She Returns

Multi-disciplinary artist Pelenakeke Brown returns to Aotearoa from New York City and shares her musings with us as a disabled, Sāmoan/Pākehā immigrant who found herself, elsewhere.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

My ancestors and their marks live here. My mother’s grief lives here. All the things I cannot say live here. That voice whispers enter return enter she returns.

I cried during a Zoom call today. It was my closing presentation as an Eyebeam artist in residence, with most folks joining in from New York. I was speaking about my return to Aotearoa after being locked out of the USA when I was in London in early March 2020. And my quick pivot to assume the role as interim Artistic Director of Touch Compass, where incidentally I began my career as a wee eight-year-old dancer. I spoke about the abrupt transition into a leadership role as an Indigenous, disabled artist and the difficulty of holding all these identities, comfortably, especially after six and a half years away.

There is a lot of grief for me in this move. In NYC I was nurtured and in community with other disabled/crip, Queer and Trans BIPOC artists. My practice was perfectly aligned within a Covid-impacted world. I had been working for the past two years with technology and the way it holds disability and Sāmoan concepts, and as a disabled artist I have always worked from home, and rearranged my schedule based on my body and what I need. But when I found myself back – prematurely – I decided that in these times of urgent social change, having POC in leadership roles to impact and shift the arts culture is integral in supporting this change. And I didn't see anyone else doing this mahi, by us, for us.2

But it’s a colossal change in a very short time. Disability arts, especially in the performance/dance field, is growing and we are receiving more support in NYC. This year I also felt like I was on the precipice of something big with my practice and I had started to craft the working life I wished for.

After I spoke, academic Tina Campt, artist and fellow resident Elissa Blount Moorhead, and academic and artist Jeff Kasper affirmed my decision and spoke about the importance of having artists in leadership roles. To be held so warmly, in a Zoom room, with a community that I miss hard, made me cry. Awkwardly, I was still on the pinned video.

My work often explores the homeland, that call from the Moana, but I never thought she would be so swift, or recall me home like this.

My work often explores the homeland, that call from the Moana, but I never thought she would be so swift, or recall me home like this. When we cross the Moana a splitting occurs, we shape shift, our identities often become clearer, especially in a land where your people are not visible. I found the vastness of NYC freeing and took the opportunity to try new things, solidify what I believed in and quietly fuck up while no one was watching. Just like in Drag Race, every season, when a NYC queen walks in with a NYC attitude, and the other queens roll their eyes. It really is true, there is no better place or folks than those in NYC.

M o a n a she calls to me

I requested my medical records from the Manukau DHB in March 2018. I had always wanted to understand the circumstances around my birth, as my mum struggles to speak about it.The 103-page file was scanned and emailed to me in May. I read all 103 pages while sitting at my desk, in my room, in Washington Heights, while living in Trump’s America.

There was the expected medical jargon and boring notes but there was also a new, personal family history that I did not know was mine. I read letters of support a doctor wrote on my mum’s behalf to the immigrationcourt. “A mother should not be separated from her child.” These words felt eerily familiar with the constant news stories of children separated from their undocumented parents. This is the context in which excavātion: an archival process was formed. It grew from this excavating of my medical file and thinking about the relationships within this fragmented form. It also made apparent to me my mother's lack of agency, and the medical racism that she constantly encountered. I wanted to make work around this. I think my work will always be responding to my mum, somehow, the stories she does and doesn’t (cannot) share.

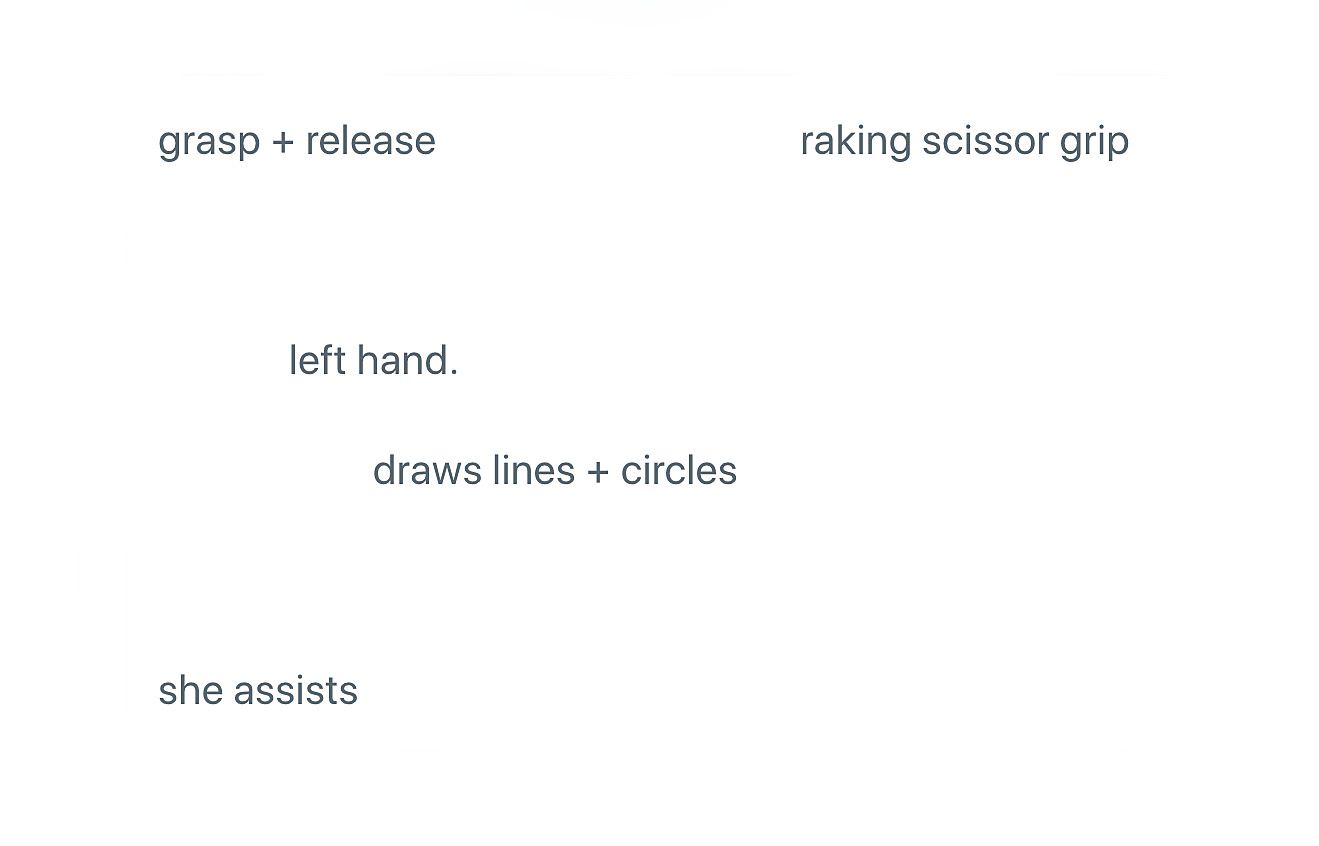

grasp + release raking scissor grip left hand. draws lines + circles she assists

That summer (June 2018) I was awarded a residency with Denniston Hill, a week to be mentored by acclaimed performance artist Xaviera Simmons, with three other artists, Sonia Louise Davis, Malcolm Peacock and Rina Espiritu. During this time the first iteration of excavātion emerged. I read my file over and over, made notes, recorded myself reading the file and tried to create movement scores. I also rested, floated in the pond, laughed and ate delicious food by artist, chef and farmer Ron Jean-Gillles. The theme of the residency was ‘respite’ and it was the first time an institution affirmed for me that resting is part of the work too.

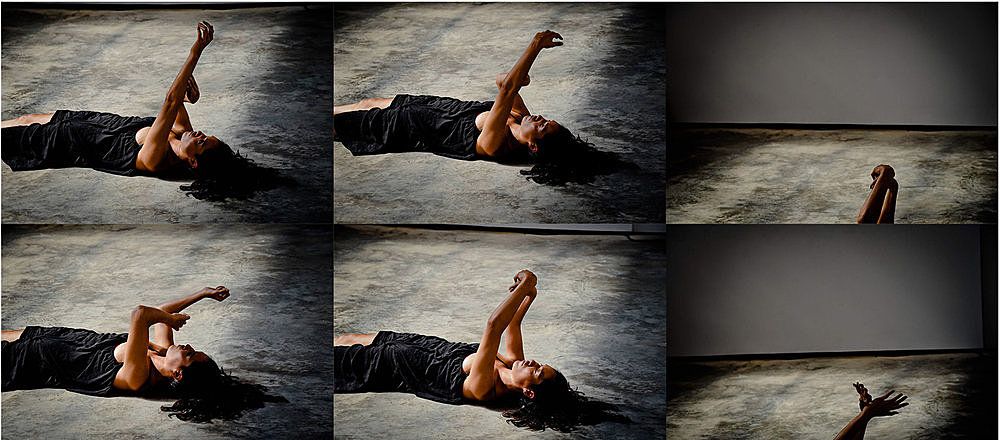

We each performed as part of Denniston Hill’s annual Open House. I created an installation of my medical file, an audio file and then danced from the floor only, using ‘respite’ as my movement score. I wasn't sure what I was going to do until right before. But the sun shone down in the barn, making a perfect rectangular spotlight while I slowly moved, from the floor, and danced with my hands, as they glittered in the sun and held the space. My earliest memories of the siva always focus on the hands, the gracefulness of their quiet intricacy flooded back. My most striking memory of Touch Compass as a child is watching Lusi Faiva dance the siva with only her hands, the rest of her body in darkness.

Stills from Excavātion, first developed in June 2018 at Denniston Hill. Photo supplied by artist.

The following year I received a Dance/NYC Disability. Dance. Artistry. Award as part of the Department of Cultural Affairs, Create Change NYC program. I received a grant, access to studio space with Spaceworks and support from Gibney Dance Center for a showing. I explored the excavation process further, dismantling the archive and re-imagining it. One of the ways in which I dismantled and re-imagined the archive was by taking my medical file and creating new, choreographic scores.One day in the studio I decided to try and make scores from the letters and notes in the medical file. I tried various methods but the prompt that really connected with the task was selecting words related to the body and movement. And very quickly I had a series of choreographic scores that made sense and that I could delve into. As my practice has emerged I have realised that I love finding dualities within works. Like the unexpected overlap between dance and medicine. And I like applying this to form, too: is it a poem, a drawing or a choreographic score? I would argue that it can be all those things.

is it a poem, a drawing or a choreographic score?

I also started to explore disability aesthetics within this work, especially in terms of audio description and the potentiality for poetics in this form. This also let me explore my voice because I realised up until that point it was missing, and the way my body was being viewed and spoken about was through these heavy, alienating, medical terms. The subject matter of my work is often very heavy and I like to think of myself as a pretty funny human. So, getting to think about the poetics of access, my voice and the way I describe myself I think opened up the work and is a direction I want to keep working in.

Sometimes I will check my weather app I will see that it is raining here in NYC and in Tāmaki. This duality always makes me think of my grandmothers. I have been seeing this duality everywhere lately.

That same summer I was commissioned to contribute work to the Movement Research Performance Journal. It was their first issue dedicated to Native/ Indigenous performance. For me this work was where my practice really shifted and the ripples from this work have taken me to the UK and Germany, and many more opportunities have found their way to me because of this work

I refused the initial prompt and, really, created my own. I was tired that day and I didn’t want to write about movement or dance. I wanted to refuse and really explore how you can move without moving. What does dance look like if it's not dance? I wanted to stretch the definition of dance. So I began with where I was and the tools I had in front of me. My computer keyboard. I thought about the framework that the keyboard offered me, I wondered what if shift, control, command, could be choreographic scores? I noticed the keys - + * < > : which reminded me of the markings found in our tatau. I loved that there was this ancestral knowledge in this contemporary tapping tool. And on my computer keyboard enter/return were the same key. That felt Indigenous to me, when we enter we return, time for us is not chronological. We enter the future facing the past.

I noticed the keys - + * < > : which reminded me of the markings found in our tatau.

My second work Crossings as part of the Mana Moana, Mana Wāhine exhibition with the in*ter*is*land collective last year explored this mahi further. Beginning with transformations that have occurred in my family and by exploring what it means to cross the moana, and our stories of immigration. What knowledge do we lose, change or are gifted in these exchanges? Thinking about transformations and storytelling like the story of Taema and Tilafaiga whose journey led to a splitting but also the gift of new knowledge with tatau.

Crossings. Computer generated image, 2019. Displayed at the Mana Moana, Mana Wāhine exhibition in London, curated by In*ter*is*nd collective.

Technology allows me to time travel, commune and communicate from the comfort of my bed. It holds crip time for me. Alison Kafer defines crip time as "rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds." Crip time always reminds me of the vā.

University is where I encountered the vā, through Albert Wendt’s seminal text ‘Tatauing the Postcolonial Body’. Something that I deeply knew but hadn't had the language for. I went searching for my culture at university but I realised I already knew it, had experienced it and I was less ‘afakasi’ then I thought. But I still never saw the disabled Sāmoan body in any of the art I was studying. Connecting the vā with my crip time is important to me because I always struggled, growing up, to reconcile my two identities: disabled and Sāmoan. Disabled spaces are often very white and Sāmoan spaces can be very ableist and not sure what to do with the disabled body. I often think that the disabled body often breaks the vā or is confronting for the vā. So to connect these two concepts together is fundamental, because I want to see more Indigenous, disabled folks be affirmed in all their communities.

Disabled spaces are often very white and Sāmoan spaces can be very ableist

The vā for me is also the framework that I will continually return to. It’s always where I begin my practice. What are the relationships that are occurring in this time and space? These relationships can be between myself, or can be larger, such as what are the relationships occurring within the archive, who creates the archive and relationships between BIPOC and the medical industry.

There is so much more to say about my journey to where I am today, but language and relationships are what I continually return to. Articulating the disabled, crip, Indigenous body is a space that is not often explored. Extending our definitions of movement and using language to support this through self-articulation, poetry and finding multiplicities in spaces is where I hope the disability arts community will continue to grow.

return and enter are one and the same when I think I am returning I am in fact moving forward

1 Edited excerpt from ‘A Traveling Practice’,by the author, published in 2020 in Movement Research Performance Journal issue 52/53, Sovereign Movements: Native Dance and Performance.

2 This references the disability rights movement phrase and tenet “nothing about us, without us”. It was heavily used in the 90s and asks that no policy about disabled people be decided without disabled people involved: disabled folks know what is best for them.

CNZ Logo

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.