Riding Imperfect Waves

Kerry Ann Lee sees the joy of everyday life and mother–daughter relationships in Claudia Kogachi’s exhibition There’s No I in Team at The Dowse.

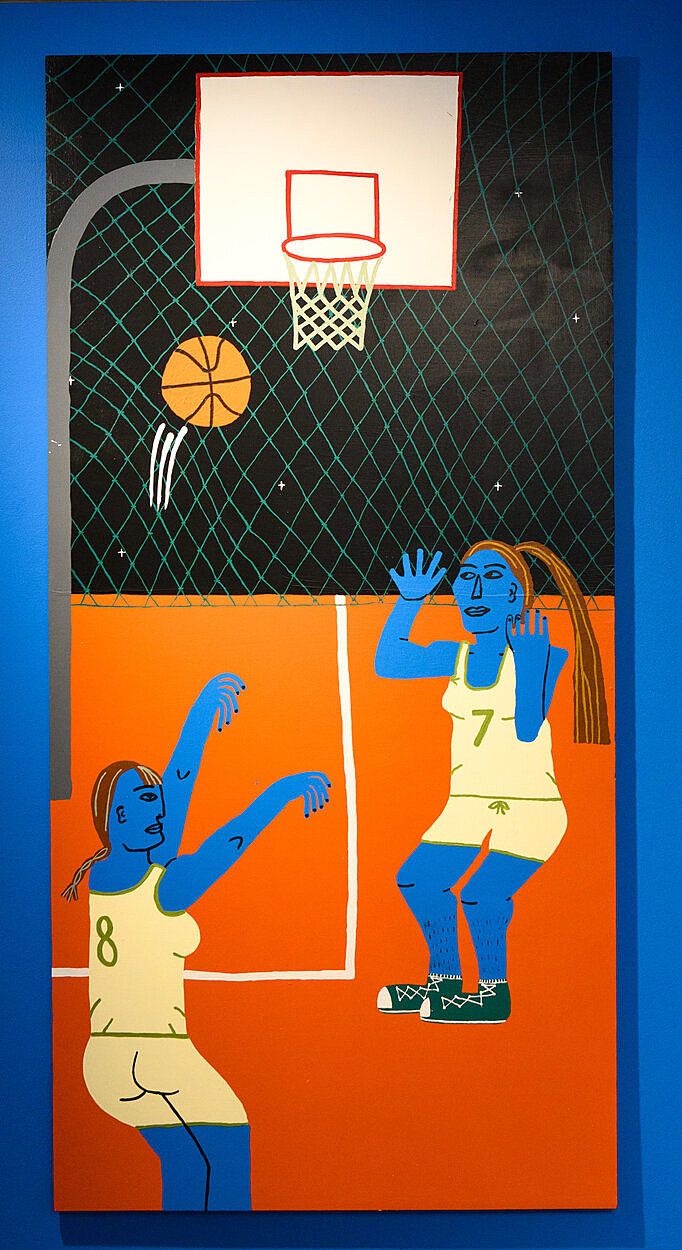

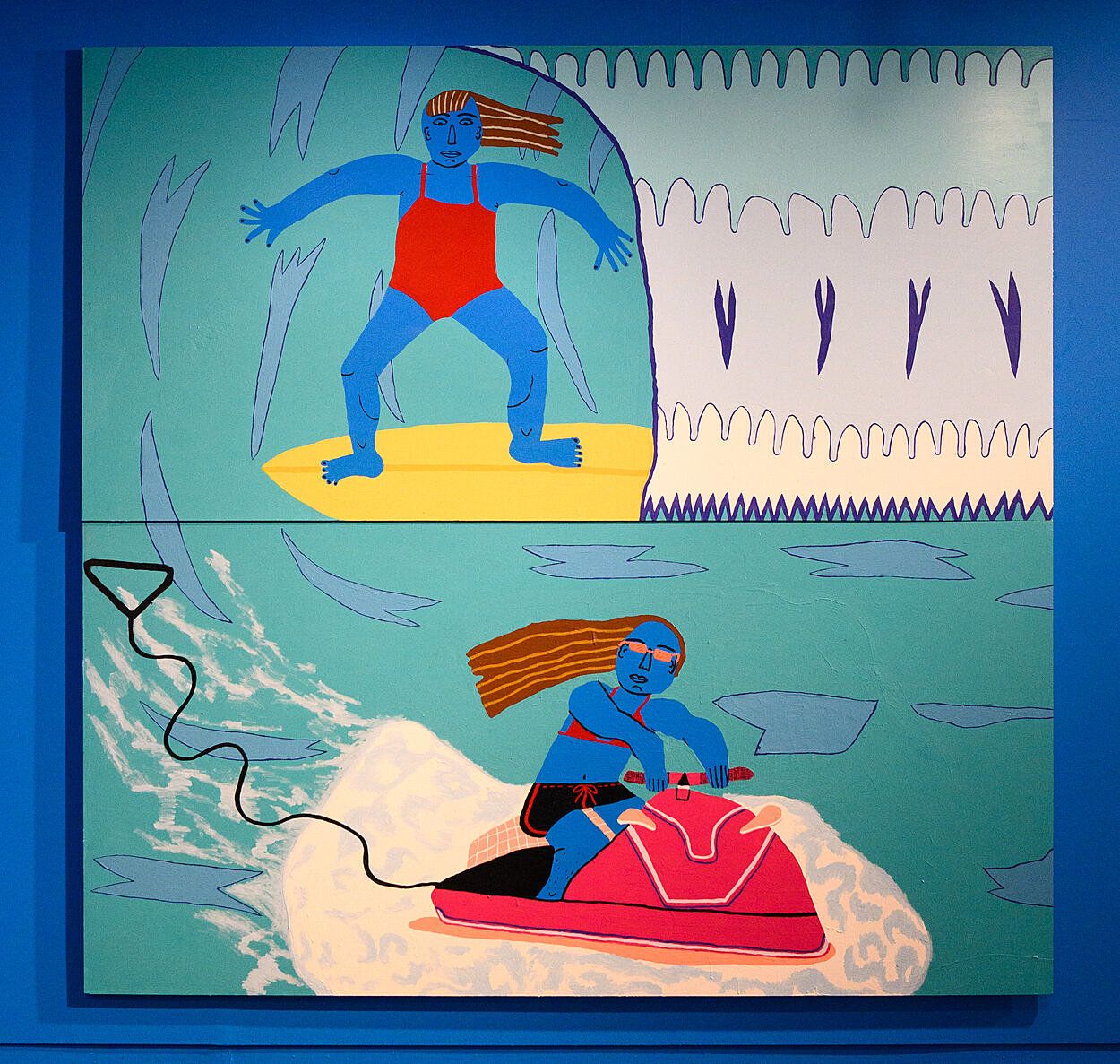

Broad-brushed lines reveal determined faces with an eye on the prize, exposed elbows and kneecaps; beach babes swoop over scattered shells at sunset, wispy whitewater clouds, chunky-cut waves, b-ball beneath a starry night sky – nothing but net. Welcome to Claudia Kogachi’s world. Over the past few years, Kogachi has been making and exhibiting artwork that appeals in both visual content and approach. Lush hand-tufted rugs depicting domestic scenes of her Japanese grandparents’ lives in Hawaii and a memorable show featuring assorted characters dealing with head lice, fly and mosquito infestations and the like. There’s No I in Teamis about mother–daughter relationships. Kogachi’s in particular.

For this exhibition, Kogachi’s collection of large, wall-sized acrylic paintings on plywood live in an electric-blue room upstairs at the Dowse Art Museum. The wall text explains that Claudia and her mom are depicted as “wonky blue figures playing a range of popular sports”. Shape, line, colour and movement fill up my eyes and evoke feelings of simple joy inside the blue room. These are figurative forms in flat space. Two bodies per painting. Catching, throwing, hitting, swimming and riding things. Activities that I don’t do much, growing up mostly as an indoors kid, but which I admire in others who do. And good timing, too. The exhibition has been on during the recent Tokyo 2020 (really 2021) Summer Olympics, a popular sedentary pastime for many fans who watch and cheer on champions of these sports on TV.

Claudia Kogachi, Golf, 2021, The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography

A surface reading of Kogachi’s paintings as pop or naive misses out on other critical dimensions. The exhibition text goes on to say that the show is “a psychological portrait, warts and all [about how] upbringing, culture and identity shape our family experiences.” The diptych paintings are composed of 50/50 divisions that emphasise the flatness and the deception of an ‘even playing field’; however, as a visual storyteller, Kogochi crafts her work to invite open interpretations. Golf is particularly eye-catching, with 50 percent texture and 50 percent flat. A speckled ball rolls across macaroni turf towards the viewer. Mom (?) looks on proudly (or possibly peeved) while Claudia (?) goes in for a hole-in-one. Two older gallery visitors behind me vocalise my thoughts: “But which one is mother, and which one is daughter?” (A clue is in Tennis).

The fact that this is a mother–daughter story is intriguing, and I imagine it would be appealing to gallery-goers, some of whom might even be made up of mother–daughter teams (MDTs). But what do I know? Mother–daughter stereotypes don’t tend to be kind. From the bossy mother-of-the-bride, doting stage mothers or the dreaded tiger mom (and who can forget teen mom or wicked step-mother). Ai-ya! So much drama! The very thought of MDTs elicits feelings of embarrassment and many face-palms, not for individuals per se but for a society that continues to perpetuate such cruelty towards mothers and daughters in popular culture.

I’m at an age where I’m drawn to learning more about the actualities of parenthood. My friends have kids and are swiftly learning what motherhood and fatherhood looks like in various guises, past the shitty stereotypes towards something real and good. I respect the selflessness required just to make sure their kids are happy, breathing and okay. It sounds so simple from the outside, yet this love is hard work. There seems to be an obvious labour aspect to parenting (including the actual prenatal and giving birth part). So what of leisure? Claudia Kogachi’s choice to depict her relationship with her mom through playing sports is a humorous yet sincere approach towards offering up new ways of thinking about such a relationship.

Mother–daughter stereotypes don’t tend to be kind. From the bossy mother-of-the-bride, doting stage mothers or the dreaded tiger mom... Ai-ya! So much drama!

Claudia Kogachi, Basketball, 2021, The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography

I imagine that parents would see aspects of themselves in their kids, either working with or pushing against societal and cultural norms and conventions. It’s not always equal, either. There are mothers and daughters – or parents and kids – who play well together and others who don’t. Arguments and emotional battles go on without an endgame, sometimes for a heated moment, others over a lifetime. Often the past of least resistance would be to describe such relationships as ‘complicated’.

Amidst spoken and published wisdoms, I’ve come across a few insights. Rad Dad: Dispatches from the Frontiers of Fatherhood features essays written by dads from different walks of life that explore parenting as political territory, while The Mothers Who Made Them: Reflections from mothers of creatives, curated by Ruth Corin with artwork by Isla Treadwell, is a zine I recently picked up from Strange Goods. In The Mothers Who Made Them, the question is asked: “What has being a mother taught you about yourself and the world?” A few responses stood out, such as Ioana Parker’s, “That it is OK not to be perfect'', and Lisa Clarke’s, “I guess it shows me my limitations – my humanness. Quite humbling I guess”.

Claudia Kogachi, There’s No I in Team (installation view), 2021. The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography

Kogachi’s ‘team-with-no-I’ is an idealised kind of personal relationship. It contrasts with the psychologically lit scenes of female-centred domestica painted by Jaqueline Fahey from a different era, depicting mess, quarrels and discord exploded all about the house. In Kogachi’s world, there is no clutter. Sun, sand, surf and turf are all that’s required, and everything has a place. Yet imperfection is visible through the hand of the artist. Kogachi’s paintwork is deliberately thick and unapologetically applied. Although compositionally flat and balanced, closer inspection reveals crunchy, uneven surfaces. These “spits and spats”, as my artist friend Tom Sladden calls them, are things viewers relish and enjoy that connect them directly with the artist. They’re akin to the audible breaths that singers take within their songs (listen to Motown recordings of Diana Ross and the Supremes) to show that they’re alive and breathing, just like you.

Claudia Kogachi, mural in There’s No I in Team, 2021. The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography

The tactility of these gestures and textures is evident in Kogachi’s tufted rug works, designed to be touched. For her show at The Dowse, interactivity comes in a collaborative community mural project, also inhabiting the same space. Kogachi’s line drawings across three walls are giant colouring-in pages for parents and kids of all ages to work with. Within this seemingly twee activity is the gold from which seeds of nurture are planted – to encourage each other to draw, colour and make art. What little I know about art and parenting, from those around me, has a lot to do with taking risks and embracing imperfection.

Claudia Kogachi, mural in There’s No I in Team, 2021. The Dowse. Photo: Kerry Ann Lee

Kogachi’s work is autobiographical, touching on fantasy. And why not? Artists go where others don’t to yield new insight into our beautiful, boring, everyday lives and show what is possible. I’m currently sitting on a giant tennis ball in the exhibition space as I am writing this, by the way. This spatiality is an exciting prospect with these flat, graphic pieces reading together as an installation. This is evident in Body Surfing, featuring two figures that appear to spring from the same wave, swimming out in opposite directions across the adjoining walls. The format is reminiscent of her smaller corner work of two backgammon players getting sassed by cockroaches, shown at Jhana Millers Gallery early this year.

Kogachi’s work is autobiographical, touching on fantasy. And why not? Artists go where others don’t to show what is possible

Claudia Kogachi, Tow in Big Wave Surfing, 2021, The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography

Kogachi’s affinity with Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa comes from being born in Japan, growing up with her mother’s side of the family in O‘ahu, Hawaii, and now living in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. My favourite painting is also ocean-themed. The top section of Tow in Big Wave Surfing features mother (or daughter) surfing, while the bottom is the daughter (or mother) jet skiing. Again, who’s who is irrelevant. Or, if we believe that it’s the same frame with foreground and background, the two characters masterfully ride across each panel, triumphantly ruling the waves together.

O‘ahu was also once home to Princess Ka‘iulani, niece of Queen Lili‘uokalani and last in line to the throne of the Kingdom of Hawaii. As well as being a young poet, musician and painter who kept company with other artists, Princess Ka‘iulani was also known as “the mother of modern surfing”, helping keep the tradition of surfing alive in Hawaii during rapid European colonisation. She was believed to be the first female surfer in the UK, residing in Brighton just before the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown in 1893 and annexed to the US in 1898. "I love riding, driving, swimming, dancing and cycling. Really, I'm sure I was a seal in another world because I am so fond of the water,” she shared with The Sun in 1897. “My mother taught me to swim almost before I knew how to walk.”

Amidst the hardness and the struggle, what about fun and women’s desires as we get older? Mamas in particular. I’ve often heard from older friends about becoming more ‘invisible’ as you age. Therefore I look to examples of ordinary existence as forms of resistance, by those who write their own narratives. Like Moe Bowstern, fisherwoman and “tough cookie”, whose zine Xtra Tuf chronicles her life and times in the male-dominated commercial fishing industry of Kodiak Island, Alaska. Or in drawings and paintings by the late Margaret Killgallen of cool older women who played the banjo or swam great lengths in woollen swimsuits. Perhaps that’s why I warm to the folksy toughness of Kogachi’s characters. I find them akin to those found in the art of Esther Pearl Watson, and Saskia Leek’s early comic-inspired works. Painted people who bend and wiggle, pant and sigh, sometimes with funny clothes and big hair, and are unashamedly getting on and ‘doing life’ in the great wide world.

Claudia Kogachi, There’s No I in Team (installation view view), 2021. The Dowse. Photo: Kerry Ann Lee

Might such approaches to authorship and legacy be useful to consider in the art game, with its pageantry, competition and fandom, and the sliding scale of success and/or bitter defeat – depending on your standards? I’m reminded of proud parents covering their kitchen fridges and office cubicles with their kids’ drawings and encouraging them with extracurricular activities. I sometimes meet them when they come through for design school open days, or four years later at graduation. Parents who, despite their own fears, try their best not to cast doubt or judgement on their kids, as the world has enough of that to go around. I also know folks who grew up with very little support and understanding and plenty to push against, but did it anyway. Some of these people are parents themselves, determined to write their own rules.

How about all those unbillable hours that parents spend taking kids to sports games, exhibitions, concerts and events to promote an interest in the world? Beatle Treadwell’s response (in The Mothers Who Made Them) to what motherhood taught her comes to mind: “Everything is a phase. It’ll be something else next week. As long as they’re alive, everything will be okay.” The content of Claudia Kogachi’s paintings reminds me of rare holiday snapshots capturing an assortment of joyful phases that I and those around me go through, not just as kids, but as adults. Somehow such precious moments of playtime get swallowed up by the busyness of everyday life, yet still bubble up, like in the company of Kogachi’s work. Her oversized illustrations exude a certain kind of love – an ideal of a relationship that many may never have, or might manifest in a multitude of other weird ways.

*

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Feature Image: Claudia Kogachi, Body Surfing, 2021, The Dowse. Photo: Mark Tantrum Photography