellington earthquake as both a site of trauma and a minor interruption. As we read on, trauma gets disarticulated. It gets both closer and more difficult to speak of. Its enormity isn’t quite revealed until a third of the way through. We are with Donna, a character who up until this point has merited only a passing mention. Donna was running around Oriental Bay, as she often did during her lunch breaks, and then suddenly she wasn’t running anymore.

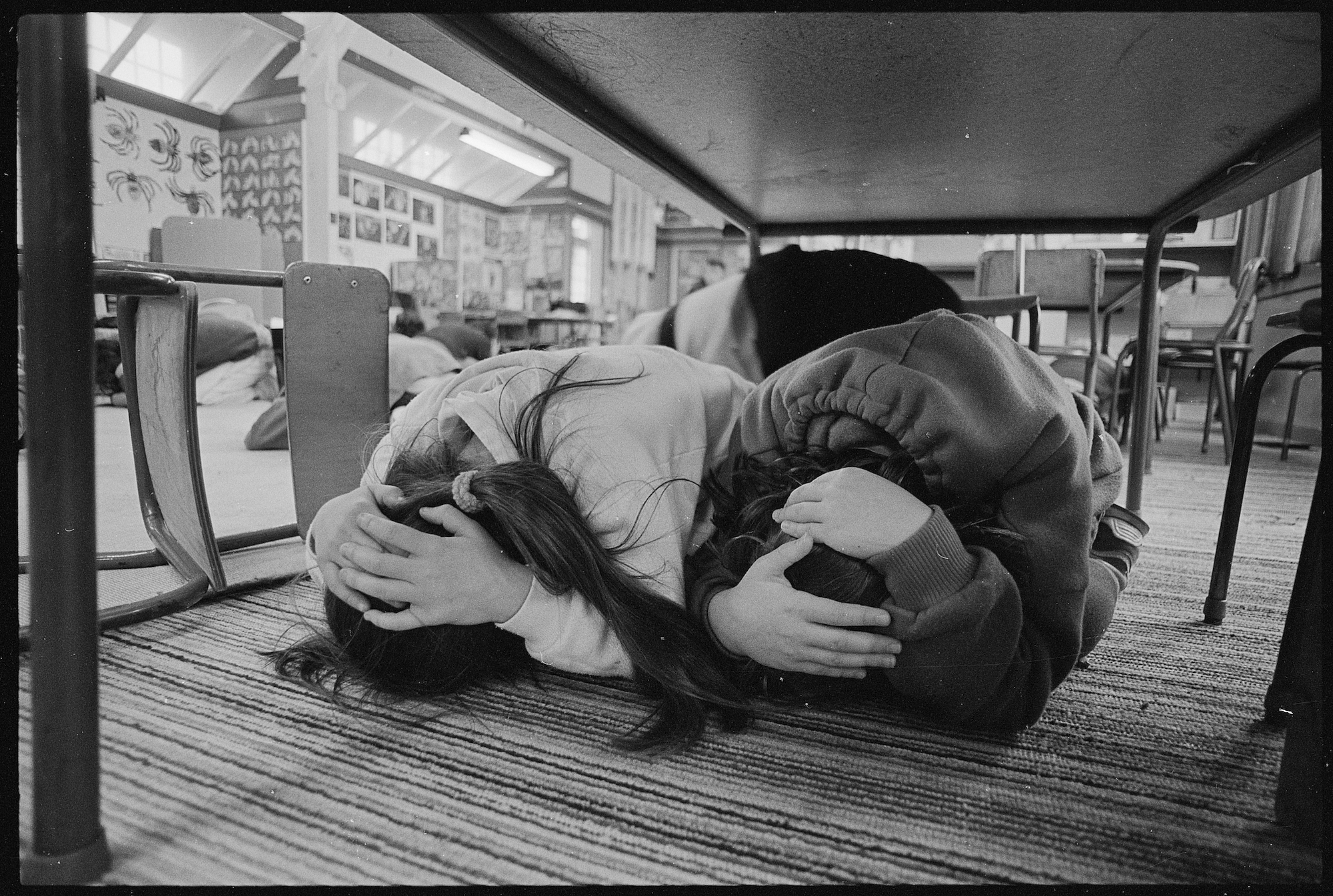

There are only so many ways to write about the routine interrupted; about what shock does to the body, how limbs are accounted for before those present make their way to safety, how things are placed into some preliminary order before sense can be made. The language of disaster is familiar, even, especially when it’s said in a New Zealand accent. I’m thinking about singing along with Te Papa’s earthquake house, about friends of mine who have described in detail where they were, what they were doing, who they were with, in Christchurch on the 22nd February 2011, about the specified date and time each year, when people will cheerfully fulfil their civic duty to spend several minutes crouched beneath a table or desk.

It’s this knowingness, this fatigue with scripted recovery, that makes the first half of Hamish Clayton’s The Pale North difficult. The novel’s narrator, Gabriel North, writes in prose that is dense and thick and saccharin. Ruined buildings, half remembered, drift “free of the city… a barge afloat in a dream,” women are “statues,” or “sibyls,” or “dryads,” or “creatures born of classical myth.” All of these are lifted from a single page in the first chapter.

The Pale North, it turns out, is less a dystopia of the author’s imagining than it is a record of a protagonist writing a dystopia into being. Halfway through the novel, we learn that what we have read of Wellington in ruins belongs to a manuscript discovered by a historian, Simon Petherick, in the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt. Knowing this, the novel quickly becomes a kind of excavation, a clawing at an event that refuses to yield to what we expect, or desire, to find. North’s sickly prose becomes something of a caution against treating trauma as a fertile site for redemption. It’s a knowing, brooding wistfulness that may have had currency once, but seems artificial in its sincerity now.

North’s sickly prose becomes something of a caution against treating trauma as a fertile site for redemption.

Locating the novels in time becomes tricky, especially if I’m trying to talk about them together. Adam’s belongs to an imagined future; the Burj replica is nearing completion in 2019, the earthquake having happened several years before, on some unspecified date between 2013 and then. Gabriel North’s manuscript is dated 1998 and discovered by Petherick sometime in 2014. Everything I’ve been taught about demarcating the boundary between text and reality falls apart. Narrators describe streets I walk down almost every day and I find myself wanting to interrupt, like when North’s narrator details walking down the Allenby steps: “I loved the fall to earth as you followed those steps all the way down, and then the sharp turn to the right for the final few flights, creating that ledge of air and the gentle float downwards past the Gothic spires of Saint Mary of the Angels.” The church is usually obscured by trees, or a fence, or scaffolding. More often than not, any “gentle float” is interrupted by greasy backpackers sunning themselves, or drivers inexplicably tooting at you for walking in the middle of the road. But this is not my Wellington, and I don’t live in the late 1990s.

Maybe I’m warmer towards Petherick because he asks the same questions I do. And, like myself, he finds himself unable to answer them. Petherick, more than anything else, seems to be interested in questions of ownership, in how a reader might go about claiming or disavowing a text in order to arrive at meaning. “We need only,” he writes close to the end of the novel, “attend to ways of reading.” And yet this admission is positioned after a sustained effort at piecing together a coherent rendering of Gabriel North; of trying to figure out who he is or was and why he would invent an earthquake. Petherick pieces together where North was at particular moments during the last two decades, who he was with, what he did and how he did it, while, all along, insisting upon North’s intangibility.

Petherick, like me, is interested in how and why a writer would come to document a speculative site of ruin. He surmises, from North’s diaries, that the Wellington described in the novel is not an allegory for Christchurch, but a project begun a decade prior. Beyond that, Petherick is unable to attribute North’s disaster to anything more. The question of ownership, then, seems to spill outwards, applicable not only in reference to what we do with texts, but what we might claim, or disavow, or imagine by inhabiting a time and place. When I feel myself protesting North’s rendering of the Allenby steps, I feel my grip on Wellington loosen; I’m forced to acknowledge the possibility of someone else (real or fictional) being able to know and describe the place I live differently or better than I can. Owning is holding, and it is also poking and throbbing and ripping apart. Intimacy with a time and place doesn’t just limit itself to being able to describe what the time and place looks like, it also means being able to manipulate it, being able to turn it into something else, being able to imagine a future in which it is different. Living in Wellington, then, means being able to elaborately describe it in ruins.

Living in Wellington, then, means being able to elaborately describe it in ruins.

In both novels, effects seem to misalign with causes. Whatever paltry explanations characters offer themselves seem cruel and inadequate. We know that plates are constantly rubbing against each other, that beneath the surface of the Earth, the ground is in constant motion, that sometimes pressure has to be released. We know that some buildings are more vulnerable than others. And yet we never come close to understanding why things happen. If, in reading I’m Working on a Building backwards, we hope to uncover the origin of Catherine’s abrasiveness, the answers offered seem lacking. Catherine was at the top of a building being built during the earthquake. She was examining a small crack, with two other engineers from her firm, both of whom are killed when the building collapses. From a pile of rubble, she chastises herself for not insisting on going there alone, “If she’d been different,” Catherine thinks to herself, “more certain, they wouldn’t have been here.” Such a concession seems both too easy and profoundly seductive as a clarification of character. It seems simply not enough that Catherine, the way she holds herself, her spite, her brilliance, would be the sum of her failures.

Near the end of the book Catherine is a Cool Teen. Angry, drunk, kind of homeless. In some ways it seems not only a reversal of the third act’s motion towards redemption, but a way of rendering redemption, upon which Western narrative is built, dubious as a possibility. Were we to flip the narrative, the Burj replica – and with it Catherine’s professional success – would signal a happy, satisfying ending; cause and effect wrapped up but not too neatly. Yet we know that this story doesn’t really piece together like that. At one point one contractor remarks to another, “The Burj Khalifa isn’t the tallest building anymore…. The Kingdom Tower opened overnight.” It’s a strange, flatly spoken aside, that seems to have no bearing on anyone’s relation to the project, and, for the reader who has heard over the last half decade of recovery resources being allocated to strange, perhaps less than urgent place, the statement seems only to render it more absurd, and weirdly plausible. The lines between cause and effect are hazy. Sometimes, particular routes of reasoning seem too easy to be followed seriously. Sometimes, delving into the past summons forth circumstantial evidence as much as it may seem to provide explanations for events, sometimes things just happen, by happy or miserable accident.

Neither novel positions itself as a speculative projection of a future Wellington. And neither, really, seems interested in describing nor investing in ways people can try and survive in devastating circumstances. The worst has already happened. And though the trajectories we follow seem unmistakably shaken, we are left with the feeling that they were never very stable to begin with. It might be possible, then, to say that both novels are products of a specific locality; are born from whatever energy is exerted in occupying a specific time and place, and that this is a time and place in which a small apocalypse has been, and keeps being, imagined, modelled, and planned for.

Both novels are products of a specific locality... this is a time and place in which a small apocalypse has been, and keeps being, imagined, modelled, and planned for.

A psychologist once told me to think about anxiety as anticipated grief, as a state of being that imagines reality as the sum of worst possible outcomes. Anxiety seizes the future, making continuity seem inconvenient, irrelevant, or unthinkable. Attempting to think of the future under the overwhelming presence of disaster is always an exercise in finding oneself stuck before this disaster, unable to move through or around it. We might be able to develop any number of possibilities for thriving now, soon, or eventually, and we might picture them as leaps forward, or as a sprawling multitude, but catastrophe always seems to catch up – it could be in the form of an alternate 1998, or on an unspecified date between now and 2019.

As Catherine’s two friends plummet from the top of their building, we are transported to an otherworldly realm, some kind of flashback leading to the gates of heaven. These two characters are the only two in the novel who seem in possession of anything close to fulfilment, the only two who seem to bear any affection for each other, and yet are kept apart by less-than-ideal circumstances, small choices made long ago. One character is taken to the bush, at least a decade before, to an ambivalent memory of the pair together. “As we walked that day you told me sometimes you imagine both of us are dead, and as we walked I imagined you imagining we are dead, and this is what it looked like then and, to my surprise, this is exactly what it looks like now.” This small observation, easily lost among a timeline that keeps collapsing and putting itself back together, seems to claw at the novel’s uncanniness. It’s that point at which one imagining meets another, the moment when expectations are met, when the anticipation of something comes into fruition. Living here is an exercise both in imagining disaster, and in imagining others imagining disaster. In a way it might be read as a sigh of relief, a way of finally being able to call something real, the world finally giving way to how it keeps being conjured. So we could treat both of these novels as another instance of this anticipation, another pair, albeit perhaps more elaborately realised than many, of the kinds of contingencies that get played out daily in the minds of those trying to live here.

Header image: School earthquake drill by Mark Coote, Evening Post newspaper. Ref: EP/1991/1627/25-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.