SCUM and Bluebells: The New Poetics of Alice Birch

A manifesto exploding the legacy of language, Revolt. She said. Revolt Again. is an entropic hour of full-throated discord. Kate Prior explores the foundations and poetics of its unrest.

A manifesto exploding the legacy of language, Revolt. She said. Revolt Again. is an entropic hour of full-throated discord. Kate Prior explores the foundations and poetics of its unrest.

It’s 1973. We’re deep in the second wave. Feminist linguist Robin Lakoff writes a paper entitled Language and Woman’s Place. In it, she notes, ‘women experience linguistic discrimination in two ways: in the way they are taught to use language, and in the way general language use treats them’. The paper – the first of its kind to focus on gender and language in an academic field dominated by men – is greeted with controversy, and effectively launches the study of gender and language in America.

Since gender studies as a discipline only emerged in the 1960s and the study of language as relative to gender was established not long after, their development has been closely linked. A now common cornerstone of gender discourse (first introduced in the 1980s) is the notion that gender is not intrinsic to our biological sex – it is not something we are born with, it is something we do. Like gender, language is not benign – it shapes us and our world view, and the two are inseparable. ‘Language uses us as much as we use language,’ Lakoff writes. ‘As much as our choice of forms of expression is guided by the thoughts we want to express, to the same extent the way we feel about the things in the real world governs the way we express ourselves about these things’.

In 1980, Australian feminist Dale Spender followed where Lakoff left off, with her book Man Made Language. In it, Spender outlines the ways in which language that follows patriarchal patterns supports and perpetuates the subordination of women. She emphasises the fact that this patriarchal bias presents ‘male’ as positive or active and ‘female’ as negative or passive.

As a crystalline example, Spender looks at the names a group of scientists arrived at to describe the final results of an experiment. The scientists were looking for differences in perception when women and men looked at a certain stimulus in a surrounding field. The scientists found that females were more likely to see the item and its context as a whole, and males were more likely to separate the item from its context. When naming this phenomenon, scientists followed principles already encoded in the language (male = positive or active / female = negative or passive) and therefore named the behaviour of males as field independence and females as field dependence. As Spender notes, the descriptors for the same phenomenon could have taken the form of context awareness for females, and context blindness for males. ‘All naming is of necessity biased,’ Spender notes, ‘and the process of naming is one of encoding that bias, of making a selection of what to emphasise and what to overlook on the basis of a strict use of already patterned materials’.

Language uses us as much as we use language.

This led Spender to conclude that new names have their origins in the perspective of those doing the naming, and that perspective is the product of prefigured patterns of language and thought. She notes that new names systematically subscribe to old beliefs – they are locked into principles that already exist – and there seems no way out of this, even if those principles are inadequate or false.

*

Five years before Robin Lakoff published Language and Woman’s Place, radical feminist Valerie Solanas self-published the SCUM Manifesto. She then shot Andy Warhol and book sales went crazy. A radical man-hating tract (it is disputed whether SCUM was an acronym for the Society for Cutting Up Men), the manifesto subverts Freudian norms – those positive/negative codes – and draws the male as an incomplete female, lacking, because of that Y chromosome. Women, according to the manifesto, do not have Freudian penis envy, but men have ‘pussy envy’. Solanas declared that the only option for ‘civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females’ is to ‘overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex’. Taken at face value, the SCUM Manifesto is bonkers. Taken as a satirical literary device, it positions women as dominant in order to viciously parody a patriarchal society, by exaggerating accepted inequities in the extreme.

When commissioned to write a play in response to the provocation that ‘well-behaved women seldom make history’ (a quote from historian Laurel Thatcher-Ulrich), playwright Alice Birch did some reading and got angry. Part of this reading was the SCUM Manifesto, and it would appear that in Solanas’ text, she found a dramaturgical springboard – not only towards structure, but towards a tone of full-throated, messy rage. The series of vignettes, segmented by manifesto headings (Revolutionise the Language (Invert It) / Revolutionise the World (Do Not Marry), begins like a somewhat well-behaved comedy of (sexual) manners, only to dive-bomb into fragmented chaos.

It’s almost tautological to suggest that Revolt. She said. Revolt again. is a play about language. After all isn’t this true for all good plays? Don’t all playwrights emphasise or invert language – put the words up on display for our unpicking and analysis in this alternative stage world? Indeed, Birch sees it as the playwright’s role to pay special attention to our lexical tendencies. As she notes in a recent Guardian interview, ‘For me it’s the whole job. Language. Those are the tools. It’s quite old-fashioned. I take it really seriously’.

It makes sense then that Birch’s manifesto-of-sorts utilises language as its pivot point. The play takes as a particular focus those discoveries of the second-wave feminist linguists – Lakoff and Spender et al – testing and stretching them to sometimes hilarious and often devastating effect. It’s interesting (depressing? astonishing?) that while the intervening 40 years have seen shifts in some territories of our language (the widely employed non-relational title ‘Ms’ is a legacy of the second wave), there are other sections of the lexicon, often regarding sex, that if changed, would seem just as revolutionary now as then. It was Spender and fellow feminist Susan Brownmiller who noted that the name given to a particular act of sex – ‘penetration’ – offers a clue as to who created the verb, and that if the task of naming fell to women, it could just as likely be termed ‘enclosure’ (or any one of the catalogue of terms Birch throws up in the ridiculously funny first scene of the play).

The presence of bluebells in the text is at odds with the violence of revolt; their nostalgic quality teeters between comfort and the saccharine, their delicacy yet endurance is an antithetical pull against flux and uprising.

Birch peppers her text with recurring motifs (an ironically well-behaved lyrical tendency). They invade from the natural world; a motley collection of bluebells, watermelons and nightingales appear in scene after scene. Bluebells are as English as Cockney rhyming slang. The flower is an indicator species for ancient woodland – that is, woodland that has been around since at least 1600 AD. Because they have developed over such long timescales, ancient woods have unique features such as relatively undisturbed soils and rare, vulnerable communities of plants and animals that depend on the stable conditions of ancient woodland. The presence of bluebells in the text is at odds with the violence of revolt; their nostalgic quality teeters between comfort and the saccharine, their delicacy yet endurance is an antithetical pull against flux and uprising.

When indicating emphasis on certain words in her script, Birch turns them into honorary proper nouns by beginning each with a Capital Letter. It’s significant; it means that when you read the words as an actor, rather than the syntax suggesting SHOUTING, they are reinvested with almost symbolic importance. The familiar is made strange. ‘Spa Days’ becomes less about massages and more what the whole notion represents. The same goes for Chocolate Bar. Smiling. Happy Hour Mondays. In a scene about corporate complicity, the selected words become tiny building blocks of patriarchal capitalist oppression. There’s a phrase which Birch hangs at the beginning of each scene of the play: ‘I’m sorry, I don’t understand’. It’s something we say in foreign countries when we’re apologising for our lack of fluency. In Birch’s manifesto it appears because our mother tongue has been rendered alien.

*

It’s 2017. We’ve come a long way since second-wave feminism. Since then, prominent feminist voices like Judith Butler have introduced ideas around the performativity of gender, and bell hooks and others have crystallised growing discussion of the intersecting elements of race, gender and capitalism. Such intersectionality is now at the core of gender discourse.

But what of revolution?

Right at this moment in history a play called Revolt. She said. Revolt again. clearly takes on a bizarre congruity. America is in weekly Revolt. The demonstrations that took place a month ago in support of the Women’s March on Washington were the largest in US history, and photos from around the globe document a jaw-droppingly vast and vocal international movement.

It feels like our voices are loud enough to make change possible. That, and sometimes it feels like we’re shouting at brick walls. A friend recently posted on Facebook ‘I can't open any more links. I feel like 21 year-old me is shaking her fists at me and saying "This is it! The moment you've been waiting for! Revolution! Get there!" And current me is all "Oh hi, idealistic cutie. Thing is, I think we got carried away with the poetics of revolution. The reality on the cusp of fascism is bullshit and terrifying and so so sad’.

Perhaps if we grab the words and shake them out and stuff them with new meanings, perhaps if we suck all the air out of the useless ones and laugh at the rest, perhaps if we insist on exploding the language like Alice Birch incites, we can find new poetics.

Silo Theatre’s Revolt. She said. Revolt again.

is at the Basement Theatre, Auckland

15 February - 11 March

Tickets through iTicket

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Silo Theatre and appears in the show programme. Silo cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

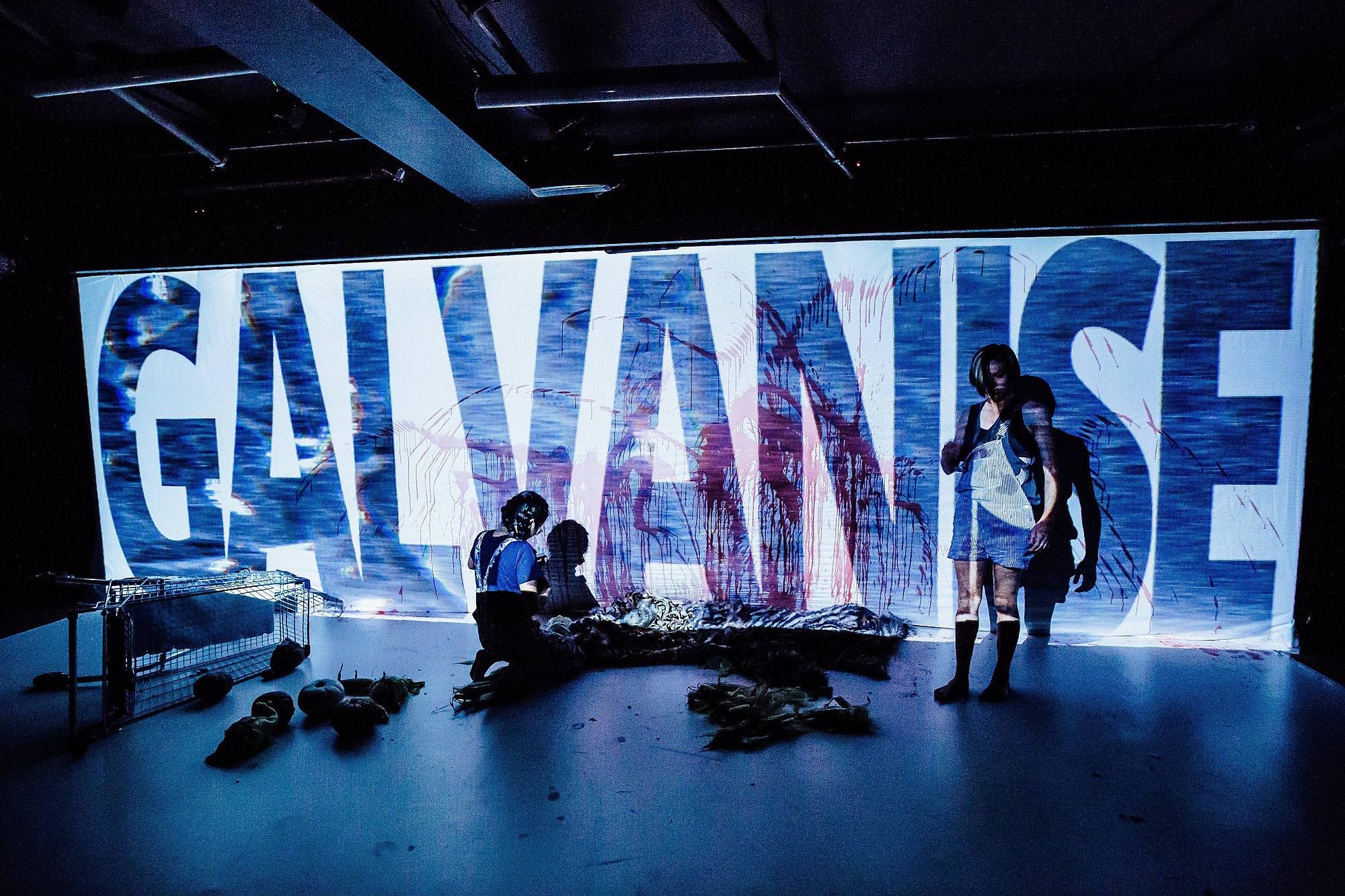

Images: Andi Crown Photography