Slippery Questions: The Role of Ethics in Art

Melissa Laing asks what it means to create ethical art - and what role ethics have for an audience member.

It was around 8pm on the 8th of April in 2005 when I purposefully stepped over an invisible barrier at Artspace Sydney and, in doing so, administered an electric shock to the then 60-year-old performance artist Mike Parr. At the time, my reason for doing this could be summed up as this: Kingdom Come and/or Punch Holes In The Body Politic is a Mike Parr work. He wants to be shocked, and if we don’t shock him, the work doesn’t work. Looking back, I was putting the emphasis in the wrong place, determined to consummate the performative action, eager to realise the shock as the ultimate joining of me and him. But the work - which was responding to the practices of torture at Guantanamo Bay by enacting an empathetic self-torturing - was, in an echo of Stanley Milgram, a piece that revealed a shared, human willingness to obey instruction: even when those mean inflicting pain on another human. You could say it was an ethical moment, and I blew straight through it without pause. *

I didn’t pause until a number of years later.*

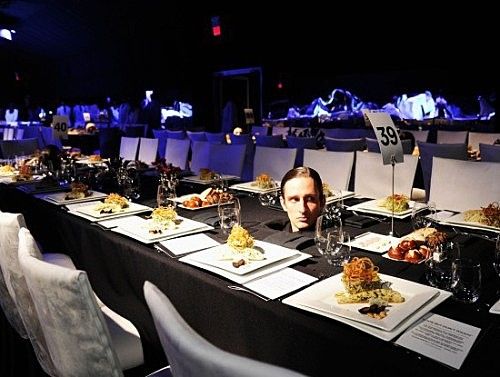

In 2011, Marina Abramovic choreographed a performance for a fundraising event at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. The piece required performers to endure potential physical harassment from gala attendees without complaint, while working for a payment which, given the projected hours of labour, came in under the American minimum wage:

They will be sitting on lazy susans under the table and slowly rotating and making eye contact with the donors/diners. Of course we were warned that we will not be able to leave to pee, etc. That the diners may try to feed us, give us drinks, fondle us under the table, etc but will be warned not to... The hours probably total 15 or more and the pay is $150 (plus a MOCA one year membership!!!)

Yvonne Rainer wrote an open letter to Abramovic in response:

Subjecting her performers to public humiliation at the hands of a bunch of frolicking donors is yet another example of the Museum’s callousness and greed and Ms Abramovic’s obliviousness to differences in context and some of the implications of transposing her own powerful performances to the bodies of others.”

We only need to look at the rise of organisations like Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) and a-n campaigning for fair payment for the arts to know that inadequate payment and exploitation in the arts is still prevalent. That this current advocacy echoes earlier campaigns in the 20th century for fair payment for creators demonstrates that the issue is systemic. At the time Rainer’s letter came out, I was conscious that I worked for an institution which had only recently implemented artist’s fees as a matter of routine, a change in policy from that of the previous director. Despite this being a positive step, we all recognised that - given the amount of work that goes into any show - the fee was a courtesy rather than an adequate wage.*

Later, in 2012, I really truly paused, and decided to think about this properly.*

And so the Performance Ethics Working Group came about as a research cluster, a line of enquiry, a thought provocation, a drawing together of people’s knowledge and a sharing of the same. It is an open group and a single person in a small room with a computer and an email connection. It is a social network gathering for discussion. It changes and aspires to change. It is just me and it is everyone.

The Performance Ethics Working Group works on the question of what ethics has to do with performance. It is a slippery question, with uncertain answers, partly because the word ethics is slippery, contested. The big name, old men of philosophy like Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Bentham, and Mill couldn’t agree whether ethics had to do with inherent virtues and moral character (virtue ethics), or duties and rules (deontology) or if it was determined by the consequences of actions (consequentialism). Later feminist and post-colonial thinkers rather accurately pointed out that all of these discussions emphasised traditionally masculine or western traits and social structures at the expense of other world views. Looking for other traditions of ethical thought I recently came across the following description in Stanford’s rather useful online Encyclopaedia of Philosophy:

ethical thought is centrally concerned with questions about how one ought to live: what goes into a worthwhile life, how to weigh duties toward family versus duties toward strangers, whether human nature is predisposed to be morally good or bad, how one ought to relate to the non-human world, the extent to which one ought to become involved in reforming the larger social and political structures of one's society, and how one ought to conduct oneself when in a position of influence or power.

We presume performance is ethical because it has the capacity to challenge the social and political structures of our world. But creating a performance with an ethical subject is not the same as being ethical in the production of the work, nor does the industry that the performance operates within necessarily support ethical positions. While society’s understandings of issues like labour relations, authorship, community agency and the specificity of cultural knowledge have changed, have we, in the performing arts, changed our methods to reflect this? Are we keeping up with best practices developed in other fields. or are we cruising along on a bolster of artistic autonomy, buttressing ourselves from true self reflection with the belief that we are ethical people?

We presume performance is ethical because it has the capacity to challenge the social and political structures of our world. But creating a performance with an ethical subject is not the same as being ethical in the production of the work

Having conducted 23 interviews with people participating in contemporary performance across theatre, dance and the visual arts, I’ve come to think that it's something in between. We’re negotiating the conflicting demands of the artwork, the ethical relationship to the communities the work is created within, and our need to care for the self constantly. Problematically, when we come up against ethical issues, ones which are often deeply embedded in the historical structures of how performance has been conceived of and made, we deal with them by ourselves, and we don’t talk about them in public. Sometimes its because talking about them would cost us our jobs or we think we handled it badly, other times its because we fear that talking about the difficulties inherent in the creation of work would detract from the reception of work. And so we continue, making it up in isolation as we go along. To try break down this isolation I compiled the 23 interviews into 9 podcasts which examine the complexity of these questions (listed below).

Problematically, when we come up against ethical issues, ones which are often deeply embedded in the historical structures of how performance has been conceived of and made, we deal with them by ourselves, and we don’t talk about them in public.

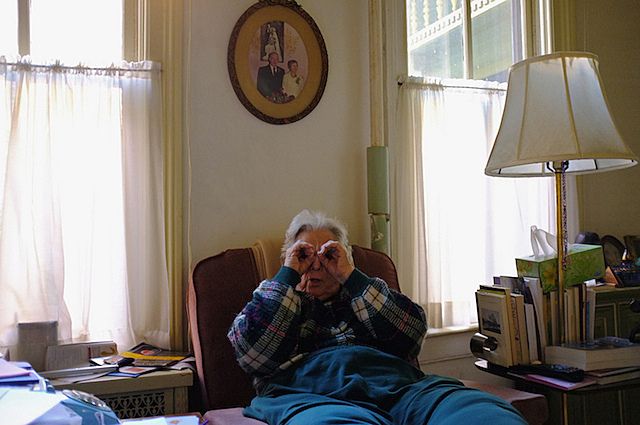

I soon realised I’d left something out of that first working group. Us as audience. The silent, or not so silent partner to performance. A second working group assembled on the last day of the Festival of Uncertainty at the Old Folks Association in early 2014. Its purpose was to ask ourselves not what we as creators want from audiences, but what we in our active role of being an audience member think our responsibilities and possibilities are, how we are construed by the performance and how we can exercise our own ethics within that. That one was ephemeral, unrecorded, existing in our memories, and ongoing. Consider this: performance is symbiotic. On one side, there are the creators, producers and institutions. On the other side is the audience. As an audience member, we too have an ethical agency, a power to act (or to decide not to act), to give attention, and to care for ourselves and others. But how easy is it to realise this power? When is a choice even made? How do we negotiate between responsibility to the work and to ourselves when we act as audience? In fact, do we even have an obligation to the work? Like everything, the answers to those questions are contextual and gradated, the process ongoing and the tipping point frequently subtle and crossed before we notice. As Brent Harris says, performance carries us along:

An event creates this situation where … there’s a context which carries me along and I might say yes to something - or might not say no to something in this charged situation, or if it pushes a little and a little bit more and a little more and everyone’s kind of in on this feeling … I walk away later and go 'oh that was actually quite dangerous' or I think 'I should have not participated in this'. There is that kind of charging or altering, but maybe that happens on the street. We’re always getting carried along or not getting carried along.

This describes life itself. We’re carried along making decisions in the moment, giving consent implicitly to all sorts of things. It is often only in retrospect that we look back and think maybe we should have said stop, disagreed, or actively changed the direction of something we were part of. The ways in which we are carried along, the ways we consent without consideration, and how we identify what conflicts with our values are part of what shapes us as people. As Mark Jackson in his interview commented:

The question of ethics is not so much what ethics belongs to me as a person but rather, what in ethics constitutes the possibility for me to say I am personal. It is the question of ethics that opens space for me to ask what I am, not what do I, as what I am, think of ethics. Ethics is that which construes what I am and in that sense there is something fundamental.

We bring with us, as audiences, our fundamental being, and certain performances challenge that. They ask us to consider the world differently, they push at our limits, and take us to, or beyond, the point where we make choices. That being said, we cannot overlook the coercive nature of performance, particularly when it takes place within recognised sites such as theatres and galleries. We struggle to get away from the formal etiquette. I still remember my sense of shame as a teenager as I clapped at the wrong point in a symphony and was hushed (I'm still a cautious clapper at classical concerts). Then there is the matter of leaving early. A common response to the concern of a work going too far is that you can always walk out. But how easy is walking out? I have only left four formally seated things: two films (The Gremlins when I was 8 and David Lynch’s Lost Highway when I was 20), a long drone work at Audio Foundation after 45 minutes, and a performance that ran late when I couldn’t face the prospect of having to walk 1.5 hours home because of public transport timetables. I consider myself an assertive person who is comfortable with going against convention, yet I've stayed in works in seated venues, where I have been bored, uncomfortable or in fundamental disagreement with the work. Obviously, the perception of whether you’re able to leave changes once you’re at an unseated performance. Milling around a space, at a bar or following something on the street lends itself to slipping away. But this doesn’t necessarily change part of the mindset which prevents us from departing or objecting to performative activity. But to say that we as audience are co-optable does not mean that it we are compliant or will respond in the manner that the creator desires. As dramaturge Murray Edmond told me:

The first responsibility to your audience is to understand its intelligence - and I think sometimes things go wrong because the intelligence of audience is misunderstood - often underestimated - I think, in terms of theatre anyway, the fatal thing about trying to confront audience is that you underestimate the intelligence of audience who will very quickly sidestep you and come back with something much better or ignore you or simply be embarrassed which is their right - and in a funny sort way the audience is never wrong if you decide you can get up there and do that and they don’t respond in way you want.

In recognising the symbiotic nature of performance, which asks us to consummate the performance by encountering it, we can also recognise how we, as an audience, create the performance, be it through an internal process of viewing, interpreting and recounting, or be it through a more external process of participating in its creation through contributing words and actions during the performance. Through this acknowledgment that we both read and write the performance, we can own our active role in the whole business. Hopefully this then enables us to expose ourselves to the work while protecting ourselves, chose if we want to contest the work, the structure of the event and the underlying norms it promotes, participate through choice not coercion, and do something amazing with the residue of the performance.*

So there we audiences are, coerced, deliberately passive, yet intelligent and participatory. Its a complex position and I think to negotiate it we need to recognise our own ethical construal, so that we can acknowledge when we are being carried along beyond what can be described as the creative challenging of societal constructs, and into the unethical. In short, recognise in advance what we are and where the ethical decision occurs.

You can listen to the Performance Ethics Working Group podcasts here or on iTunes.

The following people were interviewed for the podcasts: Christopher Braddock, Sally J Morgan, David Cross, Tru Paraha, Alexa Wilson, Stephen Bain, Craig Cooper, Sally Barnett, Rose Martin, Mark Jackson, Murray Edmond, Louise Tu’u, Becca Wood, Brent Harris, Val Smith, Sean Curham, Mark Harvey, Alys Longley, Carol Brown, Moana Nepia, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila, Hadleigh Averill, Alison East. You can read about them here.

Episode list

Episode 1: What is ethics? Launched at the Festival of Uncertainty, 23 March 2014 This first podcast introduces the idea of ethics as a daily practice and philosophical enquiry, exploring what participants think the broad concept of ethics covers.

Episode 2: How we treat our audiences In this episode we discuss what responsibilities performers and producers have towards their audiences and how these can conflict with the conceptual integrity of the work. We also talk about what can be considered offensive and who gets to decide this.

Episode 3: Reviewing performance art and ethics historically During the interviews a number of historical examples from performance art were reviewed. This episode explores the ethics and impact of these works.

Episode 4: The ethics of community engagement This episode explores the issues which research and residencies in and with communities brings up and how community arts projects and relational aesthetics projects can be approached.

Episode 5: Ethics of working with traditional and indigenous knowledges Recognising that the performing arts in Aotearoa New Zealand are structured and understood through dominantly western paradigms this podcast explores the complexities of decolonising performance.

Episode 6: How we manage the ethics of money In this episode we discuss fiscal ethics and how they can operate the performing arts. The culture of internships, alternative economies and decommodification of art are among the topics discussed.

Episode 7: Working relationships within the performance community This podcasts deals with questions of ethical relationships between performers and institutions, festivals, curators, directors and choreographers. It addresses a history of poor labour relations and and sometimes outright abuse in the field of dance as well as questions of collaboration and authorship, and the protection of the performer from real physical risks.

Episode 8: The University ethics process Many of the people who participated in the interviews hold positions at Universities across New Zealand. This podcast explore how these performers, directors and researchers negotiate a University ethics process initially developed for medical, sociological and anthropological research.

Episode 9: Authorship in collaboration This bonus episode focuses on how we handle authorship in collaborative processes. It brings together the participants thoughts on the topic from debunking the myth of solo authorship and recognising the positivity of influence, to adequate programme credits and audience or community participation.

Cover image credit: Alexa Wilson, ‘Star/Oracle’, 2014, Q Theatre. An audience member reads out texts from the audience about their opinions on the state of NZ in response to a question from him to the ‘Oracle’ (Alexa Wilson) about why he receives so many flyers everyday. Photograph by Jose G Cano.