Sleeping at Your Own Pā

For the first time, Tara McAllister returns to her tūrangawaewae to sleep on her marae.

Like many Māori, I have grown up away from my tūrangawaewae. I have grown up next to the ancestral mountains, moana and awa of iwi that are not my own. I have always been very proud to be Māori and am grateful that my koro is buried up in the urupā overlooking our awa so that I have a connection to that whenua. But in a colonised world, I have grown up detached from my marae. I can belt out the Tūhoe haka ‘Te Pūru’and the waiata tangi ‘Tāku Rākau’,but do I know haka or waiata about my own ancestors and whenua? Kāo. I have slept at many marae during my 28 years of life. But never, ever at my own. That is, until a couple of months ago.

Each year, I try to commit to a kaupapa on top of my work and whānau commitments that strengthens my connection to te ao Māori. Last year I focused on improving my te reo and did a diploma. This year, I was very excited to see information about an innovative course called Te Hapūtanga o te Ao Tikanga, run by Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. It was posted on our marae Facebook page, and I quickly enrolled. There are four noho throughout the year-long course and two Zooms every week. The best thing about it is the unique opportunity to learn about tikanga and the kawa of my own marae. An opportunity to connect.

I was a little nervous for our first noho marae, having only met my fellow classmates over Zoom. Like me, some were sleeping at our marae for the first time; for others, it was their first time ever coming home. Our whakaeke onto our marae began with the most beautiful pōwhiri. I have never witnessed a karanga so powerful before in my life. It was commanding, it was breathtaking, it was empowering, it was the absolute epitome of mana wāhine. There weren’t many dry eyes in the wharenui after that. It was an amazing way to start and break the ice.

I was so overcome with emotion I just stood and cried and mumbled a few words while my aunty held me tight

After the pōwhiri, we each stood up and explained how we connect to our whare tīpuna. Our kaiako said something along the lines of, “for those of us that have grown up away from our pā, at the end of this weekend I want this to feel like YOUR pā too.” I felt that in my bones and in my wairua. A spiritual call from my ancestors, Welcome home, you are safe, and you are loved. That intergenerational trauma, that mamae, that disconnection was so ready to be healed. Not only healed for me but healed for future generations, my tamariki and mokopuna.

I am an ok speaker of te reo Māori, so had I planned that when it was my turn to speak, I would stand up and mihi to our kaiako and the powerful kaikaranga. But instead of words, tears flowed. I was so overcome with emotion that I just stood and cried and mumbled a few words while my aunty stood beside me and held me tight. Those uncontrolled tears represented a lifetime of longing. They were tears of whakamā, tears of intergenerational trauma, tears for my ancestors and tears for my whānau.

In my work understanding racism in universities, we often talk about creating ‘safe spaces’ for Māori students and staff. I have never felt as safe as I did during this wānanga. I slept the best I have slept for over a year and was the most relaxed I had been in a long, long time. There is something so grounding and restorative about waking up in your own whare surrounded by intricate carvings of your tīpuna. Like a pēpi cradled in their parent’s chest, it felt safe and healing. I did not once feel out of place or uncomfortable; I felt at home. Well, I did permanently unbutton my jeans because of all the delicious boil up, fry bread and bread pudding, a massive rookie mistake.

I have never quite experienced aroha, whakawhanaungatanga, manaakitanga and kaitiakitanga the way I did during that weekend

Māori values like aroha, whakawhanaungatanga, manaakitanga and kaitiakitanga are plastered on the walls in many settings throughout Aotearoa, including our workplaces and schools. I have never quite experienced those values the way I did during the weekend at my pā. They were intricately interwoven into every interaction, in every harirū and every aspect of how we did things, how we related to one another. Every little thing embodied all those values and more.

I had the privilege of learning a waiata related to my own whenua and awa in my own whare tīpuna alongside my whanaunga. An opportunity that many Māori may never get. Despite being one of those Māori who is horrible at singing, I am really looking forward to the next time I need to sing a waiata tautoko. Because instead of singing a Māori anthem, one that everyone knows, I will be able to sing one that is relevant to me as a Te Aitanga a Māhaki and Ngāti Porou woman.

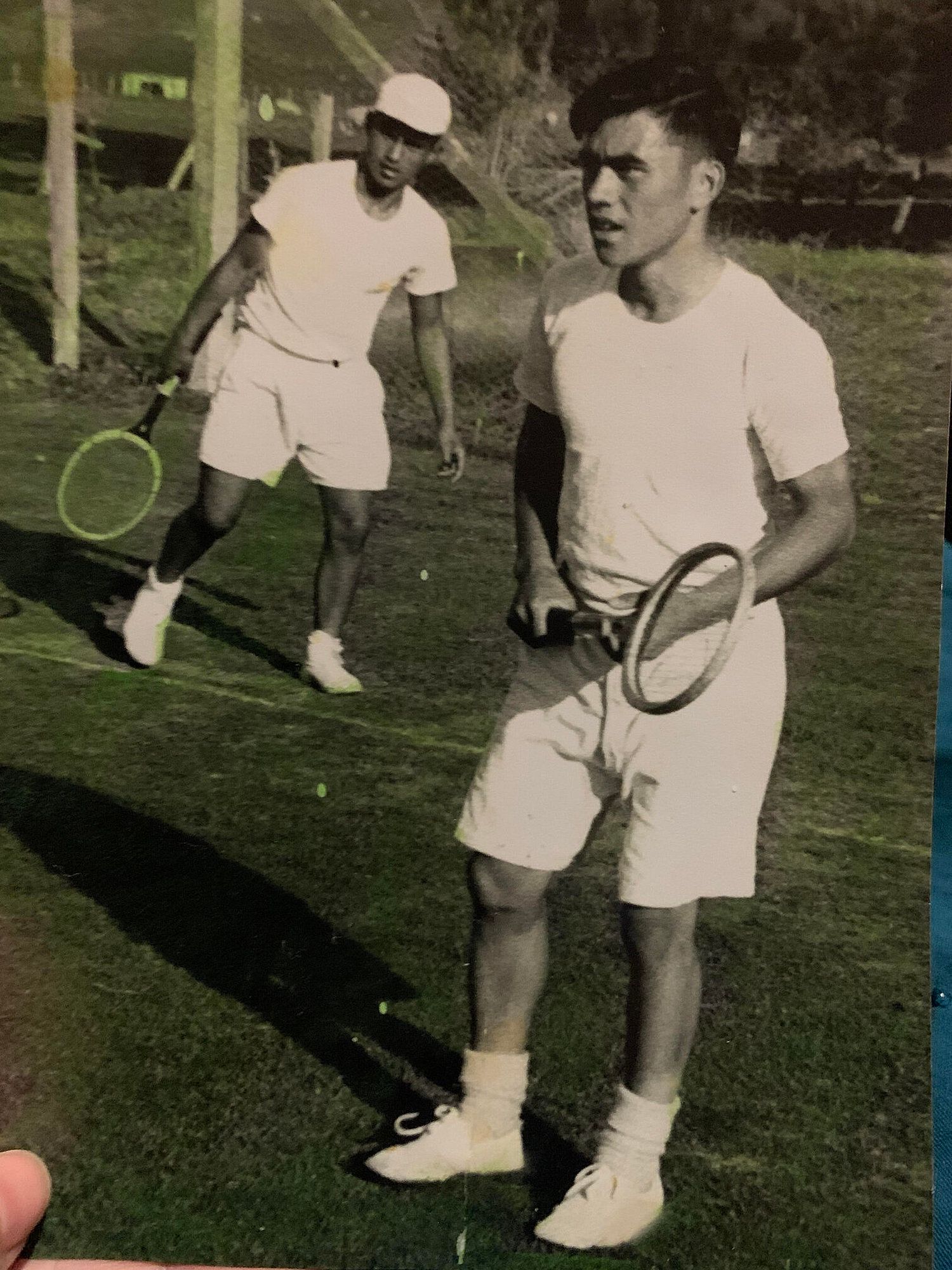

We had wānanga, laughed so hard our puku hurt, ate, cried and connected through shared whakapapa (importantly, finding the answer to the vital question – Are you my cousin?). We learned about the whakairo in our whare tīpuna. The kind of kōrero and mātauranga that I hadn’t had access to during other visits to my marae when no one was home. I was even given photos of my koro when he was younger, the only photos I have of him.

My koro

We had wānanga about karakia, which helped to decolonise my relationship with karakia. I am often asked, as the only Māori, to do karakia in rooms full of Pākehā. Up until our wānanga I had said no, because I refuse to be anyone’s token Māori. I am also an atheist, so I do not like karakia with a colonial influence. But my whakaaro and understanding of karakia were really expanded and changed. Now I think of karakia as the link between two realms: te ao wairua and te ao kikokiko, and that karakia are a type of rongoā that help guide and protect us. I have now been learning takutaku, which are traditional, pre-colonial karakia, and I incorporate them into my everyday life.

During our wānanga, we even got a special visit from Hineteariki – our ancestor and a taniwha. Not the type of taniwha Pākehā might think of, like some sort of scary monster or dragon-like creature. But instead, a beautiful taniwha, represented by one of the pou in our whare tīpuna, revealed itself in the mist. Our kaiako said that when people are at the pā, she always visits. It’s a tohu pai, a good sign. I attentively watched Hineteariki slowly rolling over our whenua, forming a heavy yet comforting blanket. She crept towards me deliberately and carefully, eventually knocking on the doors of the marae before disappearing as the sun rose.

Sleeping at your own pā, at your own marae, is a special type of rongoā. It made me wonder how different life was for our tīpuna who lived and breathed the pā before colonisation. Instead of Pak‘nSave and Countdown, they had the ngāhere, the moana and the awa. They were scientists, gardeners, tohunga, matakite, hunters and nurturers, in tune with the ebbs and flows of the environment and living in sync with the whenua.

You are no less Māori if you are not at your marae every weekend. You are no less Māori if you don’t know your marae

At the end of the wānanga, I reflected on colonisation, which stole my ancestral tongue and my whenua, and tried to steal my connection with my pā. It made me consider how we, as Māori, can often become lost and disconnected, separated from our wider whānau, hapū and iwi, and ultimately unsure of our identity. I wonder how different life would’ve been for Māori if our language wasn’t beaten out of our tīpuna. If our whakapapa wasn’t disrupted through the stealing of tamariki or the need to assimilate to survive. If we still maintained rangatiratanga over our whenua, if our way of life had not been disrupted.

Despite my contemplations on colonisation, I left my pā feeling mauri tau and with a new sense of belonging. The Pākehā saying of ‘having a full cup’ doesn’t quite encapsulate how I felt. I left with a full puku and kete, a replenished wairua. I left feeling grounded, connected and proud to be Māori. I feel good now that I know where all the dishes go, and I returned home ready to tackle another week of existing in a Pākehā man's world.

My trip home made me very grateful for ahikā, who keep our home fires lit and our pā tidy and warm. I give thanks to all those Māori who live by their pā and welcome us taurāhere home with open arms and hearts. For those Māori who haven’t made it home yet, kia kaha koutou. I think that there are lots of different ways to be Māori in te ao hurihuri. You are no less Māori if you are not at your marae every weekend. You are no less Māori if you don’t know your marae. Colonisation has taken, and continues to take, so much from us as Māori. You are not alone, because our tīpuna are always here to guide us through the ever-changing world around us.

Feature image: Ana McAllister