Recontextualising the Silence: A Review of Pacific Underground Silent Spring Films

Complex feelings surface when watching 100 year old colonial footage, how are we supposed to react?

Complex feelings surface when watching 100 year old colonial footage, how are we supposed react?

On Friday night I saw the future and the past breathing in unison when Pacific Underground presented Silent Spring Films at Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision’s Siapo Cinema: An Annual Oceania Film Festival. Pacific Underground performed live music to the hour long screening of eight different silent excerpts shot in the Pacific between the 1900s and 1950s.

Nathaniel Lees introduced Pacific Underground, recounting how in 1992, he received a letter asking if he could direct a play, from a newly organised theatre company of Pacific youth in Christchurch. He agreed of course and Pacific Underground has since produced ten secondary school and eight main-bill shows. Creating beyond theatre, they tell Pacific stories through music, events and festivals; they’ve produced, two albums and ran the Christchurch Pacific Arts Festival for ten years. In 2016 Pacific Underground were the recipients of the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Vodafone Pacific Music Awards. In light of this award reflecting their decades of work, it’s worth noting their intergenerational make-up, with their two youngest members and performers at Silent Spring Films, still at High School.

With their distinct mix of talents, who better than Pacific Underground to approach what might be considered the challenging and sensitive topic of inherently colonial footage? Archival footage of indigenous peoples is problematic: it is of us, not by us or for us. Whoever is behind the lens is a significant determinant to understanding the reason for the film’s production, giving contextual understanding for the social and political landscape of the time. But more importantly who is in front of the lens?

Archival footage of indigenous peoples is problematic: it is of us, not by us or for us.

As a viewer, do I become complicit in the portrayal of dancing, labouring and performing ‘natives’? The screening consisted of both black and white, and colour film ranging from 16 to 20 frames per second. This rate makes actions appear slapstick and comical, is it okay to laugh? How do I wade through my own emotions of amazement at seeing hundred-year-old footage with a sadness of obvious racist structures? How do I reconcile the humour of canoe hurdling and a self-awareness that I don’t know nearly as much about the Pacific as I ought to? With the aid of PU’s soundscape, I was guided through these complex feelings.

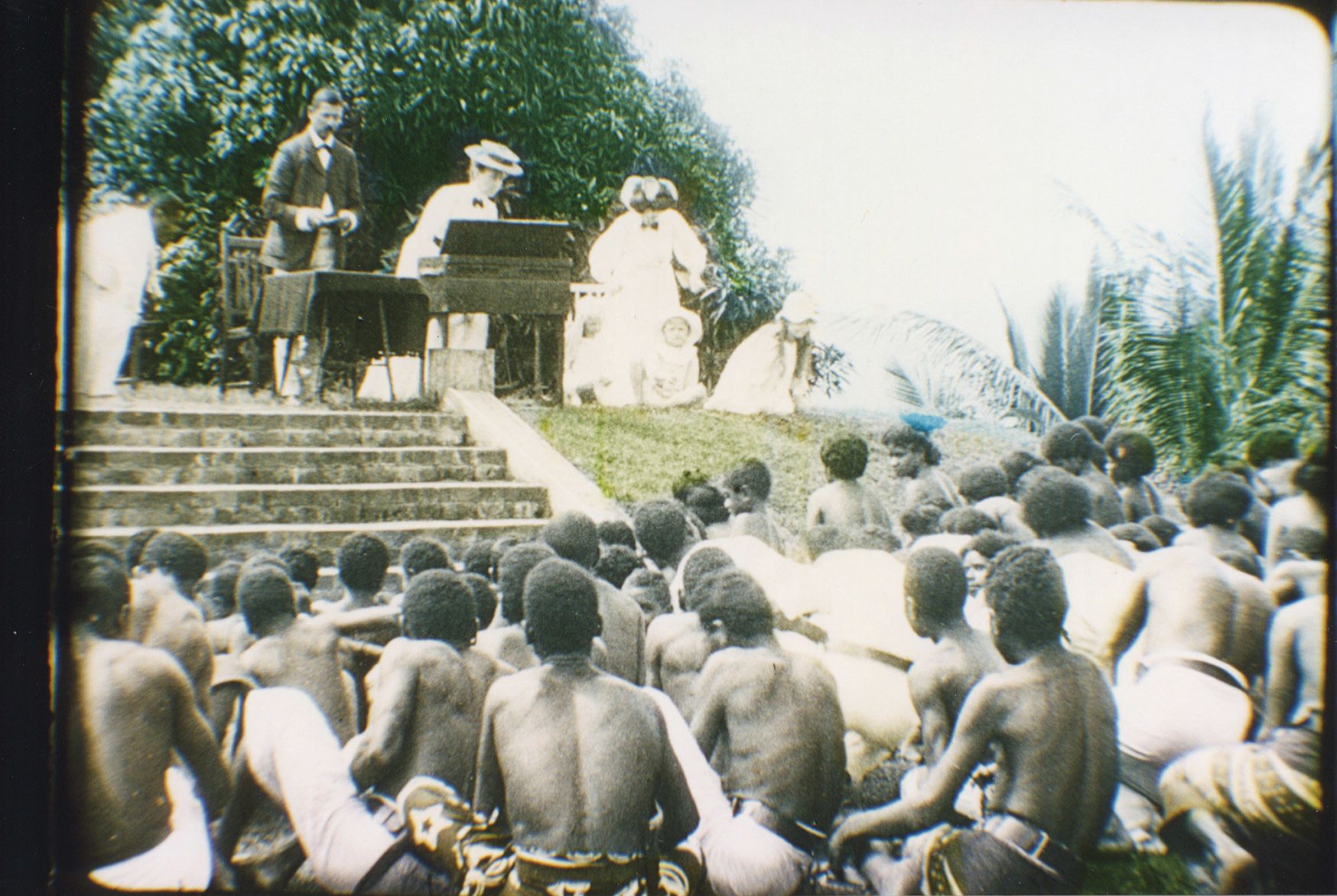

The first excerpt was from Fiji and the South Seas Island, compiled in 1907 from a newsreel and directed by JT Brown. This black and white compilation was actually shot in 1902, meaning it is 115 years old. It featured fire walkers from Beqa Island, Fiji, jumped to Rotorua and the Waimangu Geyser, then to hilarious waka racing and hurdling (where boats paddle up and over a log in the water). Pacific Underground played a range of acoustic guitars, a bass guitar, keyboard and pātē. Their sound was smooth and eased us into the silent film journey with them. The following footage titled Pacific Mission was from 1913 Vanuatu, or as it was known by some at the time, ‘New Hebrides’. It portrayed black and white film that had been hand-tinted, highlighting the blue skies and the bright orange borders of long skirts. A missionary family dressed in all white, appeared to be leading a congregation in devotion. Within the chronological screening of films, Pacific women in all the footage after this appeared clothed and covered.

At times when the footage appeared disconcerting, Pacific Underground’s music carried the audience through. They portrayed an ability to stitch sound and visuals together, forming a cohesive whole by adapting songs suited to each location. In the excerpt from Samoa, Coconuts and Copra, 1929, we saw that Samoa had the world’s largest coconut plantation and the scale of the copra industry of Apia. We saw people of the Solomon’s working in plantations, and written text portraying colonial theories about different Pacific peoples. Most importantly we heard the lyrics of a song Tanya Muagututi’a and Pos Mavaega wrote while at the 11th South Pacific Arts Festival in Solomon Islands, ‘Solomon is calling. Smiles say Hallo. Me belong you, you belong me’ reminding us that we are more than ethnic categories and our histories are complex.

Pacific Underground’s music guided the audience into cultural memories whilst keeping us grounded in today. Nostalgia is that bittersweet, fleeting feeling of simultaneously living and longing for a time that can only be reached momentarily. There is an inherent sense of loss associated with feelings of nostalgia, yearning for a time that exists only in memory, or the memories of those who, as they grow older, live more and more in the past. Pacific Underground acknowledged but did not dwell on loss. Their narrative interpretation and portrayal through music was a reclamation of Pacific ownership over ourselves, our images and our tīpuna in these films. Pacific Underground broached the colonial histories and contemporary realities of Pacific peoples while gently holding my hand throughout Silent Spring Films. They made it okay to watch.

There is an inherent sense of loss associated with feelings of nostalgia, yearning for a time that exists only in memory, or the memories of those who, as they grow older, live more and more in the past. Pacific Underground acknowledged but did not dwell on loss.

The New Zealand International Film Festival regularly features live music accompaniment to silent films such as when the Auckland Philharmonic orchestra performed Charlie Chaplin’s score for the 1921 film The Kid. There have been other films, the 1977 Italian horror Suspiria accompanied by an original score by prog-rock band Goblin, or the Carnivorous Plant Society who were commissioned to develop the soundtrack for the 1928 feature Lonesome. Perhaps more in line with Pacific Underground’s sensibilities, in 2012 the Toronto International Film Festival held the world premiere of Tanya Tagaq’s, an Inuit Throat Singer, live soundscape to Robert Flaherty’s 1922 silent and controversial film, Nanook of the North. In 2015 the Banff Arts Centre facilitated a residency called Re(Claim) which used live performance to recontexualise the silent films made of Indigenous peoples.

In 2018, Pacific Underground will be celebrating 25 years making them Aotearoa’s longest running Pacific contemporary performing arts organisation. As a member of a couple of still-young arts collectives, I am in awe of the amount of time they have been collectively making good work. The commitment to maintaining relationships, having clear communication, finding space for artistic development, not to mention funding restraints and real life struggles, can make collaborating hard. At the same time, collective making is logical. It’s the practical application of working from one’s centre, using a cultural compass to acknowledge and foster the potential that is abundant in our communities. The program for Silent Spring Films stated “This is a very special one-time collaboration”, I hope it’s not a one-time collaboration. More of this please, perhaps now more than ever.

Header image credit: Pacific Mission, (1913), Activities on a mission station in Vanuatu (in 1913, the "New Hebrides"). Courtesy of the Alan Roberts Collection. Frame enlargement. Stills collection: Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.