Self-Addressed Letters to a Young Poet: The ‘Unsupported’ Artist

Stuart Wall explores what exactly it means to be an 'unsupported artist' - earnest, but unrecognised - in light of the prevailing conditions of our time.

The artist’s practice is strengthened by adversity. Is more adversity better? John Berryman says ‘the artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business’. Could we say then that the artist’s practice is strengthened by the protraction of her primal struggle against the perdition of anonymity, against poverty and (esp. interest-accruing) student loans, for the good will of others and security from insult and offense and undervaluation? Yes—to a point. Of course we rarely choose adversity. When art is life, a lack of recognition can feel like a kind of existential injustice.

An Important Distinction

Joan Fleming: … I am interested in your opinion about the myth of the tortured artist, and its usefulness for a society badly in need of healthy models of creativity. Most of the writers I know are struggling to make important art, but they are also struggling, equally hard, to live healthy, connected, value-creating daily lives. Do you think we are moving past praising the glamour of the non-functioning creative genius?

Eleanor Catton: I hope that we are. I find the idea of unsupported genius deeply distasteful: it disrespects mothers, and fathers, and teachers, and lovers, and all the accidents and opportunities and coincidences that conspire, along the way, to help create and launch an artistic sensibility. We need a new model: one that doesn’t depend on outmoded gender norms, destructive values, and the profoundly ugly idea that to be indebted is to be demeaned. Kindness is a core value for any artist, but most especially for a fiction writer: a self-centred person can’t see the world from another person’s point of view.

*

Catton is right in every part of her answer, though the answer might belong to a somewhat different question from the one posed. Fleming asks about the ‘myth’ of the ‘tortured’ or ‘non-functioning creative genius’, while Catton answers in terms of ‘unsupported genius’. If she means to imply that the tortured artist is tortured essentially because she’s unsupported, the suggestion is problematic. But I don’t believe she considers the terms interchangeable. I’m pointing this out not to find fault with Catton for answering a different (and to my mind more vital) question, but to emphasise the terms and call attention to the very important distinction she makes.

Catton implicitly distinguishes, as we so often fail to do, between (1) the formal support of the boards of judges and bodies of consensus that establish an artist’s public credibility and (some degree of) financial freedom and (2) the personal support of the people at the heart of that artist’s life. The latter, categorically more important than the former in the artist’s development, goes unrecognised and is dishonoured in the reductive idea of the ‘unsupported genius’. Three dichotomies emerge: between formally supported and unsupported artists; considerate and abusive artists; and those who recognise their forebears and benefactors and those who do not. Many artists come to mind that are a combination of the first part of each dichotomy. Then there are those that combine the very opposite traits. We tend to hear from both these ends of the spectrum.

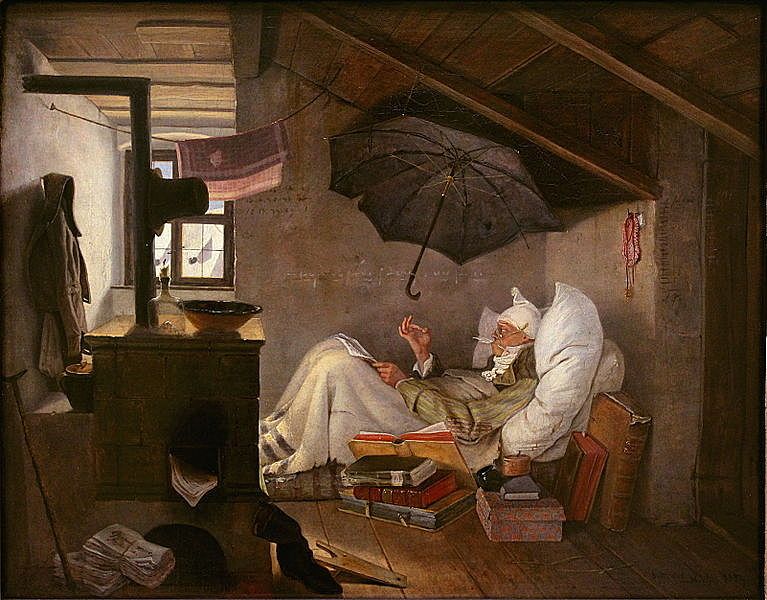

We hear less from the artists in-between. I mean the ‘formally unsupported’ artists who nonetheless do acknowledge their forebears and benefactors; who do not render themselves dismissible by resorting to abuse and backwardness in going unrecognised. In short, I think there is such a thing as ‘unsupported genius’ that is not distasteful and remains problematic. I’d choose a word other than the knotty ‘genius’, which seems to caricaturise the passionate artist, suggesting a kind of 19th-century, non-relativistic, Nietzschean belief in her superiority. I think we can simply say ‘artist’ and mean, if we want to distinguish between careless, uninspired, superficial artists and industrious, talented, rigorous ones, the latter. The otherwise ‘tortured’ artist belongs to another discussion.

Consummation and ‘the Other’

What is the deep compulsion I feel in a heavy Kapiti sunset, or down the marathon coastline of Muriwai, to share it with someone else? How is it that seeing this thing alone leaves the experience somehow incomplete? If I take it to the grave of tomorrow it’s lost forever. How much more so my art—since I created it, since I am the sunset—and thus my need for others to experience and thereby consummate it? For the artist whose art is essentially identical to her salvation, the eyes (or ears, etc.) of other people, ‘the Other’, are the very consummation of her work, as sharing a sunset is the consummation of experience.

Difficult questions arise from this formulation of ‘consummation’: how many ‘Others’ will suffice to ‘consummate’ (for example) a poet’s work? Will a few close friends, mentors and writers she respects do? Or does she need widespread approval? Why, especially if a poet is ambivalent about the opinions of the wider poetry community, let alone those of a general public that doesn’t even read the stuff, should she seek approval from these quarters, and how could such ‘Others’ possibly ‘consummate’ her work? Or is it the case that sheer formal recognition, the wider the better—without considering who constitutes her audience—is the necessary thing, as non-qualitative as a blind vote? Of course the answers must be totally subjective. But we’ve heard and believe that the great ‘consummation’—‘making it’, as in, ‘I’m going to make it as a poet’—is an illusion, or at least that it won’t make us happy. This doesn’t make it burn any less.

At the heart of this formulation is the Western drive for ‘immortality’, the figurative kind Shakespeare achieved: ‘literary immortality’, a drive at least as old as Gilgamesh. This drive ranges in volume among artists, among people; what a blessing if it’s soft as distant birdcall in you! Kurt Vonnegut explores this idea from underneath. One of his most compelling characters is the terribly underrated sci-fi writer Kilgore Trout, who writes masterpieces and then throws them away:

So he kept his war-surplus Navy overcoat on when he told the clerk at the shelter that his name was Vincent van Gogh, and that he had no living relatives. Then he went outdoors again, and it was cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey out there, and he put the manuscript into the lidless wire trash receptacle, which was chained and padlocked to a fire hydrant in front of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

– Timequake (1997)

Isn’t there something truly perverse about this act? About someone who devotes his life to art and bins his work, indifferent to the Other, to consummation? How jaded or sublimely detached does someone have to be to turn out like this? What is Vonnegut saying about Kilgore Trout and the world?

‘The Perfect Articulation’

At times I’m plagued by insecurity. Round and round my head spins the cartoonish rotary of insults and background-defining phrases like ‘cultural capital bankruptcy’ and ‘lower middle class’ and ‘lost years’. It often comes out in my poems; the following one appeared in Sport 42. The title is taken from Matthew Arnold’s 1869 collection of essays Culture and Anarchy.

Culture & Anarchy in Late Democracy

Adam among the jackals and jackdaws

read his father’s books winning fantastic

knowledge: the heights of angels, where

hail is kept, names for everything—a raspberry is

composed of drupels. Even as he read the names

pounced, battered, chest and jaw. That’s how

he knew them worth knowing.

Kept them in the east under a dragon tree.

Children from other clans approached, curious.

They were well within reach, always within reach

but somehow unreachable.

Too often I fall into a reverie under the powerful illusion that articulating the injustices I’ve felt could reverse them.I’ve seen this dream of perfect articulation play out at open mic nights: people desperate to exorcise their pain by way of its illustration and to consummate their poems through the ears of the audience. They want to be recognised. We want to be recognised.

How many of us in our low jobs have struggled to overcome the disdain of those we serve? How often have we been reduced to sad exercises of precision to exact respect? I wish I didn’t care what people think, but twelve or thirteen years—far fewer than many!—of getting shat on serving people in arenas of displaced aggression without the cultural capital-infused sense of the world as my oyster necessary to soar above insult, soothing myself with inapt quotations (‘What’s madness but nobility of soul/At odds with circumstance?’), charging the bullfighter’s red cape of the ‘perfect articulation’… Where is the justice?

The Sore Loser: A Dialogue of Foppish Pigeons

Two one-footed pigeons coo and squabble under a table outside of Pegasus Books in Left Bank off Cuba St. Wellington.

I deserve that prize more than the nightingale. My work has more merit.

According to whom?

According to me, and clever birds with taste.

Tell me what constitutes your ‘merit’.

In short: rigour, my unique voice, the high stakes of my songs, their intertextuality, perspicacity, the manifest suffering behind my work that is its strength and gravity…

And the nightingale doesn’t demonstrate these things?

No, or at least not as much as I do.

Aren’t you assuming a somewhat outmoded, hierarchical rubric and anyway, who says even if your work has all these fine qualities that it’s actually good? That it’s relevant? That it’s enjoyable or valuable or whatever to hear? Can’t you think of screeds of sparrows who are, notwithstanding their gravity and compassion and eminent proficiency, mediocre?

Yes, of course. But the judges, the judges are unqualified, and conflicts of interest abound!

How can you really assess the qualifications of these judges? How can you isolate them and their decisions in the scheme of the singing world and more generally of avian nature? I’m reminded of something Tolstoy says in the second epigraph to War and Peace, in which he asks who is responsible for the movement of masses across Europe in the Napoleonic Wars. His conclusion, contra the so-called ‘Great Man Theory of History’ is a structuralist one in which ‘the movement of nations is caused not by power, nor by intellectual activity, nor even by a combination of the two as historians have supposed, but by the activity of all the people who participate in the events, and who always combine in such a way that those taking the largest direct share in the event take on themselves the least responsibility and vice versa’. We might say by analogy that movements and opinions in the arts are equally complicated and diffuse, and that it is unjust to hold responsible individual birds or boards for what we perceive as failures of insight based, again, on hierarchies that may be largely outmoded.

Oh will you quit playing the owl’s advocate! Surely you’ve come across incompetent judges and conformant cormorants that get ahead by networking and posing and consciously or not winning over flocks with specious, soulless work? And once they’re on the gravy train of awards and distinctions, and judges and audiences are used to associating their names with excellence, they become locked in to the exclusion of more interesting, authentic tui?

So now you’re blaming the birds themselves? If it’s not the judges’ fault it’s certainly not the birds’ in reflecting certain reinforced artistic values of the day! And what songbird consciouslysets out to deceive? Anyway, it’s only natural for excellence to continue to be rewarded if no worthy competitors are to be found. There are only so many perches available.

If we could believe in a rigorous meritocracy…

You really are a sore loser…to return for a moment to just desserts, do you really deserve this reward more than the nightingale? Haven’t you had a good nest, a good education, a privileged life that has allowed you to make better decisions and achieve greater freedom from the manufactured desires and addictions birds are fed that compromise their ability to find equilibrium, if not happiness? In what sense are you, who have been groomed for success in the world, more deserving than another who has expended as much if not more energy on her singing, suffered as many and very likely many more insults and defeats in her life not because of any inherent fault but merely due to circumstances—in what sense do you deserve recognition and worms more than your less privileged competitor? Anyway, do you really want widespread approval? I’m sure I’ve heard you parrot the classical choristers who maintain a ‘contempt for glory’, who consider travel ‘a fool’s paradise’ and all that.

But that’s the nature of competition. You sound like Shelley: ‘How many a rustic Milton has passed by,/Stifling the speechless longings of his heart,/In unremitting drudgery and care!’ What would happen to art if we had to account for everyone’s nest and then adjust in the spirit of equality?

Broad Strokes

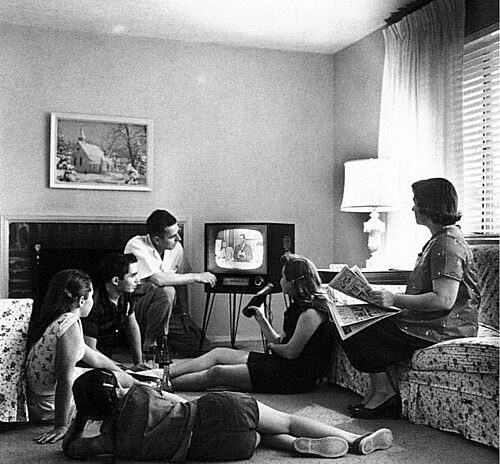

Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned

– Marshall McLuhan (1964).

There’s an Irish folktale called The Field of Boliauns that seems like a good allegory for we poets. Tom Fitzpatrick compels a leprechaun to take him to where a pot of gold is buried under a boliaun (ragwort) plant. He ties one of his red garters to the tree and makes the leprechaun promise he won’t remove it when he, Tom, goes off to get a spade. When he finally returns, ‘lo and behold! not a boliaun in the field but had a red garter, the very model of his own, tied about it; and as to digging up the whole field, that was all nonsense, for there were more than forty good Irish acres in it’.

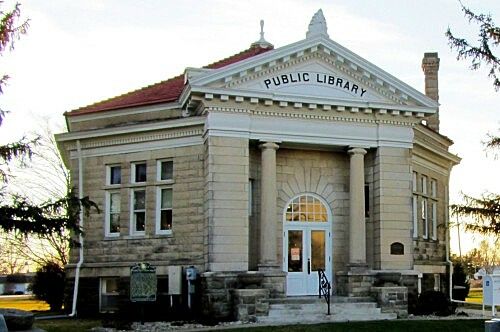

With the saturation of our subculture of poetry—the proliferation of journals, books, etc.—how can I know where the gold of artistic brilliance lay buried? Who will hear those poets knocking, buried alive in their virtual, existential boxes? Those nearby, presumably.

With the speed at which artists appear and disappear from public consciousness, how long can anyone pay attention? It seems for now and at least the near future we can reach audiences wide in space or (perhaps) time, but not both. Who can tell? Only Time.

Something like this has been part of the postmodern experience for decades, but the Internet, which accounts for the critical mass point we’ve passed, has predominated only in the last 15-20 years. The time-honoured reply is that no important change has occurred; we’re just moving farther along a trajectory: isn’t it impossible for Carson to achieve the fame of Stevens, as it was for Stevens of Whitman, Whitman of Shelley? Yes. But like the steam engine’s effect on the course of human social development, the Internet has radically steepened the trajectory, making for a paradigm shift. A next-level expression of democratisation. A paradigm of canonisation—as opposed to ‘the canon’ as such—is rapidly becoming outmoded. We’re experiencing a great, humane movement of democratisation in terms of ever-wider access to ‘consummation’, however diffuse. And of course the Internet itself is an artistic medium, one with its own canon: Tim Berners-Lee, Edward Snowden, Bjarne Stroustrup. Nick Montfort and Stephanie Strickland’s digital work 'The Sea and Spar Between' with commentary and ‘Writing’ by Tully Hansen are exciting examples of the on-going confluence of poetry and technology.

Should we fear the shift of this paradigm of canonisation? Can we imagine a time when Shakespeare will subsist in a pinch of semantic dust of dead metaphors, lost to humanity? This is difficult. But its reality doesn’t constitute ‘an international state of emergency’ in the words of Celeste Oram, whose sketch of the future of music after the ‘Beethovocalypse’ in her recent article I love.

Our time calls on us to think about our drives and existence as artists in different ways. Can we come to terms with our inheritance, a drive for immortality that has behind it the (discontinuous) momentum of thousands of years, the one turning us like sunflowers toward the immortality of Shelley, Whitman, Stevens, Carson...? The emerging model requires us to adjust ourselves as best we can to a different type and scale of artistic consummation, to low-ceilinged rooms in the virtual world, old halls and skies in the local one.

We can sleepwalk in the footsteps of our forebears in the drive for glory if we ignore the conditions of our time. But can we free ourselves from this thing, inextricable from so many aspects of Western culture? One might call these conditions an idealist’s dream, though one few idealists would choose.

In the Symposium Plato describes the drive for immortality in relation to poiesis, ‘making’ or ‘creating’. In her creation the maker (e.g. the poet) extends herself beyond her lifetime: ‘such a movement can occur in three kinds of poiesis: (1) Natural poiesis through sexual procreation, (2) poiesis in the city through the attainment of heroic fame, and, finally, (3) poiesis in the soul through the cultivation of virtue and knowledge’. What other kinds of poiesis are there? What renaissances of physical space will collect us, thriving under the giant shadow of a tiny, globalised globe? Can we return to the caves hollowed of the supernatural and paint for painting’s sake?