Sing Out, Dave! The Search For The New Zealand Musical

Musical theatre composer and writer Luke Di Somma surveys the history of musical theatre in New Zealand and asks, what road do we take to find the voice of the New Zealand musical?

Musical theatre composer and writer Luke Di Somma surveys the history of musical theatre in New Zealand and asks, what road do we take to find the voice of the New Zealand musical?

In 2011 Jason Robert Brown, the writer behind The Last Five Years and Parade and one of the great composers of modern musical theatre, was taking a masterclass for young actors in Christchurch. At the end of the class, one of the students asked an earnest question about how they could make it to Broadway. Brown answered that in a city like New York, you need something unique to make you stand out. “You could come and do New Zealand musicals,” he sarcastically joked, “Because there are heaps of those.”

Explaining that the Big Apple was already full of actors, he followed up with four words, delivered with lethal accuracy: “We don’t need you.”

While the room was reeling from those four brutal yet oddly apologetic words (I rather admired his honesty) it was the throwaway quip about New Zealand musicals that struck me. Not because I was offended, but because he was right. And it hurt. For the first time, I realised that my country had neither a national identity, nor an international reputation, in the art form that I loved.

There are New Zealand musicals. Our musical past is strewn with works inspired by overseas forms: musical comedies with songs, pantomimes and ill-fated musical blockbusters. In the search for our voice we’ve become comfortable borrowing tunes from other countries and singing them instead. We’ve made a lot of shows doing that, but few of them have kicked on to have successful lives.

The first wave of professional original musical theatre in this country was led by Roger Hall. Three of his shows – Footrot Flats, Love Off The Shelf (music by Philip Norman, lyrics by A.K. Grant) and You Can Always Hand Them Back (music and lyrics by Peter Skellern) – had long successful runs, even if they felt like ‘plays with songs’ rather than fully realised musicals. Other playwrights followed Hall’s lead, including Ken Duncum and Sarah Delahunty. Their plays with songs are musical-theatre-lite, gently working songs into their scripts without fully embracing the cohesion of the two that has come to define the musical. Hall also penned a number of pantomimes, often with composer Michael Nicholas Williams, and other New Zealand writers, including Gareth Farr and the late Paul Jenden, have also produced hit pantos. While these might be topical, entertaining and commercially successful, though, they’re more of a British form with a Kiwi marinade rather than a native musical theatre dish.

Elsewhere, the Mercury Theatre developed and championed several new musicals, including our first Māori musical, Mr King Hongi, about the Ngāpuhi rangatira and war leader Hongi Hika. Starring, George Henare, the musical was apparently a huge success but it's difficult to find much about the show; it’s never been revived and doesn't appear to be available for licensing. Peter Hawe’s Aunt Daisy! played several regional theatres in the late 1980s before embarking on a national tour and tanking, complete with exclamation mark.

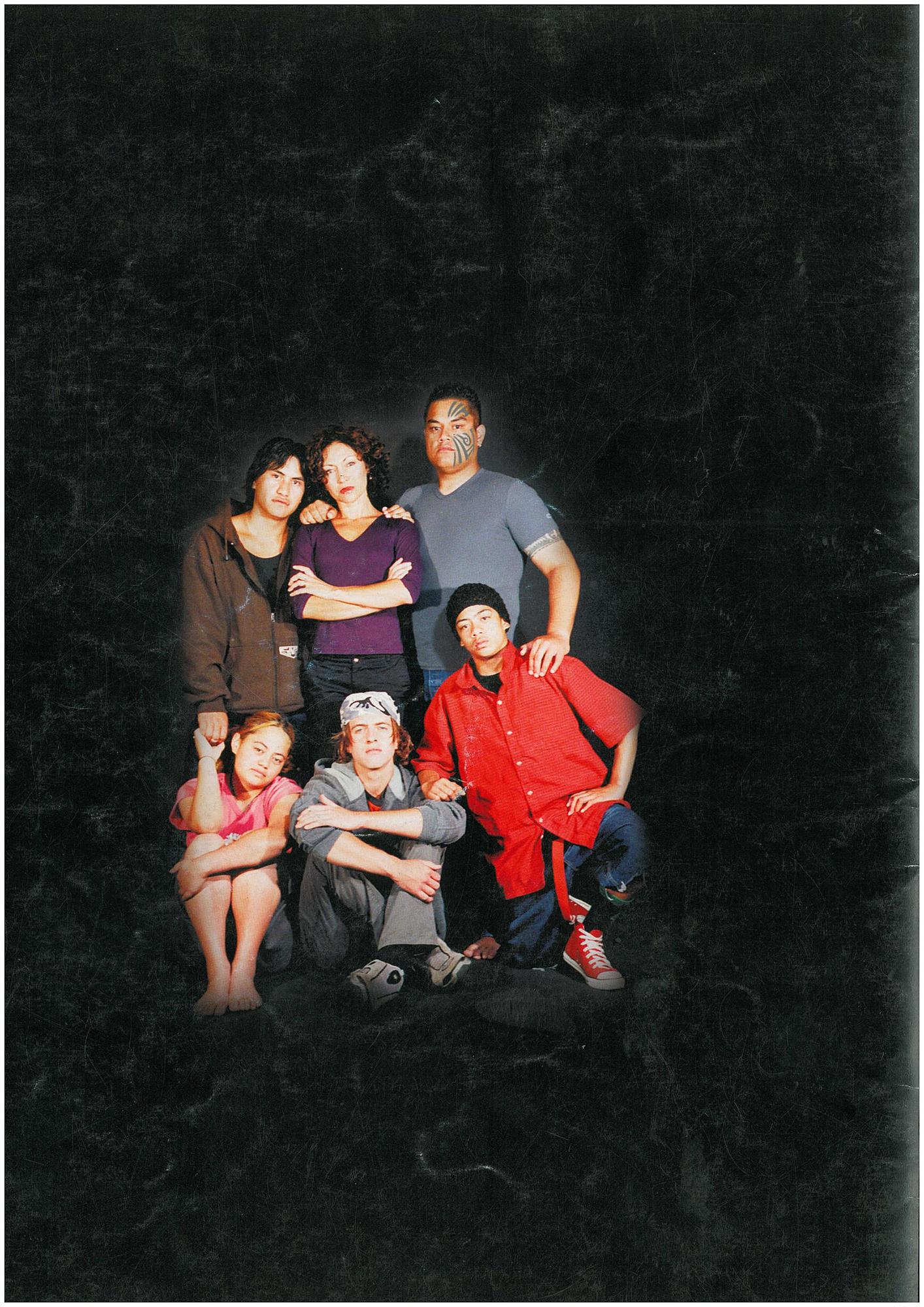

More recently, adaptations of two major Māori films led to a pair of blockbuster musical theatre flops in the early 2000s - Once Were Warriors: The Musical, and Whale Rider: The Musical. Not well received critically and commercial failures, they’ve never been seen or heard from since their premiere performances. A similar fate befell Braindead: The Musical, which opened at the Auckland Watershed and closed – early – at Wellington’s Downstage.

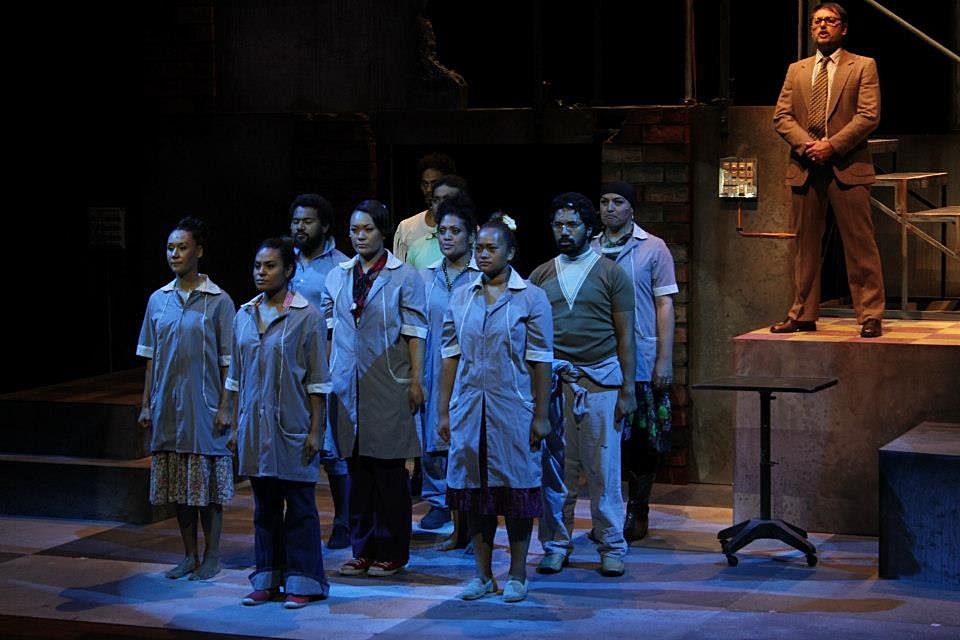

In contrast, Kila Kokonut Krew’s The Factory did enjoy commercial and critical success (mostly). Billed as ‘New Zealand’s first Pacific Musical’, The Factory opened in South Auckland before a high-profile transfer to the Auckland Arts Festival in 2013. It went on to tour Australia and play the Edinburgh Fringe but it struggled in Scotland, despite seeming like the ideal Kiwi musical on paper. It married a New Zealand Pasifika voice and story, heavy with themes of family, community and tradition, with the form of a traditional book musical. But in the journey to becoming a commercial product, in the journey to fit better into an artform that’s characteristically slow to embrace stories from other cultures, it lost some of its edge and authenticity.

Our musical past is strewn with works inspired by overseas forms: musical comedies with songs, pantomimes and ill-fated musical blockbusters. In the search for our voice we’ve become comfortable borrowing tunes from other countries and singing them instead.

This is far from an exhaustive list of every musical professionally produced in New Zealand, but theatre critic James Wenley’s verdict of our musical canon as “meagre” (made in a review of the musical I wrote with Gregory Cooper, That Bloody Woman) is undeniable. None of these shows have become part of our national repertoire, nor have they cohered into a catalogue with a strong and distinctive voice.

Why not? For a start, musical theatre is a young form and we’re a young country, one that only started developing its professional theatre industry in the 1950s. Musical theatre in America is rooted in vaudeville and musical comedy, and in Europe it comes from operetta and pantomime. We have no such traditions to build on. We don’t have the form in our bones.

Secondly, there’s our small population. Musicals are expansive and expensive. They need musicians, large casts, bigger creative teams and ever more elaborate production values; subsequently, they also need big audiences to pay for them. Our size means that New Zealand has a fairly bland musical theatre diet. Why would a New Zealand theatre company take a risk on a new show when they can trot out yet another production of Grease, knowing it will sell?

It also means, though, that we just don’t have the population or industry to support risks at that scale. All the classic shows we now bank on were new once – Les Misérables wasn’t a sure thing when first produced by Cameron Mackintosh and the Royal Shakespeare Company – but they also had resources behind them that New Zealand artists can only dream of. The producers of Whale Rider: The Musical explained in the New Zealand Herald that their show was “an adaptation of Ihimaera’s original book in a style akin to the stage version of The Lion King.” But Disney’s theatrical behemoth cost US$27.5m to produce. That’s nearly the entire yearly budget for Creative New Zealand.

Our accent’s also a problem. Musical theatre schools seem determined to bash the Kiwi out of us, but in order to find our own voice, we have to use our own voice. Whenever I’m coaching young singers and ask them to sing in their own accent, it’s a herculean task, such is the consistency of our American musical theatre diet. Our flat vowels, tendency to mumble and naturally unmusical speech patterns don’t lend themselves to mellifluous vocal lines. We’re happy to listen to the Flight of the Conchords sing in a Kiwi accent, but we’re not yet used to it on stage.

Beyond the practical concerns of budgets and accents, there are cultural reasons New Zealand musicals have struggled. For a character to sing on stage they must be out of words. The great director Jerome Robbins said that “when a character wants to scream they sing, and when they want to fight they dance.” (There’s another f-word which mirrors dancing as well. ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’ – yeah, right.) For a musical to work, we need characters and situations that require screaming and fighting. Naturalism works best on screen. Gritty domesticity is best explored in a play. Musicals require things to be a little larger than life.

Elevated material also allows for light, magic, possibility and hope. Musical theatre’s almost always about the end of the world, when singing and dancing is all we have left.

The traditional American musical (pre-Sondheim), for example, is a post World War 2 statement of American exceptionalism. The classic musicals made during this period are optimistic statements about love and nationhood (‘Oh What A Beautiful Morning’, “..they call me a cockeyed optimist”… “the sun will come out tomorrow.”) People in love, with strong beliefs, fighting for an even better world. These musicals sweep and soar; cowboys pas de bourrée and gamblers harmonise. The aspiration sings, preferably with strings.

Conversely, the British musical is almost always about characters – typically poor, cold and more often than not hungry – escaping an unbearably terrible situation. (“Please Sir, can I have some more...”, “Tell me it’s not true...”, “we are revolting children...”). Compare the two great ‘orphan’ musicals: while Oliver’s stuck in a nasty situation with thugs and criminals, his American sister Annie is almost unbearably peppy despite growing up in an orphanage. Annie belts out dreams of ‘Tomorrow’, whereas Oliver sings of having a “not a crust, not a crumb” and poignantly asks ‘Where Is Love?’ Annie might have a ‘’Hard Knock Life’, but she’s not about to be lured into a professional crime ring and befriend a woman who gets beaten to death at the height of Act 2. Where the American musical is about aspiration, the British musical is about desperation, and both these extremes sing.*

The producers of Whale Rider: The Musical explained in the New Zealand Herald that their show was “an adaptation of Ihimaera’s original book in a style akin to the stage version of The Lion King.” But Disney’s theatrical behemoth cost US$27.5m to produce. That’s nearly the entire yearly budget for Creative New Zealand.

Without the sunny optimism of the American Dream or the constant misery of the British class system, it’s not hard to see how the New Zealand musical might have an identity crisis. As a country, New Zealand is the very model of modern moderation – our manners, climate and politics are all moderate. We like success, but not too much. We like a warm evening, but not too hot. We like people to be kind, but please don’t get too intense. We’re fine. We’re sweet. She’ll be right. Yea, nah. Doesn’t really sing, aye bro?

Te Rakau and ARTCO knew this when they made Once Were Warriors: The Musical. Marketing the most expensive and high-profile New Zealand musical to date, they used the pre-emptively defensive tagline, “Every passion needs its own music.” Judging by Faith Oxenbridge’s review in The Listener, the defensiveness was warranted: “the singing and dancing softens the force and intensity of a story that that needs to be uncompromising in its telling.”

Oxenbridge wasn’t wrong. Te Rakau and ARTCO’s interpretation, hewing close to the traditionally anglo template of commercial musical theatre, used Māori performance forms like kapahaka and waiata but did so in a way that diluted the real impact they otherwise might have brought to the material. The same criticism was levelled at The Factory. In a review for Theatrescenes during the Auckland Arts Festival season, James Wenley identified a lack of bite: “by focusing so wholly on the conventional cookie-cutter love narrative, life at the edges is lost.” This desire to create a mainstream piece of work often means that edgier styles, forms or stories are watered down because of the audience's expectations of a musical.

Remember, most New Zealanders’ experience of professional musical theatre is rooted in the avalanche of blockbuster shows from the 1980s – Phantom of the Opera, Cats, Les Misérables etc. These were all unashamedly commercial entertainments, designed to bring in the masses. Our national consciousness of what musical theatre ‘should’ be is defined by this generation of shows, which explains why we turn to them when we try to replicate ‘what audiences want’, rather than leading with a more authentic approach.

In her review of Once Were Warriors, Oxenbridge also said that “the story struggles to fit the form.” But shouldn’t it work? Yes, there’s plenty of screaming and fighting, but it isn’t the right kind of screaming and fighting for the form as it was imported in the 1980s and 1990s. Musicals are often ‘tough’ but they’re seldom ‘hard.’ Both Once Were Warriors and Whale Rider were just too earth-bound for the traditional musical theatre treatment. Neither allowed for much levity or magic; there was little to no chance that light might come through to pierce their darkness.

In a musical, song functions as either an inner manifestation of our frustration or an external expression of what we really want. Such open, direct communication isn’t exactly typical of your regular Kiwi, especially your regular Kiwi bloke. Getting characters who don’t want to communicate to sing, then, can be difficult. Negotiating this transition from scene into song is the most important part of making a musical; it’s sometimes referred to as the point of “lift off.”

Rochelle Bright’s Daffodils - a ‘play with songs,’ which weaves classic Kiwi rock and pop numbers through its libretto – might be a trailblazer for the idea of a modern, distinctly Kiwi musical theatre. Based on true events that occurred in Hamilton, Daffodils tells the story of Eric and Rose, two teenagers who meet and fall in love in a field of daffodils, and their lives after. Towards the end of the show, Bright finds a sharp musical impulse, one both theatrical and grounded, in our lack of ability to communicate: Eric, struggling to communicate with Rose, sings the Dave Dobbyn hit ‘Language’ at her. But it's actually the soundtrack of his generation in his head as he stares blankly at Rose, unable to actually explain what’s going on, while she screams at him. It might well be the first musical theatre “lift off” that’s honest and distinctly our own. It’s a masterstroke.

Another show that sings in our own voice is He Reo Aroha. Created by Jamie McCaskill, Miria George and Kali Kopae, He Reo Aroha uses both traditional waiata and original music to tell an intimate love story. The show is about straddling divides: the actors speak and sing in Te Reo and English; the show is set in both New Zealand and America; the actors play instruments as they perform, weaving together music and theatre. Rather than having songs dotted through for variety like other intimate musical theatre pieces, song is intrinsic to He Reo Aroha’s storytelling.

A review of He Reo Aroha in the New Zealand Herald said, “[the show] does not shy away from soaring lyricism but manages to keep its feet firmly planted on the ground.” This might be the path forward. If American musicals are about the aspirations of dreamers and British musicals about the struggles of the downtrodden, “soaring with our feet on the ground” might be the mantra that unlocks an authentic New Zealand musical theatre voice.

Soaring might not seem like a particularly Kiwi verb. Many of our national clichés (“punching above our weight”, “tall poppy syndrome”, “Kiwi battler”) speak to a wider national truth: we’re not soaring, we’re ‘reaching’. Reaching to be recognised, to be relevant, even to be acknowledged. This impulse is a youthful, almost naive form of aspiration that’s distinctly our own, and it’s one we can already see in more recent musicals. In Daffodils, Rose is reaching for Eric, and Eric tries to reach back. In The Factory, Losa and Edward are not only reaching for each other, but for a better world for them and their community. Musicals are so often about the underdog, and that gives us an opening. We have a chance to fully embrace this and create our own aspirational musical theatre heroes.

Our love of ‘community’ can also sing. This in itself is a slightly amorphous concept; sitting somewhere between families and society, communities are bound together by a common purpose and torn apart by common threats. But big-heartedness sings. Whānau sings. The rituals, traditions and history in our various cultures sing. Our connection to the earth sings.

The Broadway actor Andréa Burns once told me that every song is a fight. And we love a good fight in New Zealand. We battled Everest, French eco-terrorists, nuclear power, apartheid and as is the case with my current project, we fought for universal suffrage. We are less apathetic than we give ourselves credit for. If we can embrace that distinctive brand of aspiration and soar with our feet on the ground, we may do more than just finding our voice; we may create a new voice in international musical theatre - a hopeful yet humble form where underdogs fight and communities sing. We should embrace our accent, find appropriate subject material, tell Māori and Pasifika and other New Zealand stories, and not be afraid to start small instead of trying to replicate expensive international models.

Musical theatre is the most popular and lucrative performing arts industry in the world, and our opportunity is huge. We’ve already caught up with our music, film and literature. It's time for musical theatre to do the same. It’s time to sing out.