Solo Tangi and a Bag of Frozen Peas

Ngahuia Harrison on the immensity of Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art.

On the day that Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art opened, I went home for a rest in between the morning and evening formalities. I had a headache from all the cortisol that had been kicking around since dawn. I lay on the couch with a bag of peas on my head. And for a moment, I wept. At the time, I couldn’t tell you what the tears were or weren’t for; like the headache, they were just there.

In part, it had something to do with seeing my own work sitting amongst the 110 artists included in the show. Artists I look up to, that I have been greatly influenced by, like Rachael Rakena and Merata Mita. Artists who are whānau, mentors and friends. Each time I return to Toi Tū Toi Ora, however, the reasons for my solo tangi into frozen peas become clearer. I have returned to the show five times, in large part because returning is what this show demands of you.

The morning blessing drew a significant crowd. Many of our Ngātiwai whānau had travelled to support those of us in the exhibition. This pull of whānau was buzzing through everyone, as well as the push of history and redress. This was about time. And it was about time; all of a sudden, we were underway. Led by Ngāti Whātua, we bottlenecked through the gallery entrance, reception and exhibition threshold.

Then everything was dark. ‘Te Kore’, often translated as ‘the nothingness’ or ‘void’, is also a space of great generative potential. Moana Nepia writes, “Te Kore, as a concept integral to Māori thinking about creativity, articulates the extreme limits of imagination, the origins of everything, including human existence.” Or as Kura Te Waru Rewiri painted in 1986, There is more in Te Kore.

Returning is what this show demands of you

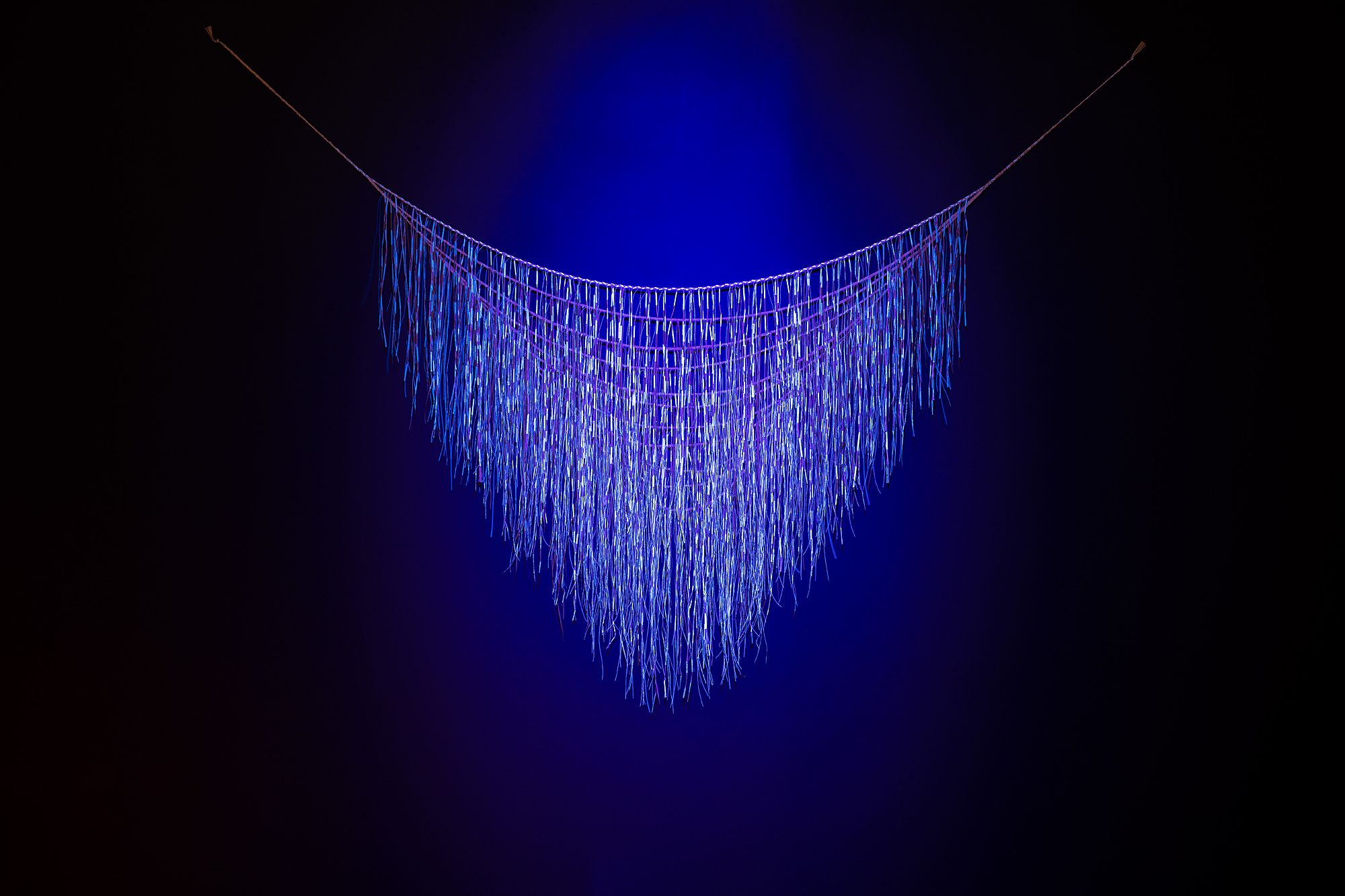

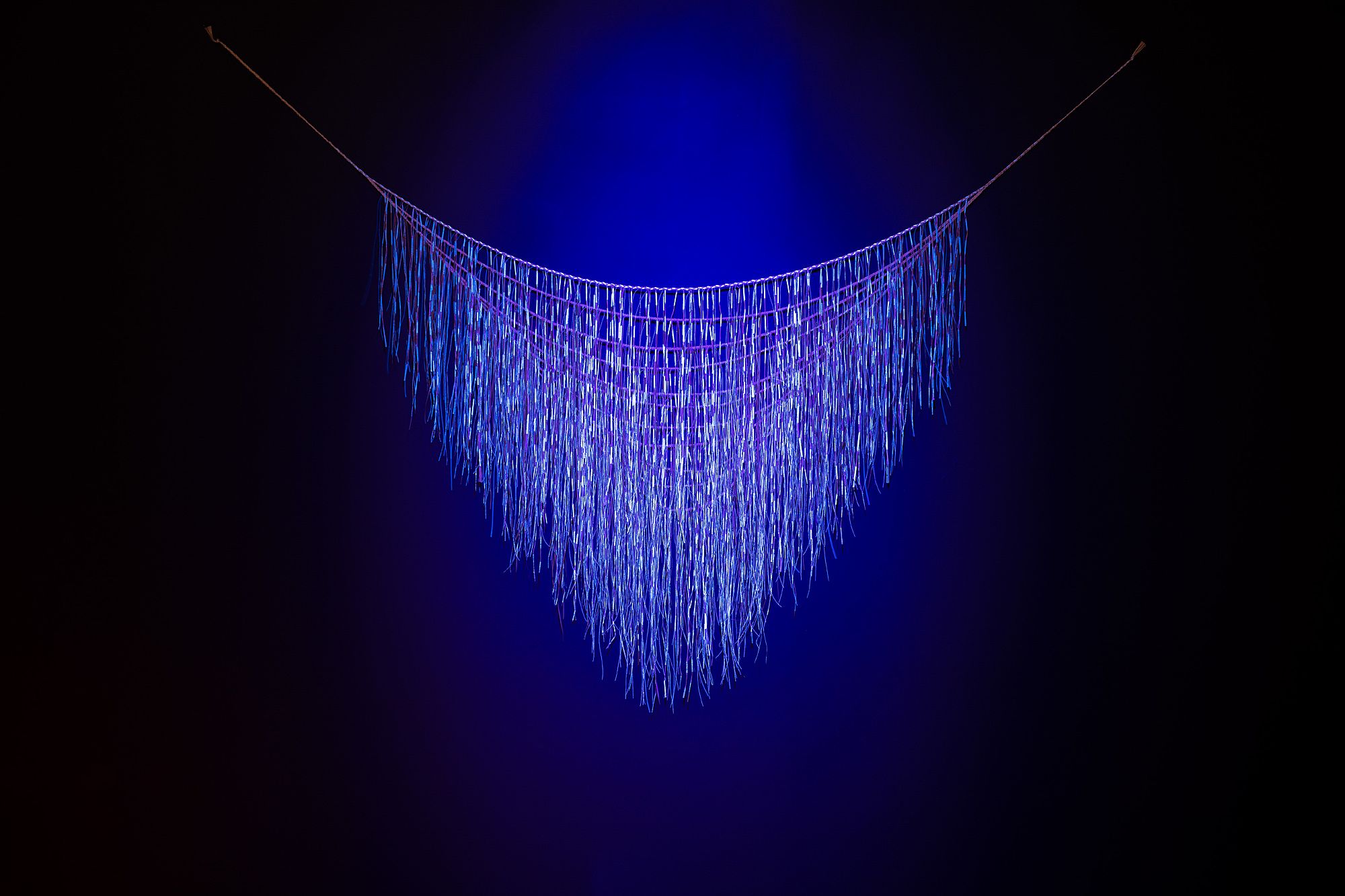

And of course, there is. There is Peter Robinson’s Universe descending upon us from the ceiling. There is Bob Jahnke’s Whenua Kore infinitely swallowing Reuben Patterson’s Te Pūtahitanga ō Rehua. A glint on the far wall hints at a darker shade of black, the ‘redemptive’ darkness of Ralph Hotere’s Black painting. Rounding the corner, Maureen Lander plays with our eyes by way of a hologram-like presentation of her work Wai o te Marama. A piupiu of harakeke, muka and nylon realises Lander’s vision of water ‘lit by the moon’. We have entered ‘Te Pō.’

Maureen Lander, Wai o te Marama, 2004.

After the night, we move into the parting of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. From here, like the children that split them apart, we too are led into the world of light, leaving behind Lisa Reihana’s atua-sized depiction of the lovers’ separation. The pace at the opening was set by Ngāti Whātua, moving quickly up three floors before the sun appeared. The ground floor offers ideas of the unearthly – ‘Ira Atua’. Māori philosophical underpinnings, our cosmogony narratives, reverence for the divinities, and finally turning into the world of light and day. From here, we ascend the upper floors from the celestial to the terrestrial – ‘Ira Tangata’.

In the peopled world, ‘Ira Tangata’, we are asked to consider politics and gender, provocateurs and prophets. ‘Tikanga Ora, Tikanga Toitū’ explores the persistence and evolution of traditional art forms. The adjacent spaces ‘Ngā Ao o te Ātārangi, o te Hanga, o te Whakaata,’ are occupied by artists exploring mātauranga Māori utilising modern media.

That first morning, we sailed through the spaces. Not taking in details like who is watched by Michael Parekōwhai’s Poorman, Beggarman, Thief, or what artworks are whispering to each other in the historical Mackelvie Gallery. How salient Ana Iti’s work is, recreating artefacts of the Land Wars in a Gallery that honours the name of Governor George Grey, the warmonger who invaded Waikato. In that pre-dawn moment, we were taking in something much larger that this exhibition has to offer. My friend Francis McWhannell described the feeling of “something much larger” on that day, “perhaps what is kept on the margins should really be the centre.”

Sandy Adsett, Puhoro, 2020.

In concluding, I return. Wandering through the gallery, I’m trying to think of a way to finish. But I can’t, and with every return I feel the same mixture of sadness and pride that I felt that first day with the frozen peas. On the stairs below what looks like large stained-glass windows, I take a seat beneath Sandy Adsett’s Puhoro. An appropriately reflective space, the vinyl kōwhaiwhai reflects Adsett’s mastery of colour across the atrium. Instead of a church organ I have the pleasure of Ben Tawhiti’s slide guitar drifting down from Nova Paul’s This is Not Dying. I realise there are no conclusions here because this really isn’t dying. This exhibit isn’t a full stop before another 20-year silence. This show is an open call, a perpetual return. Even the gaps in the exhibit indicate that this shouldn’t be ‘it’ for another couple of decades. There is much to be returned to, to be filled in, to be examined anew.

We have to keep returning. Real partnership, as guaranteed, is not a relationship you settle. Returns, like homecomings, can be joyful, but they can also be painful, and maybe they make you face things you wanted to leave behind. Toi Tū Toi Ora shows the necessity for Aotearoa to be reflected back to New Zealand. It shows the need to include Māori in honest ways, in vital ways – because we have things to teach you about who and where you are. Part of the teaching is about acknowledgement, which we are reminded to do on returning home. With that, here I give thanks to Nigel Borell.

Feature image: Maureen Lander, Wai o te Marama, 2004.