Safety In Numbers: Poly Twitter and Carving Out Digital Space

Lana Lopesi on how the Pacific diaspora took to Twitter

I’m currently on my own, swatting mosquitos in a studio apartment in downtown Taipei. I’m surrounded by 7 million people in one of the most vibrant social and cultural centres in Asia, and yet I feel incredibly lonely. With no family or friends here, Twitter cuts right through the loneliness, and connects me with my online Pacific community as if I never left New Zealand. People either love it or hate it. But in moments like these, Twitter is a place of refuge.

We are amid a wave of self-publishing, and although people like to talk about how democratizing that is, it’s not necessarily concentrated among the young or the previously marginalised. You just have to read the New Zealand Herald comment sections, or Stuff Nation, to see that everyone has a voice online. Often, I can’t relate to the comments I find on places like these. Which is fine. But sometimes, I do want to log on to a safe space where I can be surrounded by likeminded people. For me that place is Poly Twitter.

Online spaces for marginalised communities preceded Twitter, and aren’t just confined to it now. Websites like Coconet who frame themselves as a “virtual island homeland” and even the private Facebook group Pacific Arts Cluster are both dedicated to creating spaces and dialogue about Pacific issues and culture. But Twitter’s true predecessor in terms of the opportunity to find your people and start immediate back-and-forth with them was the chat room. NativeNet, established by Hispanic-American Gary Trujillo in 1989-90 was the first global forum of its kind, a listserv founded to discuss Indigenous identity and culture that conincided with the internet first becoming publicly accessible. A decade later, sites like PolyChat and PolyCafe set up chat rooms for the Pacific community, home and abroad.

A decade on from that, you may have heard of Black Twitter. Recently validated by its own Wikipedia page, it’s the name attributed to the new digital space focused on issues of interest to the black community, particularly in the United States.

In 2015, a report by the Pew Research Centre estimated that 28 percent of African-American internet users use Twitter compared to 20 percent of White Americans. Further research indicates that 11 percent of those African-American users use Twitter daily, compared to 3 percent of White Americans. This meant that the sheer scale of African-American users on Twitter, in a greater proportion than virtually any other media space, gave the tweets of these users visibility to each other, linked through common threads and trends.

Experts are attributing the differences in Twitter uptake among different races to factors such as age and internet access. The median age of Black Twitter users is 7 years below the Twitter average. At the same time African-American smart phone usage is 44 percent higher than the national average. Sites like Twitter which, limited to a 140 character limit and continually refreshing, are more suited to and accessible on mobile devices than other social media platforms. Hence the uptake.

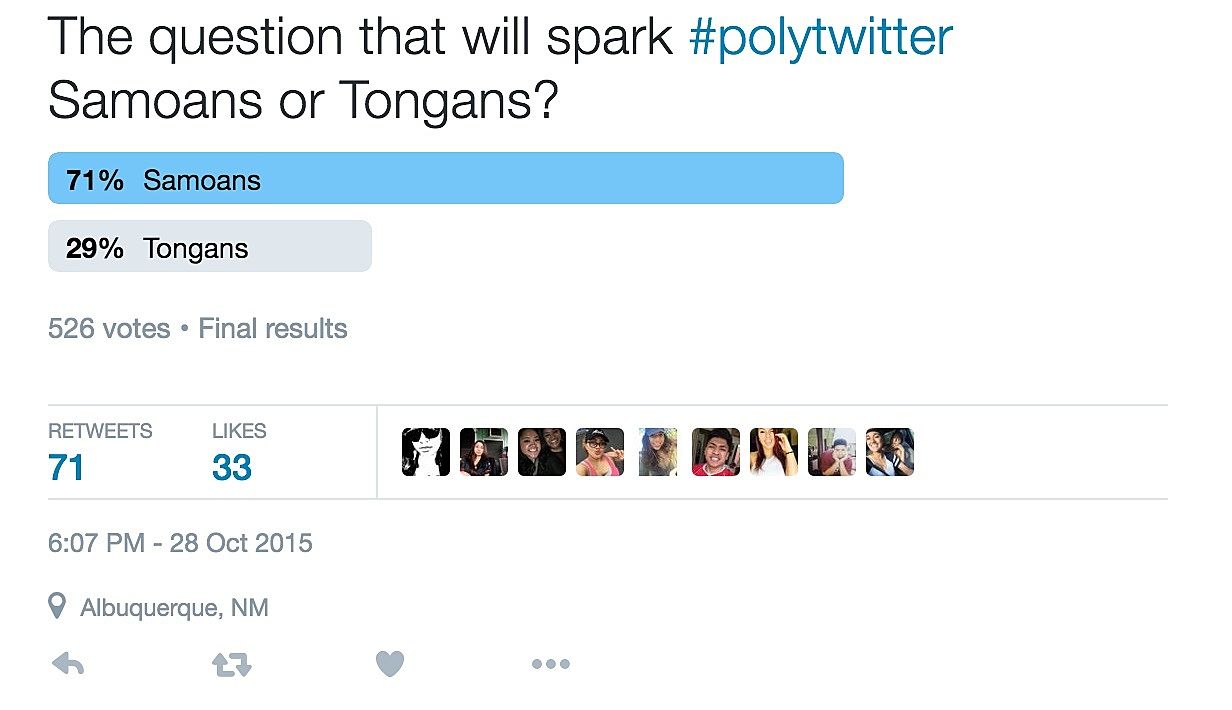

Likewise, Statistics New Zealand show that Pacific people are more likely to access the internet through their smartphones. Their data also demonstrates that New Zealand Twitter users are generally within the 18 to 29 age bracket, “seek real time interaction and news” and “are not as concerned about privacy as users of other platforms”. In 2006 the median age for the Pacific diaspora in New Zealand was 21 - compared to an overall median of 36. With the combination of these factors, it was only a matter of time before we noticed the prevalence of Poly Twitter, echoing some of Black Twitter’s demographic origins even as it forges a conversation entirely of its own.

Even for non-Pacific tweeters, Poly Twitter has reached a critical mass where it’s definitely visible to anyone who uses the site often. Put simply, it’s an online space focused on issues of interest to the Pacific diaspora communities, in NZ and elsewhere. While it’s impossible to find a single starting point for Poly Twitter, I can find tweets stemming back to 2012 using #PolyTwitter.

Among the more lighthearted discussions – memes and hashtags like #YouKnowYourePolyWhen, for example - are also conversations around what it means to be a Poly feminist, being gay or trans within Pacific communities, the role of the church, identity as a mixed-race person, and the impacts of colonisation that loom over all of these. No issue is too big or too small. More than just talking out these issues in the scope of 140 characters, Poly Twitter has its own style, fluidly moving between Pacific languages, internet shorthand and local slang.

The real question is - why are these cultural spaces forming on Twitter? It’s amazing what the digital realm has done for marginalised communities. A universal means of communication, platforms like Twitter are equalising spaces that cross race, class, gender and distance. You no longer have to be a published writer to be heard.

Twitter allows the Pacific diaspora from across the globe to connect daily without a need to ever meet. For scattered island nations with increasingly scattered expatriate populations, there is now a strength in numbers. Reunification through Twitter is allowing for a redefinition of identity with digital mass. With that comes the use of Twitter to rebuild cultural values from the inside out. Ironically, the greatest tool of globalisation — the internet — is finally helping marginalised communities to reinforce culture.

The idea that Twitter users can seek out direct contact with people who are likely to share and appreciate their life experience means that there is no fear – compared, for example, to speaking out on a blog’s comment section. It is a powerful tool for fighting colonial and oppressive attitudes - the perfect place for Indigenous cyber-activism, as you may call it.

I consider myself very fortunate to be a writer. I have avenues for publishing my social commentary and thoughts. But unfortunately for the Pacific community, that opportunity is rare. There are very few Pacific commentators within formal publishing, and spaces such the New Zealand Herald that position themselves as the mainstream voice of the country largely fail to reflect the Pacific proportion of the population. Of course, people like Leilani Momoisea (Radio New Zealand, Metro) or Leilani Tamu (Metro, Spacific and Landfall) are refreshing exceptions to the rule. Although it is worth noting that both Momoisea and Tamu, have backgrounds in self-publishing and have had to supplement their writing with other work.

So I take my hat off to those active on Twitter for keeping us all informed and accountable just by voicing their opinions. If you take the time to read the threads, a lot of these smart, informed and empowered people are writing some of the best and most relevant social commentary.

Recently, I wrote on here about Tanu Gago’s work and its parallels with Beyonce’s music video for ‘Formation’. That video clip went viral, more so when it was followed by a half-time Superbowl performance. The video tried to encapsulate a sense of Blackness exclusive to the Southern parts of America, to huge acclaim and controversy.

The video was a provocation everywhere, and Poly Twitter was no exception. It went crazy with a whirlwind of thoughts and opinions, and brought up conversation points I hadn’t even thought of, all of which were specific to a Pacific viewpoint. For me, the key thread was a conversation about how Pacific women can support the struggle of African-American women, but to remember that for all its experiences, our culture doesn’t stem from slavery - to acknowledge our differences even as we see resemblances.

Between when I had submitted my first draft and when the editor came back to me, Twitter had already taught me just as much to modify it, clarifying my thinking with a smart, succinct consensus.

I don’t know where to find such nuanced public conversation from a global Pacific perspective outside of Poly Twitter (if it does exist). And what these fiery, smart, brown people tweet, often the media themselves can not ignore.

Take Eliota Fuimaono-Sapolu (@Eliota_Sapolu), a name that resonates beyond Poly Twitter (21.6K followers and counting), and of course, beyond Twitter itself. The Samoan-born rugby player made New Zealand news during the 2011 Rugby World Cup when he called one of the referees racist and bigoted on Twitter.

While he suffered repercussions for that particular tweet (a suspension from rugby – and therefore a deprivation of livelihood for him and his family – for six months), he has been instrumental in vocalising corruption among the Samoan rugby union, and the treatment of “second tier” developing nation rugby teams.

More recently you may recently have read a string of articles relating to Richie Hardcore and his comments about female sexuality online, like this one or this one. What many of the articles don’t tell you is that it was Leah Damm (@beingahouse) who initially sparked the conversation on Instagram then moving onto Twitter with a series of powerful, critical tweets (in fact, her commentary on virtually everything from motherhood, politics to current affairs is fearless and informed).

In its short, easy to digest but often challenging tidbits, Poly Twitter is becoming a form of journalism with an instant readership. The ability to go direct to source, without any filter, provides both candor and sincerity. It gives people the platform to speak without having any lens placed on them and without their argument watered down.

Researchers have expressed concerns that the Internet will act as a tool to further the process of Western acculturation for Indigenous people. But that’s a process that’s already taken place for centuries, generally by force. Instead, I would say that the strength of Poly and Black Twitter as a small sample proves how Indigenous and diaspora people have appropriated the medium of the internet for their own purposes.

Social media has both destroyed and recreated how we talk to each other. Currently, it’s proving to be empowering, giving groups a voice who may never have had one generations ago. People say that we edit our social media to reflect our own worldviews – following and unfollowing people who we do or don’t agree with. Whether that’s the case or not, I do know that right now, my feed is very loud and very brown. I’ll keep it that way.