Twenty-One Shows From The New Zealand Fringe Festival 2016

With the New Zealand Fringe Festival wrapped for another year, seven Wellington theatre-makers talk about the 21 shows that grabbed them the most.

With the New Zealand Fringe Festival wrapped for another year, seven Wellington theatre-makers talk about the 21 shows that grabbed them the most.

The New Zealand Fringe Festival’s near-destruction in the late-2000s seems a world and a century ago now. This year, the Festival premiered 150 shows - theatre, music, dance, improv, cabaret, art, and everything that blurred the lines between them. Pantograph Punch sent seven Wellington theatre-makers along to over half of those shows. Their thoughts on the Festival as a whole will be published next week; for now, here are the twenty-one shows that hooked them - for what they were, for what they could be, and for where they and their makers could go from here.

(Editor's Note: Because Wellington is ridiculously small, there are four identified conflicts in this piece pertaining to shows writers were directly involved in or their loved ones were directly involved in. In all cases, the writers involved removed themselves from the decision-making process around that particular show. All reviews were written independently by each individual writer and vetted by two different editors.)

Adam Goodall

We spend most of Wench's and then she let herself go with our eyes closed. Guru Rach (ex-Binge Culture performer Rachel Baker) leads us through our first experience with the ‘cosmic ocean’, but she needs us to follow her instructions, starting with our eyes, closed. Guru Rach is preoccupied with controlling her space and Baker and her director, Isobel Mackinnon, constantly play with that control. Rach describes images designed to to help us meditate and in so doing hands control of the show’s visual life over to each individual audience member. It’s a bold move, giving us room to drift, but Guru Rach keeps pulling us back with descriptions that feel and look like dreams with an uncomfortable basis in reality. Baker keeps pulling us back into the complicated psyche of a woman trying to hide her insecurities by projecting ultimate control, but she also lets us project our own worries onto Guru Rach by handing the audience that unique degree of control over how that psyche looks and lives. That’s where and then she let herself go is at its most fun, its most thrilling, its most triumphant: it embraces the power and vulnerability of closing your eyes and letting yourself go.

Destiny’s Child’s Survivor was the first album I ever owned (Christmas present, 2002), so Tasha already has me on side when she starts gushing about her “BFF Beyonce”. Tasha’s a gregarious legal secretary from Upper Hutt telling us her life story (as filtered through her time in the Beyhive) from inside a half-full bathtub; as played by Rose Kirkup, she’s gossipy and confident and has the vocab and aspirations of someone who moved out of the Hutt but never really left it behind (“I got an apartment on Courtenay Place,” she brags, “four minutes from Les Mills, so I was maintaining”). She drops pop culture on us like a bad habit and talks like everything she says should be obvious to everyone. Her routine is charming and well-constructed and obviously a way for her to hide the fractures in her life, but Tasha Fierce never talks down about her. There’s a rich vein of compassion for Tasha and her fandom, celebrating the million little things in everyone’s past that follow us into the present - the places we live in, the friends we make, the music we love. It’s also compassionate enough to refuse to pull punches, and Tasha Fierce’s greatest achievement is its honest and blunt portrayal of the pressure the world puts on us to leave our pasts behind, and the hurt that pressure causes.

Surrounded by a ring of flour, Ian Michael lets us know that we “might not be able to pick between peoples’ voices.” HART’s a verbatim show built out of interviews with four generations of Aboriginal men who lived through the Stolen Generation and its aftermath, and their experiences, Michael warns us, might be hard to pull apart. The stories are different, but the pain is universal.

HART’s style of documentary theatre has an inherent value, giving a platform to people whose lives have been distorted and voices have been silenced by the status quo, and Michael and co-writer Seanna van Helten don’t squander that. They move between the four interviews with care, echoing and juxtaposing each man’s testimonials to build a deeply harrowing portrait of pain and loss born out of white Australia’s racist violence (both on an interpersonal and a federal level).

At a brisk 45 minutes, HART doesn’t go as deep into the experiences of its interview subjects as it could, and Michael could follow through on his warning. The script’s constructed to emphasise the echoes, the collective experience of this pain, but Michael portrays the interviewees with clearly delineated physical and vocal identities, foregrounding the work’s theatricality and the ‘embodiment’ of the interviewees at the expense of highlighting the things that unify them: the struggle, the anger, the scars. That doesn’t mean HART’s not a powerful and affecting piece of documentary theatre, though; it is, a righteous and surprisingly visual call to action against the racism and condescension that still causes harm to indigenous communities today.

Ania Upstill

Perhaps, Perhaps...Quizás was the only show in the Fringe that I saw twice, compelled to re-experience a performance that was perfectly planned and yet deliciously open to change; while the narrative arc remains consistent, Gabriela Munoz, playing a lovesick clown, tailors each performance to its audience. Perhaps, Perhaps... Quizás starts by showing us Greta’s dreams of marriage. She’s comfortable and safe until she – and Munoz – takes a risk by inviting audience members to join her onstage. From there, Munoz balances the audience and her ‘husband’ of the night. A highly skilled clown, Munoz varies her tempo and energy from the first minute, inviting the audience’s laughter and astonishment. Her physicality and her amazingly responsive face – highlighted by quirky makeup, including a perpetually quizzical eyebrow – are delightful and enchanting, taking us with her as she bares her clown's soul, audaciously exposing dreams and insecurities. The material isn’t new (Munoz has been touring this show for five years), but her vitality as she returns to it fresh each night is a gold standard for exquisitely-crafted clowning; it revived my belief in theatre’s ability to affect hearts and minds.

Pat-a-Cake Productions’ The Trickle Down Effect takes on a complicated and urgent idea and presents it in an elegant and thrillingly physical way. Instead of loading down the audience with statements or statistics, Pat-a-Cake explores multiple angles of the basic fallacy that money from the rich will 'trickle down' to the poor (and thus that tax cuts for the rich lead to a more equal society) entirely without words. Pat-a-Cake’s use striking physical images - the four actors interact with four shower-heads sprouting from a central point on the raised stage - in place of words, letting them speak for themselves. . The performers work in clown, creating naïve characters that are easy to empathize with because of their clear emotional availability and vulnerability. It’s heart-wrenching watching some struggle to gather water ('money') from the shower-heads while others bathe in an unending supply, knowing that whatever is causing the flow of the water, or lack thereof, is clearly out of their control. Energetic and playful, the performers tackle these issues without telling the audience what to think.

In Why Do I Dream?, a comic blend of performer Sabrina D’Angelo’s personal narrative and the narrative of Madame Bovary’s titular heroine, D'Angelo demonstrates impressive ingenuity and virtuousity. Creating a world that is both highly humourous and full of wonder, D’Angelo transforms herself and her props in front of the audience’s eyes. A balloon turns into a character's head, an apple eaten by a worm becomes an emblem for mortality, a scarf turns into the plastic bag from American Beauty. D'Angelo demonstrates her bravery and generosity as a performer throughout, checking in directly with the audience. She uses eye contact, physical touch and cupcakes ensures that we’re all buying into her fantastical journey exploring the absurdity of the human condition, and that we’re all along for the ride. Further, D'Angelo’s clearly spent a great deal of time tailoring her jokes to appeal to a wide range of audience members, unafraid to be self-deprecating or even lewd: even my small Wednesday night audience was rolling with laughter.

Baz Macdonald

Primarily using clay to communicate with the audience, Carroll's incredibly innovative Layman illustrates the development of its title character as he discovers his own humanity and sexuality. Carroll’s clay is integral to Layman’s deeper messages about who we are and how we develop; he uses the clay to change and adapt before our eyes, condensing a lifetime of physical, emotional development into mere moments. Through this, Carroll demonstrates his mastery over both the clay and his own body, combining the two until they’re almost indistinguishable from each other: the faces Carroll carves into his clay mask, for example, are straight out of a Guillermo del Toro film, beautiful yet disturbing. Layman is an superbly crafted production with a thought-provoking narrative and a nuanced performance at its centre.

Watching Dorge felt like the theatre equivalent of watching The Beatles play at a dive bar in Liverpool in the early 60’s. This is the start of something important. Dorge, with his puppet master Jon Coddington introduces the people of Wellington to some more... fringe sex acts from around the world in his ABCDS&M, and as a character, Dorge is a fascinating mix of deviant and adorable. The balance clearly disarms the audience, making them not only comfortable with the risque content and innuendo but eager for participation: in only half an hour, Dorge had women comfortably letting him nestle his furry face in their cleavage and men comfortably putting their hands on the back of his orange head as he simulated fellatio. Surprisingly, this content doesn’t come off as seedy or lecherous, but rather as a celebration of sexuality and fringe sex. It’s easy to forget because the two are such different personalities on stage, but Dorge is successful because of Coddington’s improv and puppetry skills, skills so immense that it’s often hard to remember he and his puppet are one and the same.

Even though its five nights in Fringe were explicitly a development season,I, Will Brown is still a truly evocative one man show. Eamonn’s exploration of his complex relationship with the coolest kid in his primary school is a fascinating and, as personal as it is to Marra, ultimately relatable tale. Eamonn’s performance is deeply honest, often feeling like an off-the-cuff conversation about his life stories. It’s easy to get lost in and forget you’re watching a crafted narrative - then you see the threads of the story all pulling together and you realise just how well-constructed Marra’s work is. His script and performance are so subtle and truthful - he’s not afraid to make himself look vulnerable, talking about subjects as deep-seeded as body issues and feelings of self-worth and inadequacy - that even when things become surreal you second guess if this isn’t his reality after all. That storytelling makes Marra’s talents as a comedian clear; he uses self-deprecation well, endearing himself to the audience and ultimately revealing truths about himself and his story. It’s the kind of story and performance that sticks with you for days, playing on your mind and prompting you to reflect on its connections to your own life.

Hannah Banks

Last Meals: A Nine Course Buffet

Nine women, all on some kind of fictional/global death row, come forward one by one and tell their stories. As a first play by a promising writer, Last Meals is very good, even, at times, brilliant. The more subtle and surreal monologues, the ones that manage to contain both darkness and comedy, are excellent: Pinot Noir’s repetitive list of her daily actions, Tic Tac’s ominous counting, and Spaghetti Bolognese’s slow reveal of her crime, which Jean Sergent performs with perfectly malicious joy. Director Ben Emerson enhances these successful moments with some lovely choral work and some interesting interactions between the different characters. However, the tone is uneven and relentlessly dark; because of this, the actors and characters who lighten the load with some comedy really stand out and are far more effective. Further, some of the monologues are repetitive, hitting the same note throughout (and Salami Stick’s thick French accent makes hers difficult to even understand), and could easily be edited for time or cut. There’s so much potential in this production and seeing nine women on stage is wonderful, but quantity takes priority over quality too often.

They had me at laughing labias. The Offensive Nipple Show is an absolute riot and everything I want in a Fringe show: it’s provocative, thought provoking and moving. The design is simple and effective and Bop Murdoch’s direction is fluent and engaging. Moreover, Bates’ gift with words and Tuck’s comic instinct combine to create an electric atmosphere; together, they tackle a lot of difficult topics, but that’s part of its success. Their broad scope (they cover body sovereignty, reclaiming nudity, breast feeding, rape culture and more) provokes questions while never offering neat answers. It wrangles with feminism as a massive body of complex ideas, creating a platform for discussion rather than following a traditional, climactic narrative approach. The Offensive Nipple Show is doing something alternative and magnificent with its structure and underpinning philosophy, and while some of the individual pieces are unclear in their intent and in their contract with the audience on opening night, it’s still a joy to watch. These two performers are magic together and the conversation that they’re starting is absolutely vital.

Sameena Zehra - Homicidal Pacifist

Sameena Zehra is a pacifist with a culling list and she is violently delightful. Zehra has examined the current state of the world and believes that the only way to fix things is to cull certain offensive members of the human race, a difficult thing to do when you’re a lifelong believer in non-violence. So, she’s created a culling list so she can discuss her anger with her audience before she actions it. What follows is 60 minutes of fast-paced and fluent comedy where Zehra swiftly steps between politics, racism, sex, terrorism, homophobia, feminism, religion, and planning her husband’s funeral. This seems heavy but Zehra’s warm and inclusive delivery keeps her audience in stitches. Even when she’s attacking a despicable politician or her own difficult mother, she does it with charm and intelligence. She returns to personal stories to illustrate wider problems, keeping the audience on side every step of the way. This is intelligent, political comedy at it’s absolute finest: furious and beautiful, frustrated and empowering, with just a little bit of hope at the end.

Hilary Penwarden

Created by The Great Danger (Freya Daly Sadgrove and Callum Devlin), CITIZEN is a touching yet confronting Kafka-for-millennials. In Citizen’s dystopian world, anyone who wants to remain alive after their twenty-first birthday must complete an application for permanent citizenship. Citizen Number 919933007 is appearing before us to make hers. CITIZEN is a deeply personal show for Sadgrove: in it, she desperately attempts to qualify her life with real-life school reports, certificates and degrees. She’s open with her intimate material, listing countless achievements (ordinary and extraordinary) in a breathless monotone that keeps the atmosphere tense. But Sadgrove’s also funny and disarming and she exercises a wicked deadpan, and Callum Devlin skillfully balances her energy out with his calmer demeanor. He’s a dynamic presence and his ability to draw the narrative out from its dystopian framework to the here and now stops the show from becoming a vanity project. Together, they convince us to give them our hearts, but it soon becomes clear that they don’t know what to do with them. Sadgrove’s vulnerability is devastating and beautiful when it’s allowed to breathe, but as CITIZEN builds to its climax, her deadpan asides and flippant one-liners undermine our emotional investment. CITIZEN needs to reduce its reliance on its comic safety net so we can find that breathing space and connect.

Binge Culture’s Slow Lane, a performance installation dividing the footpath outside Midland Park in two, encourages busy pedestrians to step out of modernity and take a moment in the Slow Lane. The show’s design (by Debbie Fish) is simple and eye-catching: actors in the Slow Lane wear shades of white, a stark contrast to Lambton Quay’s sea of black suits, while Binge Culture advisors (in hi-vis vests) stand by to answer questions from any confused passers-by. Outsiders are also gently invited to participate in the Slow Lane, and I jump in as the slow motion looks relaxing. It’s much harder to hold the slow pace than I anticipated, but the experience is joyfully meditative, requiring a kind of concentration that tunes out the hustle and bustle of everyday life and brings the present moment into sharper focus. Observers can still tap into that meditative quality, too, watching others caught in that concentration. In fact, it’s just as enjoyable watching people grappling with their inner child as they work out whether or not to step in the slow lane themselves, and it’s equally enjoyable watching outsiders attempt and fail to ignore the spectacle entirely.

Man Parts: Dannevirke's Greatest Female Tenor

There should be a Fringe Award that bankrolls a show to tour New Zealand and it should have Carrie Green's Man Parts written all over it. Green brings the house down as Erica Kingi-Little, a teenage girl from Dannevirke who dreams of bringing her tenor-range musical talents to the bright lights of Palmerston North. Erica’s soft- spoken, cute and self-deprecating (like when she pats her tummy fondly as she describes her polycystic ovarian syndrome); conversely, when she sings she’s bold, dynamic and ballsy, irresistible as she belts out well-known Broadway staples from the likes of Oliver! And Oklahoma, all written for tenors. Green is a firecracker, swiftly transforming into dozens of characters and pivoting through settings and musical numbers with incredible proficiency. Phil Loizou’s fast-paced lighting design is just as agile, flawlessly matching Green transition for transition. Green’s crafted a wonderful young female protagonist you want to root for and be friends with, a character who could bring joy to so many others who grew up in New Zealand’s small towns. I hope they get to experience Erica Kingi-Little too.

Matt Loveranes

In an overwhelmingly white Fringe Festival, Samoan 101 added a much needed jolt of diversity to the programme by proudly embracing its heritage. An intriguing exploration of cultural re-discovery, Samoan 101 follows Sonny Va’alele, a young Samoan boy who re-evaluates who he is and the traditional Samoan values he holds when his Caucasian friend Michael falls in love with all things Samoan. The devising team, led by director Sasha Gibb and writer Saufoi Tua Fa’avale, argue with force that cultures flourish when they’re shared and celebrated outside traditional boundaries, but they’re often held back by their simplistic realisation of their ideas. The set-up - Sonny and Michael are assigned to research Samoa as part of a class project - is the kind of contrived premise that would be more at home in an after-school sitcom, the jokes are too often stuck in stereotypes, and the power of the story is dampened by heavy-handed dialogue and an implausible turn of events halfway through. Even so, the ensemble’s infectious energy means that, by the time we get to the show-stopping dances at the end, we’ve had a joyful experience and have a better understanding of Samoan values. The show has charm to spare and is a solid, if unimaginative, entry into the growing canon of shows exploring Samoan issues but the script needs more investment for the show to earn its critical dramatic moments. With the proper guiding hand, Samoan 101 has what it takes to be truly special.

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Gross

There was an epidemic of artists overcommitting this Fringe, but Adam Goodall’s singular effort to produce this “live recording” proves that, sometimes, less can be more. Despite overwhelming critical evidence to the contrary, Goodall pours all his efforts into proving that the schlocky horror Final Destination 3 is in fact the greatest film ever produced. In his corner, a veritable who’s who of the Wellington theatre scene perform his exceptionally researched and unapologetically pop-literate script (including interviews with Final Destination 3’s cast and crew, detailed film analysis and various references to niche podcasts). Goodall plays an increasingly heightened, high-strung version of himself, but director Alice May Connolly keeps him on a tight and exact leash; the result is that this podcast-gone-wrong is significantly more theatrical and visually dynamic than the premise would suggest. In his efforts to get Goodall to just chill out, sound designer Oliver Devlin proves to be a great foil, acting as Goodall’s conscience and wringing the truth about his obsession out of him. Meanwhile, Goodall puts all his insecurities and vulnerabilities on the table, giving his obsession a sober humanity that every person who’s ever held on to an irrational fandom can recognise. Extremely Loud and Incredibly Gross’ willingness to get extremely personal elevates this show and makes it into a true emotional rollercoaster.

Maria Williams embodies queens old and new, real and fictional, official and honorary in a series of monologues written by wunderkinds Uther Dean and Sam Brooks. What could possibly go wrong? A lot, apparently. The first two nights of its modest three-day season were marked by both technical and personal obstacles, but on the third night I witnessed something truly unexpected: theatrical lightning in a bottle. The monologues run the spectrum from irreverent to emotional and are punctuated with conversations between Williams and the audience about her anxieties, personal aspirations and fears of falling short. It’s a great actor’s vehicle, really illustrating her particular set of skills: her accents, her comic instinct, her ability to work a crowd. But it’s these pared down conversations, introduced by Williams and director Ryan Knighton, that make the show truly soar. Williams brings a frankness to her personal monologues that is at times messy, at times unbelievably moving, but always totally honest and magnetic. The monologues vary each night, and in a particularly emotionally-charged moment on the third night, Williams listed the many queens in her life: her mates and relatives, her celebrity heroes, her mum, and a dear friend (“the fiercest Queen she knew, forever and always”). The monologue was a crescendo, building to a moment as profound and sad and truthful as I’ve ever experienced in a theatre.

Ryan Knighton

Thoughts and Observations From My Holiday On Earth

Thoughts and Observations is representative of a lot of shows I saw this Fringe, driven by an interesting idea but falling short of its potential because of its execution and lack of depth. Ray, an enthusiastic alien, comes to earth to film a documentary on humans, but she faces the obstacle of not knowing a lot about humanity beyond a handbook on Earth culture written in the 1980s. Her adventure is at its best when it’s charming: the technical elements, including a highly-choreographed green-screen ‘funding report’, are a real treat, and Hughes cleverly juxtaposes Ray’s total lack of knowledge about our world with a naivete that’s all too familiar. Hughes’ performance goes beyond naivete, though; she touches on the vulnerability Ray hides behind her charm, risking a kind of emotional exposure that’s uncommon in shows like this. Hughes’ script could stand to explore this vulnerability at a deeper level, though, and the pacing creates space for us to drop out of the action. Every scene runs for a similar length of time and the transitions, blackouts as Hughes walks to her next position, are clunky and disrupt the flow. Thoughts and Observations is risky in the way Hughes presents Ray’s vulnerability and embraces, but in only skirting the surface level of the character, it trips up in its translation.

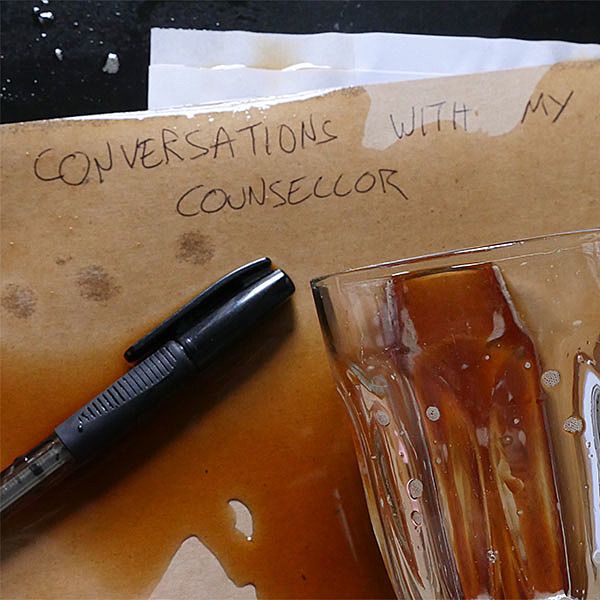

Conversations With My Counsellor

Theatre is a collaborative medium; an absence of collaboration creates insular work that’s hard to read or understand from the outside. Conversations With My Counsellor is an example of work suffering for that absence. An unorthodox psychiatrist (Ian Harris, taking on roles as actor, writer and director) has set up office in Katherine Mansfield House and his newest patient, regular Kiwi lad Mike (Josh Holland) has come to him to fix his drinking problem. There are a lot of interesting set-ups in that synopsis, but Conversations With My Counsellor doesn’t follow through on them: the location, a notable building of historical importance, is superfluous, the psychiatrist’s behaviour is barely investigated, and the show fails to commit to its strongest element - its absurdism. There are moments where Harris’ script goes all in, moments of nonsensical dialogue and warping of the passage of time, and Holland and Harris work well together as a duo, but there’s so much going on that the show ultimately undercuts itself. A show like this, tackling heavy issues like ethical breaches in the mental health system,needs to be clear about what it’s trying to say and commit to that. Conversations With My Counsellor is missing that clarity and that pay-off, and would have benefited from some outside eyes and some focused questions.

I saw Caspar Schjelbred fight an empty room and win. There were about ten people in Fringe Bar’s cavernous 80-seat space on the night I saw Plan C, Shjelbred’s solo, improvised mime show. Without a defined narrative or throughline, the deck was stacked against him - Schjelbred started by asking the audience to call out provocations, to no response. But Schjelbred met the room on its level, responding to its nervous and timid energy. He worked in silence, showing us what he offered, then he asked again, for a single name. This time, he got one, and Schjelbred used it to create a character and a loose story, asking yes or no questions as he went. The resulting performance was so fluid and so in the moment, jumping from one scene to the next every five seconds or so in the most seamless and clever ways. Schjelbred’s form is so slick and practised that you get lost in the action, and his relationship with the audience is respectful and devoid of pressure. I saw Caspar Schjelbred fight an empty room and win, and I have all the time in the world for somebody willing to put in that fight with such craft and such skill.