SEELA

Chef romesh dissanayake's grandmother Seela was an amazing cook, but also cheeky, rebellious and full of life. It's why the Sri Lankan pop-up dinner series is named after her.

How old were you when you first realised you weren’t white?

I was 16. 2004. It was the first time I’d ever had a girlfriend. Jessica. She invited me over for dinner to her house in Wadestown. There I sat amongst the buttered peas, the mashed potatoes and the gravy, looking down her mum’s low-cut top as she served me a spoonful of Moroccan lamb tagine. Her arms so slender and elegant. Golden bracelets and rings wrapped around a vintage silver serving spoon. The lamb so succulent and tender. The house, so warm… so carpeted.

There is a picture of Jess’s parents on the bookshelf in the hallway. Her mum is dressed up as a stewardess; the dad has aviators on and a tall cocktail glass with a little umbrella in his hand. Tropical/Top Gun vibes. I stop and stare at the picture on my way back from the bathroom. I don’t think I’ve ever seen my parents hold hands. Or hug. Or touch alcohol. You know what I mean when I say that an inside joke, a slight smirk, a before-your-time reference in a small group can just ankle-tap you from behind, and, with your face in the dirt, you realise: HOLY SHIT< I’M NEVER GONNA BE WHITE :’(

The lamb so succulent and tender. The house, so warm… so carpeted

This realisation hits hard, especially when you’ve spent so long trying to make yourself really smol and cute and have been pulling it off really well of late. It’s like turning up for the first day of school and realising you’ve worn your gym gear instead of your summer uniform, or like shitting yourself at assembly and trying to blame someone else for throwing shit at you as it oozes down your sock. It’s that squelch inside your shoe as you walk out past everyone.

That which makes you different sometimes presents itself in the ugliest ways, at the most inconvenient times. But these things are not new. No immigrant story is without struggle, without its fateful missteps. I was teased in Sri Lanka for looking Japanese, teased in Aotearoa for having an unpronounceable name. The Goldilocks zone for a person of mixed race is truncated by circumstance. You gaslight yourself. Questioning: Where do I belong? Who do I belong to?

As I stare at the photograph on the bookshelf of Jess’s parents in their air-crew uniforms, it is as if they are winking and laughing at me. At my expense. I become miniature in the space I occupy. Though there’s no reason for it, I keep their jokes and their generosity at arm’s length. And in this moment, I am alone.

**

By 2016 I had been cooking for eight years. A job. An occupation. A habit. It got me out of Tāmaki Makaurau and through Sydney, where I worked within the safety and security of big restaurant groups; to a luxury resort island in the Whitsundays owned by a multi-millionaire; to the iron-ore mines in the Pilbara region. In that small settlement in the desert, flies would fly into your mouth mid-sentence and rust-coloured dust seeped into your ears like sand through an hourglass, filling your dreams at night with a hellish amber glow.

Cooking took me through Japan, through Laos, through Cambodia, through the Kandyan hills, through Michelin-starred restaurants in Barcelona, chasing the ghost of Ferran and El Bulli like everyone else in the late 2000s. Relentlessly, I pursued a career that was often unforgiving and ungratifying with devotion and determination I can only describe as Olympic.

Anyone who’s worked in an ostentatiously mid-to-high-end restaurant with a slick fit-out and plush comfy chairs... knows it’s a farce on some level

I worked 70-hour weeks, woke up at 2am to do the breakfast shift, staged (an unpaid internship) at other restaurants on my days off. My body was hunched and thin. My butt disappeared. My knees constantly ached. I missed countless catch-ups, birthdays and weddings. Once-healthy relationships were starved of sustenance and withered on the kitchen counter like supermarket basil.

When a friend sent me an article last week on Ed Verner and the toxic, manipulative and abusive work culture at Pasture – one of the top restaurants in the country – I sighed because it brought back all those memories of feeling exhausted and depleted. Anyone who’s worked in an ostentatiously mid-to-high-end restaurant with a slick fit-out and plush comfy chairs, one that glorifies ‘whole animals’ and ‘cooking with flames’, then you know what it’s like. It’s a farce on some level. It’s a show. It’s pressure induced by pretense, and under pressure tempers flare, people do dumb shit, others go to war. It’s time we stopped using an outdated brigade system as the basis of how a kitchen team is assembled. Break down hierarchies. Decentralise. Don’t be a dick.

Note: A young chef will cherish a knife collection like a childhood blankie

In January 2016, while crossing the Strait of Gibraltar to get to Tangier, I lost my knife roll. Note: A young chef will cherish a knife collection like a childhood blankie. It will bring them great comfort and security, but (like a blankie) it’s weirdly possessive and immature. I remember the moment. I felt like Che Guevara (problematic state-sanctioned executions aside) when he dropped his medical kit and picked up a gun, symbolising his transition from doctor to guerrilla fighter. As I crammed my chef whites and checked pants into the rubbish bin at the port, I didn’t know what I was transitioning into, but it felt just as revolutionary.

**

On Friday 15 March 2019, a lone gunman entered Al Noor Mosque and opened fire on a large gathering of worshippers. He then continued to the Linwood Islamic Centre and carried out a second attack. There is no easy way to say this. Fifty-one innocent people were killed.

We were at Rita, in Aro Valley, preparing for a busy night of service when we heard the updates on Radio New Zealand. Each one was more horrific than the last as we huddled upstairs in disbelief. Each person deals with a moment of crisis in their own individual way. For me, I was overcome with a sense of urgency. In moments like these, I try to outrun shock and grief through action. Through keeping my hands busy with a frantic, manic energy. As a consolation, those things that are holding me back, all those niggly insecurities, those hesitations, are momentarily diminished. Four days after the attacks, there was a note on my phone that read:

Curry leaves

Pandan leaf

Mackerel

Dhal

Cinnamon

It was time to go to work. With the same effort with which I threw myself into a career in hospitality, I immersed myself in learning to cook the food I grew up eating. I stayed up late watching Anoma’s Kitchen on YouTube. Tested recipes on my days off. Phoned my dad. Phoned Grandma Seela.

Grandma Seela

The problem with Sri Lankan food is that it’s tricky to master. You can’t be heavy handed with volatile spices at your disposal. The wrong kind of curry powder can spoil a dish, just like a stale back-of-the-pantry curry powder can leave it muddled and confused.

What’s frustrating is when you know what it’s supposed to taste like but don’t have the skills to pull it off. And when it doesn’t taste right, which it often doesn’t, when you’ve added too much coconut milk and not enough cream or when you’ve burnt the cabbage mallum, you want to throw it in the bin and retreat to the comfort and safety of blended pumpkin soups and mince and cheese pies.

*

Kelda Hains, at Rita, taught us to cook without measurements, but cooking by feel requires secret ratios in your head ingrained from seasons of repetition. I had spent my whole career cooking other people’s food and amassed a nifty bag of tricks and tiny CV flexes that were useless for thinking about and executing my own cuisine.

Who knew that curries are boiled and not simmered slowly. That not every dish starts with sweating a brunoise of onion, carrot and celery in olive oil. That you don’t have to cook meat to oblivion until it disintegrates like a damp toilet tissue roll in your mouth. Who knew that goraka is a wicked souring agent similar to, but not the same as, tamarind. That the stems of green chillies contain the right bacteria to turn buffalo milk into curd and that curd chillies deep-fried in hot oil rule.

*

I hit a point where, fed-up by my lack of progress, I gave up trying to replicate and tried to make things as tasty as my hodgepodge abilities would allow. I had grown up at a table where the kim chi was next to the achcharu next to the carrot salad next to the crab curry next to the lamb stew. When I decided that I wasn’t gonna give people a crash course in Sri Lankan food or mansplain what it’s supposed to be, I was set free from my self-imposed obligation to authenticity.

Sometimes you have to be honest about your limitations and make them work for you. To that boy alone in the hallway feeling freakish in his own skin, you have to realise that which makes you different is inherently gorgeous. It deserves to be listened to.

**

Now that I knew what I wanted to do, I still had no idea how it would all come together. This is when Sal McMath came onboard. She used to work front-of-house at Rita and has a background in art history. The way we work is that she takes my erratic and half-baked ideas and turns them into coherent and tangible ends. Without her sensibility, her pragmatism, her sense of style and her mood boards, none of the pop-ups that we later went on to do ('Koryo' Korean Sunday lunch at Rita and 'Slurp Slurp' oysters, raw fish and natty wine at Puffin) would have happened.

SEELA is named after my grandmother, who, apart from being an amazing cook, is cheeky, rebellious and full of life. More than her food, it is these aspects of her character that we aim to showcase with the dinners. But just as much as SEELA is about my grandmother, it is about Sal and I. It is our response to everything that we feel is wrong about the hospitality industry. It is about breaking shit down – a reset. It is about building a community.

As much as I complain about the state of the hospitality industry and am cynical about its future, I am naïve about my attempts to try and change it. When there are people like Kelda and Paul Schrader, co-owners of Rita, who have been quietly building that community in Te Whanganui a Tara for decades, you gotta feel like there is still hope.

Two days before the start of the event, three churches and three luxury hotels were targeted in a series of suicide attacks in Sri Lanka.

SEELA poster

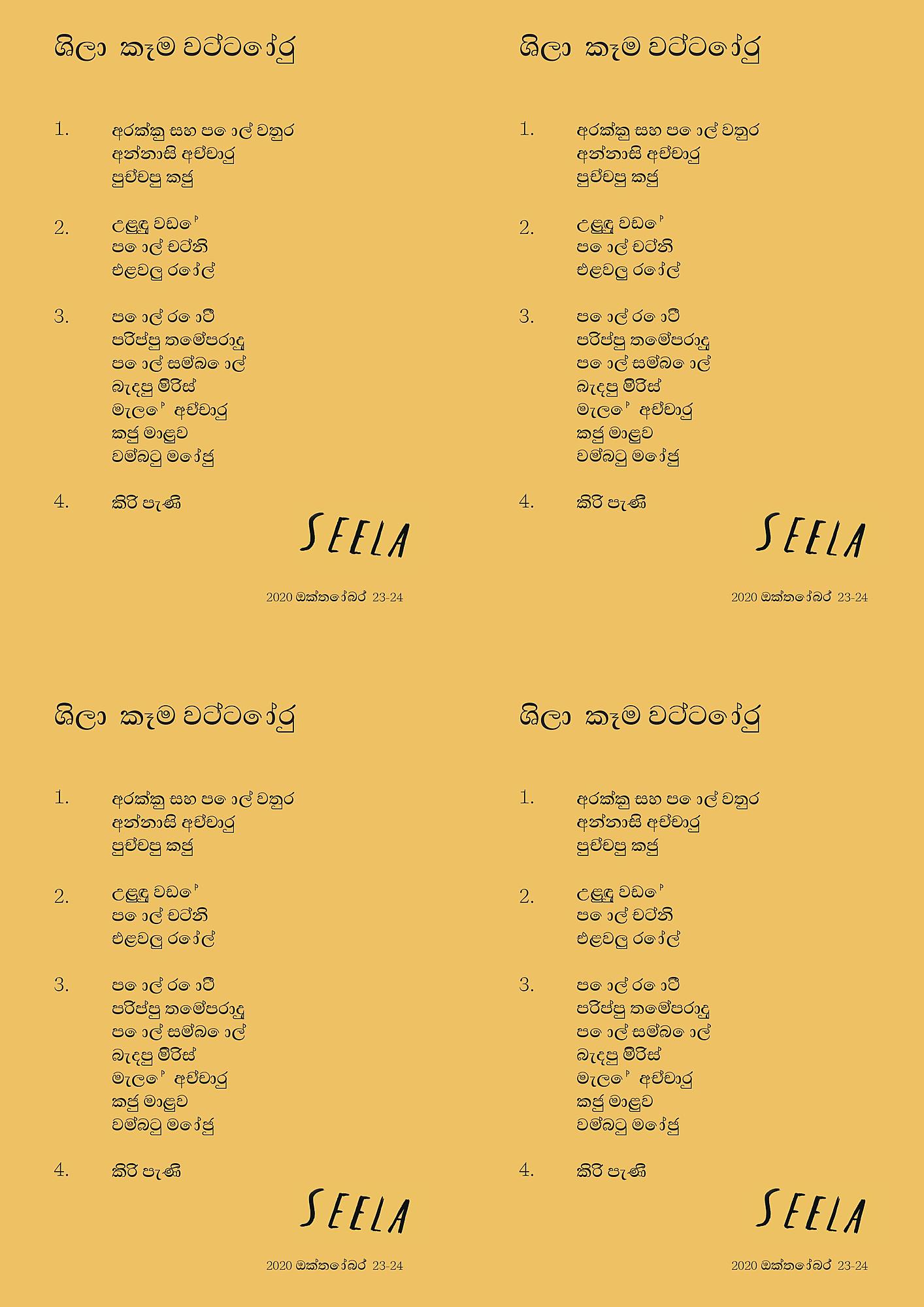

SEELA menu in Sri Lankan

We ran SEELA for two nights in April 2019 and donated all the tips and profits to the relief effort in Sri Lanka. Chinese-American chef Jenny Dorsey has a post on Instagram that says: “if you are going to profit from the cuisine of a certain group of people, what are you going to do to uplift that community so that everyone in it has improved access to opportunities in the future.”

*

We brought back SEELA a year later as an event under Wellington on a Plate and to the pay-as-you-feel dining concept Everybody Eats – tweaking it each time in response to the audience and our developing ideas. Thank you to those we have collaborated with, to Lily West for the posters, to Teresa Collins for the ceramics, to Briana Cleverley for the napkins, and Bumika for the ingredients. Thank you to everyone who has contributed their time, effort and energy and thank you to those we have been able to feed.

Out of certain moments of crisis and despair, you are left vulnerable, you feel targeted, ashamed and and alone. This was just one time I went, fuck it, this is me. This is what makes me different.

This is one for the Lankans.

One for the distant seaside.